Pete Dye’s influence is frequently cited on many great architects of today, including Doak, Coore, Liddy and Whitman. Yet, at age 30, you are of a different generation. Who have been your primary influences (and perhaps Dye is indeed one of them)?

That’s a good question that operates on two separate levels. If someone were hiring me as their architect I’d like to think I have a personal style that is entirely that of my own. I’ve never been much of a conformist anyhow, but if their is one singular thing that Tom Doak impressed upon me it is if you want to be a great architect you had better find your own path. That’s always left an indelible mark. And I think that speaks volumes to my influences right there.

Tom’s impact on me as a mentor, friend, along with his approach to architecture, and his practicality casts a long shadow. Part of the reason I wanted to go into the design and construction business was the fact that he, as well as Bill and Ben’s work though the 1990’s perfectly paralleled and expanded upon my own fascination in classical architecture. I would have considered all three of them heroes going into the business and it has been a great experience to have worked for all three of them since. But I would be quite remiss in neglecting to mention I’ve taken something away from all the architects I’ve worked for and learned something from all of them. And of course with that, all of the new wave/left of the dial work in the last 20 years. But Tom above all others.

As much as anything however today, my year overseas studying golf courses in the UK has become arguable my main influence. As for the Golden Age its easy to name off the usual ten architects and writings, but I’m particularly fascinated with some of the ideals of Thomas, as well as Ross late in his career — and countless other nameless faceless souls we’ll never know in early golf in the British Isles. A little MacKenzie as well.

As a shaper and finisher day to day, I’m of course influenced by all the above entities as well as anything and everything interesting one might steal from mother nature. Now I don’t want this to dribble off into a list of influences that sounds like a ridiculous rendition of Cuba Gooding Jr’s Oscar speech a few years ago where I list off everyone from my high school drafting teacher, to Jimi Hendrix, and the Marx Brothers! But in addition to the architects I couldn’t possibly neglect to mention the many shapers, design associates, and finishers I’ve worked with. I have certainly learned a lot from these gentlemen within the creative spirit of these projects. I think we’ve all learned from each other the last 10 years. Not to mention their are a number of entertaining characters in this list. Hopefully I’m not forgetting anyone but the list includes Will Smith, George Waters, Dan Proctor, Dave Axland, Jim Wagner, Patrick Montgomery, Don Placek, Eric Iverson, Mark Thawley, Brian Ceasar, Kye Goalby, Phillipe Binette, Bruce Hepner, Jim Urbina, Brian Schnieder, Brian Slawnik, Jack Dredla, Ron Ferris, Josh Smith, Brian Ackinson, Jeremy Miller, Jason MacCarthy, John Kemp, Toby Cobb, and Shaymus Mayley.

Talk to us about shaping as it is such a broad term. What is it exactly and what is meant by tying features together?

Shaping is indeed a broad term. If you truly love architecture then you truly love the day to day process in the field of design and construction. And if you do, there are few things more exhilarating as being out in the field as a part of the progression — whether it be at a place as awe-inspiring as Cabot Links, or as simple as rolling farm land outside Philadelphia. In my case depending on the project a day is likely to include bunker, green, fairway, and tee building, and/or some project management, layout and planning, time going over upcoming work with the architect, occasional map work, and bunker/greens finish detailing. In the end, it’s all the same game — getting the absolute most out of each and every detail of the hole and maximizing the architect’s concept.

Tying features together is a catch all that can mean a number of different things in the shaping and design repertoire from mass grading down to finish. One could write a book on it — especially tying features in and out of greens complexes and how it effects every facet of strategy and recovery. A great example is the 7th green at Pacific Dunes which includes a number of ways to tie features together in one green complex alone. The large mound at the back center of the green is connected to the dunes left of the green by a low ridge, creating an exacting back left pin. Front left pins sit precariously close to slopes leading out of the front left bunkers into the green. That’s just two good examples.

Another interesting idea of feature tie-in is the concept of visually tying bunkers together for deceptive purposes — in other words making two or more bunkers spaced well apart appear as though they are same bunker. One good example of this is the par 3 8th at the Dukes Course in St Andrews. In the photo below you see what appears to be one large bunker stretching across the entire right half of the approach. In reality they are actually three entirely separate bunkers spanned out across 60 yards — but shaped precisely to appear as one bunker from the tees. In addition, the horizon line of the middle bunker performs the old trick of blocking the ground behind it. Thus it appears far closer to the green than it actually is — in this case there is some 30 yards between it and the green even though it appears to be less than 10 yards from the tee. In actuality, only one of the three bunkers is near the green. The net result couldn’t be more in line with MacKenzie’s theory of making holes look harder than they actually are.

The 8th at the Dukes Course. From the tees a long spiraling bunker appears to engulf the entire right approach up to the green. (Photo by Phillippe Binette)

In reality it is a only one greenside bunker and two relatively unassuming short bunkers shaped and arranged to visually accost and confuse the first time player. (Photo by Tim Liddy)

Another good off kilter example is the swale feature aiding the third shot to the far right hole location on the wild par 5 twelfth at the Prairie Club (Dunes Course). The far right pin location is on a ridge — and it’s a shallow one at that — fronted by a long, funneling, swale. In approaching on the third shot, throwing a wedge shot up in a stiff crosswind and going over the green is no good. Losing it right into the steep slope of native or bunker is even worse. You aren’t getting up and down from there! And there are plenty of gale force days out there like that. So clearly there is a covert advantage for the player who can play low and miss short. There is one place in the fairway he can lay up on the second shot and give himself a perfect view up the swale to this hole location and see everything in front of him as shown below. From there, he can use the funneling nature of the swale by hitting a lower skipping shot up the slot to sweep the ball up to the hole — keeping it out of the wind and out of harms way. If he misses his spot on the lay up, he will have to reconsider his options and play a more low percentage shot if he wants to make 4 or 5.

Prairie Club #12- From the second shot at the top of the hill the players blast off into the wide abyss of an 80 yard wide fairway on the left to set up his third to the back right pin. This is clear. But much like other great ultra wide fairways that lull players into a lazy lay up, the intelligent player that finds the right spot has the advantage in all conditions. (Photo by Peter Wong) -If you are curious to see more of Peter’s fantastic photography out there it can be found here http://www.peterwongphotography.com/courses.aspx?gallery=the_prairie_club.aspx

Close up of the 12th at the Prairie Club. If he succeeds he has a clean view and perfect half pipe to skip a ball up the swale to the back right pins under the wind — or the shot of his choosing. This feature also helps visibility over the entire spectrum of hole locations (Photo courtesy of Ross Buckendahl)

Part of this approach and swale was natural but most of it was painstakingly shaped and arranged. Building these kinds of features requires patience and trial and error — or trying something else if it’s not working.

One last great example I can’t help but include is the approach to the par 5 12th at Pacific Dunes, a great hole often overlooked despite the fact it features one of the courses best subtle features. A low ridge runs the entire length of the approach and into the green and effects approach shots of all shapes and sizes. If you are going for the green in two it can act as a kicker curling balls towards the left hole locations behind a gaping front bunker…

On the other side of the ledger, it can serve as subtly vexing hazard that deflects shots offline away from front pins and thus requires thought in the precise location of the lay up. Those are great basic examples of tying features together, though it only scratches the surface. It’s worth noting that one hole I was fortunate to have worked on includes all 6 kinds of the examples above and that’s the 4th at the Prairie Club.

From a shaper’s perspective, what are the advantages of working in sand?

