Feature Interview with Richard Mandell No. 3

November 2007

Richard Mandell, a golf course architect in Pinehurst, North Carolina, unveiled this summer his new book called Pinehurst ~ Home of American Golf (The Evolution of a Legend). Richard is a GolfClubAtlas.com regular contributor, but has been quiet here the past four yearsas he wasresearching, writing, and publishing his new book. Please refer to his two previous Feature Interviewsin March, 2002 andMay, 2005 for biographical information.

The stunning second green at Pinehurst No. 2 as seen in the late 1930s.

How did you come up with the idea for ‘Pinehurst ~ Home of American Golf’?

One day I was reading Gleanings From The Wayside, the third book in a trilogy of A. W. Tillinghast’s writings put together by Rick and Stuart Wolffe and Bob Trebus, and I noticed an aerial view of Pinehurst along Highway 5. It was a shot that you wouldn’t look at too closely unless you lived there and I noticed that one hole in particular (today’s second hole of course No. 3) was going in the opposite direction from where it should be going. Driving by a few days later, I pictured the hole [going in the direction] I saw in the picture and the green site was a very natural plateau.

That basically got me thinking about how the Pinehurst golf courses have changed over the years. The basics of No. 2 were pretty cut and dry but the other courses were not. My initial thesis for the book was the evolution of the golf courses of Pinehurst and how golf course architecture’s evolution in Pinehurst mirrored the evolution of golf course architecture in the rest of the country. At that point I started my research.

Previous books on Pinehurst have contained little detail yet the amount of information on Pinehurst is vast. Your book contains over 300 photographs and illustrations, many of which have rarely been seen by the public. How did you go about your research and what were your best sources?

Even though I had the thesis idea in my head, the number of directions I could go in at that point was overwhelming to say the least. The only way to move forward at that point (as in many creative processes) is to just do it. I started the research not with a particular question to answer. Instead, I just started with resources, beginning at my house. I started taking notes from what little was written about Pinehurst and the area as well as my own golf course architecture books. I put all my notes on 3′ x 5′ cards with a subject heading for each. Those subject headings really just evolved as I began the research. From there, I took stock of the subject headings and the book topics began to take shape.

The bulk of my research began and ended at the Tufts Archives in the Village of Pinehurst. The Archives is located in the back of the Given Memorial Library and was started in the seventies as a depository for all the records left behind by the Tufts family concerning Pinehurst. It has evolved into the primary location for all of Donald Ross’s drawings as well as other information regarding the sandhills as a whole. But the primary focus is Pinehurst.

For the first two years of the project I went through a wall of boxes about fifty feet long by nine feet high. Inside those boxes were thousands of manilla folders with letters, newspaper accounts, stories, personal remembrances, etc. My fingers touched everything. That is a daunting task, but to make matters worse was my struggle to keep focus on the task at hand and not wander into something else just through curiosity. The Tufts Archives is ‘fascination defined’, especially for the typical GCAer. I ran across many interesting tidbits about not just my subject but golf course architecture in general. I started research in August of 2003 and finished the initial round in March of 2005 or so. From there I went to the Southern Pines Library and the Moore County Library. At that point I had to just stop and take inventory of what information I had. In other words, I had to start writing the damn thing. But not before I started interviewing people for first hand experiences. I interviewed about fifteen to twenty people throughout the process, including Peggy Kirk Bell and a few ninety year olds, two of which knew Donald Ross personally and were never interviewed before on the subject of Ross, Peter Tufts and Rod Innes.

The whole picture and illustration element wasn’t really addressed until I had finished the manuscript (which was February of 2007). As I did my research I ran across numerous photos and drawings of which I made mental notes to include in the book at the time, although I couldn’t really focus on pictures until I had a solid text in hand (the photos were to supplement the story).

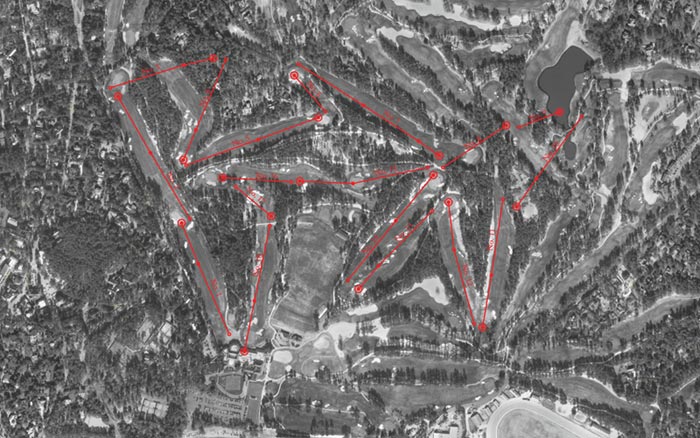

One illustrative aspect I focused on before the text was complete were the overlays, of which thee are seventeen. The overlays are simply historical drawings of the Pinehurst courses transposed on top of a present-day aerial photograph of the resort. As part of my research in order to tell the story, I had to understand where these golf holes began and evolved, and at the same time it was the best way to illustrate the evolution of the courses to the reader. I gathered together every layout of Pinehurst over the years, beginning with the first nine holes from 1897 and concluding with the five courses as they laid in 1961, scaled them as best as possible, and overlaid them on my aerial. This helped reveal the changes to the courses better than any narrative could and was a painstaking task.

