Ralph Plummer, Golf Course Architect

by Lou Duran &Jeff Brauer

August, 2006

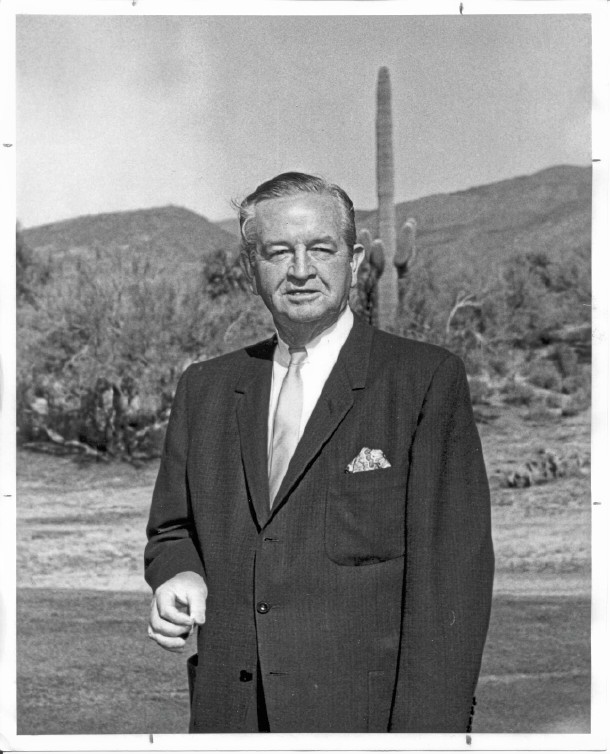

Ralph Plummer ASGCA

Part Iby Lou Duran

Historically, golf course designers or architects have come to the profession from many different backgrounds. Their personalities, demeanors, training, and approach to their craft have varied considerably. Some practiced obscurely in limited regional areas with little promotion or fanfare. Others were master marketers with an eye for a headline and wide acclaim.

Without question, Ralph Plummer belonged in the first group. Though he designed, built, or remodeled some 100 courses including three that hosted the U.S. Open, his name is hardly recognizable outside of Texas. And despite a very productive, 40 yearlong career, Plummer’s hometown newspaper, the “Forth Worth Star Telegram”, could only locate five articles devoted to him in its archives.

Born Olaf Joseph Plummer in 1900 near Fort Worth, he did most of his work in his home state and died within miles of his birthplace in1982. Disliking his given name, he changed it to Ralph, though he came to be known as “Rabbit” or “Rab” by his friends and colleagues.

As a 12 year-old, Plummer was introduced to golf in the caddy yard of Glen Garden Country Club (preceding Ben Hogan and Byron Nelson there by more than a decade). He learned to play the game the old-fashioned way: through observation and trial and error, and became an accomplished local amateur, winning numerous matches and tournaments.

While Plummer attended Texas A & M briefly, no information was found that he had much formal education beyond high school. His ties to this land grant university, well known for its turf and agronomy programs, were re-established with his 1950 design of a student golf course on its campus, and much later as a visiting instructor of agronomy.

Though Plummer played some golf professionally, making a living on tour during slow economic times and miniscule purses was not in his future. That he could play the game at a high level is supported by a newspaper account of his win at the 1930 “Fort Worth-Dallas Pro Golfers’ Sweepstakes”, besting future two-time U.S. Open and Masters winner Ralph Guldahl by three strokes. Masters and PGA winner Jackie Burke, Jr. remembers Plummer as a very good player who could shoot 75 or better while playing little golf due to his hectic work schedule.

Plummer did not come from money, nor does it appear that he was able to amass a consequential fortune in his long construction and design careers. His first job as a professional was at a 9-hole course in south Texas where he was hired to assist noted golf course architect John Bredemus with its construction in 1927. He stayed on after its completion and eventually became the head professional.

As in many parts of the country, the Depression hit the Texas golf business very hard. Plummer persevered the best he could, sometimes working with Bredemus on whatever golf jobs they found; other times by taking on odd jobs including one as a clerk in a shirt store and another at a downtown Fort Worth betting parlor. Later, during WWII, Plummer reportedly built asphalt runways for the U.S. government.

