Feature Interview with Wayne Morrison

December, 2009

(1) What was Toomey’s role in their partnership?

I wish to dispel the common notion that Toomey and Flynn designed and constructed courses together. Toomey was an engineer responsible for overseeing construction crews building courses to Flynn’s specific design plans. All design work was done by William Flynn in an independent design firm. Flynn was a partner of Toomey in a construction business, Toomey and Flynn, Contracting Engineers.

Despite more than 10 years of research and writing a book on William Flynn, I regret to say we do not know very much about Howard Toomey and have never come across so much as a photograph of the man. We know he was 14 years older than Flynn and died in 1933, about 12 years before Flynn. Toomey apparently worked as an engineer for the Merion Cricket Club, though to date no club records have been found to substantiate this. Toomey did not begin working with Flynn in the earliest days of Flynn’s design business in Philadelphia. Flynn worked with a friend of his, Fred Peters. I believe Flynn did the design work and Peters knew agronomy to some degree. Flynn and Peters went into business together selling Basket golf standards sometime in late 1915 or early 1916.

We don’t know when Toomey and Flynn began their partnership but CH Alison proposed a partnership with Flynn and Toomey in 1922, a proposition they turned down. The evidence is overwhelming that Toomey and Flynn were a construction company, predominantly involved in building courses based upon Flynn’s design plans. The firm built the Westchester Biltmore course (now Westchester CC) for Travis and Burning Tree for Alison. Toomey acted as a sort of operations manager, keeping the construction and design firm records. Flynn was able to offer clients a one-stop shop for all their design and construction needs, giving him a competitive advantage over other firms. Toomey and Flynn had a construction crew with very limited turnover, managed by construction foremen William Gordon and Red Lawrence. Dick Wilson was second in charge under either Gordon or Lawrence.

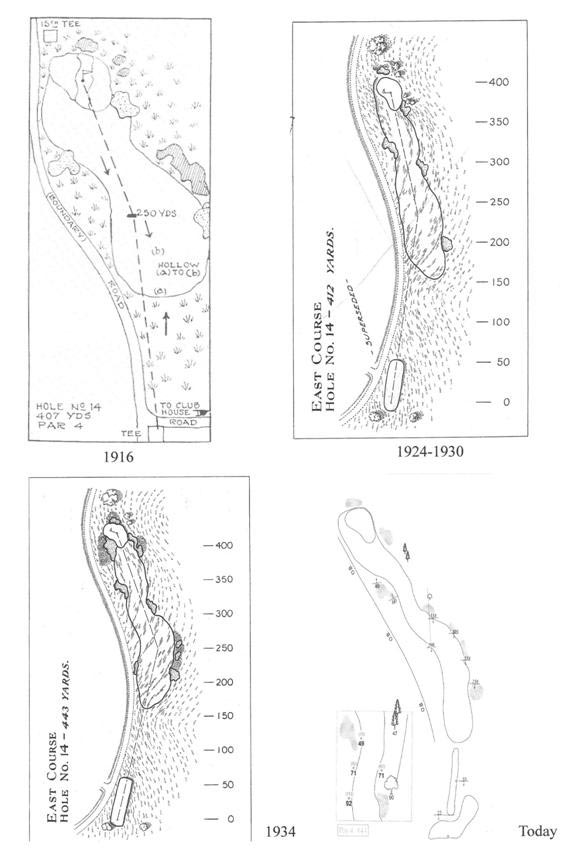

(2) In Flynn’s day, how was the inside of the dogleg fourteenth presented hole on the East Course at Merion?

The 14th hole, despite its proximity to the clubhouse is one of the least photographed of all golf holes on the East Course. The inside of this dogleg is an interesting subject as it has been altered over time.

In the earliest iteration, the tee shot played directly over the old clubhouse entrance road. The left fairway line began near the boundary road, curving away from the out of bounds. The green orientation and left rough indicated the ideal approach angle was to the right side of the fairway. Prior to the 1924 Amateur through the 1930 Amateur, William Flynn redesigned the fairway so as to follow the left boundary line for the entire landing area. The large mound to the right, at 275-300 yards off the tee, was converted to a bunker. Flynn extended the fairway height along the left side of the green. In preparation for the 1934 US Open, Flynn shifted the fairway to the right, adding a fairway bunker on the left and a left greenside bunker flashed into a mound he created. Flynn added some bunkers along the right and redesigned the remaining bunkers. Flynn considered having the first fairway bunker on the left be a carry bunker and kept the fairway along the out of bounds road. This design was not adopted and the hole was redesigned as in the 1934 drawing. The left greenside bunker was removed within the last 10 years as it was not consistent with the 1930 plan though the mound was retained and is kept at fairway height. The left rough now consists of a dense cover of fescues and other long grasses encouraging golfers to play to the right. Long drivers of the ball are tempted to carry the corner of the long grasses for a shorter shot to the difficult green. If the fairway were expanded to the left and a carry bunker returned, that would add an interesting risk-reward temptation for all classes of golfers playing from the correct tees.

The left greenside bunker may be returned at some point prior to the 2013 US Open.

(3) What three courses of Flynn’s no longer exist that would have a materially impact on how he is perceived as an architect?

That’s a great question for any classic era architect, Ran and particularly so of Flynn. Three of Flynn’s very best courses were lost for one reason or another. Dan Wexler did a very nice job discussing some of the lost Flynns in his two books. If you don’t mind, I’ll mention four courses.

I think Boca Raton South was one of the great courses in America, a sort of hybrid course utilizing some of the best principles of Shinnecock Hills and Pine Valley, courses Flynn worked on and was intimately familiar with. Unlike many classic era courses, I believe this course would remain one of the country’s great courses without much lengthening. It was on a site with no more than ten feet of overall elevation change, nearly all of it a gradual slope from west to east, towards the ocean. It is a remarkable study of integrating the prevailing winter wind with the design, triangulation which allows varying effects of the wind, diagonals, shot testing and aesthetic beauty. This was meant to be a championship course, with all holes having a single tee, usually about 20 yards in length. It was heavily bunkered, which was inexpensive due to the site but also required since there wasn’t any existing topography to create interest and strategy. Flynn used the wind, bunkers and fairway lines to influence the line of play to his 55-60 yard wide fairways.

This championship design was varied in its shot demands, had a balanced mixture of long and short holes with resulting half pars and finished with the last three holes into the prevailing winter wind. Whoever held the lead through this finish was certainly in command of his game. Anyone who made up ground over these last few holes certainly earned the victory.

A second course to consider was Mill Road Farm on Albert Lasker’s Lake Forest estate outside of Chicago. The golf course was, from the start, intended to be a demanding course. The fairway widths at Mill Road Farm were generally fifty to sixty yards wide. This afforded ideal angles into the greens depending upon pin position and internal slopes. The course was long, well kept, heavily bunkered and replete with excellent green complexes. It was conceived as an early example of championship golf design playable for players of all skill levels. While golfers had wide landing areas for their tee shots, the better thinking golfers were able to envision the correct lines of play and come up with a proper strategy for scoring. Unlike U.S. Open set ups of today, where angles are reduced along with fairway widths, there was more than one way to play the golf course and it was up to the golfer to figure out the best way under the conditions of the day and their own game. Today’s championship courses all too often have the fairways narrowed to 22-yards with decision making factored out of play resulting in the only test of golf being the physical execution of a singular tee shot demand to a fairway less than half as wide as intended on the classic courses. In promoting the protection of par, the set ups we see today eliminate the judgment demands of golfers and dictate play. Not so with the Flynn design for Albert Lasker. The length and variety of shot demands called for a high level of execution while the width and angles incorporated in the design demanded smart decision making.

