Feature Interview No. 2

with

Jeff Mingay

February 2018

You worked with a hero of mine, Rod Whitman, for nearly a decade at places like Blackhawk, Sagebrush and Cabot Links. What have you been up to since going out on your own in 2009?

Mostly renovation and restorative-based work on existing courses. I was also fortunate to win the commission to rebuild the Derrick Club a few years ago. The Derrick is a successful, multi-faceted club in Edmonton, Alberta … social, fitness, swimming, racket sports, and golf. We started with a property that had an aged, troubled course and by the time we finished in 2015, the Derrick Club had a brand new course, completely re-routed, over 2,000 trees felled, an extensive new drainage system installed and every golf course feature rebuilt.

The course has been in play for three full seasons now. The feedback’s been very positive, even though it’s a bit of an unconventional layout in many ways. The club’s property has an odd shape, and is bordered by busy roads and residential homes on all sides. It seemed like every par 4 on the old course turned sharply right. That was one of its faults, along with poor drainage. When I re-routed the course, I was committed to simply finding the best holes possible. This resulted in a par 34–36 layout, where the “turn” comes after the 11th hole. The front nine has three par 3s at 2, 5 and 8. The back has one, at 16. There are only two par 5s on the course and they come at the 6th and 11th holes. Still, the course has an interesting pace. It starts rather subtly, with a short par 4 and a mid-length par 3, picks up through the middle, before finishing comparatively friendly. It’s fun to play.

The Derrick Club committee and Board was remarkably opened minded, which made a big difference. The end result is a course that’s really different than any other in the Edmonton area, and the province of Alberta. Other than Calgary Golf and Country Club, and Stanley Thompson’s work at Jasper and Banff, there aren’t a lot of classic courses in Alberta … or really anywhere in the Canadian west. So, to make the Derrick distinctive than everything else in the area, I drew a lot of inspiration from those classic courses back east like Essex, for example, across the river from Detroit, where I grew up playing.

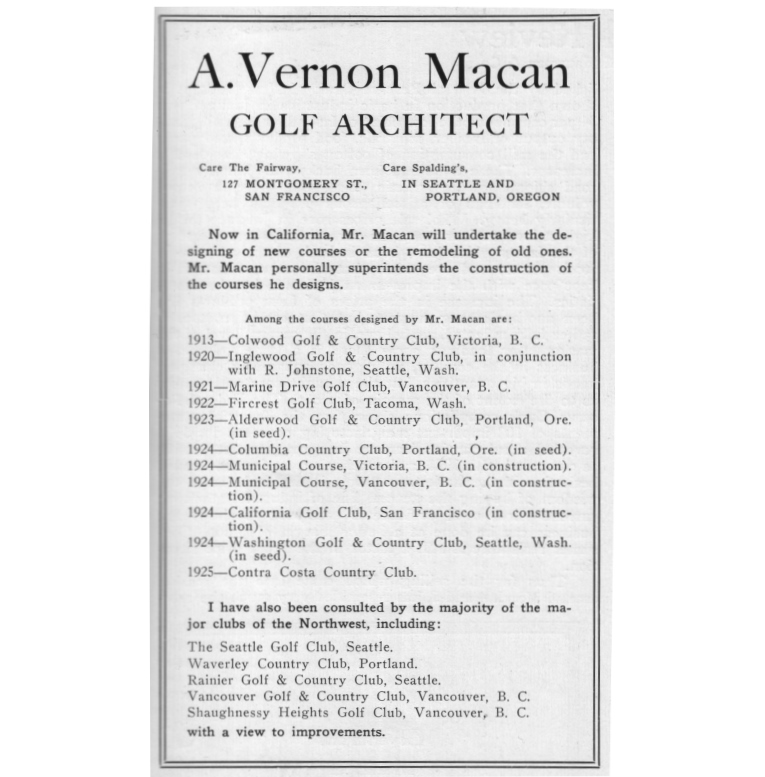

You’re currently working on seven (!) courses in the Northwest originally designed by Vernon Macan. How did that come about?