Obviously heavy soils limit what can be built effectively because of its effects on turf speed, drainage and soil structure. So with that in mind, shaping in sand allows far more freedom to build interesting features both from the aesthetics and play standpoint. That leads to the crucial advantage of shaping in sand — it gives us a whole new conceptual palette to build more features that encourage the ground game and interesting recovery play!

Naturally sandy sites are always the easiest to describe. But the true value of sand is far more striking when describing holes like the 1st and 17th at California Golf Club. The property’s natural soils are heavy clay. As part of the overall concept of the 2007 renovation Kyle Phillips proposed to sand cap the holes to encourage the ground game throughout the course. It was a bold move and it is part of the reason Kyle endeared himself to the membership. In addition, a considerable amount of re-grading was proposed to restore holes lost in the 50’s. This combination ultimately led to the 1st and 17th becoming two of most successful holes on the course for interesting ground play. The 17th’s original green was small and propped up on a relatively abrupt hillside plateau with minimal opportunity to run shots onto its tiny green — not really that exciting for a 560 yard downhill/downwind par 5. Kyle typically did a green sketch to give us a jumping off point. Since we didn’t have one in this case, I thought it might be worth experimenting a little bit to make it a little more ground game friendly. I lowered the green by 1 1/2 feet and using the excess material, created a more running shot friendly approach, that would kick faded second shots onto the green — to see if Kyle liked it. This gave players the opportunity to ride Cal Club’s legendary southwest wind onto the green. The shapes I roughed in for the green would also encourage the new-found ground elements in shorter third shots. Kyle wound up liking the experiment and it eventually became the version we see today. Now without the sand cap, it would never have occurred to me to experiment with the green site in this manner but with firm and fast conditions, it was more than worth the experiment.

On the other side of the course, in a completely different light, the wild first green and approach Kyle Phillips and shaper George Waters cooked up wouldn’t have been nearly as exacting and traumatizing if it weren’t for the sand cap induced turf speed. Failure to negotiate it is sure to send some Cal Club member across the fence to the Buri Buri Liquor store sometime in the next 50 years. Maybe the proximity to the liquor store explains George’s infamous wild indiscretions with the depth of that back bunker to begin with?

You have seen Bill Coore, Tom Doak and Tim Liddy at work in the field. How do their approaches differ? How are they similar?

That’s a tough question as you happened to choose the three that approach their work most similarly of all I have worked for. I would have liked to have hung around during the routing process of Streamsong with Tom and Bill for my own curiosity on how they approach routing as part of the big picture of a multi-course project.

First and foremost, they are field oriented architects who strive for excellence in every level of their results. It would surprise no one that they spend a tremendous amount of time in the field walking and analyzing developing ideas. In addition to their obvious decision making skills, they are excellent teachers and communicators — whether it be with the client or crew. They spend a considerable amount of time walking the site developing the routing, developing hole concepts, flagging possible hazard locations and working with the construction personnel. To maximize their concepts and results, they build teams around well studied design associates, shapers, and finishers they know and trust. All three work in the field through the construction process, and make adjustments as needed. Once they are happy with the results, they sign off personally on the completed holes for grassing.

If I were a betting man, which I am, I would guess Tom’s approach to the design and work is heavily influenced by MacKenzie’s from eighty years ago. His goal is to make his time on site efficient while getting what he wants out of the design. Tom’s prioritizing of routing, hole and aesthetic concepts, and major green construction makes him efficient and allows him to focus on what he needs to without obsessing over certain aspects that he trusts his guys will get right.

He doesn’t use sketches. He works the greensites in the field. Sometimes he starts with a specific concept in mind. Other times he experiments in the field or lets his shapers run with an idea if they have something in mind. But obviously he always acts as editor giving final approval to the exact details to keep the big picture oriented the way he wants it. And one thing that is consistent with Tom, is that he is always guaranteed to spend a tremendous amount of his on site time with the greens construction. In addition he is very encouraging and likes to let field personnel have some fun and be creative. Tom likes to keep things fresh, efficient, and fun in this regard. Though he seldom has time with the rigors of multiple projects, Tom does get on the dozer to shape from time to time. There aren’t many architects who do that!

Bill is similar but also has certain differences. One thing of interest in this regard, is Bill handles the final preparation of the greens for seeding himself. He is the only architect I’ve ever been associated with that does this. I think he loves dabbling in the detailing and finish work process. It is just part of how he likes to approach the work and his attention to detail.

Tim is similar but perhaps a shade more plan oriented. But only by a fraction. He likes to walk and stick to where the action is as well and make adjustments as he feels they are needed. Hence shaper Brian Ceasar’s nickname for him, The Grey Squirrel. But ultimately his approach is similar to Bill and Tom’s.

Everyone talks about the importance of the architect ‘being in the field’ and ‘doing work by hand.’ What are three specific examples where you have seen this make a huge difference?

I can think of so many great examples on all levels whether it be architects, associates, shapers, or finishers. It’s hard limiting it to three precise circumstances. So I’ll reference examples in five major phases of the design process.

Routing – Pacific Dunes – Every great routing is the product of careful work on the map and great field analysis and adjustments. The final routing of Pacific Dunes is a prime example. As a memento from the project, I kept a map of an alternate routing Tom did shortly before the final version we see today.

Needless to say the pre-existing version was awfully good in its own right having been weeded out among several other candidates. I must have spent hours bored in class at Oregon State trying to figure out why Tom continued pursuing different possibilities beyond it! But in the end he found a better final solution because of spending time in the field and knowing every inch of the property. That’s always served as a distinct inspiration to me as to the importance of patience in the routing process and time on the ground. It’s a great lesson for any aspiring architect. The difference between decent and good is a lot smaller than the difference between good and great!

Grading phase – California Golf Club – When done right the mass grading plan is the second leg to a great golf course. If you have a bad routing, poor mass grading with no field adjustments means that you can probably give up on the course right there. Kyle Phillips overall grading plan for Cal Club was both ambitious in its sweep and excellent in concept and final results. It restored a number of the large swale features on the course that had been lost when the original course was changed to accommodate a road in the 1950’s. Kyle and his associate Mark Thawley made several adjustments along the way that worked to the best solutions possible. There are great examples throughout from the entirely created 2nd, 3rd, 4th, 7th, and 8th holes and critical adjustments on several others.

Greens, bunker layout, and the construction phase – Since this is where the golf begins to take shape on the micro scale, I could think of dozens of worthy examples but I will stick to just one from the Prairie Club. I don’t remember who it was — Tom Lehman or Chris Brands — that made the decision mid way through the construction to expand the back edge of the par 3 16th green at the Prairie Club another 20 yards but it was a great call. The adjustment included a low wind eroded swale and created a semi-biarritz style back third of the green creating a number of interesting hole locations in the process. In addition to the front and back biarritz aspects, it also creates a narrow hole location just to the right of the swale. The plateau that the green was initially meant to sit on was an excellent hole on its own and was already quite large. Conversely building a normal size green around the swale alone would not have been altogether practical as every pin on any given day would have been rather difficult. So it was far from an obvious decision to consider including the swale as green. The net result of those changes, the green’s other pins, supported by a rambling 90 yard long “cattle trail” bunker is nothing less than arguably the best par 3 on any course I’ve worked on. Trust me, you haven’t seen this hole anywhere else before!