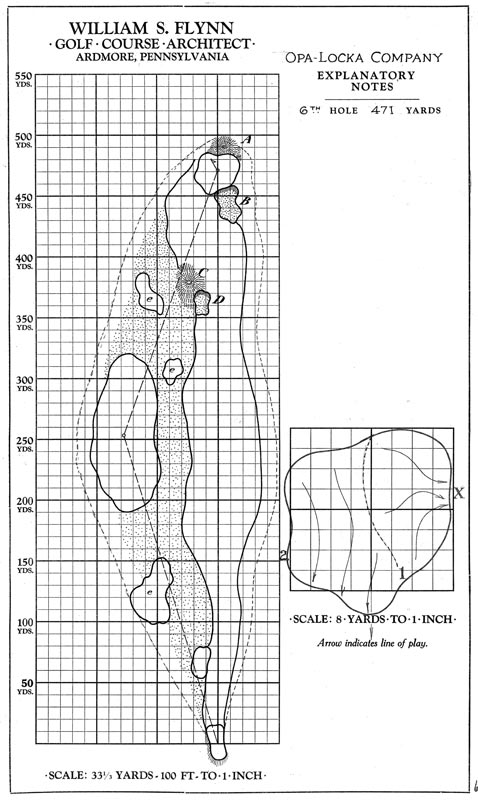

Flynn designed a course for Glenn Curtis, of motorcycle and aircraft fame. Curtis was developing a new city in Florida and chose Flynn to design his course. Near the current site of Miami’s airport on flat ground, Flynn utilized man-made canals, sandy waste areas and island fairways to create a fascinating golf course routed in such a way so as to offer a variety of wind effects. The sixth hole shown above is an example of how Flynn took a familiar concept, the Channel Hole based upon a concept originally found at Littlestone GC in Kent, England. Macdonald’s version at The Lido Club was a par 5. Flynn designed a long downwind par 4 with the best approach angle to the green from an alternate fairway amidst a sandy waste area. Those golfers who wished to play safe up the primary fairway were left with a difficult approach shot over a large bunker, especially to a pin on the right half of the green. Is the concept better suited for a long par 4 rather than a par 5? Perhaps so, especially over time as Flynn saw clearly the effect of technology and stronger golfers.

As a fourth example, I wanted to mention the second course Flynn designed for Eagles Mere Golf Club in Eagles Mere, PA. While in truth, Flynn only completed the front nine as the second nine holes were cleared but never completed due to financial problems. Routed roughly in the shape of an “L,” as with Merion East, the course was designed with only twenty-seven bunkers. Flynn’s philosophy was only to use man-made hazards when necessary. With the dynamic natural topography on the site of the new course at Eagles Mere, there was little need for bunkers, Flynn designed around the natural landforms and use these as determinants for strategic decision-making. The land featured a total elevation change of an astounding 280 feet. Flynn designed individual holes with a rise of 130 feet from tee to green and others with a fall of up to 180 feet! Flynn boldly routed up and down slopes, across slopes with canted fairways, around an open marsh and in ways that maximized the variations in the effect of wind. Flynn designed his customary 60-yard wide fairways so that balls had room to maneuver and allowed gravity to influence the outcome of shots. Specific shot demands, even amid such wide playing corridors, were tested in this manner. At times a draw into a slope was required to hold the shot in the fairway. The green designs and limited greenside bunkering added to the shot demands. While there was meant to be a freedom of play with the limited hazards, careful study or repeated play would slowly reveal the ideal landing areas and approach angles.

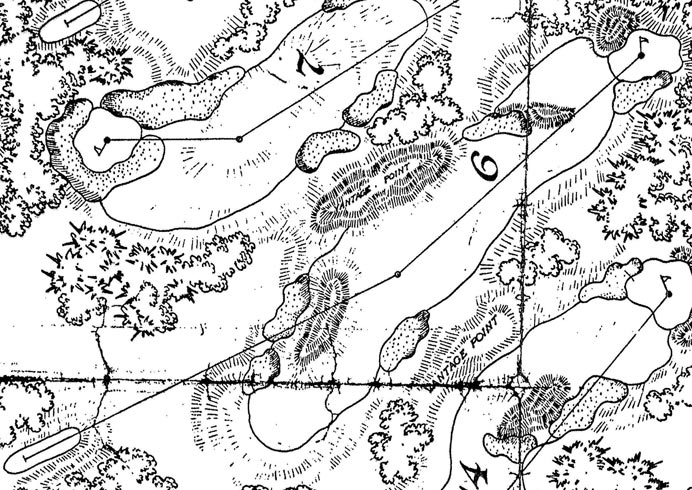

Given the lack of recognition of Flynn, there are a great many holes which deserve more study. However, I overstepped your limitation on the last question, so I’ll stick to three holes as you request. The sixth at Indian Creek is a remarkable design, rarely seen due to the exclusivity of the club and its location on an island in the Bay of Biscayne.

Indian Creek CC, 6th hole

Flynn Course: 430 yards, par 4

1930s: 444 yards, par 4

Today: 445 yards, par 4

This hole is one of the greatest examples of visual deception in golf and also of strategic bunkering. The preliminary plan seen in the above routing map was refined by Flynn prior to construction. Flynn designed the bunker plan so that the four fairway bunkers seemed to meld with the three diagonal bunkers near the green end so as to completely obscure the landing area. The temptation is to hit to the right side of the fairway where it seems there is open ground but this is the least favorable position from which to approach the green.

Standing on the tee, you don’t see any landing area over the field of what appears to be seven bunkers on the left. In fact there are only four bunkers in the fairway complex. The other three bunkers are on a diagonal short left to greenside. However, they look to be one giant bunker field with no landing area beyond. Yet there is a 200-yard gap between the fairway bunker complex and the first of the three diagonal bunkers. In addition, there is about a fifty-yard difference between the middle diagonal bunker and the right green side bunker.

Flynn took the design one step further by integrating the visual deception with ground contours which affect decision-making, creating a visual dynamic impacting strategic decision making. If the golfer takes the tee shot directly over the center of the bunker field he or she is rewarded with a turbo boost that kicks the ball towards the green leaving a shorter shot into a slightly elevated green. If you take what appears to be the only landing area or safe area away from the bunkers, the ball kicks right reducing the roll and leaving an approach which requires carrying the last diagonal bunker on the right. This bunker has another deception. The top line is configured in a way that makes it appear to be perpendicular to the line of play from the right side of the fairway when in fact it is on a diagonal and you need a full club or two to carry the right side of the bunker onto the green.

The boldest line, over the center of the fairway bunker complex leads to the optimum approach position. The longer driver is rewarded with a turbo-boost off the backside of a ridge that yields a significantly shorter shot into an elevated green. A tee shot that takes a less aggressive line along the right side of the bunkers or is sliced or faded will be propelled sharply to the right with little forward progress and a decidedly more difficult angle of approach.

The left and middle bunkers short of the green look to be directly in line with the right greenside bunker, when in fact they are sixty-yards short of the right bunker. The middle bunker was originally drawn as a mound but appears as a bunker in early aerial photographs. This outstanding hole uses similar perception devices as the former fourteenth at Manor Country Club prior to its recent remodeling.

Rolling Green, 3rd hole

This hole, like the fourth at the Cascades, is a downhill par three. If the slope of the downhill is slightly reduced on the green compared to its surrounds, it appears that the green slopes back to front when in fact it follows, to a lesser degree, the overall slope of the ground around the hole and slopes deceptively front to back. Flynn enhanced the back to front false perspective by constructing the top lines of the bunkers so that they slope from back to front. In the case of this drawing, it would appear by the flow lines on the green detail that this is an early version and not the final green construction. Other greens with similar misreads include the eighth at Merion East and the fourth at Cascades.

The human brain can be fooled. Flynn understood how to do that and utilized perceptual miscues to unsettle a golfer and identify who is in most control of their game. At the same time, Flynn balanced executing the shot with correctly understanding the situation and creating the correct strategic plan. Flynn manipulated the top lines of bunkers to make them appear perpendicular to the line of play, when in fact they are on a diagonal and one end of the bunker requires a carry of one to two more clubs than the other.

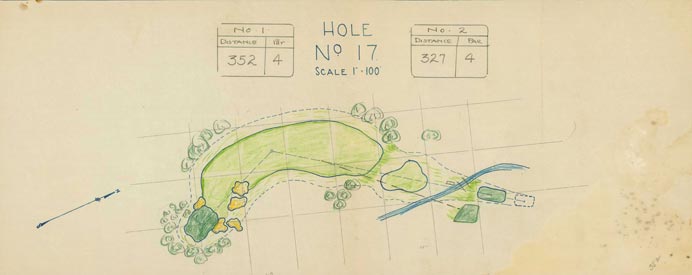

The Country Club, Pepper Pike Ohio, 17th hole

Like many Flynn courses in the geographical regions he worked, The Country Club in Pepper Pike, Ohio is a very private club which, until recently, shied away from recognition. This may change as the club enters the public stage in 2012 when it is scheduled to hold the US Women’s Amateur.

