Feature Interview with Kevin Cook

May, 2007

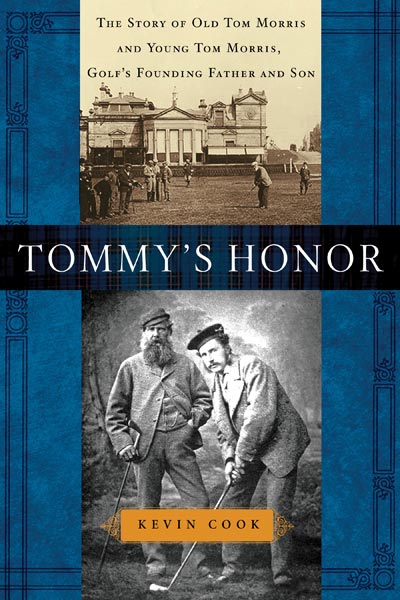

Kevin Cook is the former editor-in-chief of Golf Magazine. In his tenure there he helped grow the circulation to 1.4 million, and also wrote for the magazine and edited writers ranging from Jack Nicklaus to Gore Vidal. He has also written for Sports Illustrated, GQ, Playboy, Details, Vogue, Men’s Journal, and Golf Digest, and in 1998 won a Golf Writers’ Association of America Feature-Writing Award. He has also served as a senior editor at Sports Illustrated and an executive editor at Travel & Leisure Golf. He sometimes appears as a golf analyst on television and radio. He lives in New York.

1. You make the point that Ëœgolf evolved as a rich man’s game partly because the feathery balls of the 1700s and early 1800s, leather pouches packed with goose feathers, were expensive.’ In today’s dollars, how much did a feathery ball cost around 1800?

It’s hard to make a clean comparison, since the 19th century economy was so different from ours. Horses, wagons and labor were cheap, but clean drinking water was precious. By most estimates a pound then was worth £30 to £50 now, so a feather ball costing 2 shillings and sixpence would cost around £5 today, or about $10. The gutta-percha ball that came later would cost less than half as much.

Featheries were valuable enough that ballmaker Douglas Gourlay put one of his top-of-the-line balls in the collection plate one Sunday. Here are some comparisons: A feather ball at 2 shillings and sixpence (2 ½ shillings) cost slightly less than a bottle of port at 3 shillings. You could buy a new wool shirt in St. Andrews for 6 shillings. The ironmonger Alexander Mackenzie, who doubled as an exterminator on South Street, sold packets of his Royal Infallible Vermin Powder for sixpence.

2. Old Tom Morris was not from a well off family. How was he introduced to the game of golf?

Like a lot of boys in St. Andrews he grew up knocking stones and corks up and down the streets, “with any kind of club we could get a hold of,” he said, “very funny things some of them were, too.” One popular game was sillybodkins, a kind of street golf in which a cork was used instead of a ball. Claret- and champagne-bottle corks were plentiful; you’d pound a few tacks into a claret cork and it flew pretty well. Boys would knock corks up and down the streets, aiming for lampposts or sleeping dogs.

Tom expected to be a hand-loom weaver, like his father, but got himself apprenticed to Allan Robertson, the town’s premier maker of featheries. Allan was looking for a talented partner to play foursomes matches with him. He introduced Tom to the finer points of the game.

3. How many clubs would Old Tom carry in the 1840s? What clubs would his Ëœset’ consist of?

You could carry as many clubs as you wanted, but most golfers used a smallish set of hickories that traditionally fell into three groups: drivers or “play clubs,” spoons for lofted shots, and putters. There were iron clubs called cleeks, too, but they tore up feather balls and didn’t proliferate until later. Depending on the year or even the day, Tom would carry a driver; a grass driver (fairway wood); long, middle and short spoons; wooden niblick; a rut iron or iron niblick; and a wooden putter.

4. When introduced in the late 1840s, what benefits did gutta-percha ball offer over feathery balls?

Gutta balls were much cheaper than featheries, and more reliable. They didn’t go as far, but didn’t split at the seams or get so soggy in wet weather. They flew more predictably than the slightly oblong feather balls, though not as far, and gutties were easier to putt, since a good gutty was almost perfectly round.

5. Why did Allan Robertson and Old Tom have a falling-out?

Allan’s main work was making and selling featheries â€2,456 of them in 1844. Tom worked for him. Allan’s business was booming, and he recognized the threat gutta balls posed to his livelihood. “The filth,” he called them. This was one of the first disputes over golf technology. Allan paid boys to bring gutties to his kitchen, where he burned them.

One day Tom was playing with an important member of the R&A. Tom ran out of featheries, so the man lent him a gutty. When Allan saw Tom playing “the filth,” he went ballistic and fired him.