Honourable Mention- Tie, all the holes through the flat of the property at Pacific Dunes — #12, #3, #15, #4

Finish and Grow in – The entire restoration of the Pinehurst #2 is a great example. It’s essentially an open essay on the detailing of a golf course in the field. But I’d like to point out Bandon Trails because I think Coore and Crensahaw original work is the way to appreciate Bill’s and Ben’s meticulous attention to detail. In the weeks leading up to the opening of a 7 hole preview loop for resort guests I was sent to work on the final bunker detailing. I assumed they were just going to have Jeff Bradley and I do some hand edging and preparation for play. But that was hardly the case. On the 18th hole alone Bill had me add two bunkers and before it was all said and done, Jeff and I had made noteworthy changes to most of the bunkers on the hole. He had me add a new bunker and sandy area on #2 as well. In the end, of that seven hole loop roughly a quarter of the bunkers were altered in some sort of substantial, interesting way.

Clearing Phase and Hole Concepts – We have all heard what a monumental task routing the Sand Hills Golf Club was down to 18 holes within thousands of acres. That must have been some kind of mind bender because just figuring out the grassing arrangements of the 18 holes at the Prairie Club was laborious enough.The Dunes Course features what might be the most perfectly contoured Nebraskan Sand Hills ground for golf one can imagine. So much like Bill and Ben 15 years prior, Chris Brands and Tom Lehman had quite a task isolating the best 18 holes. After over a year of hard work in the field, Tom and Chris finalized the routing three weeks before construction and I was sent out to begin mowing the basic outlines of the holes they had on paper. I have to say the mowing process was one of the most enjoyable of my career — every hole had a multitude of features, possible angles, and natural details that were worth considering in the final versions of the holes. So with that in mind I just mowed around everything interesting I found and from that point they began editing and expanding the final margins of the holes over several months. It is a great testament to the quality of the Tom and Chris’s routing and the quality of the landforms, how difficult that editing was on that scale. Where do you stop? In that process, many great decisions came to fruition on the many possible hole arrangements, from the 17 at The National Golf Links of America inspired elements of the par 4 13th, to the — dribble off the plank to position A. tee shot on the 6th — to the back door alternate fairway on the drivable 11th. These are just a couple of countless examples of the field adjustments leading to tremendous options in how the holes play. Some of those major additions like the alternate second landing area on the 12th didn’t come into the picture until the very day Chris and I hammered in the final stakes for irrigation. Some of the smallest pre-existing natural details that came to light during the mowing process wound up being focal points on the hole’s strategies such as the bathtub sized blowout bunker in 12th fairway. Tom and Chris had always encouraged all of us to contribute ideas as part of a team effort and it made the process a lot of fun — and all did indeed contribute. But in the end, Chris and Tom had a monumental task to make final calls to create the best holes possible when the ground would have allowed a number of interesting arrangements. They can’t be commended enough for the time and effort they spent in the field to make that happen. Many of the best elements in the design are the kind that wouldn’t have shown up on a map and would have been missed by 95% of architects before being plowed under by a construction contractor.

Bandon Trails doesn’t have cliffside holes à la the other three courses at Bandon. And yet, it has attracted a very loyal following of admirers. Why do you think it works so well?

For starters, I think it possesses not only two of the resort’s very best holes in the 4th and 5th, but two of the twenty or so best holes of Bill and Ben’s remarkable career. If that’s not enough to get people’s attention I don’t know what is! In addition, it possesses a number of great supporting holes and a couple that are sure to make a short list of Bill and Ben’s most photogenic as well — 2, 5, 14, and 17 just to name a few. And it’s in the aesthetics where I think it really captures people. I’ve always been impressed that the land and vegetation away from the ocean in Bandon has such a depth of fascinating micro-environments. In the case of Trails the combination of Dunes/Beachgrass, Manzanita/Kinnickinick/Evergreens, and native Rhododendron/Evergreens is an amazing blend of plantscapes that the routing meticulously winds through. As Dave Axland is quick to point out, it is still the most varied plantscape Bill and Ben have worked in to date and it makes for tremendous variety of holes to the routing. Much like Pacific Dunes, I think that is a huge part of its success and cannot be overstated.

And for the hardcore architecture student it’s a very interesting look into how Bill and Ben’s style has evolved. In the ten years between Sand Hills and Bandon Trails, a lot happened there. To me Sand Hills is in many ways the 90’s greatest example of great art coupled with brilliantly textbook strategic simplicity — diagonal hazards, etc. With the details of holes like 1,3,4,6,8,11, and 12 to name a few, in many ways Bandon Trails is one of the 2000’s most progressive and greatest achievements in subtly and restraint that requires an even deeper level of careful study. If you know your Beatles history, and you were comparing Bill and Ben to the Beatles, which is an easy comparison, then Sand Hills would certainly be the album Revolver, Friars Head Sergeant Pepper, and Bandon Trails would be the White Album.

What is the best raw site that you have ever worked on? How about seen?

There are 4-5 sites I’ve looked at the last few years that would fit in the category. One in particularly myself and a couple associates were trying to get off the ground. But the fall of the plastic empire took care of that!

All in all, Pacific Dunes is pretty hard to beat. In addition to the obvious aspects of the craggy, misty Oregonian coastline and almost perfect contour, the mix of colors in the vegetation and dunescape is still startling – and I grew up in Oregon! That is all obvious to the golfing public, but few people who visit realize just what an incredible stroke of luck it is that Bandon’s property was available in this day and age on that coast. Further it can’t be overstated how many environmental land mines could have been lurking that would have prevented the projects from happening. Tom’s routing shows that diversity in the remarkable sequence as the first six holes pass through six completely different micro environments. And for as long as I live, I will never forget the first time I saw the land that would become 13. It’s just simply a near perfect site!

Barnbougle was also clearly pretty remarkable in its own right — ocean, river, estuary, swamp, tremendous over water views up and down the coast and into the surrounding hills toward town. When you throw the whole package of small, mid, and large scale contour together, Barnbougle’s back nine is the best section of any property I’ve been around.

Tell us about the pros and cons of The Dukes Course at St. Andrews.

Obviously, there is no place like St. Andrews. It’s a wonderful little place beyond its omnipresent golfing status and it is a unique historical center and university village. I found it even more so having lived there just long enough to enjoy it as part of the community and not just as a visitor. With that, The Dukes’s location has a nice interaction with the village with its hilltop views toward the town, and its long range views across St. Andrews Bay toward Carnoustie and the Montrose Coast. Its also a beautiful piece of Scotttish upland with its quarryed, mid-property drop step, streams, and mix of Scotch Pine and hardwoods. In addition, the Old Mount Melvile House and Craigtoun Manor give it the best neighborhood backdrops of any project I’ve been on. The original Peter Tompson design was a fairly generic 1990’s era faux links that just didn’t fit the property. Tim Liddy was retained to give it a style more reflective of the landscape. He chose a really nice concept in re-routing the awkward closing holes and tried to give the course more of a heathland flavor with Colt/Simpson-esque bunkering. He removed as many of the offending faux-dunes features as possible. The results of the renovation include some of my favorite bunkering on any course in my career and made the overall landscape become more believable as an old Quarry and low rolling sandy heath. During the 2005 construction and since, Tim built new greens on the 1st, 9th 13th, 14th, 15th, 16th, 17th and 18th. The style of renovated greens complexes works well in it gives them a quirky flare one might expect to encounter on courses in the British country side. The final result is a much more interesting set of holes and some good scenery along the way.