This is considered one of Flynn’s finest short par 4 holes. The dogleg fairway creates angles of play to be considered along the right and left fairway lines. Club selection is pivotal so as not to drive through the fairway. The right to left fairway slope drops steeply towards the bunkers short of the green and then rises up to the green site benched into the hill.

Flynn revised the bunker scheme short of the green in pencil on the routing map and deleted a right fairway bunker. The fairway bunker was beyond the landing zone and was intended as a line of sight bunker. Flynn chose to remove the bunker resulting in a much less defined target for the tee shot. The final design iteration added a third tee to the left of the initial tee design.

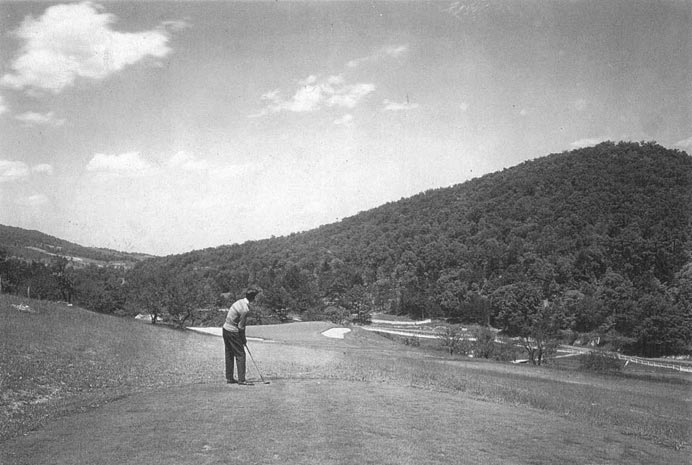

(5) Flynn spent numerous summers at The Homestead Resort. Just how good was The Cascades at its peak? What three things most need to be done there now?

To be clear, Tom Paul and I wrote the long range restoration and master plan for Club Corporation, then the owners of The Cascades. Much of the plan was implemented, which was restorative in nature, using the original Flynn drawings and old and new aerial and ground photographs. Craig Disher helped out tremendously as we determined what was planned, what was built and what was done to deviate from the original design intent. There is another ownership group in control of the resort and we haven’t established a relationship as yet. So I don’t know what their thoughts are for doing additional work. I can tell you what we’d like to see.

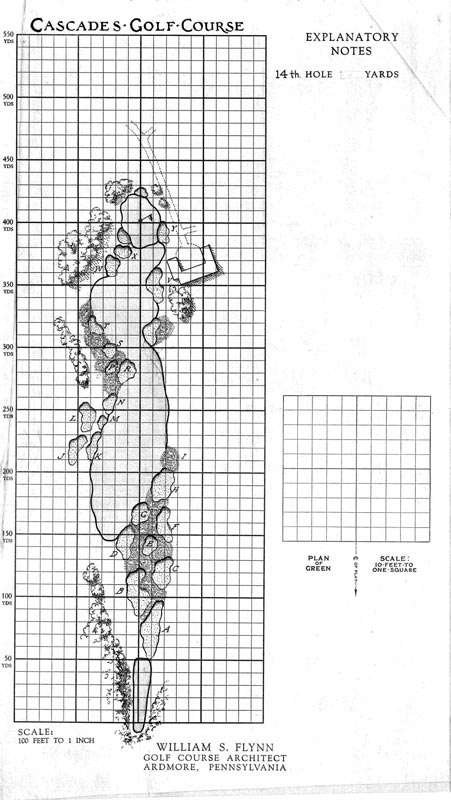

Rather than moving the tee back on the fourteenth hole, Robert Trent Jones moved the green down the line of play. So much so that he compromised the tee shot on the long par three fifteenth hole. This resulted in both holes being compromised and lessened in value. I would put in a new back tee and restore the green to its original location and design. The current green looks nothing like the other greens on the course.

With the restored green position, I would add the bunker scheme Flynn intended to be constructed as above. The land is flat and featureless so the bunker scheme would create interest and added strategy.

I would then return the proper playing angle to the fifteenth hole by restoring the obsolete tee. Some tee angles can change significantly and not change the way the hole plays too much. Some tees can be moved a few paces and the results change dramatically for the worse. Well, the fifteenth tee was moved fifty yards to the right, imperiling golfers on the first tee and approaching a medium size green from a bad angle on the 252 yard par three.

I believe the course would benefit from restoring the stream fronting the fifth hole, which was subsequently covered long after Flynn passed away. The stream would look great and probably help with flooding issues in the area as the culvert is too small to handle excess rains and snow melt. Lastly, I would do some tree clearing which not only exposes grand vistas, but also highlights Flynn’s ability to not only tie in architectural features to local surrounds so they look natural, but also to distant features such as mountains some miles away. Flynn did this on a number of holes such as the eighth where the right to left slope of the green is reminiscent of the slope of the mountain in the distance.

(6) What did Flynn do at Pine Valley and the Country Club outside of Boston?

As at Merion East, where Flynn did a considerable amount of design and construction, he was involved in a great deal more design and construction work than is commonly thought at The Country Club in Brookline and to a lesser degree at Pine Valley. These courses are covered in the 5-volume (2047 page) set comprising The Nature Faker, William S. Flynn, Golf Architect. Let’s leave a bit of mystery for the moment. Suffice it to say; when Flynn completed his work at The Country Club in Brookline, MA, a majority of the golf course was Flynn, though most of the existing holes were played in the original corridors. We know about Flynn’s involvement on holes two and eighteen at Pine Valley. Tom Paul is the leading expert on the architectural history of Pine Valley and he and I believe Flynn was involved in work on holes twelve through fifteen and seventeen. Additional research needs to be done. Joe Bausch is doing more than his fair share.

(7) What are some of the more prescient articles that Flynn wrote?

William Flynn wrote a series of articles, the first in 1923, for the USGA Green Section. Flynn was one of America’s experts on agronomy and turf grasses for golf. Flynn and Hugh Wilson were instrumental in the study of new grass strains, grow-in techniques and maintenance.

His 1927 articles covered a wide range of topics. The articles leave no doubt that Flynn understood technology impacts on the sport. He was a fine player who grew up playing the gutta ball with hickory shafted clubs and witnessed firsthand the impact of the Haskell ball and steel shafts. Unlike a number of his competitors, Flynn recognized the need to design in elasticity in his golf courses, which is one reason why his courses have stood the test of time for all classes of players better than most designers of his era.

Here’s what Flynn wrote about combating increasing distance attained by players of his era and his understanding of designing for the future:

‘Again the question of the ball has a great bearing a what type a certain length hole will be. Time was, and not so many years ago, when a hole 400 yards long on average ground was a good two-shot hole for the star players; now, the same hole is perhaps a drive and spade for the better class golfers.

In view of this the architect of today plans his full two-shot holes from 440-500 yards, depending on the character of the land and if the distance to be obtained with the ball continues to increase it will be necessary to increase the length of all holes on golf courses accordingly if the same standards of play are to be maintained.

All architects will be a lot more comfortable when the powers that be in golf finally solve the ball problem. A great deal of experimentation is now going on and it is to be hope that before long a solution will be found to control the distance of the elusive pill.

If, as in the past, the distance to be gotten with the ball continues to increase, it will be necessary to go to 7500 and even 8000 yard courses and more yards mean more acres to buy, more course to construct, warfare way to maintain and more money for the golfer to fork out.”

“America has developed a more or less stereotyped shot to the green that is the high all carry shot. This has been brought about no doubt by the fact that fairways and particularly approaches have gone unwatered during the summer when the ground has become hard. It is much simpler to play a high carry shot to a soft green which gets water than to attempt a pitch and run to a green with a cement like approach.

In the first case when all greens are watered a constant condition prevails but in the case of the approach the ball hits and is liable to bounce anywhere.

In order to cultivate the pitch and run, the run-up shot and the long iron or wood with run it is necessary to present a suitable playing condition on the approach and this can best be brought about by the architect insisting on a water system for fairways and by the greenkeeper making generous use of it.

