Feature Interview with Joel Zuckerman

October, 2008

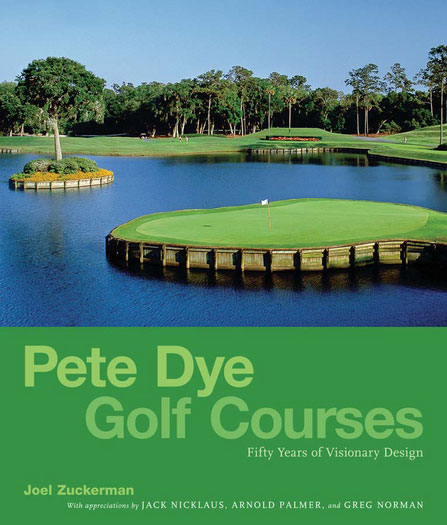

The Dye Family themselves selected veteran golf writer Joel Zuckerman to pen the recently-released Pete Dye â€Golf Courses: Fifty Years of Visionary Design, a 300+ page, 260-illustration, 65,000 word tribute to the game’s pre-eminent modern architect. Dye was inducted into the World Golf Hall of Fame in October, 2008, the very month the book debuted. Zuckerman has written for more than one hundred publications, including Sports Illustrated, SKY Magazine, Continental, and virtually every major golf periodical. The Dye Book is his fifth. Please visit www.vagabondgolfer.com for more information.

Joel Zuckerman with Pete Dye.

Pete Dye is arguably the most important man in architecture over the past fifty years. How were you selected to write this (important) book?

The Dyes have been fielding inquiries regarding the writing of Pete’s “Best Of” book for decades, and by more accomplished and experienced writers than myself, so I was very honored, and very lucky, to get this plum assignment. The short version: In the winter of 2006 I was talking to Pete’s older son Perry about another book project I was attempting to get off the ground. He asked me what was new in my world, and I told him my book on Charleston golf had just been released, and that his dad had written the Foreword. He asked me to send him a copy, and apparently was impressed enough with what he saw to ask me if I would be willing to take on the Dye Book. As you can imagine, I didn’t hesitate for long! I outlined a proposal as to how the book should be written, organized and promoted, we called the necessary agents, lawyers, etc. and I made my first official writing trip in mid-January, 2007, and submitted the manuscript in December of that year. Pete was ambivalent about the whole idea at first, he thought it was a project to be pursued after his passing. But as the momentum gathered and he saw how successful and enthusiastic was the support throughout the golf world, he lent his considerable influence to the project down the stretch, which helped immensely. I am happy and relieved to report that both he and Alice are very pleased with the final product.

When you set out to write it, you organized it by decades. In which decade did Dye build courses that you personally most enjoy playing? What is it about these courses that appeals to you?

The truth is the original plan was to go alphabetical, not by decade, and include the Next Generation Courses (the Dye sons, cousins, etc.) in the whole mix. A certain billionaire client of Pete’s told me in no uncertain terms that he would only support the book (IE â€purchase them in large quantities) if the book was chronological, and Pete’s courses were separated unto themselves. Turned out to be a great idea, which I guess is why he’s a billionaire, and I sit in front of a keyboard all day. Anyway â€I think Pete’s best work was 80s-and-90s (sorry I couldn’t narrow further) with the leading lights being (and here I’ll alphabetize as originally planned!) Blackwolf Run, Bulle Rock, Colleton River, Honors Course, Long Cove, Ocean Course, Old Marsh, Pete Dye Golf Club, the Stadium Courses (TPC and PGA West) and Whistling Straits. Generally speaking they are all a joy to play, though several are staggeringly hard, and beautiful golf landscapes, conjured from difficult, often execrable ground. This period was Pete at the height of his awesome creative power.

Completed in the early 1990s, The Ocean Course at Kiawah ranks with Dye’s best.

In general, what impact did his wife Alice have on Pete throughout his design career?

In a word â€massive. It was Alice who gave Pete her blessing to leave the insurance business, where they were both very successful, and take a flyer on golf architecture in the mid 1950s—an extremely fallow time to get into the business. Alice was a co-creator of some of Pete’s most storied designs, including Crooked Stick and the Stadium Course at TPC Sawgrass, and I’m sure most every GCA member is aware that it was Alice who came up with the concept of the island green at TPC Sawgrass â€undoubtedly the most famous (and controversial) of the 2,000 â€odd holes Pete has designed.