The con side is the soils are very heavy and the construction techniques of the original course further complicated its already poor drainage qualities in the rainy season. So despite the staff’s best efforts, it is fairly limited in the period it can play firm and fast. I saw recently Golf World ranked it as the 27th best course in Scotland — a nice feather in its cap. But I hope Mr. Kohler and the folks at the Old Course Hotel realize what they could have and go forward with letting Tim finish the rest of the course’s green complexes. If they do, it would make the Dukes an absolute mandatory stop on anyone’s multi-day St. Andrews trip and give it a shot at being on the list of the more memorable inland courses in Britain. Until then, it’s something of a perplexing 90/10 mix of phenomenal, old world charm accompanied with the a number of original greens giving it the lingering jive of mediocrity 90’s style.

Nonetheless, it has come a long way and Tim can’t be applauded enough. For a variety of reasons, I have a huge soft spot for it. It has come too far not to finish it off and find that spot among the list of best inland British courses.

What are the standout features from Coore & Crenshaw’s recent work on Pinehurst No.2?

Well, a great look at the big picture of the project was illuminated by Mr Padgett’s March Feature Interview on GolfClubAtlas.com. With the course now re-opened, people are once again getting a look at Ross’s wide corridored, ultra strategic course with every hole completely surrounded by a distracting potpourri of sandy hardpan, wire grass, scrubby pine. Bill and Ben put a tremendous amount of time and care into these precise grassing lines and how they would effect the strategy of the holes based off Ross’s versions. On some holes, depending on the hole location, the principle strategy of the hole is determined by these grassing lines.

They present you with opportunities to gamble as the odds of finding a decent lie in the native give you enough rope to hang yourself. That is where the genius of this concept shines brightest. The revegitation of these sandy hardpan areas was a major undertaking of this project and and it will continue to be an interesting experiment as the right balance of maintenance and restraint is found in the coming year.

A few greens underwent some slight adjustments to add hole locations that had been lost over time. The best of the bunch is the par 3 15th where the right hole location now dangles precariously over the right greenside bunker. The front right of the 17th green was modified as well creating a new hole location for the 2014 US Open.

The bunkers Ross built with his long time Construction Foreman and Director of Grounds, Frank Maples, were extraordinary and their integration into the native sandy landscape were like no other course seen before or since. With its sweeping flashed up sand faces, whiskers of wiregrass, and islands, they were quite unique in texture and style. In fact, Robert Hunter once described Maples’s meticulous work as arguably the best bunkering built during the Golden Age.

If that’s not a feather in his cap, I don’t know what is! This style was tremendously enjoyable with which to work. The goal of the bunkering was to tie in as seamlessly as possible into the surrounds and overall it required more intensive hand labor than any other project I’ve worked on. This created a fun and interesting process, as often times the primary tool creating shape wasn’t a machine but simply how a bunker was planted with wiregrass — or edged in short eyelashes to create texture.

The individual highlights of the restoration include:

-First and foremost the greens changes above.

-The restored concept on the tee shot on #7 which encourages players to cut the corner instead of automatically laying up.

-Renovations to all the bunkering throughout as well as new and restored bunkers.Some of the new bunking has a tremendous impact, such as on the par 5 16th where the right hand bunker in the approach has been restored to its huge scale as Ross intended. However the best bunker change may be behind the green of the same hole — where venturing into the last half of the green is now an intimidating proposition.

Over 75 years Pinehurst has enjoyed a rare feat in the design world — It has gotten better over its life span as a wrinkle or two has been added along the way to continue refining Ross’s masterpiece. With the character, intent and original charm now restored, it all comes together with those elements quite nicely.

I personally believe that if you are student of architecture, you’re education is not complete until you understand just how many sophisticated questions #2 asks on every hole location out there. To me St. Andrews, Royal Dornoch, and Pinehurst #2 are the three classic courses in the world, that allow for a depth of study that is beyond all others. It really is endlessly fascinating. With Director of Grounds, Mr. Bob Farren, Superintendent Kevin Robinson, and Assistants John Jeffries and Alan Owen now beginning to make the transition over time to a more ground game oriented surface, I think we can look forward to it becoming the best its ever been. I must say I can’t thank Bill and Ben, and the folks at Pinehurst for the opportunity to be a part of the restoration. It was quite possibly the most fulfilling experience in golf I’ll ever be a part of.

Considerably debate has ensued in recent years regarding the evolution of Pinehurst No.2’s famous crowned greens. The main theory was that accumulated topdressing had drastically raised the greens by over a foot to their height today making them more severe than intended. What are your thoughts on the evolution of the greens and what we see today?

This topic was an interesting side light of the project having had access to much of the old photography. Some have suggested Donald Ross wouldn’t recognize the green complexes today. I’m happy to say not only would he recognize them, when you are playing Pinehurst #2 today, you are in fact playing Donald Ross’s overall original concept. The greens are roughly the same basic elevations Ross built — and they have always been the same built up landforms we know today.

However, it is easy to see how the old photography led to this theory of the greens having ‘grown’ in height. I myself might have come to the same conclusion if it weren’t for the fact I had several months in the field working with the photography. It’s complicated! Pinehurst’s greens have most likely accrued some level of topdress build up, much like most old courses, up to 2-3 inches over time possibly, but nothing drastic. Maybe none, it’s hard to say for certain. That said, the theory that they’ve skyrocketed by over a foot to create the turtlebacked greens we see today by accident is in error. But don’t let me tell you…. judge for yourself.

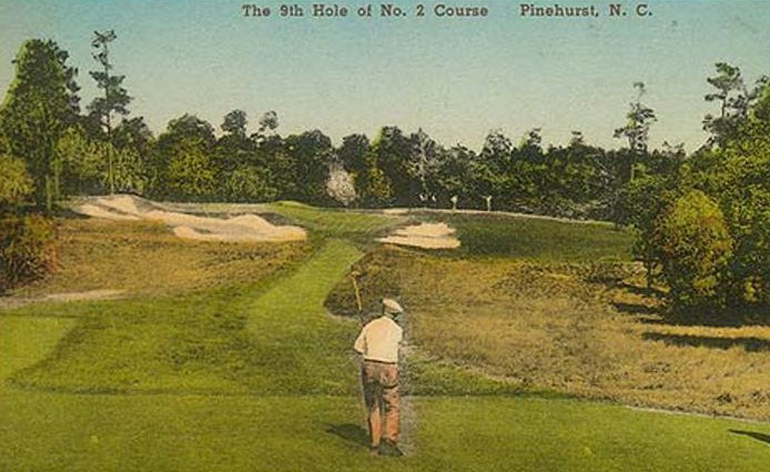

Compare the photos of 9th green from almost identical elevations with the bunkering now loosely restored and note the mowing line on the front of the green has shrunk slightly over the decades. Now here’s the critical point. With careful analysis in the field, of the entire green surrounds there is one feature that has never been been touched in 76 years that provides an indisputable measuring stick comparing the elevation of the 9th green then and now — the now abandoned back tee for the tenth hole with the golfers waiting on it in the photo from 1935. It is this base grade that shows us clear as day that Pinehurst’s greens are the same general elevation they always have been. Case closed. I could go around the course with comparison after comparison of bullet proof evidence such as this.