Natural topographical features should always be developed in presenting problems in the play. As a matter of fact such features are much more to be desired than manmade tests for they are generally much more attractive.”

Flynn suggested that courses without enough elasticity or a budget to implement course lengthening could water the landing areas of tee shots so that the ball would not have much roll thus allowing the golf course to play longer than its yardage.

(8) Are there any misconceptions about Flynn that you would like to set straight?

As I stated earlier, to set straight that Toomey and Flynn were not design partners. Howard C. Toomey never designed a golf course, save for assisting in drainage plans. Flynn was the only architect involved in golf design. Toomey was a partner in the construction business while Flynn was the only member in his design firm. While Red Lawrence, William Gordon and Dick Wilson went on to become accomplished architects, like Toomey, they did no design work during their employment by Toomey and Flynn.

The only remnant of the Macdonald design/redesign for Shinnecock Hills is the seventh tee. There is nothing else left of Macdonald in Flynn’s complete redesign and design work. Any written representations to the contrary are incorrect and were made without the benefit of sufficient inspection of club documents and the Flynn design drawings, many of which the club had in their possession and others which have come to light at a later date. The Macdonald tee outlasted the Flynn tee, if it was ever built. Perhaps at the mowing height and green speeds of that era, the Flynn tee wasn’t deemed necessary. However, Flynn was right in wanting it built as increasing green speeds make such a tee an absolute necessity under firm and fast conditions, especially with certain wind patterns. Try teeing it up from several paces to the left of the Macdonald tee, it makes a huge difference. Your hosts may look at you funny, but it is a wonder that a few paces to the left can make such a difference.

Misattributions plague the Flynn legacy. Some were fostered by his employees (Lawrence at Indian Creek and Wilson at Shinnecock Hills). We now know Flynn designed Kittansett Club, not Frederick Hood and Norfolk Country Club, not Donald Ross. Most of Pocono Manor’s East Course is Flynn

Flynn did not design Philmont North, it is evident that Willie Park, Jr. designed the course. Whether the club ever comes to grips with that attribution is another matter as they cling tightly to their Flynn attribution. Too bad they don’t recognize the revolutionary role Park played in golf architecture as well as the brilliant designs he left for us to enjoy. There are so few Park courses in Pennsylvania, I hope the club eventually embraces the attribution.

(9) What sort of things should we consider about Flynn that we probably don’t already know?

Flynn’s broad and deep expertise in all phases of golf design and construction and maintenance practices were unmatched by any other architect of his era. This expertise enabled him to have considerable competitive advantages over other classic era architects. He was able to provide accurate cost estimates for green, fairway and bunker construction so that clients were not surprised by the overall cost for design and build. Flynn’s believed in using additional fill to create natural lines but felt that the additional upfront costs would be more than offset by continual maintenance savings. He was one of America’s first great superintendents and his experience in that capacity forged a design style that made his courses cheaper to maintain in the long run and sustainable.

Flynn designed accurately on paper. His drawings were exactly to scale. Often he made numerous iterations on paper rather than on the ground. His extensive time on site and design process saved money and resulted in a quality product.

Flynn was the finest router of golf courses, electing to use bold lines of play into and across topographic features. He was not at all systematic in his approach to routing such as Donald Ross. He did not look for areas to locate specific hole concepts and thus compromise other routing possibilities.

Flynn used perceptual tricks better than any other architect, which throws all classes of golfers a bit off, exposing the best thinkers as well as strikers.

If Flynn’s plans for Denver Country Club’s redesign were followed to the full extent, Cherry Hills would not have the notoriety and championship heritage it has today.

Flynn’s designs for estate courses, such as made for Ned McLean in Washington, DC, John D. Rockefeller in Tarrytown, NY and Robert Cassatt (Mary’s brother) in Bryn Mawr, PA were astonishingly innovative with double greens, reversibility and fascinating features you can design on limited play courses.

(10) What are your thoughts on Flynn’s work at Lancaster Country Club, host of the 2013 Women’s Open?

I am very pleased Lancaster is holding the 2013 Women’s Open. Lancaster and The Country Club in Pepper Pike are two courses in Flynn’s portfolio that will benefit from exposure inherent in holding a significant USGA event. Now if we can only get Huntingdon Valley to hold one. Anyway, back to Lancaster. It is a showcase for the merits of having an outstanding golf course architect be a lifelong consultant. Flynn’s course opened in 1920 and he constantly tinkered with it for the remaining 25 years of his life. During that time Mother Nature tinkered with the site as well given the severe flooding that happens once every decade or so.

Ran wrote a tremendous write up of the course in his Courses by Country section. As with his other essays, he captures the spirit and nuances of clubs and courses as well as anyone ever has, especially on a single visit. I share all his well-crafted opinions of Lancaster Country Club. I think it is one of Flynn’s very best original designs and therefore one of the best designs in the country. Along with Huntingdon Valley, it is at the top of the second tier of Flynn courses which reside beneath the extraordinary Shinnecock Hills golf course.

The collection of par fours at Lancaster include, according to golf writer Jim Finegan, one of the best sets of long par fours in the world of golf. I found through my travels that it is easy to design difficult golf courses and far more challenging to design interesting championship designs. Flynn designs enjoyable difficulty and accomplishes it with a variety of shot tests, varied stances and combinations of line of play and distance requirements. You don’t see long, straight, flat fairways with bunkers down either side ending at heavily contoured greens with deep flanking green side bunkers at the opening. What Flynn offers at Lancaster is a collection of golf holes which utilize the natural features of a golf course and any earth moving is tied in to the natural surrounds in such a way as to hide the hand of man.

Flynn was constantly improving the golf course and his holes across the river (3-5) are among the finest on the course. While not redesigned by Flynn, holes 2 and 16 were dramatically improved and also are among the best at Lancaster. The long relationship between Flynn and Lancaster gave rise to a course worthy of study by discerning students of the game. It can be set up for enjoyable member play and the finest golfers in the world. Isn’t that all a golf course can strive to be? Lancaster is an enjoyable challenge for all classes of golfers and thus a testament to Flynn’s outstanding routing and design skills.

(11) Please describe three of his all-time best putting surfaces.

You seem to be fixated on three examples. Wow, this is a tough one. Flynn’s greens were designed to be interplays of long slopes, generally not severe contours. These make the greens hard to read, especially on mottled surfaces which existed in his day and courses today that hold fast to an older look, such as Merion East and West. He didn’t utilize template greens or geometric features like horseshoes or other recognizable contours. Can you tell I don’t like template hole designs? Yet his slopes created greens within greens and areas where you simply should not be depending upon pin positions, they simply were not so overtly presented as are significant internal contours. It is hard to put into words and is best left to experience, but for some reasons (visual deception, grain, etc.) his greens are hard to read and make putts on, even with a lot of play.

As an accomplished player and very long driver of the ball, Flynn put into practice design features which tend to throw players off their game. He came to an understanding of psychology and perception to deceive players and to make the greens appear simple but putt hard. This weighs on players’ minds as their expectations are rarely met and weaker players tend to get frustrated. The better thinkers understand the measure of difficulty and can manage their expectations to a higher degree.

Flynn believed in adapting greens as much as possible to the specifics of the site and sought to avoid repetition. This approach results in a wide variety of green designs. He wrote in September 1927,

“There has been in the past considerable copying in the designs of greens. The custom has been to select so-called famous holes from abroad and attempt to adapt them to a particular hole. While it is a simple matter to copy a design it is almost impossible to turn out a green that resembles the original. This is not due to any technical reason but is on account of the surroundings being different from the original.

Copying greens in detail is not generally a good plan but there should be no hesitation about copying the principal connected with any green particularly when it is good.

It has often been said that architects have designs for 18 greens and that the same ones are used over and over again on the various layouts.

A successful architect today does not follow that system. His greens are born on the ground and made to fit each particular hole.

In constantly designing greens it is very easy for an architect to acquire a pet type and to apply this frequently, thus creating greens of great similarity. A tremendous amount of study must be given each site on the ground and also on paper so as to get distinctive types, thus avoiding sameness.”

Flynn greens take a long time to figure out, especially as he had a bag of subtle tricks which made reading his greens a real test of thinking as well as executing.

