Feature Interview with Thad Layton

August 2018

How did you become interested in golf architecture?

While my dad would identify more as an outdoorsman than a golfer, he’d take me out now and again to the local muni in my hometown of Gulfport, Mississippi. I’d beat it around for a few holes and start to lose interest in favor of driving the cart. It wasn’t until a random round with my grandfather in the hills of Tennessee that something clicked. Looking back, I believe my newfound attraction to the game lie in the distinctly different landscape on which this course was situated…the severity of the topography was such a departure from the courses I knew back home, opening my eyes to what a golf course could be. I was hooked.

I came back home with a gifted set of hand-me-down clubs and played or practiced every day, setting my sights on making the high school golf team. While my bid to make the team my freshman year was unsuccessful, this initial failure gave me a singular focus to improve. After redoubling my efforts, I made the team the following year. While competitive golf was appealing, the best part was the access to courses that we’d never played. In addition, my dad was great about taking me to play new courses to feed by growing interest in GCA. In my 15-year-old mind, it was the perfect profession combining three things I loved: sport, the great outdoors, and art.

I subsequently got my hands on a copy of Doak’s Anatomy of Golf Courseand started to appreciate all the thought that goes into designing a worthwhile course. After graduating, I journeyed to Alabama to play golf on scholarship at Mobile University; but I left after one semester for an opportunity to join Ranger Construction in building the new Arnold Palmer course at The Bridges Golf Resort in Bay St. Louis, MS. I was on the ground from the initial clearing to the last sprig of Bermuda hit the ground. After the course opened, I was more rabid than ever in my quest to become a golf course architect, transferring to Mississippi State to pursue my degree in landscape architecture. I badgered my newfound contacts at Palmer Course Design relentlessly for an internship and they gave me a shot in the summer of 1997. That was the beginning of my career at APDC that continues to this day.

In addition to the Anatomy of a Golf Course, what else influenced you? Other books? Particular courses? Certain people?

While at MSU, my affinity for golf course architecture found a sympathetic ear with professor Jim Perry. He helped me convince the head of the landscape architecture department that a trip to the West Coast to study the courses of George Thomas and Alister Mackenzie was a good idea. I got the green light and made a call to Ed Seay, then head of Palmer Course Design, to see if he could make a few introductions for us. The following week my jaw dropped when I received an itinerary from Ed’s secretary that included Cypress Point, Pebble Beach, LACC, Riviera, and Bel Air CC. It was a formative experience that gave me an appreciation for the timeless works of Thomas and Mackenzie – my two favorite architects to this day.

Shortly after signing on full-time with Arnold Palmer Design Company, we were working on a project with fellow Ponte Vedra Beach neighbor, PGA Tour Design Services. Through that collaboration I befriended two other aspiring architects – Brandon Johnson and Joe Walter. It wasn’t long before we were conspiring a trip to Scotland to see where it all started. Through our respective contacts and hand-written letters to clubs throughout Scotland, we cobbled together an itinerary that included 16 rounds in 14 days. While it was impossible to fully appreciate the weight of all we saw, it made me question most of what I’d learned about golf architecture to that point. Courses like Prestwick and The Old Course made me question the unwritten “rules” of golf course design. If blindness and wild contours were verboten in modern golf architecture, why were these features so much damn fun to play?!

What three courses would you most like to see that might help stimulate design ideas?

Of what I’ve seen to date, Royal County Down, Pacific Dunes, and Brora captured my imagination most. County Down for its incorporation of natural land forms to create strategic optics (blindness), Pac Dunes is a master class in modern golf course design – its setting, routing, shaping, strategy, and rugged beauty comprise a golf experience that never fails to inspire, and Brora resonated with me for the opposite reasons as it seemed to be the most raw and least “architected” course I’ve ever experience – 36 spots just level enough on which to tee off and putt-out cloaked in a sea of inexplicable and untouched contours.

Of those I haven’t seen, Shoreacres, Crystal Downs, and Prairie Dunes are on my list of must see courses in North America. Outside of the U.S., there are entire regions (the Australian Sandbelt, the Inner and Outer Hebrides, and the Heathland courses around London) that I’ve yet to explore.