In the restoration world, the most simple answer generally wins out. And #2’s greens are no exception. The topdressing theory is built around the photography of a few holes. But armed with the full catalog of photography in the 1930’s and 40’s, one finds most of the rest of the greens do not look altogether higher and very different today at all. The reasons some of the greens look much higher in the old photography — and others not — is relatively easily explained. But first it’s worth noting that in analyzing the old photography, Pinehurst’s marketing department and their longtime photographer John Hemmer had a habit of shooting most of these 1930’s/40’s golf hole photography slightly elevated, presumable from a ladder. Golfers in the foreground almost always appear clearly lower. Because of this, many of these old shots slightly skew the perspective of the greens complexes when comparing them from ground level today. For example this effect is even stronger if the green slopes from back to front as it does on #7. Standing atop the high bunker on the corner of the dogleg on #7 one begins to see the perspective familiar to Hemmer’s great photos of the hole from yesteryear. Knowing that, one can start to make a unfettered comparison between photography of both eras. Comparing old and new photography from different elevations is simply a waste of time and because of this many of the photo comparisons that have been used as smoking guns supporting the topdress theory are irrelevant. So that said, the main reasons some the greens look raised in the old photography are:

1. The mowing lines on the edges of the greens have changed drastically over the years from their sweeping curling shapes. In many places around the greens today the mowing lines have been rounded off and draped further down the slopes. Other greens have shrunk. These changes have a big impact on a few holes when comparing the 1930’s-40’s era photography to today’s. Where mowing lines are lower down slopes today they look much more domed in comparison to 70 years ago… It’s as simple as that. A great example is the front and right edge of the first green as the grassing line is further down the slopes today creating this effect. It all fits back together as it should look when one flags the grassing line as it originally was. Another great example is the commonly encountered elevated photo of #11 green in 1935. The mowing lines combined with the high camera angle make the front of the green appear to run downhill initially in the first several feet of the green. This makes the green look as though the contouring and elevation of the green are completely out of whack compared with modern times because the start of the green runs up hill today. And that’s where the trick is — the front mowing line has been altered dramatically — not the green itself. Look at the photo below with todays grassing line added. In the 1935 photo, the green wrapped all the way down into the subtle swale that fronts the green. Nowadays, the front part of the green no longer includes the swale — It begins on the upslope that is clearly visible 10 feet further into the green in the 1935 photo. This explains the discrepancy and the green shapes make sense once again.

The 11th green in 1935 with today’s grassing line added explaining the unusual look that has led people to the false conclusion that the greens have been raised. The elimination of the green in the front swale happened very early on as Ross edited his own work. It had already been changed in time for the meticulous diagrams created for the 1936 PGA Championship and is confirmed by the photography from the 1940’s. Other photography indicates many other holes went through this major mowing transformation as they grew in during 1934-36. (Photo courtesy of The Tuft Archives)

2. It is fairly well known today Ross’s bunkers originally were very flashy sand faced hazards. In the decades that followed all high flashes were lowered for maintenance reasons. Over time the bunkers were also gradually deepened and evolved into the familiar grass faced style we came to know in modern times.

The lowering of these features is the second primary reason why some of the greens became unusually high looking compared with the surrounds. The bunkers began to take on a more sunken look and the greens as a result naturally appear higher. Thus it’s merely a trick of perspective and in the timeline of photography it’s no surprise the greens began taking on this propped-up look overnight when Pinehurst began removing the highest sand faces in the 1940’s and 50’s.

Now all that said, #2’s greens have been re-grassed numerous times over the last 70+ years. So as to be expected of any old golf course, these regrassings have softened or smoothed some of the smaller and more abrupt details on a few greens. This is specially true with the shapes at the edge of greens connected to bunkers. This cumulative effect translates to changes of an inch or two on a few of the lowest and highest features in select places. Its merely the going rate for a course as old as #2. It appears Ross, Frank Maples, and Richard Tufts themselves may have edited or tinkered with a couple greens along the way as well. Does that mean anything is wrong with the greens today? No. Because the greens are already teetering on the edge of functionality with modern green speeds in most cases this softening is in the best interest of the greens. The outstanding front left pin on #7 would neither be flat enough contour wise, or wide enough grassing line wise if it were the same as 1935. Finding lost pin space is the hard part of working on #2. Losing it is easy! The work that was carried out this year by Bill and Ben seamlessly handled some of this lost pin space. 17 mentioned above is a primary example. All those factors combine to explain even the most vexing images of the original greens complexes such as #4 and #7 green. Its entirely possible these discrepancies were intentional, perhaps even instigated by Ross himself. However the vast majority of the greens haven’t changed in any overly noteworthy way at all. So despite all the spilled ink on this subject, it’s much ado about nothing.

I think it is important that people understand these true factors behind the evolution of the greens because Pinehurst greens are worth celebrating for what they are — Donald Ross’s shining moment. Towards the end of his career in 1935 with decades of experience, having seen other courses of the golden age, and armed with the soils, budget, and a timetable Frank Maples and he could personally see to on an everyday basis, he managed to out do himself. I personally believe #2’s greens are still on the short list of greatest artistic achievements in golf architecture history and it was a pleasure getting to know them inside and out the last 9 months. As with any old course, a detail or two has been smoothed out, mowing lines and modern green speeds may have changed, but Pinehurst’s greens are still very much Donald Ross’s masterwork to be enjoyed today as they were then. What we see and play today is largely conceptually accurate to his vision.

Speaking of the ninth hole at No.2, Pinehurst Vice President of Marketing Tom Pashley recently discussed with me the interesting photography and process behind its bunker restoration. Explain this process and how these photos inspired the finished result.

The ninth holes large front left bunker complex was one of the last projects on the restoration. The front left bunker complex had been changed into two bunkers in the last 30 years and Bill and Ben took several months deciding whether it would be practical to restore it because of the maintenance issues that likely led to the separation to begin with. That’s a good lesson right there. Bunker work and restoration are equally maintenance driven as they are art. Once Bill became comfortable it was feasible I was sent in to build it. There are three different excellent photos of the hole including the one above, another from the 1936 North and South Tournament, and one from the 40’s with a slightly more grassed faced look to the bunkers. It is interesting in how quickly it evolved. It made the most sense to use a blend of all three but particularly the 1936 North and South image. It was the best looking, easiest to rebuild, and would require the least amount of maintenance headaches. And I knew that would make Bill and Ben happy! That’s how she tuned out… A nice place to end the project — the hole that had arguably always been my favorite on the course.

You also worked down the road from Cal Club at Pasatiempo Golf Club when Doak’s Renaissance Design was restoring the bunkers. What impressed you about this MacKenzie design? The black and white photographs from the mid 1930s are so spectacular, especially as homes hadn’t encroached into the field of vision then.

The back nine with its quartet of barrancas is one of my favorite sets of MacKenzie holes anywhere. It’s an absolute must see for the routing alone. And the greens are an awfully impressive set in their own right. There may be no architect who ever surpasses MacKenzie at building great par fours in the 380 to 410 yard range and 11 and 16 obviously fit the mold. When you stop to think MacKenzie considered #16 his favorite hole in his career its hard to not recommend Pasatiempo on that fact alone. And of course in the historical context it sat right at the tail end of MacKenzies red hot period from 1926 to 1929 and is one of his most personally involved projects. So it’s a great study of this portion of his career with its penchant for long gull winged/kicker green complexes and some of his most sophisticated bunkering. And while the native grasses and chaparral oaks that gave it that uniquely Northern California feel are gone, it still has a very old fashioned atmosphere with the little gate house entrance and finish at the base of the Hollins House. And on a personal note I must say given the fact I grew up playing public golf its great that a course so steeped in history, with such architectural significant history, is available for everyone to see and take a crack at one of the Good Doctor’s best.