Apart from Alice, what have been the three greatest influences on Dye’s design career?

Bill Diddell, a mid-century architect based in Indianapolis, was an early mentor to the Dyes. Pete has also credited both Alister Mackenzie and Seth Raynor as influences. And perversely, it was Robert Trent Jones’ predilection for building up from ground level, and producing big tees, fairways and greens at Palmetto Dunes on Hilton Head that spurred Pete to go in the opposite direction at Harbour Town. He carved the course out of the ground instead of building it up, and used tiny tees and greens, just to be totally different. It was Harbour Town as much as any other early Dye Course that sent him on his way to widespread acclaim.

One of the world’s great par threes – the seventeenth at Harbour Town with its hard to find kidney-shaped green.

You had unfettered access to Dye for this book and there are a host of wonderful quotes from him scattered throughout. Given the time you spent with him what is your sense regarding TPC Stadium “ does Pete Dye of today prefer his original design there which was raw, sandy and more penal or does he like today’ glossier version that is both greener with more short grass and more strategic?

In a recent conversation, Pete insisted that apart from the softened and leveled-out greens, the actual routing, the “bones” of TPC Sawgrass, other than the recent lengthening of key holes, is much the same as what it was at the beginning. He also informed me that not only was Jerry Pate’s winning score under par in that first Tournament Players Championship, (his stroke average was 70 for the four rounds) but that back then there was a Pro-Am before the tournament. Pete himself played with Ray Floyd, who was ready to post 66 with a par on the last. (He hit it in the gargantuan lake left of the 18th fairway, and settled for 68.) So he maintains that the course, even in its earliest iteration, was manageable by the game’s best. But one thing he admits: Over time, the precipitous mounding, which was shaggy and rustic to begin with, has been softened, flattened somewhat and manicured, allowing for more spectator access. Because he enjoys the fact that people get to come to his creations and watch the game’s best players up close and in-person, and the current mounding affords more access to greater numbers of paying customers, he likes the modern day version better.

In some ways, the do-or-die seventeenth at TPC in Florida doesn’t quite fit with the rest of the strategic course and yet it may be Dye’s single most famous hole. Where do you place it within the galaxy of sub-150 yard one shotters that Dye has built? Top five? Or lower because you wouldn’t necessarily enjoy playing it on a weekly basis?

I’ve only played the hole twice. Once I hit the green and made par, once I dunked it, then three-putted the provisional for a triple. In my opinion, one of the game’s mysterious appeals is it’s a combination of relaxing and nerve-wracking, and #17 Sawgrass is a prime example of the latter. Though my experience at Sawgrass is limited, I have had occasion to play a similar hole dozens of times â€the 17th at South Carolina’s Secession Club, laid out by Pete Dye, although the final design credit went to Bruce Devlin. This is also an island green par-3, completely surrounded by marsh, sometimes playable from within, but sometimes not. Just as at Sawgrass, the prospect of hitting (or missing) this elusive target is never far from mind as a round progresses, and it’s a decimating blow to ruin an otherwise decent score by doubling, tripling, or even taking an ËœX’ at the penultimate hole. I like #17 Sawgrass very much, as I also like the 17th at Harbour Town, the 2nd at The Golf Club in Ohio, the 5th and 7th at Teeth of the Dog, the 13th at Crooked Stick, I think it’s the 12th at Long Cove, also the 12th at Colleton River. They are all memorable par-3s, though several I mention are longer than 150 yards.

What are some examples of Dye’s innovations that have helped to change the direction of golf course architecture?

One thing I know Pete is very proud of, and a facet that doesn’t get too much publicity, is the fact that he’s helped pioneer the use of recycled water on a golf course. Old Marsh in Florida and the Kampen Course at Purdue University in Lafayette, Indiana, are two excellent examples of his innovative water recycling techniques, where water that’s put on the course goes underground, is stored, pumped back into the irrigation system and re-used again. The Dyes are also adamant about the fact that they almost never engineer forced carries to the green, with the exception of par-3 holes, where a golfer using the appropriate tee box for their ability level (and, as Pete points out, with the benefit of a tee beneath the ball) should be able to fly their shot up and over the hazard. He also likes to leave the green site on the original land contour, but give the appearance of elevation by scooping out the earth immediately in front of the green pad.

Though out of sight, the recycled water system at The Ocean Course at Kiawah is state of the art.

Given his love of links golf, did he ever pursue building a course in the United Kingdom?