Who are among your favorite authors on the subject of golf course architecture?

When I’m wrestling for the right words to communicate a design idea or process, or just looking for moral support from guys who long ago traveled the road I’m trying to navigate, I find myself reaching for anything penned by Simpson, Hunter, or Mackenzie. Their writing was so vivid, chock-full of the kind of empirical wisdom that could’ve only been gained through years of experience and a healthy sense of humor. I don’t think it’s coincidence that the writing and the courses of that time were as equally full of character. When they can so clearly articulate their thoughts on design, it implies that they know their subject matter intimately. Ultimately the architect needs to communicate his ideas in 2 important ways … to paint the vision to sell the job and to convey this vision along with the technical details to the team executing the work in the field.

How do you define a good golf experience and what do you incorporate in your designs to foster those concepts?

In just one word, I’d say “variety”. A good course is one that never grows stale, no matter how many times you play it. The shots it asks you to hit are always changing due to vagaries in pin location, weather conditions, and your abilities. On the great courses, if you look close enough, there is typically more than one way to get it to the hole.

Variety is one of key design tenets through which we evaluate every design decision. It starts with the routing, where we strive to take the golfer on a journey through all the interesting parts of the property, building context and authenticity along the way. If done right, every design feature then flows from the route as a response to the terrain on which it lies. Mother nature has always been the best design generator and the architect who harnesses those natural features into the strategy gives himself a chance of creating a noteworthy golf course. Sometimes, the landforms just aren’t there and need to be manufactured to insure continuity. That is where the best architects separate themselves from the rest by having an understanding of the geomorphology of the area in which they’re working and the artistry to move massive amounts of earth if necessary to create a landform big enough to look like it has always been there.

Tell us about working with Arnold Palmer. What were his design tenets? How did he influence you?

After our headquarters moved from Ponte Vedra to Orlando in 2006, I got to see and know Mr. Palmer much more.

He was so much fun he was to be around and had this unusual gift to make everyone he met feel like they were the most important person in the room, inspiring loyalty- especially from those who knew him best. While I learned a great deal from him about golf and golf course architecture, the most valuable lessons he modeled were how to treat people and live a life of significance.

He had an approach to golf course architecture but he wasn’t exactly academic about it. It was more something that you saw in his process and learned over years of working with him. Basically, he desired deeply for his courses to be beautiful and fun to play. Within this broad framework, he encouraged his architects to creatively solve the unique challenges inherent in every project, fostering a sense of loyalty and authorship from his team along the way. That is why I think each of our courses is so distinct. While our process and our golf courses continue to evolve, Mr. Palmer’s core principles of fun and beauty are still at the heart of every course we design.

Talk about fun, have you seen Tralee? Thoughts?

Yes, I’ve had the pleasure of playing Tralee. It’s probably the finest canvas on which APDC has ever worked on. The front nine, while quite good by almost anyone’s standards, seems average compared to the majesty of the hulking dunes the back 9 traverses. At 30+ years old it’s a bit of a hidden gem due to its more famous neighbors in SW Ireland (Lahinch and Ballybunion) sucking up most of the available oxygen.

When did the first Arnold Palmer design open – Fifty years ago?!

The first Arnold Palmer Course opened in 1973 in Japan, Manago Country Club. I saw it for the first time last October stopping by for a tour on my way to see 5 of the 13 courses we have in Japan. It was cool to see ground zero of APDC.

How did Palmer and Ed Seay interact? Did you ever see them really disagree?

Having worked together for 4 decades, Ed and Arnold were close. Ed pioneered and perfected the concept of player-branded modern design, creating a frictionless system for Arnold to participate in the process and covering the globe with hundreds of solid golf courses. In turn, Arnold trusted Ed implicitly to run the day to day. There was a palpable level of mutual respect between the two and no, I never saw them disagree about any design issues in the field. I think the fact that APDC is still going strong in their absence speaks to the solid foundation on which they built the company.

One thing I’ll miss most about Ed and Arnold- they knew how to make site visits fun, ratcheting up the energy levels wherever they went.

Palmer was a true world traveler. Did he ever mention courses that he especially liked and/or ask you to emulate certain features from a course?

