Feature Interview with Owen Larkin

July 2012

The Vineyard Golf Club on Martha’s Vineyard opened in 2002. As managing partner and founding president, you were ultimately responsible for every aspect from permitting through construction. Given the tight environmental restrictions for which Martha’s Vineyard is famous, permitting must have been some process. What were the keys that allowed you to press ahead with the project?

To say that permitting was arduous would be an understatement. At that time there were three groups trying to be approved to build private courses on the Vineyard simultaneously, so the island was feeling besieged. We knew only one course- if that- would be approved. There was a great deal of mistrust and a feeling that golf would do nothing but degrade the environment.

Others had better political connections, but I believed going in that if we stressed doing right by the environment our project would prevail. As far as I was concerned, the key to making it work, was trusting the integrity of the local Boards that uphold and protect the environmental rules & regulations on the Vineyard. Our main competitor needed relief from the Conservation Commission to obtain a waiver in an effort to site their golf course closer to one of the Great Ponds. If they had received it, their project would have prevailed over mine. We spent well over a year stressing our model of environmental stewardship as opposed to a model that required the lifting of environmental protections. At the end of two years of rigorous community vetting and struggle our project was deemed by the local and state regulators to be the most environmentally benign, and therefore we were the only project approved.

During the permitting process we offered to make our golf course the most environmentally sensitive in the country. The Martha’s Vineyard Commission then upped the ante, by requiring that the course be organic. At that time no golf course was being maintained using that restrictive a protocol, especially a high end, 18-hole course like we were proposing. Although it was a greater challenge than we were anticipating, we agreed to take it on. For the first few years of our project there was intense scrutiny because no developer in the country had achieved what we claimed we could do organically, then there was scrutiny because folks couldn’t believe their own eyes. They couldn’t get over how good the course looked, and played, without the use of herbicides and fungicides.

The most important factor for success is our ongoing environmental management plan. We share this through quarterly review committee meetings with community representatives. Over the last half dozen or so years the Review Committee has evolved into one of our valued resources. Because of their level of cooperation and involvement we are able to test products and practices from academia and industry. Hopefully Martha’s Vineyard will also become famous for its community participation model that has enabled the Vineyard Golf course to become the model of sustainability that it is.

The natural vegetation lends a rich texture to The Vineyard Golf Club on Martha’s Vineyard.

Was it trail and error in determining which bio-stimulants and composted fertilizers to use in place of conventional pesticides?

It was one thing to successfully permit and build the course; the harder task was making sure that that our sustainable protocols worked. As with any new management protocol there is a certain amount of trial and error. There are numerous and varied products and modalities that we’ve tried through the years. I would say it has been more a case of adjusting each experiment based on the on-the-ground feedback.

Luckily, because we have been the leaders in this nascent movement we get the opportunity to work with academia, industry and some really smart, well-intentioned people. Quite importantly, we have worked in collaboration with the Environmental Institute for Golf, the USGA Green Section, selected university professors, fellow superintendents and some local Island gardeners to determine the best products. As we learn more and more, we get better and better, not only in our day-to-day management practices, but also in our ability to react to new adverse conditions that may appear on our golf course.

Was your involvement with The Vineyard Golf Club the genesis for the Larkin Group?

Absolutely! My goal in 1997 was to build the most environmentally sensitive golf course in the United States. For the last decade our superintendent Jeff Carlson and I have overseen the management of the Vineyard Golf Club. When we started this back then we were real outliers. Now I feel we’re in the right place at the right time- ready for the market with experience and unique know-how when the market is finally ready for us. Not only has “sustainability” gained wider acceptance and visibility in the marketplace in general, it is becoming more of a necessity and a desire in the world of golf.

I had been working on bringing our superintendent, Jeff Carlson, and some other key players together to build a sustainable golf company, but when the International Olympic Committee voted to have golf return to the Olympics – and then when we heard they wanted the course to be sustainable – I knew the time was right. I decided to gather some of the top people we’ve worked with over the years into a collaboration called the Larkin Group.

The better the environment, the more enjoyable the golf.

In one paragraph, what is the business mission of the Larkin Group?