No, not seriously. There were opportunities over the years, but because Pete is so hands-on, and spends so much time on the job site, he and Alice didn’t want to commit to living overseas for long stretches of time.

What are your three favorite sites with which Dye was given to work?

The Honors Course near Chattanooga comes immediately to mind. It is an absolute study in serenity, a delightful mountain-ringed valley, both gorgeous and incredibly peaceful. Old Marsh is a very cool site also, truly the swampland primeval down in Palm Beach Gardens, Florida. And here’s one out of left field: Promontory, outside of Park City, Utah. 30-mile views of the whole valley on the way out, and then diving into a twisty canyon on the way home. And I’ll add one more that I would bet not one of fifty GCA-types have ever seen â€Luana Hills on the island of Oahu. It’s barely 30 minutes from the international airport, but it’s a quirky, 7/10ths scale, flora-and-fauna filled rainforest that could’ve been the setting for Jurassic Park. You wouldn’t want to play it often, and you could make an argument that “one-and-done” is as much as any sane golfer needs to see, but it’s a highly unusual golf setting,

Conversely, Pete Dye has transformed many a flat site into a golf course of great land movement including Whistling Straits, Colleton River and Barefoot Resort. As with any artist, not all works turn out equally well “ in studying his courses, can you determine when such massive earth movement worked the best and when it didn’t (i.e. was it the shaper, the size of the budget, etc.)?

Pete’s philosophy in this regard is similar to most architects, in thinking that a great site requires little earth moving. But throughout his career, he’s been asked to build courses on exceedingly difficult terrain. He’s particularly pleased with how the Straits Course came out. Owner Herb Kohler wanted it to look like Ballybunion, though it was runway-flat to begin with. (In fact, there was an old military runway on site!) He claims The Ocean Course was initially a swamp, and drainage was an incredible headache at Sawgrass, where the lake left of the 18th is literally six feet below sea level. He spent six months of initial construction attempting to drain that lake, and all it took was one massive rainstorm, and Pete was back in a motorized skiff, touring practically the entire site, trying to figure out what to do next. Those are great examples of his earth-moving acumen. Courses on his resume that also required plenty of earthworks, but might not be quite on the same level aesthetically, include western Pennsylvania’s Nemacolin Woodlands and the new Pound Ridge course in Westchester county, both of which are extremely rocky sites. TPC Louisiana was also a tricky site, and was ravaged by Hurricane Katrina a year or two after opening.

Apart from TPC Stadium course, what site had perhaps minimal potential and yet from it emerged a great course?

I was extremely impressed, blown away might be a more accurate description, with the Pete Dye Golf Club in Bridgeport, WV. I’ve never seen (nor have any desire to see) a strip mine, but I understand it’s as hideous a landscape as can be imagined. The fact that Dye turned a smoldering slag pile of deteriorated coal, rusted, ruined equipment, scraggly, withered vegetation, and all manner of detritus into this wonderful, scenic playing field is in my mind the prime example of Pete “turning nothing into something.”

Numerous men who worked for Dye have gone on to their own successful design career including Tim Liddy, Bill Coore, Tom Doak, and Rod Whitman. Indeed, some of these men are now building courses that are regarded even more highly than Dye’s own work. Is there any accounting for why Dye spawned so many outstanding architects?

Pete’s theory on this subject is that, unlike other high-profile architects, he spends a tremendous amount of time in the field, as opposed to drawing plans in an office. Because he is actually out on the building site continuously, and all day long, as opposed to making cameo appearances, it allows him to interact and guide crew members in a manner that’s impossible for architects who are rarely on site. And because Pete can actually build, not just design, a golf course, his expertise extends to laying irrigation lines, driving heavy equipment, contouring greens, etc. This “nuts-and-bolts” expertise is what he has been able to pass along to his associates over the decades, which have allowed them to learn all the actual, as opposed to theoretical, skills needed to build a golf course. The other theory is even simpler â€The man’s been at it for 50 â€odd years now, so just by his longevity, he’s had the opportunity to influence and teach several generations of would-be architects, some of whom have gone onto great prominence themselves.

What is your favorite Dye risk/reward par three, par four and par five and what do you like so much about each?