You worked as the Lead Shaper and a Design Associate and at The Prairie Club in Valentine, Nebraska for Tom Lehman and Chris Brands. The course was voted the #2 best new course in 2010 by GOLF Magazine yet comparisons are always going to be made to Sand Hills and Ballyneal, two of the best courses built since World War II. Does the Prairie Club hold its head high in such august company? If so, what design attributes allow it to do so?

I’m a pretty good person to give an honest assessment for a number of reasons. For starters my name isn’t on the design but I obviously know its intent inside and out. My resume was doing just fine before I worked on it and I’m not personally invested in the Prairie Club Development other than I’m proud of the results and excited for their chances of success despite the tough economic times. I have no immediate plans to work for Tom and Chris in the future. So I can say whatever I feel like about it free of retribution!! Kidding aside, Sand Hills and Ballyneal happen to be two of my favorite courses anywhere and I’m quite happy to say it absolutely is in that same august company. Of all the new courses I’ve been associated with four stand above — Pacific Dunes, Barnbougle Dunes, Bandon Trails, and The Prairie Club (Dunes Course)! And it is without a doubt more than deserving of a spot in that company and is certainly one of the best I’ve been around. But don’t let my puny rationalizations or the Golf Magazine rankings be the deciding factor whether you go see it. Go see it because it is part of the Sand Hills family and it truly is in the group of the very best golf courses built the last decade. It has its own unique style that any true student of architecture can revel in getting to know for days and absolutely no one should miss it.

As for the design attributes that put it in that company, a couple of overall themes make it one of the more unique concepts built in recent years. The first and foremost reason is that with a total of 100 acres of fairway turf its right up there as the widest course ever. It has very large, interesting greens — obviously intended to provide as much ground game interest as possible. In many ways it is a similar overall conceptual idea to Old MacDonald. So obviously it isn’t lacking the basic building blocks for strategic variety day to day. But where it starts to take on its own personality and work really well is the fact with all that width, it is peppered with more central hazards than any other course I’ve seen. That simple dichotomy of 100 acres of turf versus the world record for well placed central hazards works incredibly well. One’s first inclination is it has a few too many bunkers, but at 100 acres of fairway it works surprisingly well for all levels of players. Even better than I expected once I started playing it and getting a feel for it through grow in. A second point that can’t be overstated is that Tom and Chris arranged the routing to attack the landscape just how one should — in as many ways as possible. The topography is a mix between Sand Hills and Rye Golf Club in England — but instead of two linear ridges to route off of like at Rye, there are dozens of them.

Tom Lehman’s two favorite courses are the Old Course and Shinnecock, and the former’s influence is immediately apparent in the green sites choices themselves. All that said Tom and Chris have to be given a lot of credit for a really outstanding routing in nearly prototypical Sand Hills land. As for the holes, they are uniformly excellent with #2, #3, #4, #5, #6, #7, #8, #10, #11, #12, #13, #15, #16 all legit potential candidates for the All-Colorado/Nebraska/Kansas Sand Hills Eclectic 18. There is a couple of holes there like the 4th, 6th, 16th, and 12th that I can guarantee you haven’t seen anything like them elsewhere! And as an overall set, the Dunes Course is right in with my favorite set of greens on any course I’ve worked on. A lot of effort was given to generating a concept that gave the course its own style rather than just go through the motions of making it a Sand Hills, Ballyneal, Wild Horse, and Prairie Dunes knock off. It is largely successful at that and adds its own take on what you can do out there.

Amid the positive reviews I’ve only heard two criticisms of the course. A few of people say the routing has too many uphill shots and the greens are too big. However neither criticism holds much water. The person who felt the greens were too big, dulling out the strategy, used the 2nd green as his prime example. Yet the 2nd green’s best pins are all at the margins and were designed to be attacked from only very specific points in the fairway. Explain why that green is getting any better and more strategic if its smaller? I’ve heard the same criticism of the Old Course by over served Americans in the Dunvegan Pub a hundred times! In addition there is all kinds of interesting decisions whether to approach in the air or on the ground. And I guarantee there is no one that thinks that green is too large with a big south wind going. And as for the number of uphill shots, after two years out there take my word for it, those are the 18 best holes on the property.

It’s been a fascinating study on this one having been on the opposite side of the ledger when it comes to the architectural hype machine. The vast majority of people who come see it open minded and just love it. And conversely there seems to be group of naysayers who want to dismiss it without having so much as even seen it or taken the time to learn the course simply because it is not designed by Tom Doak, Bill and Ben, or Gil Hanse. The irony is I think they are likely to be among its biggest fans — Gil Hanse already is one of its most vocal supporters. I think that’s as good of an indication of why it received such glowing press in Golf Magazine and Golf Digest, but was panned by Golfweek — who white washed their way through it as a group on one calm afternoon last summer. If you were to ask Tom or Chris this question they would probably say they are happy to let the golfers decide. But I’m quite happy to say it, if you don’t think its a candidate to be in the group of the best courses built in recent years, you either still have a lot to learn about architecture or you better get to know it better!

What are the critical elements going forward to showcase the design of the Dunes Course at the Prairie Club?

Obviously, getting it linksy fast for one. From what I hear of last summer Mr. Ross Buckendahl, Director of Agronomy and Co. was on their way to handling that with flying colors! Few golf courses I’ve worked on are as geared to play fun and interesting in fast conditions as the Prairie Club. So I’m sure he’s enjoying finding that correct balance. One area I think Ross will have fun these first few seasons is experimenting and utilizing all his tools for set up day to day. With the 100 acres of fairway turf, big greens, a large variety of tees, and winds that can blow equally hard from all directions, their is a lot of golf out there! And it can’t be overstated how critical setting it up to play fun is to maximizing the design for both the enjoyment of guests an the variety for the membership. The design certainly gives it ample opportunity in any condition to play fun and interesting. Finding the pins that are funnest in certain winds, the tees that play interesting in certain winds as well — it is a lot with which to tinker. And I think he and the boys will enjoy the challenge of utilizing all of those elements at their disposal to make it work well. There’s a reason they intentionally omit ratings and slope from the scorecard at Sand Hills as it is a moving target each and every day! The same principles apply at the Prairie Club. My description of the course above is 100% interdependent on Ross having the flexibility he needs to let it play the way it should. Great courses are only as good as their set up and he is just the right guy to do it.

Tell us about the bunkering at the Prairie Club.

The bunkering obviously was a tough task since Sand Hills and Ballyneal for my money are right next to Friars Head as the best bunkering I’ve seen. Will Smith and I spent a lot of time driving around trying to get a foot hold on what kinds of natural blowouts would be slightly different from the other two to emulate and give us the best look. And fortunately we were able to find some areas to give it an identity that aren’t represented by either Sand Hills or Ballyneal. Overall we tried to capture blowouts in all stages of development, from low scrapes that were just beginning to develop to the bigger formalized versions we see at Sand Hills and Ballyneal. In a lot of cases, this meant more native vegetation in bunkers and creating as much variety in their scale as possible. One interesting style we tried were cattle trail-esqe bunkers — narrow pathways that are created by cattle in the grasslands, presumably looking to jump a fence and run roughshod over passing cars like mine.