6. What tragic event made Old Tom want to leave St. Andrews and move to Prestwick in 1851?

Tom and his wife Nancy’s first child, called Wee Tom, died at age 4 in 1850. That probably added to Tom’s willingness to leave town and make a new start in Prestwick. But he loved his hometown and would have stayed if Allan hadn’t been the main man there. Fortunately for Tom he had a patron, the R&A man Col. James Ogilvie Fairlie, one of the founders of the Prestwick Club. Fairlie helped Tom land the job of greenkeeper at Prestwick.

7. At the time, golf was a very loose affair at Prestwick and it was up to Old Tom to design the course. How did he decide to forgo the 18 holes that St. Andrews had made commonplace and settle for 12 holes instead?

He didn’t have room for 18 because the land he had to work with was hemmed in by the beach, the Pow Burn, a railroad and a stone wall. The course he laid out made clever use of the land, but holes still crisscrossed each other and golfers occasionally putted out while balls whizzed by their heads.

8. Please describe the 1st hole that he designed at Prestwick.

It was long â€578 yards at a time when a big drive went 180. Basically a par 6. The hole was noteworthy enough that one reporter took the time to measure it at 578 yards, one foot and seven inches. It called for a drive over a marsh called Goosedubs Swamp, usually with the wind off the Firth of Clyde blowing hard from left to right. The green â€now the 16th green â€sat on a rise above the Cardinal Bunker. This is where Tommy made a miracle 3 on the first hole of the 1870 Open Championship.

9. Were there common characteristics of the green sites that he originally found at Prestwick?

Tom liked elevated greens that kept the golfer looking toward heaven. But Prestwick’s humps and hollows suggested a quirky layout, so he improvised. The Alps Hole green sat (and still sits) in a grassy hollow beyond the huge Sahara Bunker. The Wall Hole green had the burn to the right and a stone wall a couple steps behind. The Green Hollow green was in a natural slough with dunes and ridges all around, while the Burn Hole green sat between the Cardinal Bunker and the Cardinal’s Nob, with the burn behind the green. The Lunch House Hole called for a blind approach â€he liked those, too. I think it’s fair to say he made the most of the plot of land he had to work with.

10. Please describe how Willie Park and Old Tom Ëœspurred the growth in professional golf.’

They helped make the game a spectator sport. They were great rivals from way back, representing two early hubs of the game. Tom succeeded Allan Robertson as the hero of St. Andrews, while Willie was the champion of Musselburgh, on the south side of the Firth of Forth. Park was a tough character, a long driver who took out newspaper ads daring any golfer to play him. He took the train to St. Andrews one day, looking for a match with the great Robertson, who wasn’t about to take him on. Willie and Old Tom became lifelong rivals, dueling in money matches and the early Opens, which they divided pretty evenly until Tommy came along to beat them both.

Willie and Old Tom played one of the wildest matches in early golf history, a money match at Musselburgh, where Willie’s supporters hooted at Tom and kicked his ball into trouble. So Tom walked off the course and sat in a nearby pub. The referee ruled Tom the winner, but Willie claimed victory, too, and the fans nearly rioted.

Years later, when the old warhorses were going gray, Tom was the game’s famous “Grand Old Man” and Willie was out of money. Tom agreed to a match â€in effect the first senior-golf event â€to give Willie got one last big payday.

11. The first Open Championship was held in 1860 at Prestwick. How many people played in it? Was it stroke or match play? Were amateurs included or was it just for professionals? How many holes did they play? Please describe the last hole of what had become a two man match.

There were eight players, all pros. The ladies and gentlemen of Prestwick had worried that the scruffy professionals would embarrass themselves, and some of the golfers showed up so shabbily dressed that the club’s sponsor, the Earl of Eglinton, gave them checkered lumber jackets to wear while they played.

It was stroke play â€a format that assured the event wouldn’t take too long. They played 36 holes, three trips around Tom’s links, and it came down to Willie Park and Tom Morris. Willie holed a long putt at the last hole to win.

12. Old Tom would win the Open Championship the next year. Please describe the Open Championship belt that he won and put on his mantle at his house a few hundred yards from the Prestwick clubhouse.

The Belt was made of red Moroccan leather at a cost of £25. The Earl of Eglinton commissioned it, and it was so coveted that in the first four years of the Open Championship, the champion got no money. A year’s possession of the Belt, which made the winner “Champion Golfer of Scotland” until the next Open, was thought to be reward enough. Only in the Open’s fifth year, 1864, did the champion get any money (£6).

The Belt was smooth red leather, festooned with half a dozen silver plates showing crossed clubs and other golf emblems. The big plate on the front, showing golfers at play, was the work of a careless engraver: It showed a man swinging a headless club.