In 1935, Fort Worth business leader Marvin Leonard hired Bredemus to design and build what came to be known as that architect’s seminal work. Colonial Country Club was conceptualized to be unlike anything else in this part of the country, with all the modern amenities and cool weather bent grass greens.

Bredemus in turn hired Plummer as his construction foreman. To this day, there is disagreement regarding the relative contributions to what has become Texas’ most famous course, and, inarguably, still one of its finest. While it is accepted that Bredemus was principally responsible for the routing, Perry Maxwell is often associated with the greens and the changes to three holes prior to Colonial hosting the1949 U.S. Open.

However, two of Plummer’s contemporaries with impeccable credentials, Byron Nelson and Jackie Burke, Jr., independently stated that Plummer had a very large role not only in building Colonial, but also in the course’s design and later improvements. Off the record, a source closely associated with Colonial remarked that he believes Plummer’s design contribution was significant, though there is little in the club’s history to verify it.

During this period, Plummer also built Houston’s fine municipal course, Memorial Park, for Bredemus. No doubt taking cue from his mentor and employer of nearly 20 years (who also designed and worked extensively on the site), Plummer had considerable license in what was constructed on the ground.

Plummer’s design philosophy was probably borne out of necessity as much as anything else. One employer noted that the architect willingly worked for “next to nothing” on very austere budgets. Likely owing to financial need, and perhaps resulting in his nickname, Plummer was known never to sit idle, scurrying to his next tournament, design, or construction job like a “scalded rabbit” immediately upon completing an assignment.

To clients and co-workers, Plummer was known as an honest, no-nonsense, task-oriented individual. A former laborer on a project recalls Plummer as being strict and intolerant of horseplay and indolence. Clearly, he was a serious man who didn’t suffer fools gladly.

Like his mentor, Plummer lived much of his life as an itinerant, going wherever the work took him. He appears to have been a bit withdrawn, perhaps shy, which may help to explain the difficulty in finding much personal information about him.

It was said that though he was quiet and followed his own counsel, he could talk endlessly about anything to do with golf. Plummer had a reputation for being very respectful and receptive to ideas from his clients. Though their personalities couldn’t have been further apart, Plummer and the colorful Jimmy Demaret (three-time Masters champion and co-founder with Jackie Burke of Champions Golf Club) reportedly had a warm relationship marked of mutual respect.

More than a couple sources mentioned that Plummer enjoyed his scotch in generous quantities. However, nothing derogatory surfaced about him while researching this piece.

Cornish and Whitten mention in their book “Architects of Golf” that Plummer was known for his ability to accurately calculate cuts and fill in his head, while building attractive golf courses. Others have noted the subtlety of his work. In actuality, Plummer was truly an “on-site” designer who loved to plan, strategize, visualize, and design his work with his clients and associates.

According to his daughter, Peggy Gunter (deceased), Plummer absolutely hated drawing plans and put them off as long as he could get away with it. Fortunately for the procrastinating architect, Peggy worked for a leading engineering firm in Fort Worth and she enjoyed and was skilled in precisely those aspects of golf architecture that her father disliked so much, drafting and drawing. This made for an association enduring many years.

By today’s standards, Plummer’s courses come across as rather plain, perhaps even unsophisticated. Yet, one can’t help but to note from even the first playing how well they flow with the land and that they possess considerably more substance than readily meets the eye.

Typically working with strict budgets, Plummer had to make the most from the sites he was hired to transform. Unfortunately, many of these included considerable flood prone acreage and did not possess an abundance of natural features with which to work. Though he often had to build up greens and tees, he did so in a softer scale, and his style had much in common with today’s Minimalist camp.

It is a great understatement when it is said that Plummer worked closely with the land. His career spanned a time frame when mule-drawn carts and scoops to bulldozers, backhoes, and scrapers were used to transform the land. He typically toiled right along with his small group of laborers, designing, cutting, filling, creating tees, greens, bunkers, hazards and other features with his hands and machines. The less he had to disturb the site, the more he was able to put into the features which made his courses memorable and challenging.

Though a very good player in his own right as previously noted, Plummer at times incorporated input from golf professionals in his designs. Both Messrs. Nelson and Burke remember that Plummer was very receptive to their ideas, but reported that their input was limited to specific playability and shot value issues. Plummer may have been somewhat autocratic in taking the plans he envisioned, incorporating the valid suggestions from his collaborators, and putting them on the ground.