I always enjoyed asking Mr. Palmer about the courses he liked playing most. He’d light up recalling the drive he and his dad regularly made over to play Pine Valley around Thanksgiving and how he relished the challenge of breaking par there. On Cypress Point, he said it was a beautiful course, but didn’t like how it took driver out of his hands. On one occasion, I remarked how much fun the greens at Augusta must be to putt and he quickly let me know that playing tournament golf on those greens was anything but “fun”. While he doggedly loved Augusta, he cautioned against creating contours on that scale on any of our work.

What course that you designed with him are you most proud of?

AP was always passionate about growing the game. As one of his younger architects, I seemed to get some of the more remote assignments. Brazil, Uruguay, and Kazakhstan are some locations where I had the honor of helping place the first Arnold Palmer flag in that country.

My very first job as lead architect came in 2004. This responsibility came a bit earlier than I expected and might have had something to do with the project’s remote location- Kazakhstan. But this was the opportunity to prove myself and I grabbed it by the horns. On my first trip there, after deplaning in Almaty, a small army greeted us with machine guns and I knew that this was going to be different. Our man on the ground, Ian Gannon, collected us at the airport and shared some bad news with us on the way to the job site. Our lead shaper had been turned away at customs and of the 8 WWII-era dozers on site, only two of them were operational. Importing supplies and finding local labor proved to be equally challenging but the team persisted and we put together Kazakhstan’s first 18-hole course that would later go on to be the perennial host of a European Challenge Tour event. I look back and laugh about all I thought I knew back then and what I learned from that experience.

The course I’m most proud of would be Fazenda Boa Vista … it was a turning point for me and when I felt like I found my groove. The land had potential and holes on the front nine were routed down low along the Sorocaba River and the back nine ascended over 200 feet into steep foothills. I spent over 100 days on site working with the team of Pro Golf Brasil led by my friend Antonio Miranda to put together a beautiful set of greens complexes that blend seamlessly into the landscape. The bunkers were works of art executed by Jeff Stein and finished by Brett Hochstein. Strategic width and slope combined with a fast and firm maintenance regime provide an inland links feel. Environmentally, we preserved native pasture grasses throughout the course that provided contrast and required no irrigation. I’ve played it a few times now and have to say its one of the most fun courses we’ve ever built.

I think the course is an exemplary model of the quality of golf that can be achieved when you have ample corridors and stands as a testament to how we’ve gotten better by moving closer to the design-build model.

Arnold Palmer saw the game change before his eyes at the annual Bay Hill tournament. Players drive it eighty yards farther and 7 irons fly 200 yards at sea level. What did he think – did he feel equipment had gotten out of hand?