Rolling Green 1st

The opening hole on Flynn’s championship design for Rolling Green is a relatively short hole with an easy enough tee shot. The complexity of the slopes makes this a very difficult green, let alone an opening green. There are plenty of three putts and more on this green, which makes stepping up to the second tee and its daunting tee shot a nerve wracking beginning.

Be wary of back left to front right putts! Flynn’s initial design, probably not implemented was for the fairway to end thirty yards or so in front of the green, promoting an aerial shot to an island green. The left greenside bunkers have recently been combined to the original one large bunker design by Forse and Nagle.

Shinnecock Hills 5th

Tom Paul and I have been working with the club for several years now to implement a restoration plan. It is going very well and about to pick up pace. For those of you that are playing again there this year, please take note of the lowered tee on eleven. We restored it to its original lower level, which should please Pat Mucci and others who appreciate the perplexities which result from skyline greens.

Most of the greens have dramatically shrunk and we are seeing the benefits of restoring green space because of the accompanying pin positions which are recovered. At Shinnecock Hills, restored pin positions tucked behind bunkers and close to falloffs require more precise shot placement off the tee and controlled distance and trajectory for approach shots. One of our favorite expansions will be on the fifth green, which originally played as the fourteenth before the nines were switched. We will recover pin positions at the front right corner of the green, behind the right green side bunker and up to the rear falloff.

While this isn’t one of the great greens in a portfolio of superlative greens by a master architect, it is a wonderful green site with the most severe slope I’ve ever seen on a green. It is a daunting tee shot straight uphill with the Rockefeller family playhouse as a backdrop. It is easy to miss this tiny green with its trio of bunkers fronting the green capturing any short shots. Chipping to and putting on this green is so much fun. A golfer cannot hope to make many good chips or hole many putts, so the often absurd results evoke laughter and a sense of joy rarely found in a round of golf. This family course has long been a focal point for family gatherings and much fun over the past 80 years.

(12) Flynn was an admirer of the big one shot hole. Please describe three of his best.

In my mind, Harry Colt and William Flynn were the greatest designers of par three holes by a pretty wide margin. Their overall body of work is simply better than anybody else. Flynn’s collection of par threes on courses such as Shinnecock Hills, Rolling Green, Philadelphia Country, Kittansett, Cascades, Indian Creek, Lancaster, Lehigh, Manufacturers, really nearly all of them are just so good. I don’t know anyone other than Colt (I’ve seen a lot less Colt than I have of Flynn) who comes close to the number of great par threes. Flynn’s par threes are in harmony with the surrounds which lends a great deal of variety and uniqueness to them. While he had a couple of his own versions of a Redan hole greens (7th at Shinnecock Hills, 7th at Philadelphia Country Club, 3rd at Huntingdon Valley, the original 5th at Springdale and the 14th at The Country Club in Pepper Pike), for the most part, the holes were unique and strong. Flynn created quality short and medium par three holes. But you’re right, Flynn seemed to enjoy providing long par threes on nearly every course, certainly a hallmark on all championship courses, as he wanted to shot test accuracy with a driver on a par three. Before the excessive irrigation of golf courses post WW II the ground generally played firm and fast through the green. Low draws that could run considerable distances made such shots possible in the days of the Haskell ball, hickory shafts and wooden heads. I would like to illustrate this point with four examples (sorry). Flynn designed other notable long par threes including the fifteenth at Cascades, 245, yards; the seventh at Lehigh Country Club, 233 yards; the thirteenth at Mill Road Farm, 240 yards; the thirteenth at Manufacturers Country Club, 233 yards; the fifteenth at Cascades, 245 yards and more.

Rolling Green, 10th

The last of the three difficult mid-round holes is the uphill par three tenth hole. Flynn drew the hole on the preliminary plan as 260-yards. This shot demand hole necessitated hitting a low running hook allowing the natural topography to feed the ball onto the green. The hole was constructed as a 243-yard par three from the middle of the back tee but a recent restoration and modernization by Forse Design established a back tee according to Flynn’s plan.

Philadelphia Country Club, 15th

Flynn’s tendency to design long par three holes is evident in this famous hole. Uphill all of 223 yards when first constructed, the top of the flag is hardly visible from the tee. It is alleged to have been aced only twice in its existence. The green is very demanding with a subtle central spine which yields a lot of head scratching after some putts.

Both sets of tees were lengthened with a wider range of yardages allowed including an additional eleven yards added to the back tee. The bunker scheme was basically intact with minor revisions. The green outline was altered slightly in preparation for the 1939 US Open.

Kittansett, 11th: 241 yards

The eleventh hole is the longest par three on the course. The green is situated on the far side of a cross bunker and features two-tiers with a steep slope from top left to bottom right flanked by deep bunkers. The hole today is played at 241 yards, eleven yards longer than opening day.

Shinnecock Hills, 2nd

Flynn constructed a tee on this long par three to the left of his new first green near the property boundary. This green site was once the finish of the Macdonald par five twelfth hole, “Long.” The angle of approach was right of the current tee. Flynn’s plan called for the removal of all the fairway bunkers on the original hole. In fact, Flynn filled in one of the original Macdonald cross bunkers and left the remaining bunkers for a time. There are no remnants of the original fairway bunkers. Flynn redesigned the green in the original location to accept a long approach from the new angle of play. The square green outline was replaced with a more complex outline. The preliminary plan called for a green oriented along the line of play. Flynn’s final plan called for the green to be offset from left to right.

As can be seen in the above hole drawing, the hole was designed within the concept of a par three with an “S-curve†such as employed at Indian Creek and Boca Raton South. With the prevailing winter wind blowing left to right, the tee shot would have to be played over the bunker field to the left of the green or with a draw into the wind to hold the green. There is also an opening to the green, which allows an optional shot type, a low running shot over the second bunker on the left feeding onto the green. The hole plays 221 yards uphill. We proposed lengthening the hole up to 280 yards with a new rear tee slightly up a slope behind the current back tee.

(13) Flynn was an all-time master at creating interesting playing angles with Shinnecock Hills as a prime example. Did his initial designs feature such interesting angles or did this talent evolve slowly over his career?

Flynn’s outdoor classrooms at Merion and Pine Valley provided outstanding opportunities to learn and clearly influenced Flynn a great deal. Subsequently Flynn would have a great deal of influence at Merion and to a far lesser degree, at Pine Valley. It was at these two courses where Flynn learned to design with a comprehensive repertoire of shot testing and a balance of aerial and ground approach demands, a feature found on many of his later courses.

I think Flynn had a genius for routing golf courses and displayed that talent from the start, particularly in achieving his results utilizing natural features specific to each site. Unless someone has attempted to route a course or followed closely those that do it well, it is difficult to imagine what is required and the mixed variety of results one can achieve.

While drawings of his earliest solo designs (Kilkare, Doylestown and Harrisburg) do not exist, we have some idea of his early efforts. He used offset fairways and greens to a far greater degree than many other classic era architects. These offsets require both line and distance demands that straight fairways and approach angles fail to provide. Later on his designs, starting in the early to mid-1920’s, Flynn began to combine falloffs and short grass collection areas around greens and bunkers which accentuated the need to think your way around the course and to play to particular areas of the fairways and greens to increase the possibility of the best score.

Early on, Flynn showed a preference for uneven fairways and the precise shot making required to hit off less than ideal lies, even in the fairway. Later in the 1920’s, Flynn upped the shot making requirements at places like Huntingdon Valley Country Club where the ideal shot might call for a draw off a fade lie and fades off draw lies. Certainly in tournament play the better player even in a single day event was likely to be identified as the precision level for shots reduces the impact of luck in the outcome.

His raised bunkers, particularly interceding between landing areas and greens, foreshortened the apparent distance behind the bunkers. He used changes in elevation to reduce perceived distances. I think the eighteenth fairway at Merion East was a good teaching tool for his subsequent use of that feature.

Later in his design career, Flynn utilized perceptual miscues more and more such as those found at Indian Creek in Miami Florida. He manipulated the top lines of bunkers to make them seem perpendicular to the line of play when in fact they followed a diagonal.

He seemed to prefer long and difficult finishing holes, such as planned for Eagles Mere (453), Huntingdon Valley (415 uphill), Kittansett (445), Yorktown River Course (431). Though Flynn wasn’t opposed to finishing his courses in atypical ways such as the par 3 finishing holes at the Cascades and Doylestown Country Club.

