Feature Interview with Jim Urbina

June, 2002

Jim Urbina was born in Pueblo, Colorado andgraduated from the University of Northern Colorado with a degree in education. He worked on thirteen projects for Perry and Pete Dye from 1982-1991, first as a shaper and then progressing into design and on site supervision. He started with Tom Doak in 1992at Charlotte Golf Links and has since been involved with Doak’s Renaissance Golf Design at Quail Crossing, Beechtree, Apache Stronghold, Pacific Dunes and currently Red Raider Golf in Lubbock, Texas. In addition, Jim has consulted with Tom on clubsacross the U.S. including Garden City GC, Yeamans Hall, Valley Club of Montecito, Pasatiempo, San Francisco Golf Club, and White Bear Yacht Club. He has traveled extensively overseas playing and studying many of the links land golf courses.

1. How did you get into golf course architecture?

I like to kid people when they ask me that question. My usual response is, ‘I couldn’t get a real job and I’m still looking 20 years later’. The truth is that I’m very different from most of your ‘typical’ golf types in that I never liked, played or even understood golf when I was growing up. I grew up in the tough steel mill town of Pueblo, Colorado and my family never had the opportunity to learn the game of golf. My dad worked two jobs most of my early life and it didn’t allow much time for leisure. I guess in our typical American house in Pueblo it wasn’t typical to have a ‘Ward tells June he’s off to play golf’ type of deal. None of my friends wanted to play golf so I just didn’t know the game.

I graduated from college with a teaching degree but I didn’t really want to teach right away so I got a job fighting forest fires and for a while it was the coolest thing I could have thought of doing. But my lungs and the rest of my body had different ideas. I was dating my soon to be wife and her dad was involved in the irrigation business for golf courses and after quitting forest fire fighting he was more than just a little interested in my getting a job at something worthwhile. Val’s dad got me a shot at a job working on a golf construction site for some guy named Dye. I had no idea who Pete Dye was, but I was pretty sure I didn’t really want this job. I showed up in flip-flops and they hired me anyway.

I spent the first day digging a ditch and I quit, telling my supervisor that this was certainly not my calling and that my mom would be really disappointed in paying good money for a college education so that I could end up digging in the mud. While I was telling everyone why I was quitting, Mr. Dye was in the construction trailer and he thought that I had a lot of guts to say what I said. He asked me if I could run heavy equipment and I said no, but was willing to learn. He offered me a job as a shaper and I didn’t even know what a shaper was. I’m sure some jaws dropped in that construction trailer that day. That was 20 years ago.

2. You worked for both Pete and Perry Dye from 1982 through 1991. What was your favorite project and why?

-

- When I started working for Pete, it was at the TPC at Plum Creek in Castle Rock, Colorado. I did some time working for Perry when I was not working for Pete as well and officially I was really on Perry’s payroll. My last job with Pete was at the Karsten Golf Course at Arizona State University. I was the on site associate and I worked with the shapers and the scraper operators and got the dirt moved and the rough-in of holes done based on his field notes and Pete’s design ideas. I will say that creating golf features from scribbled notes and sketches and sometimes just listening to Pete talk was difficult at best. His notes to me were it as far as plans went and then I had to go try to get things done without really anything to show anyone.One time at Karsten/ASU, Pete had stopped on the 14th hole and got down on his hands and knees and began to make a little sculpture in the dirt. He made his model of the green and the bunkers and the whole time he was mumbling to slope the green this way and angle the green that way and make the bunkers like so. He was doing all of this pretty quickly and I was watching and trying to get a mental picture of what he wanted and he would look at me and the other guys standing around and ask us if we understood and of course we all nodded our heads even though I was just starting to get a small glimpse of his idea and was trying to sketch something in my notebook that made any sense at all. He asked again if we all understood and then all of the sudden he got up and with a swift kick and erased my only guide for this hole to exactly what it was in the beginning, a pile of dirt.

ASU was kind of my understanding spot that there was idea’s and theories of design and even though Pete could communicate as good as anyone, I also understood that my education had just begun. I still remember that job as a turning point for me from just working to being aware of golf design. I was also really into construction and I was a good enough shaper at this point that I could do just about anything I wanted to with equipment. So I really thought I knew something but I also knew more about ‘How’ rather than ‘Why’ and I felt ready to learn more.

3. What did you learn from working with Pete Dye?

I learned that telling a good story relating to golf was always a great way to open up a line of communication between yourself and the people you are working with at any given moment. Once Pete had your attention then he could begin to describe was he was thinking of and what he wanted you to do for him. I always admired Pete’s ability with people and the way that he was such a creative person with everything he did. I liked it when Pete, with his creative streak, and his wife Alice, with her dedication to average and forward tee players, would debate the merits of things like a tee location. It seemed comical, but it was certainly in both of their minds to make the game something special for people to play and that they wanted people to enjoy golf.