Most of the photos came from the Tufts Archives and the people there were very accommodating. I had the opportunity to sift through over 15,000 images. Surprisingly, it didn’t take more than a few days to go through that many photos. I made a conscious effort to avoid the typical photos that everyone has seen again and again and only chose photos that were never used before. An advantage I had was that every day over the past four years (and continuing today), the staff at the Archives was consistently cataloguing images stored in the basement there and were never before seen by the public.

The remaining photographs came from all the other golf courses in the area and everyone was very generous. Of course, it makes sense for them to do so as it is a form of marketing. Basically the golf courses in the book that I focus on were the courses where the most information was available or I interviewed someone who had a vital part in the history of that course. The same is true of photographs. I used the best available and there were many. My initial ‘page budget’ for the book was 300 but I found so many ‘must-haves’ that the book grew to 384 pages.

Please describe the initial 5,000 acres that James Tufts purchased.

You know, I have to admit that I didn’t get to see that land. Although I feel one-hundred years old, I’m only thirty-nine. My description is really just second hand. All joking aside, that first acreage was desolate. It was originally a full Longleaf Pine Forest that was clear cut for timber as well as other resources from the trees (pine tar and pitch used for many purposes). The Page family from Aberdeen (a town bordering the southern side of Pinehurst) came from Raleigh in search of these trees and upon depleting them were left with a wasteland of sand. The land was so poor that people described it as just a binding of the world.

Legend has it that the entire 5,000 acres was clear-cut and that may be true to a certain extent, but there was plenty of land that was still forested. This is clear in many of the early photographs of Pinehurst which show treelines in the distance. The story is good, though. The land was, and still is, primarily sandy soils and in most places is pure sand, which makes for great golf. The cleared land was also very conducive to building golf holes as well. The topography was very rolling (again a very nice feature for golf). But the irony of the perfection of this land for golf is that it had no bearing on why Pinehurst evolved into such a golfing-rich region. In fact, one of my earliest theses for the book was to prove (or disprove) the advantages of sandy soils in the evolution of the golf courses of the sandhills.

The truth is that sandy soils had zero influence on the early evolution of golf in Pinehurst and really still has very little influence today. That doesn’t mean that the presence of sand wasn’t helpful because we obviously know that golf courses built on sand as opposed to clay are going to be much better. But the fact is the evolution of Pinehurst as the Home of American Golf was purely economically driven.

Apparently, few people wanted to come to a resort where the majority of visitors have some sort of contagious disease. Ironically that little nugget still holds sway today. See, James Walker Tufts (who started Pinehurst) initially began his venture as a getaway from consumptives to recover from their ailments (consumption is now more commonly known as tuberculosis). He clearly didn’t get a feasibility study done and early on discovered consumption was indeed contagious, minimizing the resorts attractiveness.

Only through tremendous dumb luck and opportunity did his resort gain traction as a golfing paradise. After realizing the consumption thing wouldn’t work, Tufts switched gears and focused on ‘recreational pursuits’. The legend of observing people swatting golf balls in the dairy fields is true and Tufts seized on the idea. At the time, golf was virtually unknown in the United States. The Tufts continued to build based upon staying ahead of the curve and everyone else followed, primarily to sell real estate. Sandy soils had little influence on the success of the area, though. Unlike a place like Bandon Dunes where the site (and soils) drove the development of golf, the opposite was true in North Carolina.

What were the influences on Dr. Leroy Culver when he laid out the first golf course in Pinehurst in 1897?

There is very little known about Dr. Leroy Culver other than he was the resident physician at the Piney Woods Inn in Southern Pines at the time of his work. He previously was the medical chief of the Department of Public Charts of New York City. There is no documentation as to why Culver was asked to lay out Tufts’ first nine holes other than he must have been one of the few in the area who was familiar with the game of golf at the time. Early accounts lead one to assume he was a golfer who had previously trekked to St. Andrews. In fact, a local paper of the time described Culver’s goal to ‘bring about a course similar to the St. Andrews Golf Links.’