My first solo project was at the Victoria Golf Club, starting in 2009. In the summer that year, I was working with Rod Whitman at Cabot Links on the Atlantic Ocean and then, that fall, I started work at Victoria, on the Pacific. That was a neat transition.

The Victoria Golf Club was Macan’s home base for most of his life after immigrating to British Columbia from Ireland. Not only did he play golf there, he constantly socialized at the club and even ran his business out of the club. Macan’s letterhead featured the club’s address throughout most of his career. So, in researching for the Victoria project, I quickly learned a lot about Macan. Part of that research involved visiting other Macan—designed courses, mostly in and around the Seattle area, to start … Broadmoor, Overlake, Inglewood and Fircrest.

Inglewood was Macan’s second 18-hole design after Royal Colwood, in Victoria, which opened for play in 1913. He laid out Inglewood in 1919. Inglewood has a treasure trove of historic materials, including some excellent historic photos of the course in its early days. We’re in the midst of putting a lot of that work back together right now, in phases.

Anyway, I got to know people at the aforementioned clubs in and around Seattle. As our work progressed at Victoria, quite a few golfers from Seattle saw it during Pacific Northwest Golf Association events hosted by Victoria. That led to phone calls from the Seattle clubs. Scott Stambaugh was the first person to bring me down to Seattle, when he was superintendent at Overlake. Things snowballed from there.

We’re now working at Overlake, Broadmoor, Fircrest, Inglewood and Manito Golf and Country Club in Spokane, which is Macan’s third 18-hole design. I say “we”, because I’m working with a great contractor in Washington state, Kip Kalbrener and his RidgeTop Golf team.

We’re still working at Kelowna, too, in British Columbia, which is another Macan.

Retrace your steps. How did you become fascinated by Macan?

Travelling around to look at courses, I’d make lists of courses I thought I needed to see. During the late 1990s, I was in Vancouver, British Columbia. I knew I needed to see Stanley Thompson’s Capilano, of course. Then I started to list the other best courses in and around the city. Shaughnessy, Marine Drive, Richmond … they were all designed by this guy called Vernon Macan. I thought I knew about all of the legendary architects but I hadn’t heard of this Macan guy. The first of his courses I saw was Richmond. It was built in the mid-1950s, later in his career, on a shoestring budget, on an old farm field. With not much money at his disposal, Macan focused on the greens. The greens at Richmond are some of the most creative you’ll see anywhere. That is when I started to get ‘hooked.’

On the same trip, I was introduced to Mike Riste, Macan’s biographer. Mike’s a passionate historian, with a special interest in Vernon Macan. He was kind enough to have lunch and fill me in on Macan’s history, a lot about his life and a little about his architecture. Macan led a fascinating life that sparked my interest to do more research on my own, more specific to his golf architecture.

Have you seen the California Golf Club of San Francisco? Thoughts?

I have. Funny, the last time I was there, about 2009, I played with George Waters, Tom Doak and Jim Urbina. California Golf Club is one of my favourite courses. It’s one of my favourite places, actually. Kyle Phillips and his team did an incredible job renovating the course, turning it from one people had kinda forgotten about into a course everyone’s still talking about since the renovation. George, who’s also worked for me quite a bit, did a lot of the shaping.

Willie Locke was the original architect at the Cal Club. Apparently, club directors weren’t happy with Locke’s design and early progress, so Macan was hired to take over as designer after construction of the course had started, in 1923 or ’24. Shortly after Macan finished the course, Alister Mackenzie and Robert Hunter were hired to re-bunker the course. Then Kyle and his team made some significant changes to the routing, bunkers and some of the greens, too. I can’t confidently say how much Macan is out there at Cal Club any longer.

The Cal Club is a wonderful mix of a Locke routing, a Macan course, bunkered and renovated by MacKenzie and remimagined by Kyle Philips.