Plummer did not bunker his courses extensively, probably because of their higher cost and the disproportionate impact of sand on the average player (relative to the expert). Instead, he employed whatever natural features and elements were present on the site- e.g. small elevation changes, hollows, mounds, streams, trees, occasional rock formations, and prevailing winds- to provide a stern test for tournament play, and an interesting, challenging, yet playable course from the forward tees for regular customers.

Typically, Plummer provided conservative routes for the less accomplished players, and kept forced carries to a minimum. His greens are generally open in the front, conducive for the run-up shot whenever soil and turf conditions allow for it.

In a candid 1965 interview published in the “Fort Worth Star Telegram”, Plummer allowed a glimpse of his design philosophies as well as a perspective of the game and the challenges it faced at that time. Amazingly, those same issues are valid today. Plummer was concerned with the effects of how far the ball was going as a result of improved technology, better swing technique, and higher competitive opportunities from high school through college to the pro tour.

He discussed how Augusta had to constantly change to keep up with the game, and was prescient in opining that narrowing the fairways and letting the rough grow would lead to the higher scores tournament officials were seeking. In what would surely apply to Tiger and Mickelson in 2006, Plummer noted (tongue-in-cheek) that Nicklaus was hitting the ball so well (and far), tournament officials “might have given him a saliva test”!

Plummer believed that there were several significant considerations in designing a successful course. Surprisingly, the site or its selection is not among them: “I’ve built them in mesquite thickets in West Texas, rice fields in Louisiana, and swamps in Jamaica” said Plummer. Instead, most likely reflecting the locales where he worked and tight construction and operating budgets, the availability of water for irrigation was paramount.

Consistent with where he learned and practiced his craft, the prevailing winds was his next consideration. He believed that a course should be laid out with cross winds so golfers would be encouraged to control the ball as opposed to only fighting the wind.

Taking into account the special allure of power in the game, he wanted his courses to stretch out to at least 7,000 yards (in 1965!), but still be challenging and playable for the average golfer from the shorter tees at around 6,300 yards.

Believing that the wind is the biggest obstacle for the expert player, he opined that heavy rough is often the only controllable option that kept a course from being irrelevant to the professionals. From a practical standpoint, it should be noted that managing the rough is probably the least costly and management intensive practice for a course which hopes to meet the objectives of its regular clientele and yet hold occasional high-level tournaments.

Plummer also believed in the symmetry of design, declaring that “each green should be sized to the approach shot needed, the longer the iron shot, the larger the green”. He also had no qualms about helping the player gauge distances, advocating the framing or use of trees and shrubs as backdrops.

Though possibly too formulaic for some and not easy to follow, Plummer tried to incorporate a few basic routing principles into his courses. He liked to run consecutive holes in different directions for variation of wind and other factors. Plummer routed fairways to minimize the effect of the rising and setting sun, and believed the first few holes should be par 4s or 5s to improve the flow of play. He also liked to mix the par 3s and 5s throughout the par 4s for variety.

Plummer’s opinion that trees and shrubbery are superior to sand bunkers by adding beauty and saving expense is reflected in many of his courses. He utilized native specimen trees to turn holes wonderfully and to provide preferred angles for approach shots. When budgets allowed, he planted ornamental trees and shrubs (Crepe Myrtle, Yaupon, and Magnolia in Texas) on the periphery for framing and aesthetics.

The pragmatic, practical side of Mr. Plummer was readily revealed when he cautioned that building the course is not the only thing that is important, but that it must be done in a way that it can be operated at a profit. “A good architect provides surrounding land areas suitable for home sites or some other practical purpose.”

To be an effective golf course designer and builder, Plummer thought you had to be a jack of all trades, as well as a master of most. “You have to know the game inside and out to build a course, and know soils, grasses, heavy equipment, hydraulics (for sprinkling systems) insecticides, fungicides, fertilizers, and other things.” He did not underestimate the advantage of being a good player in allowing the architect to design a course that is challenging and which can stand the test of time. It should be noted that until the last decade of his career (he never formally retired), Plummer generally built the courses he designed.

As an architect who spent considerable amount of time renovating and modernizing other people’s work, Plummer was particularly sensitive to retaining the intent and feel of the original while meeting the objectives of his clients. Westwood Golf Club in Houston, where he redesigned the original nine holes done by Bredemus and added a second nine, is but one good example of the respect he showed his skilled predecessor. (Incidentally, Westwood was totally redesigned in 2004-2005 by Keith Foster, but still retains a Plummer feel, and it is a real sleeper in that golf-rich area).