I also learned from Pete that designs of his were subject to change without notice and so you couldn’t get too proud of something you had taken a lot of pain to build for him. When I first started shaping for Pete, he would tell me exactly what he wanted me to do and he didn’t dance around it, he said it and you were supposed to do it. When he retuned in two hours or two days or whenever to change the work with something small or just starting all over, I learned to be ready for anything and to realize that a lot of times those changes were the things that made something really great. From that I’ve learned that sometimes you don’t know how a particular idea will look or play and so you have to build as far as your idea takes you and then you adjust and if the idea is a dud, you can’t hesitate to change the whole thing. Not once did I ever see Pete Dye with a set of plans in his possession, but he could tell you every detail about his work.

The best lesson from all of this as it applies to me now is that I just don’t understand why people are comfortable drawing plans in the office and then hand it over to someone else and say, ‘here…build my idea for this green or that bunker’.

4. Is there any accounting for all the first rate modern architects that once worked for Pete Dye (i.e. what makes him a good teacher)?

Well, I’m trained as a teacher and even though I didn’t do it for long, I sort of understand teaching. I don’t know for sure that Pete is such a good teacher. He did allow you to be creative and he knew when to pull you back from doing something stupid. He didn’t have a lot of rules for you to follow as far as artistic work. I know for a fact that his design strategy was based on a set of principles, but he was always looking for places to touch creatively. He knew what worked. Pete and his son Perry flew me around to look at other work that they had done so that I could understand what was tried and true for them.

I also think that by Pete allowing each person who worked for him to have some artistic input, he created a very profound effect. I don’t think it created instant design genius in all of us, but it did inspire us to ask questions of his work and our own. It was always good to ask, ‘Why did you do that?’ and see where those conversations would go. I think you would have to ask the guys who really spent a lot of time around Pete, like Lee Schmidt and Bobby Weed if this was their experience too. Maybe everyone didn’t have the steep learning curve that I had. Remember, I came to this entire thing not so much for the golf, so I had a lot to learn.

I’d think it was be a really interesting part of a Pete Dye book for someone to write a chapter on the lineage of how he started and how many he started as well. I am sure that some of the stories to be told would be really interesting.

5. How was working for Perry Dye?

-

- I owe a lot to Perry Dye. He talked me out of a teaching career. I decided to return to teaching for a brief period because it was all part of that voice in my head telling me to get a real job. Here I am teaching High School drafting and coaching sports and Perry would call me in the winter and ask me if I was tired of teaching yet. Perry allowed me to enter into a pretty tight circle that included some very good people and I didn’t really fit the mold. Perry was looking for really good golfers and I wasn’t. He wanted all kinds of things in his design guys and I wasn’t any of those things…or at least not many of them. But I was very good on the equipment and my time running crews in fires had me prepared to keep aware of the situation of construction sites. He allowed me to explore the golf business and I think he liked having me around because I wasn’t there to punch a ticket and tell the world that I worked for the Dye’s.I once asked Perry at a Christmas party early on in my time in the business what Links Golf meant. No sooner than the words had hit his ears, he had arranged for myself and my wife to visit Scotland. I got to see a bunch of stuff in Western Scotland like Prestwick, Royal Troon and Turnberry to name a few. This was before it was fashion in our business to make that trip. I felt very lucky. Perry’s personal favorite was Prestwick and I could see why, with the wild greens, the sleepers galore and the famous Himalayas. I returned from this trip all pumped up about all the cool stuff I had seen and I was ready to start building it all over the United States. Wrong. American golfers weren’t ready for blind shots and radical greens and pot bunkers, brown grass and unraked sand traps.

It was clear to all of us in the business at that time that American golfers were asking for green grass, target bunkers, step-cuts, detailed maps telling them where to play. I loved the fact that though all of this, Perry still understood that interesting golf didn’t have to start with rocks around the putting green that house the PA speakers for the starter to announce the next group of GPS carts on the tee. He also understood that clients ask for things and that you try to give them what they want.