Reminds me of a great line from Bruce Lietzke. During the 2002 Canadian Senior Open, someone asked Lietzke how he’d compare Essex Golf and Country Club to other Donald Ross courses he’d played. Lietzke answered, “I don’t care if it was designed by Donald Ross or Donald Duck, I just like the course a lot.” I feel the same about Cal Club.

The last green I have putted off of (!) is the 13th green at the Cal Club and though uphill, it represents one of my favorite approach shots in golf. Name three other Macan greens that both inspire and infuriate.

Definitely the 9th at Victoria, which is another lay-of-the-land green at the end of a 200-yard uphill par 3 out on “the point”. It’s a beautiful hole, mostly because of how the green fits the landscape so perfectly. But that green has a wicked back-to-front, left-to-right slope that’s further complicated most days by a brisk seaside wind. Putting off the front-right corner of this green is easy to do.

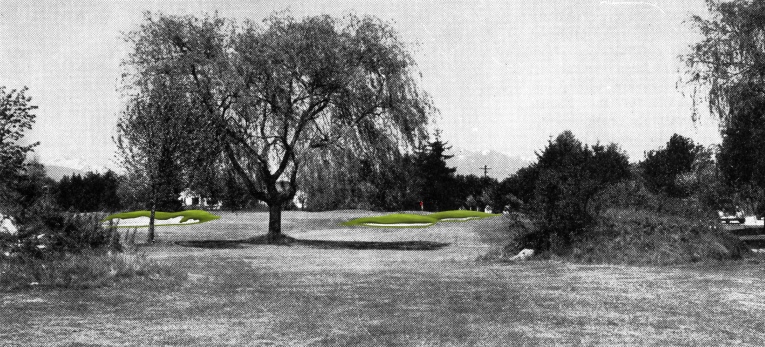

Another is the 15th at Fircrest, one of my favourite greens anywhere. The 15th is a staunch par 4, one of the longest on the course featuring another gorgeous Macan—designed green that fits the ground perfectly. But, with a relatively subtle spine running vertically through the centre of the putting surface, this predominately back-to-front sloping green falls off on three sides … right, left and front. It’s slick, and that simple spine makes any and every putt difficult to read.

The 3rd at Inglewood is another wicked one. A couple, three years ago we nearly doubled the size of this green, which had significantly shrunk over time. It’s still only about 4,000 square feet, with another vicious left-to-right slope. By regaining a couple thousand square feet of green surface, we restored some fringe hole locations that force golfers to think about angles of approach and using slopes on the green to their advantage at a hole that usually plays sub-300 yards, most days. Those fringe hole locations are tough to get close to, and the entire green, with its 1919 era slopes, is challenging to putt.

Is Victoria Golf Club an original Macan design?

Technically, no. Victoria has a fascinating history. The club was established in 1893, with a course laid out by its founder, Harvey Combe. Between 1893 and 1925, the course changed frequently, and dramatically. Club members played over three or four different versions of an 18-hole course on the same property between those years. It was in 1925 that Macan refined the course into essentially what it is today. So, there are remnants of all of those different courses out there, along with some definite Macan stuff, including the three-tier green at the 3rd hole, which is similar to the seventeenth at Waverley in Portland, also designed by Macan.

One of my favourite stories about the evolution of Victoria is about Macan’s green at the par 5 12th. Macan liked to design fallaway greens to encourage the ground game. This is how he built the aforementioned twelfth. Immediately, a number of Victoria golfers hated it. Apparently, Macan was a passionate guy, forcefully opinionated, and he naturally and vehemently defended his creation. There’s a funny letter from George Bigelow, a prominent member of the club, that reads: “Macan liked the old fashioned English – Scottish type of bump and run. But this was ridiculous. If you pitched on the (12th) green you would go over. If you pitched short, you stopped short. I was on the Green committee at the time, but we decided to wait until Macan died before doing anything about it because he would be mad as hell.”

Macan’s 12th green didn’t last long after his death in 1964!