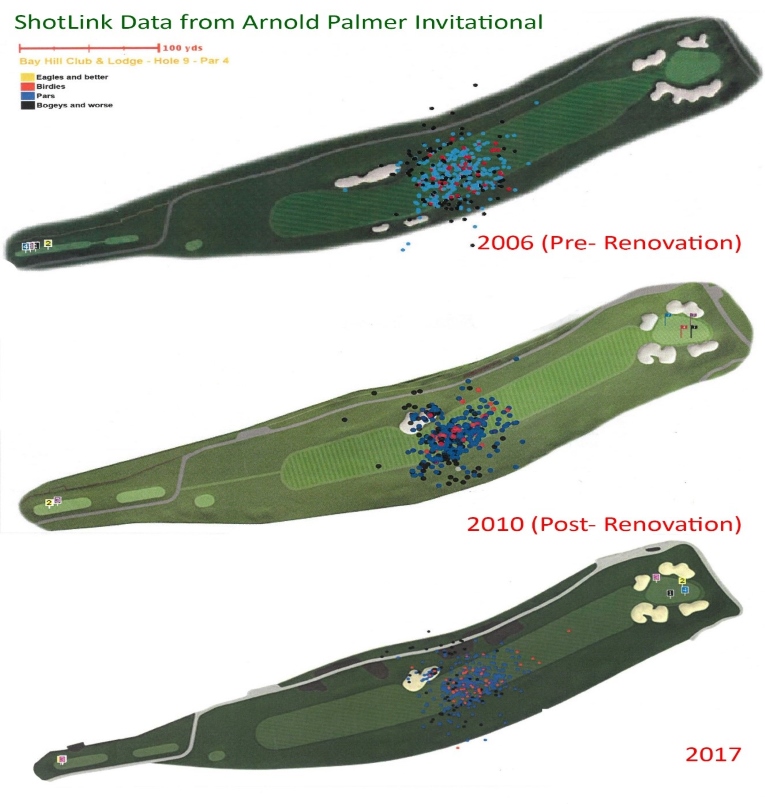

He was an advocate for rolling back the ball for as long as I can remember and having a front row seat to watch Bay Hill get progressively overpowered certainly didn’t help matters. When we put Bay Hill under the knife in 2009, we used the PGA Tour’s ShotLink data extensively to inform our decisions. For instance, when we studied the 9thhole it was clear from the shot patterns that the bunker inside left was just window dressing as a carry of only 255 yards. So, we flipped the bunker end over end, pushing the carry to 285. Curious to see how things worked out, we reviewed the data post-tournament and saw some interesting patterns emerge. It was clear that this new bunker was now in play and there were far fewer players air-mailing the bunker. However,the more interesting statistic was the new shot pattern that emerged, play had been nudged further right, bringing the right rough more into play and setting up a more difficult angle from which to attack the green. But, it wasn’t long before the new bunker was rendered irrelevant by most of the field and the old cluster towards the center of the fairway returned. If AP would have seen Rory hit lob wedge into the green last year after roasting it 383 off the tee (that’s his red dot on the bottom graphic), we’d be looking for space to add distance!

Shotlink Data from Bay Hill showing every shot over 4 days on the 470 yd par four #9 at the Arnold Palmer Invitational.

It’s hard to imagine there are many left in the industry recalcitrant enough not to recognize that something must be done about distance. Popular opinion seems to be coalescing around rolling the ball back uniformly. Of all the options, it seems to be the easiest and most impactful thing to do. My rule of thumb is that if you can’t see the ball land, you’re no longer playing golf.

What is a sleeper hole at Bay Hill that you really like that a viewer on television might not fully appreciate?

Usually it’s the holes on the back nine at Bay Hill that get the most attention during a golf telecast but I prefer the front. Holes 3, 5, 6, and 8 are some of my favorites on the course and of those, the par four #3 is perhaps the least seen or appreciated. It is, by definition, a Cape hole and hugs the opposite shoreline of the same circular lake that guards the infamous par five #6. The elevated tee clearly lays out the task at hand – challenge the lake on the left to set up an easier approach or avoid the issue and deal with the water on your second shot. This pay me now or pay me later scenario is a hallmark of Bay Hill and contributes to its reputation as one of the hardest starts on Tour. One other interesting fact that might surprise you about Bay Hill is that there is over 40 feet of elevation change from top to bottom.

Future plans for the company?

In the wake of AP’s passing, there were more than a few folks that wanted to write us off. Our message to our clients then and now is simple – we’re not going anywhere. Mr. Palmer left us in a very strong position with a legacy of nearly 300 successful courses that value the Arnold Palmer Design Company brand, a brand we’re uniquely qualified to curate. Furthermore, we’re doing some of the best work we’ve ever done. Just like Arnold Palmer who stayed relevant throughout his entire career by trying to get better than the day before, we have the same philosophy of never-ending improvement. There have been examples in other industries of the brand outliving its founder and if we’re doing great work that embodies the principles of our founder, there’s no reason that we cannot repeat the successes of other industries in the realm of golf course architecture. The brand remains strong and we see golf course design as an integral part of perpetuating Mr. Palmer’s legacy by continuing to create great courses that bear his philosophy and his name.

Since opportunities for new designs are quite limited and many architects have turned to restoration/redesign. what are your thoughts about that process.

Most of our current work consists of remodels and renovations. While typically more difficult than building new, redesigns can be more rewarding because of the new life they breathe into a membership and a community. While there are a handful of new courses being built on some epic sites around the globe, how many more of these can the retail golf market sustain? Don’t get me wrong, while we’d love our chance to show the world what we could build on a big pile of sand near the ocean, we think the most fertile opportunities to grow the game exist closer to home. Rebooting tired courses in urban areas with quality golf course architecture will undoubtedly provide the most benefit for the greatest number. Everyone deserves access to well thought out strategic design and it certainly doesn’t cost anymore to build!