The Open champion traditionally posed for a photograph wearing the Belt. That was tricky for Tommy â€the Belt lacked notches that would have allowed him to tighten it around his narrow waist. That’s why he has his fist pressed to his waist in those photos â€he’s keeping the Belt from falling off.

13. Allan Robertson died in 1859. The way was clear for Old Tom to return to St. Andrews. With the turf at The Old Course in poor condition, The Royal & Ancient was keen for Old Tom to return as Custodier of the Links. Was it a foregone conclusion that Old Tom would accept their 1864 offer?

In a sense it was, because he wanted to go home to St. Andrews. So did Nancy, his wife. But he was already well known in England as the great golfer and greenkeeper from the north. He was in demand as a course designer, and he could probably have squeezed the R&A for more money. Instead he took their offer, went home and served well and faithfully for more than 40 years.

14. What was his first major undertaking to the course upon his return?

He made great improvements on the greens at St. Andrews, turning threadbare greens into lush surfaces he sanded and raked until they were the best anywhere. Tom also enlarged many of the greens, continuing the work Allan Robertson had started, creating double greens that sped the pace of play, creating the outward and inward loops we know today. But widening the fairways was just as important. Tom cut back the whins that had crowded the edges of the course for centuries, forcing golfers to follow a narrow path from tee to green. By widening the fairways, he made room for the more freewheeling, crowd-pleasing style of play that Tommy made famous.

15. We know where the 18th green at The Old Course is today. Where was it before Old Tom moved it there?

Closer to Granny Clark’s Wynd, the path that leads across the first and last fairways to the beach. The old patchy Home green was in a rutted hollow. Tom built a new green beyond the old one. His workers’ shovels hit bone â€a mass grave dug during one of the town’s cholera epidemics. That scared some of the workers, but Tom told them to keep working if they wanted to get paid. In 1887 the R&A golfer James Balfour wrote that the Home Hole green “has been quite changed by the formation of an artificial table-land, which forms a beautiful green.”

16. Please describe the purpose of a rut iron.

It was a lofted cleek designed to lift the ball out of cart- and wheelbarrow ruts. (Another specialized cleek was the “water niblick” made by Robert Forgan â€it had a hole in the face to help you slip it through water and lift your ball out of a burn.) Tommy was one of the first to use a rut iron from the fairway, to hit high approach shots that hopped and stopped.

17. Compare and contrast how Old Tom liked to attack a course vs. Young Tom.

Tom played an old-fashioned, conservative game suited to the small greens and narrow fairways of his youth. He hit straight, shortish drives and bump-and-run approaches, minimizing errors, counting on his opponents to make more mistakes than he did.

Tommy was bolder. Thanks to his father’s work on the fairways, he had more margin for error and could afford to swing all-out. Thanks to Tom’s work on the greens, Tommy could hit a putt and walk off the green while the putt was still rolling, telling his caddie, “Pick it out ‘o the hole, lad.” It was Tom’s greenkeeping that paved the way for Tommy’s dominance, which no golfer would match until Tiger came along.

18. Young Tom won four successive Open Championships in 1868, 1869, 1870 and 1872. Why wasn’t the Open Championship held in 1871?

When the Belt was offered as the Open winner’s prize in 1860, the Prestwick Club promised that it would belong forever to anyone who won it three years in a row. After Tommy’s victory in 1870 made the Belt his personal property, there was nothing to play for. The Prestwick Club, the R&A and other golfing societies bickered over the expense of buying a new trophy and hosting the Open, which they saw as less important than their club championships. Everyone figured Tommy would win the Open anyway, and so the fall of ’71 passed without an Open. It was only at the last minute that Prestwick, the R&A and the Honourable Company of Edinburgh Golfers agreed to stage another Open in 1872. They chipped in to pay for a new trophy, the Claret Jug.

19. Young Tom met Margaret Drinnen in 1872 and married on November 25th, 1874. Old Tom did not attend the wedding, in part due to Meg being a woman with, as you write, a Ëœpast.’ Briefly describe the series of events that occurred after September 4th, 1875 through Christmas day, 1875.

Tommy and Margaret were the happiest newlyweds in St. Andrews. (And the best looking.) By the fall of 1875 Margaret was nine months pregnant. Tommy had agreed to partner his father in a match at North Berwick, a showdown against Willie Park and his brother Mungo. The trip would take half a day. Tommy didn’t want to leave his wife, but he chose to honor his pledge to join his father in the match against the Parks.

The match was almost over when a telegram came from St. Andrews. A messenger handed it to Old Tom. Margaret’s labor had begun, the telegram said, and she was in trouble. Come home post-haste, the telegram said.

The rest is in the last chapters of Tommy’s Honor. I think it’s one of the most interesting and moving stories in sports history, and I hope GolfClubAtlas people will check it out.

The End