6. In what ways did Perry’s approach differ from Pete’s?

-

- Perry did work much like his father. It might even be fair to say that Perry’s whole company approach was to emulate his father’s ideas and copy them. Not a bad thing, really. Perry wanted to do great things in the business. He wasn’t always just doing design. I don’t think this is wrong or right, but it certainly was his to do with as he pleased.There were some differences. Pete didn’t care if his guys played golf or not. He kept the game as part of his interactions with us and we all didn’t question him about golf. Perry wanted you to play golf. Perry desired a five handicap or better. Pete didn’t like people on his Payroll and seldom had any in contrast to Perry who carried more than one hundred people at times. Perry would send people to see all of Pete’s designs as well as his own, before they did any drawing or construction work for him.

I can say that Perry likes a challenge and back then he really liked the smaller site of 120 acres or less. He liked a lot of golf in a little area. Sometimes he was criticized for this thinking. Nobody looks down on Merion or any of the tight stuff (even The Old Course) if it is really good. Look at MacKenzie for example. I think of Pasatiempo as an example of tight design. Perry wanted to create a formula and a way to do the small sites and sometimes things worked and sometimes they were very difficult to make the American golfer understand or like.

Even though some days were hard, I’ll never forget working for Pete or Perry.

7. How did you meet Tom Doak?

-

- I remember this very well. I was finishing the shaping of the TPC at Plum Creek in Colorado and Tom was working for the Dye organization. I didn’t really get to spend much time with Tom, but I remember the construction manager and I failing really huge when we tried to stump Tom at baseball trivia. We finally broke out an almanac with all the stuff you could ever know about baseball and we were asking him questions and he knew every answer. So my intro to Tom Doak was that he was a guy who didn’t know too much about construction and knew way too much about baseball.The next summer I was back shaping after a winter teaching school and Tom was on the construction team for Riverdale Dunes, a Pete and Perry Dye design in Adams County near what is now the new Denver airport. Tom didn’t know how to run a bulldozer and I taught him. At the time I really didn’t know Tom’s background or anything about his study of golf architecture. But you hear things around construction sites and you learn stuff, even if it isn’t the whole story. I knew Tom wanted to be a golf course architect.

The Dye’s were allowing Tom some creative license at Riverdale Dunes and he was really interesting to watch. The course was built on this flat farm ground that was near some sand pits. The truth probably is that the ground is worth way more as a gravel pit than a golf course. Tom began to show me slides of all kinds of golf courses he had visited in his extensive travels and we would talk about the stuff we were doing at The Dunes and make some attempts to use some of the things Tom wanted to use in the shaping.

I still think that The Dunes offers some of the most creative work that has ever been done in the Denver area. In fact for all of the stuff that has been built in Denver in the last 17 years, it is certainly the most interesting golf you can play for $26. The course broke all kinds of rules for modern golf design, especially in Denver. I don’t think that a lot of Tom’s ideas would have made it into the dirt had he not been working under the Dye umbrella. The work there was the kind of thing that now days would have had the Owner or the Management Company and the Golf Pro and the Golf Course Superintendent all telling us we couldn’t do all the creative stuff we did.

It is unfortunate that now days too many times too many people who aren’t as well studied as Tom Doak was (and is) want input on the things they think are important. Too Easy. Too Hard. Can’t Mow. Cart Unfriendly. The truth is that the golfer decides, but a lot of the people who like to stand around and give design advice have narrow interests. I like to say that letting a good architect/designer (they really should be called artist) design. Of course that person has to have some ability and I may not have known much back then, but I knew Tom Doak had ability and that he was a hard worker.

8. How did you come to work for Tom Doak?

-

- The Dye organization was fun, but it was really large. Perry had over 100 people on the payroll and sometimes you didn’t know who was doing what. It was Perry’s style and that’s OK. Tom wanted to do some special things and he needed my ability in construction to get things done. I knew I could always go back to teaching so I wasn’t worried about making the choice and I guess it was just time to move forward from the Dye scene. I was at The Masters in Augusta and saw Tom and I asked him if he had anything I could do. He said yes and he asked me to go to Charlotte, North Carolina. Tom had already signed up to do his first golf course, which was Stonewall. He had committed all of his time to that project. Gil Hanse was with Tom and Gil’s job was to do the bunker work at Stonewall. Tom had the Charlotte Golf Links deal come up and he really didn’t have anyone to turn to, so he asked me to sign on.Tom and I walked the site and he handed me a grading plan and a file full of pictures and notes describing what he wanted each hole to play like. Tom would visit me when not at Stonewall. He would make changes and I’d get all I could done until his next visit. It was a very fast track schedule. We started work the first of June and finished seeding in the middle of October. That entire project is a story in itself.