Our business mission is to help lead the golf industry in sustainable practices to build new courses, renovate existing ones and guide courses in using more environmentally benign systems that protect the land and those who spend time on a course or live adjacent to it. We will help our clients address the increasingly strict regulations on water and product use, and institute sustainable management practices that will allow those clients to stay in business as responsible neighbors.

Who are the key people involved?

The key members of the Larkin Group Team are Gil Hanse- our principal golf course architect, Amy Alcott- a golfing legend and course designer, Jeff Carlson- the certified superintendent of the Vineyard Golf Club, Dr Frank Rossi- a turfgrass science specialist at Cornell University and Bob Ford- head of golf operations.

The Larkin Group acts as an umbrella organization to bring these amazing professionals together on a project basis. This gives our clients the opportunity to work with a group of industry leaders, from different disciplines, who don’t typically work as a group. All of our chief team members will maintain their current businesses and positions. Those continued associations benefit the Larkin Group tremendously because of the ongoing research and communications our key people will have within their specific fields.

We also have a teaming agreement with AECOM, a Fortune 500 Engineering, Environmental and Design firm. AECOM has about 45,000 employees in cities all over the world so they’re huge and can handle any size project. Engineering News has ranked them the number one Environmental Engineering firm in the world.

The in-house administrative staff also includes John Gunderson our environmental attorney, Scott Westfall- Senior Project Manager and Marjorie Reedy Larkin who handles Communications and Strategic Marketing.

You consider yourself a ‘pragmatic environmentalist.’ From a business point of view, what are the benefits?

In a word: “flexibility”. I think people are sometimes afraid “environmentalists” will have a singular focus. I have one foot in the golf world and the other in the environmental world, and have hard-earned credibility in both. So, particularly in difficult situations, we can present to both sides the most real-world solutions, defining what will and what won’t work. The bottom line is that we have the portfolio and credibility to “walk the walk” of both camps, and that is a huge asset to our clients. Our team has the experience and resources to present to a client the best plan for a particular piece of dirt in a particular microclimate. We do not adhere to a boilerplate plan that is site modified, instead we tailor-make a program that best adapts to the specific situation at hand. We protect the natural resources without compromising the playability and beauty of the course.

We look at what we do as trying to balance the needs of all concerns. As far as the Larkin Group is concerned, “sustainability” boils down to three things: the quality of the golf course, the economics of the business and the soundness of the management practices. You must pay attention to all of these to have a successful project.

In this time of economic struggle so many golf courses have gone out of business or are trying to reposition themselves so they don’t go out of business. Add to that the difficulty of dealing with the rising cost of water in some parts of the country and the growing restrictions on water in others. Some people will adopt what we do because they feel they’re doing the right thing. Others will be forced to make changes and we can help ease that process.

Though it seems like an eternity ago, the golf course development business was thriving in 2005 and Al Gore’s widely seen An Inconvenient Truth had yet to come out. Now, golf course development in North America is moribund and the concept of ‘green’ is everywhere. Are you startled by how quickly this came to pass?

Yes I am. I believed that the ” green ” movement was inevitably going to grow; yet I was not as optimistic on the time frame as some others. In tough times any business must get more efficient in its utilization of resources. Golf got a double whammy with less player participation and more costly regulations. So to me, managing a golf property in a “green” or sustainable manner is a competitive advantage, and that will probably be the largest accelerator of this movement.

About a year after, An Inconvenient Truth, came out Trent Bouts wrote an article entitled “A Convenient Truth” in which he interviewed about a half dozen people in the golf business regarding golf and the environment. In my mind the minimalist movement led by Bill Coore & Ben Crenshaw, Tom Doak and Gil Hanse has morphed into golf’s “green” movement. In that article Tom Doak so accurately talked about golf courses needing to become communicating neighbors. As an industry we are getting much better at that.

The fact that the Brazilian Olympic Committee stressed sustainability for the Olympic Course should make environmental sustainability even more prominent on the world stage. The president of the Rio Olympics said this course would be “a new beginning in the history of the sport.” In our presentation David Fay, the former executive director of the USGA, made a statement via videotape about the importance of sustainability in the future of the game of golf.

Tell us about the benefits of controlled burns.