So many choices! I’ll mention two totally different par 3s: The naturalistic 14th at The Honors, relatively short, bunkered left and right, with waving fescue grasses between tee and green. Apparently Pete wanted a huge tee-to-green bunker, but was overruled by autocratic owner Jack Lupton, who chided Pete by saying the Honors wasn’t to be a Florida-type golf course. I also admire the island green par-3 15th at the Wolf Course on the Las Vegas Paiute Reservation. It’s tougher than Sawgrass or PGA West’s versions, owing to the triple-tiered green. As for par 4s, I always enjoy the short-but-tough 13th at Harbour Town, with the green ringed by sand and fortified with railroad ties. The dogleg 5th at Blackwolf Run’s River Course, with its elevated tee, is fantastic, as is the sterling 10th at the Pete Dye Golf Club. As for par 5s, I again must mention the Pete Dye Golf Club, I think the 5th hole, where the aiming point off the tee is the towering smokestack in the distance. Another par-5 beauty comes early in the round at Oak Tree in Oklahoma, where the third shot to an elevated green must be struck just so, as a hair long bounds over the back, a touch too delicate and the ball will carom off the fronting bank, and thirty-odd yards back down the fairway.

The Teeth of the Dog is a wonderful course that is in the low profile mold of other Dye courses from that period including The Golf Club and (at that time) Crooked Stick. Dye Four represents Dye at his busiest, moving land every which way. Do you think Dye Four will stand the test of time nearly as well as The Teeth of the Dog?

No, I do not. Personally, I am a fan of this golf course, though I am well aware that many are not. Teeth of the Dog is in a class by itself, one of Pete’s best, and certainly one of his all-time favorites, not just for the layout he conceived, but also the fact it was such an economic boon to the DR at the time of construction. But I find Dye Fore to have some large-scale charms of its own, including some wonderful dogleg par-4s on the nine facing the sea, and some precipitous climbs and descents on the nine near the Chavon River. I’m curious to see the end result of the additional 18 that’s planned for the site, when the two existing nines will be bifurcated, and then each join one of the new nines under construction.

In a Feature Interview in December 2000 on this site, the question was posed; “Many consider the low profile The Golf Club and Casa de Campo Cajuiles Course as your two finest designs. Can you contemplate returning to that design style in the future?” He responded, ËœThought I had.’ Any idea to what course(s) he was thinking about? I would dearly love to play any low profile, rustic course that Dye has built in the past decade but I am unfamiliar with any.

The Bridgewater Club and his redesign of a Bill Diddell course called Woodland CC, both in greater Indianapolis, would qualify. Also the Dye Course at PGA Golf Club, and his recent redesign of the Gasparilla Inn Golf Course, both of which are found in Florida, are two more courses built mostly low to the ground.

Is there a course of his that you think has been unfairly stereotyped?

My first thought here concerns perhaps Pete’s most notorious House of Horrors â€the Stadium Course at PGA West. The famous line by the great sportswriter Jim Murray summed it up in the minds of many: “You need a camel a canoe, a priest and a tourniquet to get through it.” The pro met me after my round behind the final green, and asked me how I did. I told him I managed to keep it in the 80s, but hadn’t lost a ball. He literally stopped in his tracks at that admission, and told me it’s only a couple out of every 100 players who finish a round with the same ball they started. It doesn’t matter if they shoot par or close to it, it’s almost inevitable you’ll lose one into the water at some juncture. It goes to prove you can scrape and skid it around, as long as all those wrong hits end up in the right place. That said, I might have replayed the course that afternoon and lost a half-dozen or more. In my opinion, other courses that are more playable then their reps include The Straits Course at Kohler, and Oak Tree Golf Club in Oklahoma. And on the opposite side of the ledger, his recent redo of a mostly-toothless resort course called Sea Marsh at Hilton Head’s Sea Pines Resort is now an ass-kicker called Heron Point. Prepare to suffer!

There are seventy-five Pete Dye courses featured in the book and another dozen in the Next Generation – P.B., Perry, cousins, etc. – section. However, Dye has had his hand in over three hundred courses. How were the decisions made as to what to which of the lesser known courses would be included versus which had to be left out?