What I remember best is that the first visit Tom made was a real eye opener. As we were walking, I asked about putting a target bunker on one hole to better direct the golfer. He immediately turned to me and said that I needed to forget all the stuff I had been taught before that day. Here I am, thinking I’m getting smart about all of this stuff and he tells me that there are no rules in golf design. I’ll never forget that day. Over the next few months we continued that discussion and I was learning about the merits of golf design and began to understand what made the good stuff great. I remember asking about things like ‘Par 72’, and ‘Design Balance’, ‘Multiple Tees:, and ‘Equal Sized Pin Areas on Greens’ and to every one of those things, Tom Doak said, ‘Forget it. Forget all those rules and just be creative’.

9. What impresses you most about Tom Doak’s approach to architecture?

I think to understand what would impress someone most about Tom’s design work, you need to understand Tom’s approach to the game and to the community of golfers. I mean, you don’t have his kind of interest if you are just interested in the little stuff or the little details. Tom has a dedication to Golf. He has an understanding of the people in the golf world. I didn’t know that world at all. He could show slides of his travels and talk for hours about the things he has seen and what kind of golf had been played there. But he could also talk about meeting interesting people. He talked about how much he learned about The Old Course from caddying there for all kinds of different golfers. He understood that there was a point that when golfers stopped having fun with the challenge that they would blame the course. He also knew that when felt challenged and given options, golfers would return to play something again and again to explore the secrets of the course.

The playability of the course is always on his mind. He never wants to be boring or the same. He spends so much of his time around green complexes. Not only just looking at how they play from landing areas or from the line of play, but from all kinds of different angles and areas around the greens. During the course of a site visit, while I may be checking some drainage or talking to a shaper or answering questions about construction, I always know where to find Tom when I return. He’s around the greens and bunkers visualizing shots. He wears a lot of dirt out walking around checking and double-checking that he has everyone’s game covered.

A lot of his ideas are in print here and other places, so I don’t think I’ll go into all the little things. But I will say that there are two areas that continue to show me that Tom is different for a good reason.

The first is that all of us associated with Renaissance Golf Design have been fortunate enough to travel with or without Tom and see alot of golf courses around the whole planet. He doesn’t want us to see this stuff so we can copy things or recreate features; he wants us to be inspired. Never in my life would I have thought I would get the chance to play courses in the UK and Ireland and Australia and even to see some of the incredible golf that is here in the US.

The second thing is that through his travels he met many amazing people. People like Walter Woods in St Andrews and Archie Baird in Gullane. Getting to know them and to play golf with them and to see how much of their lives are dedicated to golf, but that they don’t have huge egos to go along with their achievements. By all rights they should, but just as in the game, in life, they know that being humble is good. The understanding that it may not be where you are playing but simply that you have the opportunity to play is something that I’m always trying to remember.

I get a kick out of all the people who are trying to figure out what Tom Doak knows and what he’s all about. Most of them have never just taken the opportunity to get to know themselves and what they are all about first and to go see the world of golf. They want the secrets they think he is hiding about design but they don’t try to understand that his love for the game and for the people that play it make him work harder than anyone I’ve seen, doing fun stuff.

10. What have you been doing for Tom since those early years?

I’ve done everything possible to do in the design business. I’ve also done everything possible to do in the construction business. I try not to smirk when someone who’s been shaping for 2 years and has never seen anything outside of the state or states they have worked in tries to tell me that they can’t do something or have never done something the way we want it done.

In my role as a design associate for Tom, I’m not the guy in the Footjoys showing up for a ride around the course in a cart and a nice lunch. I’ve done it and I can do it, but it’s not my style. I’m not stuck in the office doing plans. I like being out there in the middle of the action. I like the people and the interesting challenges. I can do a drainage plan at the dinner table while I eat my dinner. I know when a client is paying too much for diesel fuel or when a piece of rental equipment isn’t right for the job or when a contractor isn’t doing what they should be to make our design work. So I’ve done all kinds of things. Whatever it takes because I can. If that means showing up for a day to run a dozer and make something right for Tom, I can do that. If it means spending 168 days on site on a project, I can do that. If it means figuring out how to get 80 locals to help us build a golf course when they’ve never even seen one, I can do that. Every day is just new and fun for me. When it’s not fun, I know it is over.

11. Explain your involvement with Pacific Dunes.

For us at Renaissance Design and certainly for Tom, Pacific Dunes was our shot at doing something on the level of The Sand Hills, a place I visit often and thanks to Dick Youngscap, have grown to dearly love. We may never have the opportunity to work with a site like that again. So I spent 168 days right there on site getting it right. It wouldn’t be fair not to mention that Brian Slawnik was there working with us most of the time as well as all the rest of Renaissance Golf Design.