We also tried some hazards reminiscent of the early bunker evolution one might see in Hutchinson’s great old book British Golf Links with isolated sections of wood faced bunkers in otherwise raging Sand Hills blowouts. Not perfect wall to wall wood faced bunkers like The Cape Bunker at Westward Ho, or Royal West Norfolk — our versions were in short rows comprised of our on site fence posts. They were applied in places that would naturally erode and become a maintenance problems. I’d seen this in Hutchinson book, some other old photos I came across in Britain, and in Wales at an obscure little course called Porthmadog — and had been excited to give it a try since. Tom and Chris thought it would be something fun to try within the rest of the bunker concept since there was actually a couple existing wind brakes the ranchers had built like this themselves. So with that, these bunkers fit the site already to a degree. If your interested in the complete rundown of the goings on here’s a link to a video ( http://punchbowlgolf.com/2009/04/kyle-franz/) on the subject from punchbowlgolf.com.

One thing I know Tom and Chris would say if you asked them is how appreciative they were of our entire crew out there. Tom much like Ben Crenshaw, is a fun and incredibly down to earth guy. Chris Bands is as well. We had a great team and had a lot of fun. For myself it was a dream come true to work in the Sand Hills. The team included myself, Will Smith, George Waters, Phillipe Binette, and Jack Dredla shaping, as well as Ron Ferris doing the greens final preparation.

The Nebraskan Sand Hills goes far beyond prototypical golf land. While working there, what else did you experience?

I hit a loose bull on Highway 97 just outside The Prairie Club gates and it demolished my beloved 99 Dodge Durango. The Bull lived…. the car didn’t. Dazed, the bull merely sat in the grass, collected his thoughts, and took off looking for another hood ornament to dive in front of. As one can imagine I do a lot of white knuckled driving now that I’m in moose and bear country in Nova Scotia!

Kidding aside and being fair to the good folks of the Sand Hills, there is a lot to recommend the Prairie Club and Valentine just as a destination in addition to the golf merits. To go along with the scenery of the dunesland and Niobrara River Canyon, there is hunting and trophy fly fishing on the Snake River. There is also fishing of all kinds on one of the Midwest’s finest fishing destinations at Merritt Reservoir through the Merritt Trading Post Resort and the Bauer family. And a golf trip to the Sand Hills is not complete without a stop at Merritt Resort and The Water’s Edge Restaurant — where the drink specials are served up by one Stacy Ann Bauer, who not only is something of a cross between Annie Oakley and Meg Ryan circa 1990, but is about as entertaining as a barrel of Yosemite Sams.

You have been at Cabot Links for sixty days now helping to get the course ready for its ten hole opening in July. What can visitors expect later this summer?

First off, it is worth mentioning how great it is to be a part of a project that will no doubt make such a positive impact on both the local community as well as the environment in this sleepy corner of Cape Breton. The Canadian and Nova Scotian golf communities should be excited and proud of both these aspects in addition to the high quality of the golf.

As for this summer, golfers can expect to see what may very well become the best golf course in Canada on probably the best site anyone has been handed in the nation’s history. The coastline at Inverness is incredibly beautiful and it is a remarkably fortunate that a project like it was feasible for development in this day and age, especially given its proximity to the coastal route up to the national park at Cape Breton Highlands. Much like the preview loops at Pacific Dunes and Bandon Trails, golfers can look forward to a couple of holes likely to land on Josh Smith’s painting list. And they will see some of the meat of the order so to speak as well in this ten hole loop. As to be expected, a little time is still required to get that laser like links golf turf speed but golfers will be able to enjoy their first taste of true links style golf in Canada. It is hard to argue with that!

This is the first time that you have seen the handiwork of Rod Whitman. What are your thoughts?

Bill Coore once described Rod as the one of the most talented people in the business — and no one knows it. That is going to change! Rod’s work is so highly thought of by friends and associates I trust, and the photos of his original projects looked so intriguing, he’s long been on the short list of architects I would have liked to have met. Unfortunately, I’d never been within a hundred miles of his work. But if Cabot is any indication of Rod’s work to date, then I’ve been seriously missing out for a while. He’s built a really great golf course and sneakily one of my favorite routing plans I’ve seen. And a lot of how he approaches strategy and restraint is very similar to what I love on the old links as well. So I really can’t wait to get out and play it myself. His attention to details and his work habits are most impressive given the fact he shapes and builds his own courses himself. I think that’s a good lesson for anyone who wants go into this business. It’s great to see someone like Rod who has done such great work and put in his dues get a chance on amazing coastal land commensurate with his talents.

Your time living and working in the United Kingdom allowed you to see and study several hundred (!) courses. Which ten are must see links for a student of architecture? What about five hidden gems?1. The Old Course – I’ve walked the Old Course 100 times and I’ll probably walk it again 100 times more before I die. I’ll probably learn something new each of those 100 times. It simply can’t be studied too much.

2. Royal Dornoch – My personal favorite course in the Isles.

3. Muirfield

4. Ballybunnion

5. Royal Portrush

6. Royal County Down

7. North Berwick West Links – The greatest example of how simple, natural, zainy, and entertaining golf should be.

8. Rye – Probably the most underrated course in Britain.

9. Turnberry – It has become popular with some architecture aficionados to discredit Turnberry. Don’t buy it, it’s really good!

10.Lahinch

Under appreciated or hidden gem links next in line worth studying:

1. Prestwick

2. Royal West Norfolk

3. Royal St. Georges — Under appreciated is the wrong word for Sandwich, but it’s certainly my third favorite of the Open Courses.

4. Cruden Bay

5. Saunton (East Course)- This selection might surprise some but I’ve always felt Saunton is conceptually somewhat under appreciated. I’ve always been a big fan of the numerous holes in the British Isles where the hole’s strategy is simply to play to the correct side of the fairway to allow a perfect angle and view for the next shot — while playing to the wrong side of the fairway leads to a partially blind next shot to part or all of the green. That’s great, simple architecture. There are countless great individual holes of this ilk in the British Isles, but when it comes to this style being used as an integral part of the courses concept, Saunton takes the cake. With only 54 bunkers and its penchant for the aforementioned style of golf its amazing how well this course works. Their is better courses in Britain but for the serious student of architecture I’d give it the nod over a number of more heralded, heavily bunkered, and arresting courses that aren’t as an effective study for everyday play. And it doesn’t get enough credit for its greens and some excellent individual holes. On top that it gives one an excuse to go Westward Ho! and St Enodoc in the southwest. Which means I haven’t led you astray from the next course I’d list.

Which five courses were perhaps either too obscure or have made the most impressive improvements since Tom Doak published his Confidential Guide?

1. Brora – Now that its found a perennial home in the UK course rankings, Brora is far from being unknown today. However, considering how good the holes are I’d still say it’s one of the most underrated courses in the British Isles. It should be on everyone’s Dornoch trip itinerary.

2. Panmure – Overshadowed by its famous neighbor up the railway at Carnoustie, it’s easily overlooked because of it’s quiet ground around the clubhouse. But trust me there is nothing quiet about the stretch of holes between 4-13! It’s a mandatory trip to see the 6th, 8th, 9th, 11th, and 13th alone — the latter is one of my favorite bunkerless holes I’ve ever seen.

3. Portsalon – It has gotten some well deserved notoriety in recent years. Like Tenby, it has become a legit course compared to a couple decades ago. And it is worth the trip alone to see the second hole, a candidate for the best hole anywhere no one has heard of.

4.Tenby Golf Club – Famous for its sandy blowouts image in the The Anatomy of a Golf Course, Tenby was apparently “an almost unmaintained links” as Tom found it 25 years ago. Somewhere along the way they decided to take this neat little course a little more seriously! Not every hole is a wonder as it crosses the railway into some less sandy ground for a couple holes. But nevertheless it is well worth adding to a southern Wales trip.