Our most recent work at The Royal Golf Club is a good example of what can be achieved by reinvesting and revitalizing struggling urban courses. Developer Hollis Cavner brought us in to work together with Annika Sorenstam in reconfiguring the old 3M Tartan Park Golf Course into a better 18-hole version of the previous 27-hole complex. We re-routed parts of the course, removed loads of non-native trees, stripped down the sand area to just 23 bunkers in total, added scores of strategic width, and re-contoured all the green complexes. The course improvements were funded by converting the additional acreage into developable land and the course has experienced a renaissance in the local community.

Recycled railroad ties support the bunker face on the steep sloped approach to the par 5 second at Royal Golf Club, St. Paul, MN

Only 23 bunkers! Nice – the Huntercombe of the Mid-West! Where do you think bunkering is superfluous in modern architecture?

In golf course architecture as with any other creative endeavor, knowing what not to do is just as important as knowing what todo. One of my favorite quotes that captures this concept is from Antoine de Saint Exupéry- “It seems that perfection is attained not when there is nothing more to add, but when there is nothing more to remove.” In a culture that increasingly despises over the top displays of conspicuous consumption and waste, the virtuous implications of addition by subtraction ring true. Every feature on a golf course, especially bunkers, must justify its existence or it doesn’t make the cut.

There are still plenty of courses that could undergo a significant reduction in overall bunker square footage and emerge on the other side a much more interesting and financially sustainable golf course. Not coincidentally, this is a large part of the scope of many of our current master planning work. I can’t think of a single renovation we’ve done in the past decade where we didn’t end up with less bunkering than when we started.

What has been the feedback? I presume that maintenance savings and quicker rounds have resulted?

At the Royal Golf Club, we considered the moderate maintenance budget, the client’s goals of a family friendly course, and the natural bold topography of the site that could serve as its own type of hazard. Ultimately, we resolved that bunkering was a feature we’d only employ as a last resort, relying instead on contours and masses of native fescue grasses. The bunkers we did build, however, refuse to be ignored; most of them nudging dangerously close to the centerline. The feedback indicates people are enjoying the course and getting around in less time than before. So far, no-one has complained that there aren’t enough bunkers.

What is your approach to renovation? Is your philosophy to renovation different on courses that aren’t Palmer designs?

When faced with course disruptions from the inevitable replacement of infrastructure, there is a decision point: Put things back as they were or seize the opportunity to improve, rearranging the dirt in a more interesting position before re-grassing. Statistically speaking, most of our previous clients want things restored to a certain degree while new clients seeking our remodel services want us to take their course in an entirely new direction. When clients see the incremental costs of improvement, they typically choose the latter path.

Naples Lakes CC, could be best described as a “restovation”. We preserved the best qualities of one of our past designs while improving other elements of the course, making a good course even better.

On the other end of that continuum, we’ve taken courses that aren’t our original designs and transformed them enough to call them our own. Our most recent large-scale remodel was a home game, 5 miles from our Orlando offices, Shingle Creek. We rerouted the course to make room for a hotel expansion, added 3 new holes, reshaped all of the greens complexes, and reduced the bunker area by over one third.

How have you evolved to the design build model?

You’d have to be in denial not to recognize that almost every course of significance built in the past two decades has been executed with some variation of design-build. Back in 2007 when I saw Bill Coore bouncing around the Sugarloaf Mountain site on a sand pro, I thought wow, here is one of the legends in our business personally finishing his own greens … in his sixties! Right then and there I decided to learn how to run equipment.

At its highest level, golf course architecture is sculpture, not drawing. While there is a time and place for thoughtful planning, detailed drawings and specifications, there is also a time to put the drawings aside and get in the dirt to take it to the next level. Like McLuhan’s theory,“the medium is the message,” drawings can become the message or put another way, an end instead of a means to an end. An overemphasis on drawings limits your ability to respond imaginatively to the challenges and opportunities on-site because your mind is trapped to all the sunk costs you’ve made on paper. Clients may pay for tidy drawings, but in the end, no-one plays the drawings.