Plummer was also generous in passing on his knowledge and skills to other designers. He interacted with a number of golf professionals and architects, particularly later in his life. It is said that the late prominent architect Joe Finger learned much from Plummer and credited him for the great success he enjoyed.

Mr. Plummer also felt great responsibility to further the professional aspects of golf architecture. According to the American Society of Golf Course Architects (ASGCA), Plummer became a member in 1956, nine years after its founding. He was given member number 25 (25th member to join), and became the Society’s president for the 1962-1963 term. Unfortunately, the ASGCA’s files are mostly devoid of biographical or career information on Mr. Plummer.

It is a suggestion that the design philosophies Mr. Plummer came to embrace included not only those of Bredemus, but also Maxwell’s, and, derivatively, even MacKenzie’s (Maxwell built the University of Michigan courses and Crystal Down for Dr. MacKenzie, and perhaps assisted with the greens design at Ohio State). Though Plummer greens are often larger than Maxwell’s and not with the same level of internal contouring as MacKenzie’s, he typically designed for faster green speeds. Plummer’s austere approach, his aversion for an over-abundance of hazards, his reliance on natural features to defend the course, and his excellent routings are characteristics often attributed to the aforementioned master designers.

Plummer appeared to be happiest with the creative process in the dirt. Peggy Gunter wrote shortly after her father’s death: “He would wish that everyone could be a lucky as he was to work to the end, making the course a test for the good golfer and a pleasure for the duffer.” A lucky man, indeed, as are those whom have had the pleasure to play his many wonderful courses.

A short list of Mr. Plummer’s best courses in no particular order, all in Texas except for Tryall, follows. A more complete list can be found in the aforementioned, “The Architects of Golf” by Cornish and Whitten.

Plummer Courses

Preston Trail GC (1965), Dallas

Great Southwest GC (1965), Grand Prairie/Arlington

Champions GC- Cypress Creek (1958), Houston

Dallas Athletic Club – Blue Course (1954), Dallas

Dallas Athletic Club- Gold Course (1962), Dallas

Tryall Golf & Beach Club (1958), Montego Bay, Jamaica

Lakeside CC (1952), Houston

Midland CC (1954), Midland

Prestonwood CC- Creek Course (1965), Dallas

Ridglea CC- South Course (1962), Fort Worth

Squaw Creek GC (1971), Fort Worth

Shady Oaks CC (1959), Fort Worth (with Robert Trent Jones and Lawrence Hughes)

Elkins Lake GC (1971), Huntsville

The Shores CC (1979), Rockwall

Tenison Municipal- East Course (1956), Dallas

Pecan Valley Municipal – River Course (1962), Fort Worth

Acknowledgements

This account was pieced together from numerous newspaper and magazine articles, interviews with a few of the architect’s contemporaries, conversations with several golf architects and course superintendents, and the writer’s nearly 30 years playing many of the courses created or renovated by Mr. Plummer.

Byron Nelson and Jackie Burke, Jr., who worked closely with the architect on two outstanding courses, Preston Trail and Champions- Cypress Creek, respectively, provided important first hand accounts.

Marty Leonard, daughter of Colonial CC founder Marvin Leonard assisted with some background information. Ms. Leonard remains associated with Shady Oaks CC, a course also built for her father by Mr. Plummer. Additionally, she manages and operates the wonderful 9-hole Starr Hollow CC in Tolar, Texas.

Ms. Leonard also provided a key introduction to Frances Trimble, noted Houston area golf writer, amateur player, and John Bredemus biographer. An article she wrote for a Nabisco Championships program (unidentified date), “A Man Called ‘Rabbit’ Plummer” was very helpful.

Jeff Brauer, John Colligan, Mike Nuzzo, and Baxter Spann are among the architects who were sought out for assistance. Though all provided interesting and useful insights, a particularly pertinent E-Mail from Mr. Brauer is included in its entirety as an attachment.

Aileen Smith with the American Society of Golf Course Architects was helpful by conducting a search of that organization’s files and providing the picture accompanying this piece, as well as the official dates of Mr. Plummer’s involvement with the ASGCA.