5. Tarbat Golf Club – Portmahomack, Scotland – There is certainly plenty of courses countrywide that might be more worthy. However I can’t help but plug this largely unknown little 10 hole course as I can whole heartedly recommend it given its proximity to Dornoch (make sure you play the alternate “16th” to make it an even ten holes). There is plenty of design merit besides location. It was laid out by none other than John Sutherland in 1909 — And if you know your Royal Dornoch history you know it’s pretty safe to say he was riding a nice little hot streak from 1890-1910 from the creativity standpoint! If you’re in town to see its famous neighbor and have a little spare time in between rounds on the big courses make the 20 minute trip over for quick warm up or late evening evening game at Tarbat. There’s a few excellent little holes any keen student of architecture can enjoy and it is a prime reminder of how simple the game can be while still being architecturally relevant.

Which ten holes in the British Isles do you wish you could say you designed that aren’t well known?

I can’t possibly narrow the list any further….

#7 Pennard

#3 Royal County Down

#12 Swinley Forest

#7 Fraserburgh

#9 Royal West Norfolk

#12 Tenby

#13 St Andrews Old

#13 Panmure

#15 Muirfield

#17 Brora

#13 Royal County Down

#1 Tarbat

#6 Western Gailes

#10 Turnberry

#7 Royal Porthcawl

#6 West Sussex

West Sussex – #6

#8 Saunton (East) – A great simple hole where one checks the hole location walking to the adjacent from the 4th green to the 5th green to set up the line on the tee shot for the and angle for the approach for the day.

#4 Woking

#14 Rye

#15 Swinley Forest

#3 Royal West Norfolk

#6 Lahinch

#4 Rye

#16 Saunton

#5 Isle of Purbeck

#8 Royal West Norfolk

#16 Cruden Bay — The interaction of the back left and front right hollow, and back right bank — the only place one can land on the green with a backstop on windy is some great simple trick.

#9 Saunton

#13 Prestwick

#4 Saunton

#15 Royal St. David’s

#4 Royal St. Georges

#4 St Enodoc

#4 St. Georges Hill

#7 Rye

#2 Portsalon

#2 North Berwick

#4 Westward Ho!

#3 St. Enodoc

#9 North Berwick

Honourable Mention- First and second holes on the original Old Course abandoned, alternate routing — 1st tee to Road Green and Road Green to Corner of the Dyke Green.

What is the business outlook for your generation of architects? Not many new courses are slated to be built in North America over the next five years. What looms bigger for you personally – the restoration/renovation route or international opportunities?

As tough as these times have been, I believe the golf design and construction business will emerge a leaner, stronger, and more self sufficient one than it had become in the last decades. The interaction between overpriced contractors, architect, mass grading, irrigation budgets and mediocre cookie cutter results had clearly already pushed the business in an unhealthy direction. It was an economical cliff the business was destined to tip off the edge of and it could only dangle from a daisy for so long. Well it got tipped off the edge a little early. Now every dollar and every acre counts. It always has. As sophisticated as today’s market is the business will have to rethink itself to a degree. It can’t be overstated that the best golf of the last decade was the cheapest to build and maintain. Not to mention these places were built by architects who knew what they were doing from the design and budget standpoint, and were willing to do the work themselves. The high water marks are as diverse as Dave Axland and Dan Proctar’s remarkable achievements at Wild Horse on the most razor tight budget, to Pacific Dunes, and of course Sand Hills. That said I see the golf design business shifting down not just three avenues as cut and dried as Restoration/Renovation and International, but several avenues. Obviously the likes of courses on great land like Streamsong, Lost Farm, and Cabot Links will continue as will restoration and renovation. The darkest days of the great depression itself still produced a generation of world class projects from Augusta to Prairie Dunes to Highland Links even though very little else was built. There will always be a place at the table for courses that have a chance to stand the test of time with the right architectural and economic genetically make up to succeed. As for restoration and appropriate renovation, they are as good a reason as any to go into the business. Every old club should look into their past. One need only look through the photography to realize the success of Pinehurst was practically pre-ordained.

1. In addition every city in America should have a course as intelligent, fun to play, and economical as Rustic Canyon, Wild Horse, and Commonground. If the land and price is right, and they have the right factors to succeed they are still viable in The States. The more prospective developers learn to do their homework about their architect options and what makes those ventures work the more they are going to make effective business decisions and break the ice once again. It’s as old as golf in Britain and it should be the basis behind the future of golf in the United States. I’m not sure how this part of the puzzle gets missed.

2. It should become a cornerstone priority of this business in the coming decades to improve the existing golf courses we already have. I think everyone can agree there is an almost silent majority of existing courses and clubs today — Many of which are on quality property, modestly good routings, have perfectly capable existing infrastructure, that lack in the design department but have much a higher ceiling than they are achieving today. Many of these could stand to become better courses and tighten up there business and marketing practices with an appropriate scope of work at the bare minimum amount of design and construction output. Obviously in the process cater themselves to an entirely new clientele in addition to their current customer base. I’m not talking about a litany of soft costs, contracted construction costs, and every other dollar that gets swept into the witch’s brew. I’m talking about effective architect to client in house work across a timetable that is feasible. Architects who can and are willing do the work themselves on a timetable and budget convenient to their business model make these projects viable. And when I say doing the work I mean all of it. My old construction mate Kye Goalby was quick to point out in his Q and A the pitfalls of such ventures on a grand scale in the wrong situation. Indeed in many scenerios, MacKenzies analogy that “if it’s not getting better then it’s better left unspent” is accurate. That’s just capitalism in its purest form. But when it comes to the courses with a higher potential ceiling, if the price is right and it works, then it works. If it’s not in the cards it doesn’t. I grew up on a couple of courses that have learned the hard way what was really to be gained from that new multi-million dollar clubhouse or careless unnecessary course renovation that didn’t make sense.

More than that, I know what in a lot of cases hiring the local flavor of the week architect brings to the table — money that was better left unspent! And for those golf courses I worked on growing up, and those like them that threw money away by simply not having any idea where it ought to be going, there is an unfortunate and sad alternative which is to go out of business these days. For them, our expertise is a most valuable asset.

Of course, aspiring young architect want to build the next masterpiece on the shores of the Australian Coast or the dunes of the Nebraskan Sand Hills. So to some that may not sound sound so sexy. That’s fine by me, I’m equally as excited about the first example as I am the last. If I look back in 50 years time having spent 5-10 years slowly turning golf courses the likes of Pinehurst #1, Astoria Country Club, or fantastic little courses such as Fraserburgh or Golspie in the UK that could be world beaters into courses that maximize the land, I will have enjoyed a fulfilling career. I very much enjoyed looking into the history of the other courses in Pinehurst and was shocked to find what neat golf courses they all were. I certainly hope that pealing back the layers to showcase a very impressive Ross design at Course #1 is something that happens around the resort some day. If I did the same scope of work on obscure courses on good land and nice settings such as Gearhart Golf Links or Salem Golf Club in my home state and turned them into bullet proof hidden gems with good golf that everyday people can enjoy, I would have had an equally fulfilling career as well.

There is plenty to be said for good architecture and affordable golf that anyone and everyone can enjoy. You don’t have to build perfect courses and top one hundred candidates to build great golf that matters. The business is what it is these days. But for those who truly love architecture, the design process and the art of building it in the field, and are willing to roll up our cuffs and actually do the work, there may have never been a better time than right now.