Describe three of the most unusual features you’ve found on a Macan course.

Frankly, the most unusual stuff I’ve seen are things done post-Macan!

There’s an unusual story about the 5th hole at Inglewood. It’s a mid-length par 4, played up-and-over a hill to a steep, back-to-front sloping green that had deep greenside bunkers, right and left. The bunkers are still clear as day, they’re just grass hollows now. A very dramatic look when those hollows were filled with sand. During his 1935 consulting tour of America, on behalf of the PGA, A.W. Tillinghast told the club to eliminate those bunkers. If I recall correctly, his rationale was to cut down on maintenance expense during the Depression and make the hole play a bit easier. I show up at Inglewood a few years ago and immediately think, wow, those bunkers should be restored! Putting them back would remake a remarkable hole. But, restoring them was shot down in my Master Plan because it was Tillinghast — the famous A.W. Tillinghast — who thought they should go!

An unusual feature would certainly be Victoria’s two sets of back-to-back par 3s, at the 8th and 9th, and again at the 13th and 14th holes. The 7th was originally a par 3, too. There’s a great photo of that hole in George Thomas’ book, Golf Architecture in America. The club acquire some additional land during the 1970s and was able to lengthen the seventh to a par 4. It’s still a good hole, played along a cliff to the left, downhill to one of the most undulating greens you’ll see anywhere. It’s a great green that pre-dates Macan’s work at Victoria. We recently cleared a bunch of brush from behind the green, too, to restore a larger scale view of the ocean. The backdrop to the approach at the 7th is spectacular.

The 12th and 13th greens at Royal Colwood are unusual, too. Built in 1912 or ’13, they’re both huge greens that are literally draped over native hillsides. They’re beautiful lay-of-the-land holes to look at and admire, but there aren’t a lot of pin positions on either of those greens these days. I haven’t measured them, but they’re super steep. It’s one of those architectural conundrums. What do you do? They’re classic greens, on a classic course originally designed by a pioneering, now legendary architect. Something will likely have to be done to create more pin positions. Whatever that ends up to be will require creativity and precise surgery to ensure the results are appropriate.

Did Macan have a certain bunker ‘style’ or did it vary course to course? Did he make allowance for the wet Northwest climate (i.e. not have too much sand flashed up)? How do you decide what look to go with when you are working on his bunkers? Black and white photographs?

One of my favourite sayings is that no single rule can be applied to any true artist. This saying certainly applies to Macan, and his bunker work specifically. He definitely made allowance for the Northwest rain. You see a lot of grass face bunkers with flatter sand bottoms in historic photos of Macan—designed courses. But, there was also great variety in the types of bunkers Macan designed. Not only course to course, but different sizes and shapes, grass down and sand flashed on the same course … even the same hole!

Inglewood is a great example of this. Macan laid out Inglewood in 1919. The club brought him back three years later to bunker the course. The variety of bunkers at Inglewood in the course’s early days is remarkably beautiful and incredibly varied. And, again, the club has a treasure trove of beautiful historic photos that are really helping with our restorative-based work there.

Also, see the two images below. I found this historic photo of Macan’s course at Langara in Vancouver, which no longer exists. We colourized the bunkers in the photo, and have used this image as inspiration for our work at Manito in particular. It shows how Macan used two different bunker styles on the same hole! A more ragged looking bunker short of the green, and grass down at the green-side.

I’ve benefited from Macan’s bunker styling being so varied. My main goal, especially with the Seattle clubs, is to ensure the bunkering of those four courses — Inglewood, Broadmoor, Overlake and Fircrest — is just a bit different from one another, because distinctiveness is so important. Especially among nearby courses, even if they were designed by the same architect.

Macan was a contemporary of the great, pioneering architects of the 1920s and ‘30s era. How does his original works compare to that of Ross, Tillinghast, Mackenzie et al?