Culver himself refers to Scotland (mostly in terms of lack of trees) in describing his efforts to compete with the first golf courses of the northeast:

‘Resorts of the North can boast of grass covered meadows, dotted here and there with trees. To be sure groves of trees beautify the landscape, but mar the joy of the game for him whose ill-directed drive has landed his ball in the midst of the foliage. This lack of appreciation of the beautiful in nature is a feature of golf. No matter how artistic or picturesque with woods and ravines may be the course, the golfer only sees in them so many more or less insurmountable Ëœhazards’ and Ëœbunkers’. We are happy to say that there are no obstructions other than those placed there in connection with the few hills met with on our course, and those lend interest to the game. There are no links in the South to be compared with those at Pinehurst, and they will prove the great magnet of attraction to lovers of the game.’

That’s all I’ve got on Culver.

What one Ëœfind’ surprised you the most during your research?

It was probably a Ëœnot found’ that most surprised me and that was the history of Southern Pines Country Club. Let me first say that odds are it is a Donald Ross course, but in the course of all my research I found zero documentation to that effect. That’s all. I certainly wasn’t looking to disprove that Ross didn’t design the course, I was just doing my due diligence on a few errors and inconsistencies regarding Southern Pines. For instance, it is common Ëœlocal knowledge’ that Southern Pines Country Club was built by the Town of Southern Pines in the late twenties. But the Town only owned the course from 1946 – 1951. They did manage the course from 1941-1946, but it was privately owned prior to that. The Town did initiate the construction of a golf course in 1906, but never followed through. I’m guessing that they found some individuals to carry out the task.

I have combed over the Town of Southern Pines Commissioners Minutes from meetings beginning in April 1906 all the way to 1950 and found no reference to Donald Ross. Nor did I find anything else in other places. On the surface it seemed odd because I found concrete evidence to Ross’s involvement in Pinehurst as well as Mid Pines and Pine Needles, yet nothing at SPCC. A few months ago someone came across a marketing pamphlet of Ross’s from the early thirties which lists Southern Pines as thirty-six Ross holes. In some ways that could be enough evidence, yet not necessarily. Another surprise is the expansion of the club from eighteen to twenty-seven holes. I found nothing as to when the next nine holes came on line and at some point nine more were cleared, but never built. I go into more detail on this subject in the book.

What was Ross’s role when he came to Pinehurst?

Donald Ross came to Pinehurst strictly as a golf professional. His role was to give lessons, make clubs, and run day to day operations. But as was customary of the era, the golf professional was the logical one to turn to when it came to design as well as maintenance of a facility. This was true before Ross arrived because the first pro, John Dunn Tucker, was asked for design input regarding the first nine holes. I surmise that from the time Ross first arrived in 1899 to about 1906, any design decisions were a group effort by Ross, Leonard Tufts, Tucker for a period, probably Culver to a degree, and the first official greens keeper at the time, Edwin Sheak.

Donald Ross clearly became the sole reference for design when he expanded No. 2 to eighteen holes in 1907. The first nine holes (mostly par three distances) were probably a group effort. Pinehurst No. 3 was Ross’ first complete solo effort and was started in 1907. It was that same year when Frank Maples arrived in Pinehurst and from then on, those two were the primary people involved in design and construction of future Pinehurst work until their deaths in the late forties.

What prompted Ross to make so many changes over the years at Pinehurst?

Aside from experimentation, the changes Ross incorporated over the years were in response to the ability to create a playable stand of grass. In the beginning, the fairways were a fifty-fifty hodge-podge of sand and native grasses. The tees and greens were strictly sand. Because of the sandy composition of the area it was much tougher to grow grass in Pinehurst than the northeast or the British Isles. This was in part because of temperatures and also because of a lack of organic material in the straight sand. As a result, lies were questionable at best. As early as 1913, Leonard Tufts, Ross, and Maples began experimenting with grasses. Here is a quote from Leonard:

‘I shall never forget the thrill I got when in looking out of the car window coming up from Florida, I saw several real sods of Bermuda, ten feet square or more in a sandy, dusty, mule pen, where the mules were turned out on Sundays and when not being worked. From this glimpse I knew with plenty of animal manure we could make a sod. That spring and summer we manured heavily and reset spots to Bermuda and it worked but we had to feed several carloads of cattle every winter for the manure and we had to manure and reset such holes every three or fours years.’

Simple fertilizer really gave them a jump start that for the next twenty years saw slow progress as the Bermuda became established. As grass replaced sandy areas, the golf courses slowly evolved from penal to more strategic and formal sand bunkers became distinguishable. They had most success in approaches and then tees and finally greens. One interesting note is that in 1927, Ross built a new alternate green for the third hole of course No. 2. He built a new grass green on the site of the original putting surface and a new sand green just over some mounds to the left to see how the golfers would respond. In 1934, he added experimental greens on the first and second holes as well. By the following year, everyone was confident enough to convert all the greens to grass. That allowed Ross to completely re-design the putting surfaces to what many consider the ‘typical’ Ross plateau greens.

How authentic is No. 2 at this point? What is the evolution of the greens at No. 2?