Fire is a wonderful tool to control weeds and unwanted growth in out-of-play areas. The controlled burn eliminates the undesirable plants, allowing the native grasses to flourish. The residual ash provides a source of minerals for the soil. As the native grasses come to dominate the site they will naturally out-compete the invaders. The burn must be done at the right time though. In order to reduce weed infestation it is important to burn when weeds are actively producing seed head. Basically the burn eradicates existing weeds and its seeds, thus allowing other turf species to have a better chance to compete.

A controlled burn in progress.

Are lysimeters fundamental to each and every one of your projects?

In order to manage your golf course properly you must be able to measure if there is any product residue. In other words—“what are you putting back into the water table?” We have found that the lysimeters are quite good as early detection systems for product or nitrate residue. Lysimeters, or some type of tool that helps the superintendent know whether the turf is utilizing as close to 100% of product as possible, are fundamental.

Consulting with existing clubs is a big part of your offering, especially with new course construction in North America at post World War II lows. What are the most common areas where you see waste?

I’d say the number one common area of waste is using too much water. In reaction, some communities have taken away water rights from some golf course. What’s important to note is that restrictions are only going to get stricter as water becomes more and more precious. Unless we find better ways of utilizing lower quality waters, golf will be denied, or prices out of water.

Courses also use too much product such as fertilizers, insecticides, herbicides, and pesticides. These products may take care of the immediate problem, but can increase future insect and disease problems by killing beneficial soil organisms. Without those organisms, thatch doesn’t decompose, and the efficiency of any input is significantly reduced. So then you have to add more inputs to try and keep the system in balance. This chain of “product to combat the ill effects of previous product” becomes nearly inescapable.

Some other areas of golf club waste are the Food and Beverage packaging like coffee cups, on-course snacks, and water bottles. Water runoff on impervious parking lots and roofs is a waste. That water could be captured and harvested. And as for riding cart maintenance, why not use off-peak charging meters?

My point is that the first few items are the low hanging fruit. However there can be many more efficiencies – therefore savings – if the whole system of management is analyzed. I think there is a lot of passive waste, in that many courses are not as efficiently thought out and managed as they could be.

On another level, think of all the water, labor, energy and equipment depreciation, that a course could save if managed turf were reduced by 5-10 percent. In many instances these reclaimed out-of-play areas can be further used for water harvesting, which is another savings.

Turf selection is crucial for getting the right playing characteristics as well as setting the stage for less inputs like water and chemicals. What have been some of the most exciting developments in turf research in the past five years?

There has been continued development of bent grasses that use less water and have bred resistance to diseases in the Northeast, increased development of seashore paspalum and new varieties of dwarf Bermudas in the South and new zoysia grass cultivars in the transition Zone and in the South.

I’d also have to say one of the most exciting developments in turf research has taken place at the Vineyard Golf Club on Martha’s Vineyard. As an organic course we have never used synthetic fungicide on our grasses, which are a mixture of fescue and colonial bent grass on the fairways and creeping bent on the tees and greens. Over the ten years we’ve been in operation we’ve seen a change. The grass is better conditioned now than it was ten years ago. It’s becoming more resistant to disease; there are far fewer problems on the greens.

Our superintendent Jeff Carlson thinks this is a function of two things: first that a natural selection process is taking place, as is common in breeding, a survival of the fittest is going on as our grass is evolving. And secondly he believes that synthetic pesticides affect the microbiology of the soil. The more pesticide that’s used, the more the plant relies on that pesticide rather than its natural defenses, so more pesticide is needed to keep the plant healthy. It’s similar to the way antibiotics become less effective the more you take. We believe because our grass has never been exposed to synthetic pesticides it is more adept at fighting disease with its natural processes.

Chemical companies are moving in the right direction by developing more benign products to the environment. What are a couple of your favorite products that have recently come on the market?

We do not endorse specific products. But the industry as a whole has become very dynamic and responsive to environmental pressures. Amounts of active ingredients have been drastically reduced and synergistic relationships have been explored between small amounts of synthetic pesticides and low impact, non-synthetic products. Even major chemical distributors are developing growth stimulants and plant health enhancements these days. In the new product lines they are taking a holistic approach, focusing on overall plant health instead of targeting specific disease.

The Larkin Group was part of the Hanse Golf Design that presented to Rio 2016 Olympic Committee. Tell us how that went.