Well, he was definitely cut from the same cloth as those guys and he was a good player who’d seen and played the best courses overseas. A disciple of John L. Low, Macan was particularly talented at routing golf courses. Of all the changes I’ve seen made to his original designs, I’ve rarely seen any improvement to one of his routings. Victoria and Marine Drive have worked wonderfully for nearly a century on 78 and 90 acre parcels, respectively! It’s pretty amazing.

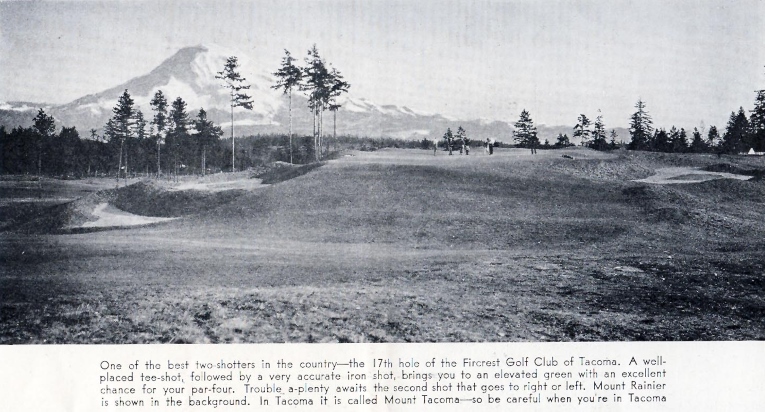

And, so-called “Macan greens” are notorious in the Northwest. He spent a lot of time thinking about his greens and working on the details of the putting surfaces. Again, anyone interested in golf architecture, needs to see those greens at Richmond, which proves he wasn’t afraid to be bold. Not only with his greens, but other features, too. The reverse Redan and Volcano holes we recently restored at Fircrest are incredibly bold, especially for the early 1920s. The 11th at Broadmoor, in Seattle, was an authentic Redan, too, that we’re hoping to restore next year. Macan knew and respected history, and the great courses and holes.

He worked on some spectacular properties, too, that have markedly changed. Originally, Inglewood and Broadmoor featured sweeping views of Lake Washington. But, trees have grown and houses have been built around both courses, so you only get glimpses of the water these days. At Manito in Spokane, the original clubhouse was on a bluff overlooking an undeveloped Latah Valley. It was spectacular. The 1st and 18th holes played along the valley’s edge, too. The club sold that property though, so there are no valley views at Manito today. And, Portland’s Alderwood Country Club was on the Columbia River. It was the first course west of the Mississippi River to host the U.S. Amateur, in 1937. Macan was proud of that. Alderwood’s now under the tarmac at Portland International Airport!

Macan’s courses have probably changed more than any others built during the pre-World War II era. In their original state, I think many of his courses compared favourably to those of his more famous contemporaries.

Why do you think Macan’s courses have changed more than others built during that era? Is it because he built features that people didn’t understand?

This is a good question that I’m not sure I have a definite answer for; but, I do have theories based on my research. There were different reasons for changes to Macan’s original work at different clubs and here are three examples:

Macan’s 1925 layout at Broadmoor, in Seattle, was one of the first in America to be designed in conjunction with a residential neighbourhood. Macan’s course there was pretty much intact until the early 1970s, when Bill Robinson rebuilt a handful of greens that we’re currently in the midst of restoring. I actually think it was proposed to redo the entire course with Robinson at that time, but something put that project on hold thankfully. Robinson became very well know in the Seattle area after finishing Sahalee in 1969. Sahalee kinda became a benchmark for a new style of golf architecture in the Northwest, which effected changes to Broadmoor and other Macan original designs.

Inglewood, just north of Seattle, hosted an annual Senior Tour event for a number of years and some of the most vocal pros constantly and loudly complained about some of the steepest Macan greens on the course. Those greens were built in 1919. We’re talking about a Tour event being played in the 1990s. So, those greens were unfortunately redone to satisfy modern green speeds and the preferences of those Tour pros. My Master Plan includes restoring the 1st, 2nd, 13th, 14th 15th and 16th greens at Inglewood, very carefully to ensure that they’re Macan—like but not ridiculously fast.