Flynn’s drawing style improved significantly from his earliest design drawing we have (Lancaster, 1920). His preliminary plans for Shinnecock Hills are expertly drawn.

(14) What was Flynn’s tree plan for Shinnecock Hills?

This is CH Alison’s review of William Flynn’s tree plan:

“Planting:

On the low land it is the intention to place high growth on the higher portions, and low growth on the lower portions, and to produce in this manner an illusion that the ground is undulating. This is entirely practicable. It is also the intention to have clumps rather than lanes. Both these things will give good results not only as seen from the holes themselves, but also from the Club House. It is very desirable that your landscape man should understand how important it is that he should work with Mr. Flynn, and not independently.”

There is no evidence that this intriguing planting process was implemented, perhaps as a result of the economic impact of the Depression. The impression of greater undulation inherent in this proposal is important whether or not it was developed and merits consideration by modern golf course architects and landscape architects.

(15) Please come up with your Pat Ward-Thomas eclectic eighteen holes but using only Flynn holes.

1. Merion East: 350 yards, par 4

2. Rolling Green: 445 yards, par 4

3. Philadelphia Country: 585 yards, par 5

4. Lancaster CC: 396 yards, par 4

5. Opa Locka GC: 229 yards, par 3

6. Indian Creek CC: 445 yards, par 4

7. Yorktown CC River Course (NLE): 430 yards, par 4

8. Kittansett Club: 209 yards, par 3

9. Huntingdon Valley: 460 yards, par 4

10. Boca Raton South: 399 yards, par 4

11. Shinnecock Hills: 158 yards, par 3

12. Shinnecock Hills: 468 yards, par 4

13. Boca Raton South (NLE): 467 yards, par 5

14. Shinnecock Hills: 448 yards, par 4

15. Philadelphia Country: 223 yards, par 3

16. Shinnecock Hills: 540 yards, par 5

17. The Country Club, Pepper Pike: 387 yards, par 4

18. Kittansett 460 yards, par 4 and Lancaster CC: 446 yards, par 4

7099 or 7085 yards, depending upon the ultimate hole with an original par of 71, though today the 13th would play as a par 4. That works since Flynn knew a few great par 70 courses with two par 5s.

This was a very difficult assignment as Flynn’s courses were nearly all very strong indeed and he didn’t design very many (55) compared to his contemporaries, preferring to taking on fewer projects while spending considerably more time on each site. Does any other architect from the classic era (or any era) have a superior collection of eighteen holes?

(16) Please speak as to Flynn’s background in greenkeeping and turf grass experiments where he added nearly as much as he did to the profession of golf course architecture.

Flynn’s interest in the natural world, especially fauna, was pronounced at an early age. He taught himself enough scientific and practical knowledge that he was accepted into an inner circle of turf experts fostered by the efforts of Charles Vancouver Piper and Russell A. Oakley of the United States Department of Agriculture. Other early turf researchers included Hugh Wilson, Edwin J. Marshall, Lyman Carrier and Walter C. Harban. These men conducted turf experiments on plots in Philadelphia and Washington, D.C. and their findings advanced the understanding of planting and maintaining turf for golf courses, stadiums, airports and public parks. Together they established the National Green Section, which was later absorbed into the United States Golf Association as the USGA Green Section. Much of our understanding of these early years is a result of the study of the massive collection of letters and papers housed in the USGA Green Section files between Hugh and Alan Wilson with Piper and Oakley. These men corresponded almost daily for nearly fifteen years during the development of the two courses for the Merion Cricket Club, Pine Valley and a host of other important courses. The information in these letters reveals the rudimentary state of agronomics at the time and the rapid increase of experimentation with the results directly applicable to turf management.

These men forged an understanding of the relationships between plants, geography and economics leading to practical uses on golf courses nationwide. Colt and others from Europe contacted these men for advice and solutions to a host of problems that we have a difficult time imagining from our perspective eighty or so years later.

The USGA Green Section began publishing a monthly record of reports and articles of interest to superintendents and green chairman starting in 1921 and is still assisting the cause of good turf for golf and other recreational facilities. Flynn’s series of articles, the first in 1923 and the remainder in 1927, were instrumental in guiding clubs and architects in the process of selecting a site, selecting an architect, design and construction.

Flynn was the superintendent at Merion for five years during which time he worked closely with Hugh Wilson in the on the job training both men needed to manage the turf for a golf course. In June of 1911 a man with twenty years experience in America was hired to work as green keeper. Perhaps Flynn took over the position after completing the construction of the West Course. Flynn left Merion for a time in 1918 to work at Bethlehem Steel as part of his war commitment. Flynn got a deferment from active duty as he had a wife and child. During his absence, Joe Valentine, Flynn’s assistant took over the management of the two golf courses. Flynn trained Joe Valentine, once a seminary student in Italy, who would go on to be, like Flynn, one of the great early superintendents in America.

During World War II, Flynn experimented with a crop of soybeans. Connie Lagerman recalls her father saying that one day soy beans would feed the world.

(17) How did Flynn get the Rockefeller job at Pocantico Hills in 1937 when work was slow and every architect was keen for the project?

The project to design and build the Rockefeller family course was one of a few projects available to architects in that era, and a number of architects openly sought the job or were under consideration. The Rockefeller family archives contain a massive amount of material documenting the storied history of the family. Because the records are so detailed, the authors were able to document many of the details related to the hiring process and the design and build processes of the new golf course John D. Rockefeller, Jr. determined to build for his father. This unusual insight into the project development offers the reader a glimpse behind the family veil and also into William Flynn’s character and methods of operation.

In 1934, John D. Rockefeller, Jr. with the help of his sons John III, Nelson, and Laurance, oversaw the planning of a new modern course for the estate. It was several years before an architect was selected and the project completed. Unfortunately, Mr. Rockefeller, Sr. would not live to see the finished course as he passed away in 1937 at the age of 98.

In April 1934, Major Jones wrote to Mr. John R. Todd, the President of Todd, Robertson and Todd Engineering Corporation, the engineering firm engaged to propose a plan for the family golf course. Jones stated,

“The only man in this field in whom I have any confidence is Perry Maxwell. He has had a lot of experience and I know he has kept pace with the research work of recent years…â€

Mr. Todd recommended to the Rockefeller family that Maxwell be hired to design the course and Major Jones get the job for constructing the course according to Maxwell’s plans.

Mr. Todd explored several possible candidates. In response to an inquiry from Mr. Todd to the Merion Cricket Club, Mr. Philip Staples, chairman of the Greens Committee, replied on May 17, 1934 as to the qualifications of Toomey & Flynn. Mr. Staples indicated that the firm,

“…is very well and favorably known in this section. It has done very effective work at Merion and is, I think it fair to say, progressive in its methods and moderate in its charges.†Mr. Staples went on to say that “Those previous chairmen had, I know, much to say about the general outline of the courses when they were constructed, and it may be debatable as to whether they or Toomey & Flynn had the principal say in the determination of such design.†However, Toomey & Flynn have been consulted at all stages, have had in charge the construction work proper, and are in my opinion, entirely capable of taking on major projects.â€

On May 18, 1934 Mr. Jay Downer, chief engineer of the Westchester County Park Commission wrote to Mr. John D. Rockefeller, 3rd that golf architect, Tom Winton, was available for the project. As a follow up to an inquiry into Mr. Winton, Mr. Todd contacted the head professional of the National Golf Links of America, Mr. Alick Gerard, who stated that he never heard of Mr. Winton or his work. Mr. Gerard said that in his opinion the best golf course architect in America was Donald Ross.

Clarence Geist, developer of the Seaview Resort in NJ and the Boca Raton resort in FL wrote to Mr. Todd on May 21, 1934 on behalf of Toomey & Flynn. Mr. Geist wrote,

“In regard to Toomey and Flynn as Golf Architects, I wish to say that I have had them build three golf courses for me. Mr. Toomey died last fall and Mr. Flynn is carrying on the business. Mr. Flynn has always been the Golf Architect for the firm. He is a splendid Architect and a very nice man to work with. I will add that if I were to build another golf course William Flynn would be the only Architect I would consider.”

On May 24, 1934 Mr. Todd wrote to John D. Rockefeller, III about the layout of the golf course.