The transition toward design build is the biggest change at Arnold Palmer Design Company over the past decade and one that, I think, would surprise most people. My typical time on-site now averages around 100 days. I can run just about any piece of equipment and feel comfortable enough on a dozer to perform some of the work when necessary. More importantly, we’ve been bringing on proven talent to help implement our work and contribute to the field design process. Like the music industry where collaborations create fresh new sounds, we’ve found that partnering with other shaping specialists leads us down new pathways, yielding a better product.

What style bunkering do you favor?

Whatever best fits the site and the financial/maintenance realities of the golf course. I’ll admit that I’m predisposed to a meandering, broken bunker edge but that look isn’t for every property. After all, what would NGLA be without its steep grass faces and flat bottoms, Royal County Down without its fescue fringed edges, or St. Andrews without its iconic accordion-like revetment bunkering? In the end, it’s all about context.

Green styles?

While I’m starting to mellow a bit, I still find myself erring on the side of too much vs not enough on the spectrum of green contour. If you don’t have the occasional complaint about your greens, they’re probably boring. I’m of the opinion that contours should affect strategy and shot selection, therefore slopes must be legible from where your hitting the approach. The Redan or Biarritz are obvious examples how contour influences shot selection. Even for those playing the course for the first time the strategy is clear – and that’s why I think they work so well. In the modern era where green speeds erroneously equate quality, the challenge is to build greens that effect strategy without going over the top.

I’ve heard Mr. Coore talk about “effective green speed”, meaning the combination of speed and slope, as a more wholistic measure of green speeds than stimpmeter readings. If you can get buy-in from the client and superintendent on the front end of a project to this concept of “effective speed” you set yourself up for a more interesting set of greens and simultaneously take pressure off the superintendent, the turf, and the maintenance budget. A well-contoured set of greens rolling at a 10 will give you all of the interest and challenge you need.

That’s a great point. What about green size? Some of the great places in golf like Pebble Beach and Prairie Dunes thrive with greens that are 4,000 square feet or less but no one seems to build them anymore. Do you see many opportunities to build such greens? ( like the terrific new ninth you did at Bay Hill’s Charger nine).

I tend to agree that most new courses have greens that are comparatively large to the ones you mentioned. I suspect this can be traced back to the advent of the Stimpmeter, golf course superintendents seeking a cushion to spread traffic and reduce turf stress, and the ratings game that eliminates restraint from the toolkit of architects trying to capture the imagination of raters with ever bolder contours.

So yes, building 18 small, subtly contoured greens would probably be the most counter cultural thing an architect could do these days … but then again Mr. Dye made a career out of small greens and going against the grain.

Measuring less than 100 yards, the sub-2000 sf 8th green at Las Piedras creates an illusory target. The power of a small, subtly shaped green shouldn’t be overlooked!

What are some overrated features that you wish developers/architects would move away from?

As Mark Twain said, “When you find yourself on the side of the majority, it’s time to pause and reflect”. With that in mind, I’ll be the contrarian on the latest craze in our industry – WIDTH! While I’m an advocate of the strategy and fun that width can stimulate, the deafening chorus in favor of unfettered width has made me rethink its wholesale application. The spate of new destination courses appears to be in an arms race over who can go widest. I’ve played a few of them now and cannot get over the sensation that I’m consuming empty calories. Where is the variety when every hole is 70 yards wide? Where is the interest when you can indiscriminately send driver on every hole without worrying about anything more than a compromised angle or distance?

At the highest level accuracy off the tee under pressure matters when identifying the best players. Even at the club level, placing a premium on getting one in the fairway may require clubbing down and leaving a longer second shot. I think of this carry depth as the “longitude” to the “latitude” of horizontal width. Say what you will about Pete Dye courses, they have loads of strategy within the confines of their relative narrowness. When it comes to width, I think we’ve reached the tipping point and it will be interesting to see where the industry goes from here. If there’s anything for sure in this business, it is that tastes will continue to evolve.

Why should someone hire you?

I’d simply ask someone who hasn’t seen any of our recent work to just go out and play something we’ve done in the past 5-7 years and ask yourself one thing: Did you have fun?