Then there’s Fircrest. I had a long time member, who’s not fond of the restoration work we’ve done there, tell me that he’s been a member of the club for 50 years and he doesn’t remember any of the stuff we’ve restored. Well, Fircrest was built in 1923. Fifty years ago was 1968. The course was 45 years old by the time this particular gentlemen joined. And, my theory is that most of the coolest features were gone by World War II. It was simply a matter of money and manpower that wasn’t available to properly take care of the course as it was originally designed. So, as happened elsewhere too, bunkers were removed, fairways were narrowed … the course shrunk, it became a shadow of its former self before anyone around today can remember. People came to think that its evolved state was Macan’s original design before we started doing our research. It’s been an interesting education process. Or, at least an attempt at educating people about the brilliance of Macan’s original work.

I also think, because Macan’s work was so regional in scope, he never developed a “legendary persona” like Mackenzie or Tillinghast or Ross, for example. Even Stanley Thompson. So, until Mike Riste started to explain to Northwest golfers who this guy was, there was comparatively little reverence for his work like there has been over the past 20—30 years for many of his more famous and revered contemporaries.

Which would have been his best course in its early days, when his original design was intact?

I think Macan would say Shaughnessy, in Vancouver. The course was completed during the late 1950s and hosted the Canadian Open in 1966, two years after Macan’s death. By the time he started planning Shaughnessy, Macan had been designing golf courses for six decades. Apparently, he felt that job at Shaughnessy was the culmination of everything he’d learned and thought about since doing Royal Colwood in 1913.

Early aerials of the course actually make me think of Augusta. Shaughnessy was wide, and there were few bunkers. But the bunkers that were out there looked meaningful. A number of them were centre fairway hazards that were immediately criticized. Macan’s response was: “The Old Course is plastered with central trapping. There is in the golf architecture world too much of the best authority for me to make any apology for advocating some centrally located traps. They invariably accentuate the need of accurate placement of the tee shot and increase the necessity of using your head as well as your clubs.”

There’s a fascinating section in Mike Riste’s Macan biography featuring the architect’s comments on the design of each hole at Shaughnessy. Among other interesting tidbits, he mentions stealing an idea for the 6th hole from a short hole at Royal Musselburgh. He also compares the gully in front of the 17th green to the Valley of Sin at St. Andrews.

Other than the routing, most of Macan’s original design at Shaughnessy is gone now. The course has become heavily treed, has been completely re-bunkered, a number of greens have been rebuilt, and many of the originals have lost significant surface area.

That is tragic! Speaking of center line bunkers, I am still blown away by the 6th hole diagram at Gorge Vale that Michael Riste sourced for his GolfClubAtlas July 2011 interview (click here to have a read). Clearly, Macan appreciated the importance of central hazards to create alternate playing routes. Yet, many such features are often removed over time. Is there an example of a hole where you have been allowed to restore hazards directly in the line of play?

That is a cool diagram that definitely illustrates Macan’s strategic thoughts and architectural philosophy. The sketch accompanied an article titled, Not “Just Hitting” That Counts. Macan advocated central hazards through his career. Sadly, I never got to see Gorge Vale before it was completely rebuilt. I get the impression it was a very good course. The property is beautiful, and Macan speaks highly of Gorge Vale in a number of articles.

In fall 2016, we installed a centre fairway bunker at Overlake’s par 4 16th hole. Overlake is one of Macan’s later courses, built during the early 1950s. Other than a routing plan, we don’t have a lot of historic materials to show us exactly what Macan was thinking for each hole at Overlake. So, as we continue work there, we’re trying to create a look and feel consistent with Macan’s work, and add some strategy based on my knowledge of his work elsewhere and his strategic philosophy. Overlake’s 16th is a long par 4 and it provided the width required to use a centre bunker strategy. Shoot the gap between the centre bunker and another bunker we placed on the left side of the fairway, and you shorten the hole plus gain an advantageous angle into the green. Bail right, away from the bunkers, where we’ve also widened the fairway significantly, and the angle into the green is comparatively awkward, over a greenside bunker, and the shot’s longer. Strategic architecture 101, right.