I likened myself as a band director. Tom wrote the music and I got the band to play it. We built this course and we didn’t use a golf course contractor. Our labor force was mostly local kids just out of high school and it fell into my hands to teach and direct everyone involved as to how we wanted to design and build this course. With all due respect to the last 100 years of golf course architecture, all golf course designers must concede that without a team of good, interested and talented people, the designs of the best of the dreamers could never have been done. We had no one on the construction crew who had preconceived notions about what our work should be. The design wasn’t something we had to protect. It became something we grew into daily.

The success of this course is certainly due to many things. Some things are obvious, like the dramatic land and the great routing that Tom did. No question the location and the area will take your breath away even when the weather is bad.

Some things are a little less obvious, but certainly noticeable if you look. I can’t say enough good about Ken Nice, the golf course superintendent at Pacific Dunes. He was totally and is today truly dedicated to our design and to the principles of links golf that the site requires. Ken was with us all the time and he never gave the usual mumbo jumbo about not being able to mow something or not being able to get us the look we wanted. He simply said he would do everything he could to figure out a way. I have so much respect for Ken and from him, I’ve learned that growing grass is much harder than we all believe it is and growing grass our way on our design may seem like we are asking for less, but in fact we are asking for the superintendent to be as creative as we are. Ken Nice worked his butt off during construction. He gave the project every bit of his attention and the construction crew busted their butts as a result of his leadership. Ken has quite a challenge for the future. He’s an American growing turf for links golf and it is not always a surface that people who haven’t been exposed to understand. He’s going to get a ton of pressure to make things too green and to maintain or water when he should do nothing. I’m glad he’s there.

Everyone loves the bunkers at Pacific Dunes. Tony Russell was a local dairy farmer and small dirt contractor and his brother is Troy Russell, the first superintendent at Bandon Dunes and now the Resort’s agronomy director. Tony became our ace in the hole and he showed me a whole new way to do bunker work without even knowing that what he was doing was total cutting edge. Tony doesn’t golf. He didn’t want to debate the merits of bunker design with us. He did help us understand how to be more efficient moving dirt, even though I thought I was about as efficient as anyone at getting dirt moved. Of course Tony knows everyone in the area, so he was able to find us some good people for other heavy equipment operator jobs. We would have definitely been hurting without Tony Russell and not too many people would ever know that.

The soil, grasses and bunkers at PacDunes help make it a course apart.

Even less obvious to visitors at Pacific Dunes are the soils and the grasses there. Again, here we had some challenges and Tom and I sought the help of Dave Wilber, an independent agronomy consultant. Dave was pretty fresh off of working on Kingsbarns with Walter Woods and he had gotten himself quite an education of links golf agronomy during that process. We asked Dave to help us with soil and grassing stuff. He showed us how to do something that I know will stick with me for every job I do no matter what which is treating the soils that will be the home of. I used to tease Dave about being ‘the Bug Man’ because he was always talking about soil like it was filled with all kinds of bugs and that if we treated it right the bugs would be happy. That’s totally making it too simple but it was funny to me. Dave came up to Pacific Dunes and spent nearly 30 days with us during construction showing us how to care for the soils. Sometimes he drove me crazy telling me to move a few inches of good soil out of the way before we shaped something and then move the good soil back. It didn’t seem like it was worth the trouble, but in fact, the few spots where we didn’t go as careful as Dave wanted us to don’t do as well as the areas where we did the right thing. Sometimes this meant keeping equipment off key areas and so people had to drive longer distances. I’ll never forget Dave telling us that Fairways aren’t haul roads, they are Fairways. I was glad he was with us.

I feel like I’m leaving a ton of people out of this, a bunch of our young guys put so much effort into things. I could tell so many stories of good things happening because we were there and we cared. There were so many things that made the job work. I’d like to take credit for it all, but the truth is we just had the best team you could imagine working with us.

European beach grass was hand planted to give this front bunker on the 11th at PacDunes its fingers.

12. What specific features pleased you most with the finished product at Pacific Dunes?

- There were so many things I was happy about and it was hard not to be happy with the property we had to work with. Not everything was easy. We had some tough issues to work out. The agronomy alone was incredible. We ran into some areas that were not blessed with great soil and we had to figure out how to make things right. I think I could write a whole book on the everyday trials of building that course.There is one story that kind of sums up how I feel. While we were finishing up on the last 6 holes in the fall of the year (the other 12 holes were done in the winter and spring of 2000), the resort opened some of the more mature holes for limited golf. While walking in one night from the north side of the property, I happened upon a couple that were just finishing playing their second hole. We struck up a conversation and they asked when the rest of the course was going to be finished and I replied that it would be next summer. His girlfriend, who was not playing, told me that she didn’t even play golf, but that she had just enjoyed walking the course and admiring the beauty she saw. Our discussion centered on the vegetation and the wildlife and all of the variety of land she had seen. That to me was truly the satisfaction of working on Pacific Dunes. All the work we had to do to complete an 18 hole routing including clearing, shaping, irrigation, grassing and maintenance of a playing surface and she didn’t even notice one thing out of place or unnatural. She told me that it looked like it had always been there. I can’t think of a higher compliment.