Clearly Gil Hanse is the predominant reason our team was selected. I think his beautiful minimalist design and his commitment to on-the-ground oversight was a huge advantage. But in addition to focusing on the design, Gil thought it important to address the sustainability requirements of Rio 2016 with the same degree of weight that they presented to us in the RFP and the workshops. Each team had 45 minutes to make its presentation to the jury. So every minute was precious!

I spent nearly a third of that time talking about sustainable practices. The greatest benefit for me personally was the validation of what we have been doing for the last dozen years. The fact that sustainability was a requirement and not an afterthought, and according to the president of the Brazilian Olympic Committee that they want “sustainability to be the Game’s legacy”, is to me a ground shaking change.

Also within our presentation, LPGA champion, Amy Alcott, gave her impression of the Olympic course and how it might play for female pros under tournament conditions. She also discussed the teaching academy that will be built to teach the next generation of Brazilian golfers. I felt at the time that what we said (particularly Gil’s statements) resonated with the 4-person jury.

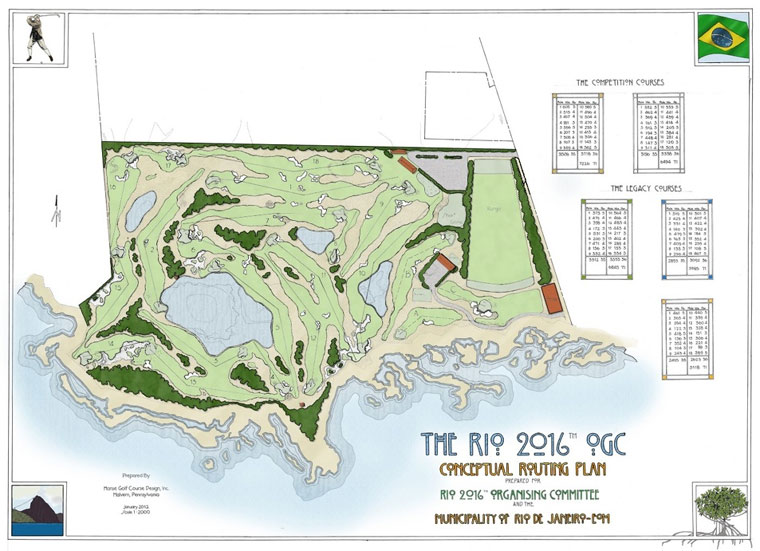

The winning routing.

At the end of the day Gil’s low key, yet compelling, description of how he views the golf course, the land, the role he and the Larkin Group will play and the integration within the landform and watershed, seemed to receive a positive reaction from the jury. I felt that way upon leaving the room back in January, and the verdict validated that feeling.

You are the Sustainability Managers for Hanse Golf Design for the Olympic course, which is to be built several miles south of Rio at the Reserva da Marapendi. Tell us about the opportunities and challenges there.

Other than its location this is not a remarkable site. Fortunately it is a very sandy site with a gentle decline across it. There are two large dunes that traverse the site, but other than that the interesting landmasses are primarily the result of some level of sand excavation. Gil has woven his routing through the terrain as he found it. He will take advantage of what is now haphazard mounding and water retention areas. We will then replant the out of play areas with native grasses and plants that will assist in water savings and harvesting.

The challenges primarily involve low water quality for irrigation and the fact that the land is a “reserve” or has conservation restrictions on it, and therefore our hands are tied regarding the amount of non-native turf that we may use. At this point we are evaluating how different turf will hold up under the cloudy conditions that predominate during Brazil’s winter (August) when the Olympics will be held.

As the Olympic course is located beside a lagoon, is this the ideal scenario for a reclaimed water system?

You would think so, but unfortunately no. In this case we will not be drawing water from the Lagoon and in fact its surface water contains many pollutants. I believe that anytime we can use already used water we should strive to do so. We will intercept storm water that comes from off site, harvest and store it, filtrate – or make it cleaner – and then use it to irrigate the golf course. This same water will go through another natural filtration as it works it’s way to the groundwater after irrigating the golf course. I include storm-water as reclaimed water because we will intercept, slow down, harvest and filtrate this water and thereby integrate the golf course into its micro watershed area.