Of course, that centre bunker’s been met with mixed reviews. Personally, my favourite criticism is from golfers who simply say, “That’s exactly where I used to hit it,” which is of course the point.

Which of Macan’s originally designs is best preserved today?

Fircrest in Tacoma is pretty close to his original vision. And, it could be the best piece of ground Macan was given to work with. Fircrest is just down the street from Chambers Bay. Some bunkers are still missing, but the routing’s intact and only two original greens have been replaced over the years.

We’ve nearly completed a multi-phase bunker restoration project there, which also included restoring the Redan sixteenth and the Volcano hole … the par 4 seventeenth. A lot of tree work’s been done in recent years, too, with more planned. Fingers crossed.

The Green committee, and superintendent John Alexander, has been great to work with at Fircrest. But, we’ve been battling with a faction of members that don’t care for the course’s design pedigree nor some of the boldest features we’ve restored. I have to give the committee credit though. When I suggested restoring the Volcano hole, I was certain it would be turned down. Instead, the committee of the time unanimously voted to restore that hole first. I’m still not sure if that helped or hurt our overall cause.

Macan was a great admirer of what Mackenzie and Jones accomplished at Augusta National and Fircrest exhibits the same design philosophy. Again, the course occupies a great piece of ground that Macan took advantage of with a smart routing. Its greens are varied, extremely interesting, and provide a real challenge. And, like the original Augusta, there aren’t many bunkers at Fircrest. The terrain, the holes and the greens are so good, an overabundance of artificial sand hazards aren’t required. This is what Macan preached. He was adamant about ensuring his courses challenged the best and at the same time allowed everyone else to enjoy the game. Fircrest does that, perhaps better than any of his other courses these days.

Later in his life, Macan received a letter from someone asking for advice on becoming a golf architect. Macan responded, all you need to do to learn everything you need to know about golf architecture is read those two chapters in Bobby Jones’ autobiography, Golf is My Game, detailing Alister Mackenzie’s and his desires at Augusta National. I translate that as, if you get the routing and the greens right, the golf will take care of itself. Bunkers are often more of a decoration if you can creatively and effectively design to utilize the ground. It can be that simple, yet simultaneously complex.

Which other projects are you currently working on?

Wing Point Golf and Country Club approved my Master Plan last year. Wing Point’s a cool, casual, historic club on Bainbridge Island, about a 30-minute ferry ride from downtown Seattle. We’ll continue with more work there beginning this spring. The principal intent is to meld the style of two distinct nines built during different eras. Same at Town and Country Club in St. Paul, Minnesota, where we’ve started work over the past couple years and will continue this spring.

These are really fun jobs where I’m working with a couple passionate, talented golf course superintendents, Mike Goldsberry and Bill Larson. No contractors are involved. I’m doing most of the shaping work, along with those guys, with support from their in-house maintenance staff. We’ve done the same at Victoria and Kelowna, where we’ll also continue with more work this year.

I also have two Master Plans in development for Stanley Thompson—designed courses at Cutten Fields and Oshawa Golf Club in Ontario, Canada. Additionally, I’m working on improvement plans for Rivermead Golf Club, another historic club in Gatineau, Quebec, near Ottawa. And, I just started working at Briarwood Country Club near Chicago. Briarwood is Hugh Alison’s first course in the Chicago area, finished in 1921.

Talk to us more about your in-house approach at Wing Point and Town & Country. What benefits can a club expect by pursuing that route?