To the aforementioned as well as others not personally cited but who were helpful nonetheless with this simple and incomplete account of a man deserving much more, thank you. LD

Part II by Jeff Brauer

Every large metropolitan area seems to have had a regional Golf Course Architect that does a great job of designing the bulk of the clubs and Public courses that people enjoy daily, even if with less fanfare than the national brand names.

In DFW, from the 1950’s to 1979 that was Ralph Plummer, who designed about 45 new courses in Texas and only 8 in other states. He remodeled 22 Texas courses to only 4 in other states, a remarkably similar ratio, so he was definitely a regional architect!

I have gotten to know his work, through playing and working on many of his projects. As an apprentice with Killian and Nugent, I worked on a master plan for Lake Charles Country Club in Louisiana. My first solo project was renovations to 4 greens at his 1956 Eastern Hills in Garland, TX. Later, I renovated the Great Southwest Golf Club in Grand Prairie (Plummer/Byron Nelson 1965/Brauer 15 Greens, 1991) and to lesser degrees, also worked on a half dozen other Plummer designed courses.

I worked in conjunction with PGA Tour pro Jim Colbert, who taught me how good players think courses should be laid out for the wind, such as canting all targets with the prevailing wind to help set up shots. I noticed that Plummer courses were all designed that way 30 years before! Plummer also had some modern design ideas, like the 6th at Great Southwest Golf Club, which had a sombrero shaped green, with a back tier, similar to an idea that I used often.

Great Southwest has a letter from Bryon Nelson regarding his input to the GSW course design, in which Byron states that he was responsible for many of the Crepe Myrtles at the course, and in green designs, the mounds rolling at the front of the second green were his ideas, based loosely on the 14th at Augusta. GSW and Preston Trail were largely regarded to be the ones on which he assisted Plummer the most.

Preston Trail made a video of Nelson’s memories of how the design evolved there. While the members want to believe that Nelson was the prime mover, he deferred most credit to Plummer, often quoting things Ralph would say, like follow the land in contouring greens (i.e. if the land slopes right, drain the green right) Nelson also notes that he had a fairly straightforward approach, like using smaller greens on shorter approach shots, etc.

Plummer greens appear to have been influenced by Perry Maxwell to me, even with his start under Bredemus. Like Maxwell, most of his green surrounds consisted of one, two or three prominent, roundish mounds’ all integrated into gently rolling surfaces that were a bit less severe than Perry Maxwell’s. This was probably a reflection on the fact that, while he did design or at least tweak all three Texas US Open sites, by and large, his courses were either mid level clubs or public courses, and he designed them for everyday play, usually on a modest budget.

Cornish and Whitten note he was known for estimating cut and fill by eye without detailed plans. While probably true, it’s also true that he built many greens, fairway bunkers and tees in the gently rolling north Texas hillsides with dozers only, moving very little earth, otherwise. At GSW, I can tell there were shallow fairway cuts made on 2, 4, 13, and 18. The rest came from the lakes, or from local hillsides.

Nonetheless, he always built full, bold and natural slopes on his green banks using broad 5 or 6:1 slopes. Later, the trend would be towards steeper slopes to save cuts and fill, and I also noticed he favored (or was forced into for budget reasons) a few holes – 13 at GSW and 7 at Eastern Hills were both reverse slope dogleg lefts, requiring aiming over the rough, and now (if not originally) over some moderate height trees to keep your ball in the fairway. I found those holes great fun and a bit quirky.

My major renovations of Plummer courses were for clubs that felt their course was ‘dated’ and in need of a modern look to attract members rather than a restoration. That would be typical of clubs undertaking renovations of a modest budget course in a bigger money era – More splash was needed.

While I was never commissioned to restore a Plummer course, I had great respect for his designs. Plummer routings rarely can be improved upon other than finding a few new back tees. When remodeling a Plummer green, it was usually possible to lower the putting surface a foot, and produce the necessary fill for any surrounding mounds (At GSW, we only needed to haul to a few greens, like 2) so many of his green sites remain intact, even if the details have changed.

I wish I could have met him, but I moved here two years after he passed away. While I don’t work here as exclusively as he did, and have a way to go to catch Plummer in pure numbers, it would be an honor to someday be thought of as his successor in providing quality local architecture to the DFW area.

The End