There were plenty of tough decisions that played out during the entire writing process. There were last-minute additions to the text–courses like Urbana CC in Ohio, which is the original 9 â€holer (now 18) that Pete’s dad Pink Dye built on his wife’s family land, and that Pete took care of as a kid. Also â€Virginia Tech â€which Pete asked me to include, owing to his fondness for collegiate courses. There were last-minute deletions, including a number of courses I traveled to and played. These include Robber’s Row, on Hilton Head, not far from my home in Savannah, which Alice nixed because it’s a re-design of an old George Cobb course. There was Trump National in Rancho Palos Verdes, California, originally called Ocean Trails, which was where part of the 18th fairway crumbled into the sea, bankrupting the Zuckerman Brothers, of all people. The Donald swooped in and bought it after that, and made some design changes, including one of his signature waterfall abominations. There was Harbour Trees, in Indy, which got left on the cutting room floor because of too much representation in the Dye’s hometown, and a lesser light called Little Turtle, not far from the Golf Club in Columbus, Ohio. There are chapters on courses I wished I could have played (Big Fish, in the far-reaching wilds of Minnesota) and chapters on courses that I could have easily eschewed (but you’ll have to torture me to find out which ones!) In short â€we covered practically all of the significant milestones of Pete’s career, and included many lesser-known but enlightening examples of his work.

Many of Dye’s courses achieved fame by hosting events on television. Indeed, page nine in your book lists the numerous important events that have been contested on his courses. Among his courses that keep a quieter profile, do you have several particular hidden gems (please exclude The Golf Club as its lofty rankings by every major publication speak for themselves)?

Of the non “household name” courses I enjoyed during the writing of the book, I would mention The Fort in Indianapolis, a “kill or be killed” up-and-down ramble through thick woods and fescue, on the grounds of an old military installation called Fort Benjamin Harrison. Fowler’s Mill outside of Cleveland is a pristine nature walk, very quiet and pastoral, albeit mostly the work of Pete’s late brother Roy Dye. I will also mention a course not far from my Savannah home called the Ogeechee Golf Club at the Ford Plantation. The front nine is a traditional Lowcountry design, but the back nine is entirely different, an open, windswept routing through the old lettuce fields at Henry Ford’s winter residence. The dichotomy between front and back (not to mention the dearth of play â€maybe 8-10 golfers a day, on average) make it a very interesting venue.

What is Dye’s lasting legacy?

In my opinion, Pete is the most important and influential architect of the modern era. This website’s aficionados are a breed apart, but the average, 10-or-20-rounds-a-year golfer would be hard pressed to identify more than a single course produced by Nicklaus, Fazio, Jones, or dare I say it â€Doak. But Pete’s six or eight most famous creations (no need to list them here) are familiar to even casual players. One other salient point: Pete is infamous for no computers, blueprints, topo maps, CAD drawings, or anything of the sort. It’s a peculiar brand of genius that allows him to see golf course routings in his head, in his mind’s eye, by walking and walking the land. He’s a throwback and a true savant. We won’t see the likes of him again anytime soon, if ever. Let me share one final comment from Pete, which sums up both his legacy and his attitude towards his profession. He recently said to me, “I get the biggest kick out of going to a place where no golf course seems possible, whether it’s a cornfield, a swamp or a rock pile. I somehow make a golf course out of it, and a couple of years later, there’s a high-profile tournament being played there, and it becomes known all over the world.”

The bookstore edition features the cover above of the island green at TPC Sawgrass. However, I understand that there are ~ thirty different covers available. How did this unusual marketing decision come to pass?

Let me put it this way: Harbour Town didn’t want an Ocean Course cover. The Ocean Course didn’t want a Whistling Straits cover. Whistling Straits didn’t want a Teeth of the Dog cover, and so on, down the line. There was tremendous interest in participating in this one-of-a-kind project, and dozens upon dozens of Dye Courses wanted be included. Those who opted for custom covers to showcase their own facility included the big-name resorts, mentioned above, lesser-known resort, or public courses (Brickyard Crossing, The Fort, Gasparilla Inn, Barefoot Landing, Nemacolin Woodlands) well-known private clubs (Crooked Stick, The Honors) not-as-well-known-private clubs (Old Marsh, Long Cove, Colleton River) low-key private clubs (Dye Preserve, Delray Dunes, Fisher’s Island) and up-and-comers that wanted to make a splash in their own market. (La Estancia, French Lick) The end result was a ton of extra work for the design team, and lots of organizing, vetting of images, etc. But it also means many thousands of additional books sold in advance to the individual clients that wanted their own course showcased, and dozens of different options for the collector, or someone predisposed towards a certain golf course.

Joel Zuckerman has agreed to make a special holiday offer to all GolfClubAtlas.com readers, including personalization, a custom cover, and your choice of an additional ‘thank you’ gift for purchasing directly from the author. Click here for details:

http://www.vagabondgolfer.com/GCA%20letter–2.pdf

To purchase the book from the author without any rigamarole, visit WWW.PETEDYEBOOK.COM.

The End