13. Describe the work you have done at Yeamans Hall.

I’ve been helping superintendent Jim Yonce and his crew with restoration and remodeling of the greens and bunkers. We’ve also widened the fairway lines and expanded some teeing ground. The greens as Yeamans Hall had shrunk to half of their original size and instead of being big and square they were little and rounded. We began by doing very touchy dozer work and probably were averaging taking off more than 50 cubic yards of material per green that was pretty much topdressing sand built up from years of maintenance. I would shove it into a pile on the edge of the green and then the crew would haul it away. When that material was gone, we would begin to reshape each green based on the old maps and pictures that Jim had found.

Someone asked me what those greens looked like before we started and all I could think to show was taking a dinner plate which would represent the green and turning it upside down on a big square placemat which was how the old greens looked. 70 years of topdressing will do that. Tom commented about this under his review of Yeamans Hall in THE CONFIDENTIAL GUIDE.

We are still working with Jim and his crew and in fact on my last visit they decided to do the first green. This green seems really out of place and we can reconfigure it and get it right. Jim Yonce and his crew is a reminder to us all that work can be done in-house with some proper site supervision and help. We can save the club money and time and we get the job done right because we can get the last little details done. I prefer to do work this way and I can’t understand why clubs choose to do the work any other way.

Lastly, Jim Yonce proved to me (as has Dave Wilber and Ken Nice) that minimal irrigation is always something to go for. He does add a head now and again, but he doesn’t like to use them. Water managed this way gives firm and fast fairways and good greens and a rough that is not so thick that it is an automatic lost ball if you find yourself just a few feet off a fairway. Jim’s work on making this rough what it is both from a look and play standpoint is amazing and I wish we could clone that effort as much as possible.

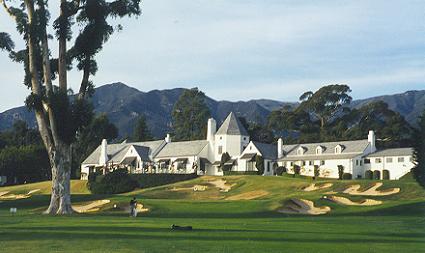

14. Describe the work that you have done at the Valley Club of Montecito and Pasatiempo GC.

The work being done at both places is mostly bunker work and is for sure restoration. We are done with the bunkers at The Valley Club and are progressing a bit slower at Pasatiempo. A lot of people like to say that this kind of work should be done all at once instead of two or three holes at a time. Doing it slower can be a bit more hassle for the club, but doing it on a slower pace has proven to me that artistic work like this can not be rushed. I firmly believe that if we had tried a quicker approach at either club the end results may not have been as exacting.

If you ever get a chance to visit The Valley Club, pay close attention to how Robert Hunter crafted those bunkers. They are truly amazing. The overlapping at opposing angles shows clearly that Hunter was taking the time to integrate the bunkers into the design and not just create eye candy. People are now saying how they want to do this kind of bunker work on modern designs but they don’t understand how painstaking it is to go from fun visual feature to incredible incorporated design features that are key to how the course plays. Our goal was to restore the bunkers that Robert Hunter had obviously taken great pain to create. I consider it a real privilege to have been able to do that. Everything was done from old photos and aerials and our archeological digging. You can’t rush this and much of it is handwork. Here again, doing the work ourselves has proven to be the best way to get it done right. The club is continuing with the master plan that Tom wrote. I’d really like to recognize Sean McCormick and his staff for all their hard work. Sean gave us the support we needed with his labor force and he got all the materials and supplies together. He was right there with us for every bit of the work, and when he and I had to discuss issues of drainage, etc. that would affect his ability to maintain the course, we did not hesitate to do the right thing.

Hunter’s distinctive bunkering at The Valley Club.

Pasatiempo is progressing with their work and we just completed the 10th hole, restoring baranca bunker and enlarging the green back to original shape and size. It was the biggest logistical challenge of the work we have done so far. Dean Gump, the Superintendent, again has shown me how capable superintendents and their crews can be when we help them learn what do to and how to do it. Our next work will be on holes #4 and #5 with more bunker restoration.