“My recommendation would be that when you are ready to go ahead, you get either William Flynn of Toomey & Flynn, Philadelphia; or Donald Ross of Pinehurst, North Carolina, to make the preliminary layout.

Neither one is awfully good; because from my experience and inquiries to date, I don’t believe there is a competent golf architect in either the United States or England. You will have to work with the best available, and it is my opinion that Messrs. Flynn and Ross come nearest your requirements.â€

Mr. Todd researched and considered Flynn’s work at Pine Valley Golf Club and Shinnecock Hills Golf Club and found both to be very much liked by the members with whom he communicated. Despite Todd’s opinion of American and British golf architects, the family went ahead and hired William Flynn to plan and build the golf course. Advantages which surely appealed to the Rockefeller family and their penchant for value and hard work, was the fact that Flynn and Toomey and Flynn could provide design, construction, agronomy and maintenance expertise all in one.

John D. Rockefeller, III and Nelson Rockefeller investigated the annual expenses for maintenance budgets at various golf clubs to determine the long-term costs of maintaining a golf course at the estate. If the maintenance costs were deemed high, they would not have approved going ahead with construction of the new course.

They certainly made this point clear to William Flynn. However, Flynn felt compelled to discuss his methods of construction and how they differed from usual practices,

“…our method of building Golf Courses varies somewhat from the general practice in that we use considerably greater quantities of material in developing construction. This is brought about by blending slopes naturally into surrounding surfaces, so as to present a pleasing effect to the eye, and not marring the landscape. Naturally this sort of construction is more expensive than that obtained from stereotype ideas, but in the long run great savings may be effected in the maintenance expense by the elimination of costly hand work.â€

Mr. Todd inquired as to the means of determining an intelligent estimate of the cost for building greens. Flynn replied,

“The answer is, that we, like Insurance Companies, for example deal in averages. The average cost of a green at Pocantico Hills will be the same as the average green on any similar topography, and we have built hundreds of greens on such ground, keeping accurate costs of the work.â€

The scientific approach to golf course design and construction by William Flynn would have appealed to John D. Rockefeller, Jr. who as a child kept careful record books of his income and expenses as his father did before him and his children did after him. The family grasped scientific methods and new ideas in business and appreciated careful and comprehensive record keeping. Flynn’s company with the legacy of Howard Toomey’s careful record keeping and the scientific approach of an engineer was perfectly suited to work with a family who knew exactly what they wanted after careful study and demanded excellence in all who worked for them to achieve their goals.

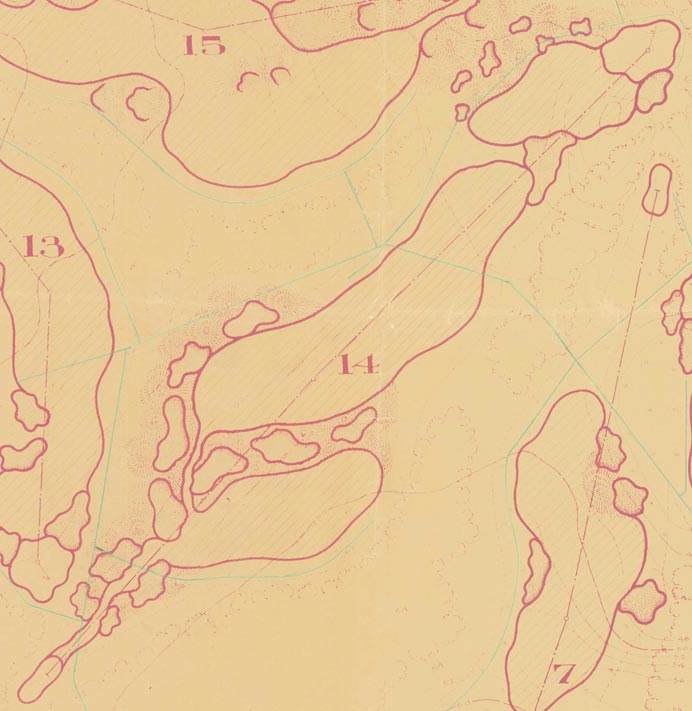

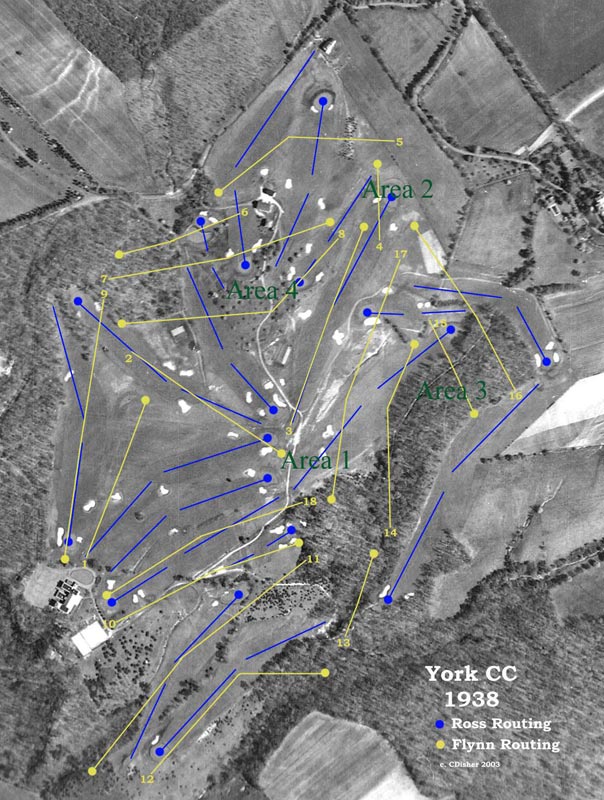

(18) Donald Ross and Flynn submitted plans for the same piece of property at Country Club of York. The clubhouse location was pre-determined. How did the two plans differ?

It is relatively rare that two architects were asked to prepare routings for the same property at the same time. It is even more rare when those two architects are giants of the Golden Age. In late 1925 William Flynn and Donald Ross were asked to submit routings to the Country Club of York for the club’s new golf course to be built in York, Pennsylvania. Each visited the property and each completed his proposed routings at approximately the same time. Whether or not they knew it at the time of planning, they were participating in a design competition for the County Club of York job.

The new course for the Country Club of York was constructed in 1926 based upon the plans submitted by Donald Ross. Now, some eighty years later, that competition provides a unique opportunity to compare aspects of the Flynn and Ross design philosophies. At York it is possible to hold constant the things that typically make comparisons of architectural styles so elusive. The location of the clubhouse, maintenance buildings, parking lots and access roads were all set at the time the two designers submitted their work. The differences in their routings are solely the result of different design preferences and philosophies.

The respective routings highlight two very different architectural approaches to the County Club of York property specifically and to golf course design generally. Contrary to the old axiom, the competing Flynn and Ross routings for the County Club of York property prove that topography is not destiny. Flynn and Ross routed and designed radically different golf courses. Areas on which Flynn located numerous greens and tees were areas that Ross skirted. Similarly, areas around which Ross centered his routing were areas that Flynn barely used.

Flynn had far fewer parallel holes than Ross. Crossing contour lines much more so than Ross would have made the Flynn routing a more difficult walk. How differently would these two courses play? Flynn’s routing is clearly the bolder of the two. The most difficult terrain on the County Club of York property was at the heart of Flynn’s routing, and the resulting holes would have been challenging even for the scratch golfer. His proposed that the fifth, sixth, seventh, thirteenth, fourteenth, fifteenth, sixteenth and seventeenth holes all either traversed creeks or had green sites perched next to steeply sloping creek beds. These holes would have involved testing carries or features at the green that would have severely penalized mishits. These holes would have been difficult for the weaker player, they also would have formed the heart of a thrilling, championship test for the strong player.

Ross’s routing reflects a very different architectural perspective. If Flynn routed eight holes across or near creek beds on the County Club of York property, Ross largely avoided those areas. On the routing comparison aerial, note the wide gap in the Ross routing between the line formed by his fourteenth and fifteenth holes and the line formed by his eleventh and sixteenth holes. That large area completely unused by Ross, is the creek bed that Flynn makes the centerpiece of his design.