The greater opportunity for reclaimed water will be the integration of the golf course with the high-rise condominiums that will be built, abutting the site and slightly above the golf course parcel in the watershed, after the Olympics. There are many opportunities to capture non-effluent grey waters from these residences. After capturing these waters they would go through the same processes as the captured storm water. This will allow the golf course to need less water from the aquifers and municipal water supplies. This will provide economic benefits in many cases as well as help show that the golf course is a responsible member of the community.

Above is a rendering of the Rio Course for the 2016 Olympics.

What is the microclimate like? Can grasses be used that are conducive to the ground game?

Rio de Janeiro has a tropical savannah climate characterized by a distinct wet period from December to March and a relatively dry period from May to October. We are currently analyzing water quality, daily sunlight during Rio’s winter season (during which the Olympics will be held) and turf acclamation during this predominantly cloudy season.

As of today we have not yet concluded which turf will best satisfy those elements and provide the best playing characteristics for both the Olympics and the public venue post Olympics. We will absolutely utilize turf and recommend management protocols that will allow a bump & run style on our well draining site. This of course is driven by Gil’s design and the elements he wants utilized.

Does any one country employ maintenance practices that are noticeably friendlier to the environment?

In general, Canada and the European Union have more environmental awareness than most parts of the golfing world. Specifically the links courses of England, Ireland and Scotland employ sustainable practices. To be fair, it is easier to implement and practice sustainable modalities in these microclimates, because of cooler temperatures and annual rainfall which allow for less human intervention. Sustainable management can be implemented anywhere, however more care and analysis will be required in particular regions.

Does any club in particular stand out for egregious maintenance practices that harm its surrounds? Are you familiar enough with Augusta National to comment on its practices vis-a-vis the environment?

We make it our business not to criticize any club’s practices. I have no first hand knowledge of any policies of Augusta National therefore my comments are based on anecdotal information.

Golf courses that endure any of the microclimate, and in particular the moisture problems that Augusta National has benefit from the technologies and management practices developed there. A lot of courses cannot afford those initial technologies, but most benefit from the sharing of information from the beta site that Augusta National has de facto become. Some information is passed on through superintendents, and new, less expensive technology is made available to the industry as a whole.

For me that huge benefit to golf far surpasses any cost of putting “ice cubes on the azaleas”. I use that metaphorically because I think that the comparison of Augusta National to most any other typical golf course is fundamentally flawed. I think it should be viewed through the prism of being the host of a huge reoccurring, international, entertainment event and judged on its environmental and sustainable practices for that event. Most clubs in the world can’t be compared to Augusta National since it is a seasonal course, closed for many months each year, which, uniquely, is not dependent on member revenues to underwrite operations.

Man is increasingly disconnected from nature as he surrounds himself in a concrete jungle full of plastic devices that he uses on a daily basis. Golf in theory should be viewed as a nature and wildlife haven yet in many cases it is not. Where did its message/appeal get derailed?

I have a different perspective in that I don’t think the message has been derailed, in fact I believe there’s been a concerted drive by golf’s support agencies like the USGA, the Environmental Institute for Golf and GEO (Golf and the Environment), to emphasize the open space attributes of golf courses. Golf courses by their nature provide habitat for a variety of songbirds and predatory birds. At the Vineyard Golf Club, management practices have successfully attracted many other species also, at times our golf course seems like an aviary.

What will it take for the benefits of having a neighborhood golf course to be viewed in a better light?

It is the neighbors who will be viewing or judging the golf course in their community. They will ultimately be the ones to decide the allocation of resources and approval of products that can be used on a course. So it’s best to make peace with the decision-makers.

You have to take the subjectively and the prejudices of golfers out of the equation. Let’s say so that there will be no bias amongst the “judges”, remove all golfers from the judging panel. Now we have a pool of folks that are only looking at the benefits and detriments of a parcel of land and the way it is used for their community benefit. At the end of this analysis the golfers at any individual course now understand what the “non-golfing judges” value. This should be the foundation for devising plans for how the course can contribute to the neighborhood in ways that the neighborhood desires. It could be something like rebuilding a stream bank so as to mitigate flooding. It doesn’t hurt the golf course and may in fact help it.

Every season brings new environmental situations to a course as well as the community. Both will benefit by working together for the benefit of each other. At the end of the day, golf course operators need to understand what motivates the people who live near and around the course so that the golf course can be viewed as part of the solution. If we get to that point, we will be viewed in a better light.

THE END