I always get a laugh when I read how certain designers have suddenly decided that they will do Mackenzie style bunkers. After doing restoration on so many of these bunkers I have to wonder exactly what that means. Do they understand that all of these bunkers have their own individual flavor? It could be a Hunter bunker or an Alex Russell bunker or perhaps a Fleming/Cole effort or possibly Perry Maxwell. It comes down to who actually did those bunkers. For instance you could possible argue that maybe the bunkers at Crystal Downs could have been Maxwell’s ideas. Look at the distinct resemblance to the bunkers at Prairie Dunes.

15. How is the work progressing at Texas Tech University?

The idea and challenge at Tech was to create something out of a dead flat piece of ground. Tom allowed all of us to route how we would envision the course taking shape and then once he settled on a routing, he asked us all to pick some of our favorite holes that we have enjoyed playing to influence grading map development. Our intention is never ever to duplicate a golf hole, but only to take characteristics that make some of our favorites exciting. No one can duplicate the great stuff and I don’t think they should try. For instance, duplicating Raynor’s ‘Short Hole’ and then building six sets of tees from 120-220 yards seems to be defeating the original design concepts. But Tom allowing all of us at Renaissance to talk about our influences and see where they might fit into the demands of the routing is good.

Once Tom decided what he liked, he and Don Placek did a 2-foot grading map of the job. Considering we are recognized as a design firm who practices the minimalist philosophy and isn’t known for working from plans, it turned out really good. TTU is not a minimalist design. It actually goes the other way. Over a million yards of dirt moved is quite a change far less than at Pacific Dunes.

It hasn’t been easy with as much going on with such a big job, but it is working. Eric Johnson is the superintendent and we had a lot of influence in that hiring decision and I think Eric is totally dedicated to our design. He’s got his hands full.

A lot of people think that this sort of thing isn’t something we can do and I think that they forget that we come from lineage in this business where moving lots of dirt and being creative about it was normal. I think once people see and play Texas Tech, they are going to think of Tom and Renaissance very differently.

16. You are extremely well traveled and have seen over 600 courses around the world. Talk about the travel aspect of being a golf course architect.

Tom told me one time when I was counting what I had seen and/or played that it wasn’t just the number but also the quality of what you have seen that counts more. I’m thinking now that I’d rather see one golf course of pre-1930 age than 30 more modern layouts. I’ve learned more by studying Ross greens and Mackenzie greens than anything fashioned in the early 60’s. Maxwell is my personal favorite. His greens are incredible to me and for me, it’s the greens that count as the areas where I think we really make a difference. Doesn’t it make sense to spend the most time and the most effort on the surfaces that you spend the most money to build and maintain? I rank the greens as the number one feature on any course and we give them this kind of priority.

I agree that bunkers play an important part of design, but in reality green side bunkers play supporting roles. Routing is also key. But for my money great greens can be The Great Equalizer. People keep talking about making things longer and harder because of length and I say put greens back to what they used to be with dramatic slope and movement and stop with the boring flat speed traps. Giving the player options as how to attack the hole seems a lot more interesting than making a bunch of long flat putts. I think a bad thing is done when we require that once a player (especially a Tour player) reaches the putting surface all they have to do is roadrunner the ball straight to the hole.

Anyway, back to travel. I travel. No doubt about that. It is a personal dedication. You have to make hard choices, like going to see something you haven’t seen instead of getting on the plane and heading home a day early. I run into shapers all the time that haven’t seen anything and I can’t find a way to make them understand what I’m thinking about. They just don’t know. It’s a problem for superintendents too. They don’t get to get away from their primary place much and it is hard to just tell them about something they haven’t seen. Pictures help, but I’d seen tons of pictures of the Old Course and none of them prepared me for what I got to experience when I actually saw the place.

Now more than ever, I meet people who want to do what I do. But they have no idea how hard it is. The challenges are hard and the work is hard and the travel might just kill you, so for me it means an extra bunch of desire to go see golf courses and to spend even more time traveling. But I always come away with something good or bad to put in the memory banks. But I’d say that there are very few people tough enough to do the kind of travel we do for Tom. Especially in my role on jobs like Pacific Dunes. I was there nearly 170 days and you have to account for the travel days to and from there. Plus doing other work. My family misses me and I miss them. I have to say that my wife is amazing for putting up with it and so are my kids.

17. Why do you think that there is such a new found fascination with golf course architecture?

When I was trying to learn as much as I could about architecture, there were probably only a handful of books available that average Joes like me could purchase on the subject. Today you can get online or walk into a bookstore and find tons of titles that focus more on the course than they do the swing or putting or whatever. There are multiple books on Ross and Mackenzie and on the stuff that has been lost and on the stuff that no one will ever get to see unless they fly to Australia.