The biggest benefits are efficiency and economy. When I’m there, as the golf architect, doing the shaping myself, the project’s never held up waiting for the golf architect to show up from another city to “ok” a contractor’s work, or spend time changing things that didn’t come out right. I know what I want, so there’s no time wasted making time-consuming changes to work that’s already been carried out. This tends to expedite projects, comparatively, and also results in economy. The club’s also able to purchase all required materials directly, without a contractor mark-up. This amounts to big savings, too.

It takes a unique situation though, beginning with a superintendent and golf course maintenance staff that want to and like to be involved with the construction work, without the assistance of a contractor. Goldsberry and Larson have been great. So have Paul Robertson at Victoria, and Barry Evans and Lee Darnbrough at Kelowna. Justin VanLanduit at Briarwood and Bill Green at Cutten Fields will be great, too.

Tell us about those two Thompson courses, Cutten Fields and Oshawa Golf Club in Ontario, Canada. I have heard of neither. Would one guess that the architect who built Banff, Jasper, Capilano, St. George’s and Cape Breton Highlands built those two as well?

Neither course has the architectural stature of those you’ve mentioned. Not many do but they are beautiful properties, possess fascinating histories, and enjoy design pedigree.

Arthur Cutten was a Canadian-born businessman who made a lot of money as a commodity speculator in the United States during the 1920s. He spent a lot of time in Chicago, where he became friendly with the great amateur champion, Chick Evans. When Cutten came back to his hometown of Guelph, Ontario and bought the property that would become Cutten Fields, he wanted Evans involved with the design of his golf course. It was about 1930. Stanley Thompson was at the height of his career at the time, having recently completed St. George’s, Banff and Jasper. For whatever reasons, Cutten was smart enough to bring Thompson into the fold to collaborate with Evans. It wouldn’t surprise me if Thompson talked his way into the deal, either. That was his style, and he had a talent for it.

Thompson actually bought Cutten Fields during the 1940s. He lived and worked in what’s known as Dormie House, along the left side of the 16th hole. Funny, Thompson also made some significant changes to the layout during the late 1940s, subdividing parts of the back nine for residential development. It was strictly a monetary decision, because those changes didn’t improve the course. Still, Cutten Fields is a good course. With a couple tweaks to the back nine, in particular, it’ll be a very good course.

Oshawa dates back to 1906. The club’s original course was laid-out by George Cumming, the long-time pro at The Toronto Golf Club who assisted Harry Colt with the creation of that acclaimed Canadian course. Cumming was also a pioneer golf architect in Canada, with dozens of designs to his credit. For a time, prior to 1920, he had a design and construction firm in partnership with Stanley Thompson and his brother Nicol, called Thompson, Cumming and Thompson. About 1929, the Oshawa club picked up some additional land and hired Stanley Thompson to rework the course. There’s a neat map of Cumming’s original layout on display in the clubhouse along side a beautiful blueprint of Thompson’s proposed redesign.

Oshawa’s a really good course, too. Beautiful and fun to play for golfers of all abilities. We’re just looking at the usual suspects that need improvement over time … bunkers, mowing patterns, the tree situation, forward tees, etc.

If you could drive one restoration in Canada on a non-Macan course, what would it be?

Definitely, Hamilton. Harry Colt was back in Canada a couple years after designing The Toronto Golf Club to layout Hamilton Golf and Country Club, in Ancaster, Ontario. That was about 1913. Hamilton is a great layout over a tremendous piece of property for golf. All of Colt’s individual hole drawings are on display in the clubhouse, which allows us to see that a lot has changed at Hamilton over the years. Fortunately, Colt’s routing is basically intact, but the bunkering’s changed a lot and at least a handful of greens have been rebuilt since the course was originally constructed.

I’m a huge fan of The Toronto Golf Club. And, Martin Hawtree’s relatively recent restorative-based work there has been well-received. I think it’s very well done. If Hamilton is eventually given the same treatment, I think it’s a world top-50 golf course. The ground’s that good. The routing’s that good. The course features an excellent variety of distinctive holes. The course has a massive scale, too, comparable to many of the world’s best.