At the County Club of York Ross sought to route holes along contour lines while Flynn selected opportunities to route against or perpendicular to contour lines. Certainly their disparate treatment of the creeks and their steep surrounds bears that out. But it can also be seen on the holes Ross routed at the edges of the property. His fifth, thirteenth and fifteenth holes lie well outside the perimeter of Flynn’s routing, all running along the property’s boundary lines where contours are more gentle. Again, Ross elected to use the flatter terrain for the mid-bodies of his holes. In contrast, Flynn’s routing sought to incorporate some of the severest terrain on the property for his mid-bodies. As a consequence, the Ross routing was probably both more forgiving for the weaker player and easier to walk, considerations that clubs like the County Club of York might have given great weight.

The extraordinary boldness of Flynn’s proposed twelfth through seventeenth is remarkable. His twelfth fairway would have dropped to a green diagonally fronted by a creek. The thirteenth, a par three, would have climbed out of the creek bed to a green perched into a slope, its right side guarded by a steep fall-off with the creek at the bottom. The fourteenth would have been a long, steep uphill par four routed through a heavily wooded gorge. The fifteenth, a par three, was uphill again to an offset green. The sixteenth would have started with an elevated tee, dipping into a small depression mid-hole, and back uphill to a well-bunkered green. The seventeenth would have tracked back along the western edge of the creek, the fairway sloping hard from right to left, culminating at a green dangled at the edge of severe left-side fall-off. These would have been tough, exciting and beautiful finishing holes. Disaster would have stalked every shot.

Ross’s reluctance to engage such hazards so directly in his designs is consistent with his view that greenside water and other greenside hazards should be used sparingly. He also eschewed forced carries and tried to avoid them if possible or minimize them when the land gave him no choice. It seems fair to say that Ross’s courses tend to be more forgiving from tee to green. He preferred to concentrate his hardest challenges at the green. Consistent with those views, the Ross routing for the County Club of York property minimized the use of the property’s most severe natural hazards, but his greens at the County Club of York are enormously challenging.

(19) I grew up playing the James River course at the Country Club of Virginia. A fine course, still it is underwhelming relative to Flynn’s other work. Why is that?

For the simple reason that Flynn did NOT design the James River Course for the Country Club of Virginia. The Flynn collection of drawings contained designs for two courses for the CC of Virginia, the Hill Course and the Valley Course. Only one course was eventually built and neither of the two Flynn plans corresponds to the James River Course. There were some similarities between individual hole plans and the course as built, yet no routing progression could account for the similar holes. We were left to conclude at the very least, Flynn did not design the course according to the two sets of plans we had and that any similarity was coincidental.

Craig Disher found a July 19, 1934 Washington Post article which indicates it may not have been a question of having a incorrect set of plans, but that Flynn likely did not design the golf course at all, but instead Fred Findlay.

(20) Okay, okay. We get the point that Flynn was a master! What weaknesses do you see?

In fact, very few. In studying his weaknesses, his strengths become even more apparent. Certainly the revisions to the 2nd and 16th holes at Lancaster Country Club years after Flynn’s death were vast improvements over Flynn’s designs. The eighth and ninth holes at Philadelphia Country Club, while solid holes, are not up to the same level of brilliance found on the other sixteen original holes. Well today it is fifteen, as the revised 18th (William and David Gordon) was significantly compromised with the clubhouse being moved in the original hole corridor. At Rolling Green Golf Club, all the par three holes have a single bunker at green level on one side and multiple bunkers below green level on the other. They are all outstanding holes, but that is a bit repetitious. Overall, I think there wasn’t another classic era architect with such a strong batting average of course designs. While Shinnecock Hills is his most illustrious original design, he was consistently strong in his overall portfolio. If you think about the number of major championships (especially in recent times) on the fifty or so courses which Flynn designed were built compared to other architect’s much larger portfolios, I think one can get a sense of how well Flynn did. Also, a lot less redesign work was done on Flynn’s courses as they have stood the test of time better than most. Design elasticity is one factor. But keep in mind, Merion’s bunkers haven’t been changed (other than depth in some cases) in 76 years. Even with the modern game, the bunkering is not obsolete for all classes of players. Can you say that about Macdonald, Raynor and Banks? There are only a handful of American architects that seemed to prepare their courses for the evolution of golfers and their equipment. It is interesting to speculate what Flynn’s ultimate legacy would have been like had he lived another twenty years or so into the middle 1960’s.

Flynn’s designs such as Merion, Lancaster, The Country Clubs at Brookline and Pepper Pike, Rolling Green, etc. have stood the time very well. While he had few weaknesses, the fact that so many of his courses have passed the test of time is a tribute to his greatest strengths, outstanding routings with hole design and construction guided by sustainability principles enabling his courses to be maintained for reasonable cost over the long term. There are rarely any level lies on Flynn’s fairways. The ball striking requirements are very high and golfers simply must learn how to control the shot shape and trajectory to perform at a high class of play. The offset angles of fairways and greens as opposed to straightaway holes helps to stave off the effects of modern technology and stronger players. The mental test in combination with the physical execution demands identifies the complete golfer. The subtle interplays of slope on the greens require a deft ability to read greens and execute the proper line and speed.

(21) Where do you stand with your cornerstone book on Flynn’s work?

I guess this was an inevitable question. The book is essentially finished. Steve Rockefeller, Jr. is completing some personal remembrances about the Flynn course on their family estate in Tarrytown, NY. He has completed the majority of his contributions to that chapter. Otherwise, the book is complete. At present it is a weighty 2047 pages. I am working with someone to publish it on DVD in a format that cannot be copied and protect the images with watermarks should someone try to download the images. If anyone in GCA.com land can help in that regard, I would greatly appreciate it. We also believe we will print 100 5-volume sets in the not-too-distant future.

(22) What’s next on the horizon for you?

I enjoy researching and writing about golf architecture and during the writing of the Flynn book, Tom Paul and I have worked on a practical application of our studies by helping clubs with their architectural evolution reports and even go so far as preparing long range restoration and master plans for clubs such as Shinnecock Hills and Cascades. Given that Flynn accurately drew his plans and the courses were accurately built to those specifications it was simple to organize a presentation of what was planned, what was built and what now differs from those plans. For clubs that wanted to go back to the original design intent, along with Craig Disher and others, we were able to provide the means to know what was, what is and what can be once again.

Jeff Silverman and I recently formed a partnership, The Golf Historians, to provide three services to clubs:

1. Advise on how best to assemble, structure, catalogue and maintain a viable archive

We’ll help you identify what you have, what you need, and where to go to find what you’re missing. We’ll also show you how to get the membership involved in the process, how best to display photographs and other memorabilia, how to manage and preserve the collection, and how to create a searchable database of the archive holdings.

2. Create golf course evolution reports

The heart and soul of the club, the course itself is a living organism, subject to time and tampering, the pounding of nature and the whims of green committees. Using whatever tools are available – aerial and other photographs, architectural drawings, and anecdotal recollection – we will prepare a report that carefully examines how the course has changed over time, who made those changes, and why the changes were made. Such a report is a necessary tool to help committees and memberships make the important decisions they need to — about maintenance, restoration, renovation, and conditioning – that impact the golf course both now and in the future.

3. Prepare club history books

When professionally done, a well-researched, well-written, and well-designed club history gleans from the above to accurately and entertainingly twine together five essential strands that we maintain will do much to identify and reinforce the essence of your club, whether you’ve hosted U.S. Opens or just your own member-guests.

First, every club has its own unique story to tell, and a history can give it form in a way that members and guests can actually hold in their hands.

Second, a club history is an easily consultable repository of the club’s memories and its records.

Third, the history helps capture and define the architectural heritage and development of the golf course, and the legacy of the designer.

Fourth, it helps promote the cachet of the club in an elegant, sophisticated and classically understated way to current and prospective members alike, making it as much a marketing tool for the club as a keepsake for members and guests.

Finally, by introducing new and prospective members into the club’s ethos and reminding the veterans of what they have, the kind of polished and professional club history that we offer fosters club camaraderie by serving as a generational link that further connects and unites an already proud membership.

CONTACT INFORMATION

Wayne S. Morrison Jeff Silverman

wsmorrison@thegolfhistorians.com jsilverman@thegolfhistorians.com

610.955.5686 cell 610.247.8734 cell