GolfClubAtlas.com devotes most of its energy to architectural review and almost everyone who posts on the forums has answers to all of the questions. Sometimes reading it can be sensory overloading. But I think the web site gives your readers a wonderful medium to express their opinions on golf design. I think some of the topics are way too simplified given the real situations faced during construction, but very few people ever get to see and find an understanding of that kind of thing. And I think sometimes things are debated well beyond what is necessary to explain a certain idea or concept. It is hard for those of us working longs days to keep up with the volume and I have to confess that I don’t seek out golf discussions when I need some leisure time. I do peek at the aerial photos and that I find very interesting.

Sometimes I find topics interesting, but I also think to myself with all of the deep opinions flying around, I’d like to see some of the contributors try in the real world. Owners and Contractors and all kinds of people who know or think they know would have a very difficult time with the concept of tradition. More than once at Pacific Dunes for example, we were asked to think about the needs of the average golfer. You can’t just be idealistic when you have to deliver a good product and sign your name to it. It isn’t easy designing and it certainly isn’t easy building one on time and on budget. But, hey, I like the American way and that includes freedom of speech.

I often wonder when the moment was that today’s golf designers decided they could do as well as the next guy. When did Bill Coore finally think that it was time for him to do his own? What motivated Tom Doak to say that he was ready? I’m curious as to when someone who has primarily been a writer suddenly decides that it is time to design—says Ron Whitten for example. I think about that topic a lot and wonder who the next big contributor to golf design might be. Maybe someone who posts and believes in what they say on GolfClubAtlas.com will be taking their place as someone who influenced the history of the next 20 years of design.

18. What’s next for you?

Sometimes I’m having too much fun and am just too busy to think about it. I’ve gotten to do some great stuff and I’m sure that will continue. My stories are getting pretty good. I can talk about how to build a golf course with 80-90 Apache Indians like I did at Apache Stronghold. I can talk about building with a crew of young kids, cranberry farmers, loggers, fisherman and dairy farmers like we did at Pacific Dunes.

I just finished the restoration of greens and bunkers at the San Francisco Golf Club and I have to tell you that working on that A.W. Tillinghast ground was almost spiritual, but in the back of my mind I always had the idea that the best work I could do would be only to restore what he had already done. Tom did a great plan and we followed along and got that work done in just over 45 days and their new greens will hopefully be playable in October.

I’m looking forward to working hard to make sure we don’t rest on what we have done, but do good stuff in the future. I’m not just ‘the shaper’ or ‘the dozer guy’ now but I have those abilities and they serve us well because we build our own stuff and that probably won’t change. I like to be the bandleader and I know more and more about how much it is about the people you work with. I couldn’t ask for a better business to be in and I feel lucky every day.

I really enjoy working with Tom. People say we have a sort of shorthand between us and I think that is because we’ve done a lot of work together. I continue to learn from him and others every day and formulating my thoughts on design is always going to be an ongoing process.

I kidded someone that I would stay in the business until I found the Holy Grail. I think I’m on track and rounding the corner!

If I ever get a chance to do one solo (and I’m not saying I ever will), I may never (too scared), I’d like someone to write this about my work.

-

‘On more than half of the holes, a player has a choice of using his head or his clubs. In some cases he must use each as the hole opens up according to what you think you are capable of, visualize or actually do. By this there is more than one way to make par and still be doing so with a method of some degree of orthodox execution. Any hole that requires study and thought remains interesting indefinitely as they will on this course’

If I were to write a book or a bunch of essays or just cook up some food for thought, here is what I think I’d talk about:

-

-

Perfect Yardage

-

Base Camp Golf

-

A Bunker for All Players

-

The Great Equalizer

-

If They Built It Today

-

MacDonald’s: Fast Food Golf Course Architecture—Home of the Nuthin-Burger

-

Triangle Golf

-

The X Factor

-

Everyone’s Amen Corner (and other designs with a formula)

-

Shoe Horn Golf

-

The Lineage of Golf Design—Who Begat Who

-

It’s the People, Stupid.

-

What Comes First—Design or Practicability

-

Corridor Golf

-

What is Par?

-

The Holy Grail of Golf

-

Thank you to GCA for the honor of this interview. Thanks as well to my wife and family. And to Tom Doak and the rest of the Team at Renaissance Golf Design-Bruce, Don, Brian, Eric and Jenny. These words wouldn’t mean anything without them.

The End