Pinehurst No. 2’s routing in 1907 is seen in red and is overlaid on the playing corridors of today.

Pinehurst No. 2 is the most authentic of all the Pinehurst courses. The routing of the course has not changed since 1935 (when today’s fourth and fifth holes were added. They previously were the first and ninth holes of the employees course). Since 1935, courses 1, 3, and 4 have all been altered not only with routing changes, but also by different architects. No. 5 was added in 1961 and prompted many of the routing changes to 1, 3, and 4. No. 2 was spared any routing alterations not because it was sacred, but because it was a bit more isolated than the other courses and there was little advantage to routing changes in the expansion process once the employees course holes were added. In fact, the addition of those holes in 1935 allowed the course to remain even more compact and insulated from potential poaching for other courses.

Now the greens have changed immensely from the original putting surfaces of No. 2 (which is true of most golf greens the last one-hundred years). This isn’t necessarily the case since Ross’s passing, though. There is a difference. The appearance of No. 2’s greens from 1907 to 1935 is much more dramatic than their evolution from 1935 to today. I would guess that the greens are at least 75% accurate to 1935 as they sit today, possibly 80%.

Originally these greens were sixty foot square flat, clay surfaces. Starting in 1915, Ross began incorporating contours. 1935 was the year he converted them from sand to grass and created much of the contour that we see today. Many counter that the greens weren’t nearly as severe in 1935 as they are today. They may be a few inches more severe in places but for the most part they are like Ross built them back then. A few inches here and there, though, can mean the difference between a manageable 4% (with today’s speeds) to a ridiculously fast 7% or worse.

The marked difference between Ross’s greens and the ones golfers putt today is what makes these greens so severe. In Ross’s day, there was a sort of shelf around the green edges of the greens (as putting surface) that was shaved off with a bulldozer by the Diamondhead organization in the early seventies. This act effectively removed about 15% of the putting surface and without the shelf, a mis-hit shot will roll of the green quicker and more often than before. There is also the issue of faster green speeds to complicate matters further.

This late 1930s photograph of the eleventh green at Pinehurst No. 2 shows how the putting surface was once level with its surrounds.

We sand bunkers have changed over the years as well. Most people attribute the grass faces of Pinehurst No. 2 to all Ross work, which is very false. He had many different looks, but one common thread was to ensure some visibility of the sand. That is clearly evident in his design work from the thirties at No. 2. The grass-faced, flat sand bunkers were a result of Henson Maples changing the bunkers to improve his maintenance regimen, nothing else. Unfortunately that was translated as a Ross feature somewhere along the line, a feature that is often incorrectly ‘restored’ to this day at other Ross courses.

Why did No. 2 come to prominence over the other four courses?

I address that issue in the After word of my book. From an architectural standpoint, No. 2 is the most authentic of the Pinehurst courses which lends credence to its status. But the leading reason unfortunately lies in the one characteristic that we architects face every day – especially in the struggle to keep the great old courses up to par with the newer layouts – and that is length. The simple answer is that No. 2 had the length that the other four courses never had. Because of that, No. 2 was always chosen for the big tournaments; not just the North & Souths, but the Ryder Cup and the PGA Championship as well. The presence of length led most to its prominence. Because of its length (as well as its relative isolation from the other courses) it was spared changes. This led to the decision not to develop homesites along its fairways like the ones that exist on the other courses, although at one point Diamondhead planned for another hotel and condominiums along No. 2. Luckily that never transpired.

How would you characterize the Diamondhead era (1970-1984)?

Diamondhead really has gotten hammered by everyone and they did do some ill-advised things to Pinehurst when they took over. From a business standpoint, they transformed Pinehurst from a sleepy resort to a residential development. This was done out of necessity as Pinehurst would never have survived without the influx of money that was brought in on the development side.

The fact is that the Tufts family would have done the exact same thing if they had the finances to do so. In fact, they actually started developing condos close to the hotel before they sold out. Without Diamondhead, Pinehurst most likely would have gone the way of the great Catskill resorts of that era or Bedford Springs. They were a bridge from the Tufts era to the Club Corp era. Club Corp even looked at purchasing Pinehurst before Diamondhead but didn’t pull the trigger. It might not have been there for anyone in 1984.

Diamondhead alienated many people when it took over, but from my research it seemed they eliminated the laissez-faire attitude of the employees and expected results and accountability. The locals translated that as not caring about the customer or whatever. I think I translate it as good business practice. The locals here today talk about how Diamondhead ruined Pinehurst even though they weren’t here yet. They don’t make the connection that without Diamondhead, these people are living in Hilton Head.

Now from an architectural standpoint, Diamondhead did do some irreparable damage to Pinehurst. The condos and other residential development have severely hampered the golfing experience on courses 1, 3, and 5. Six is always going to be hampered by residential. The greens on No. 2 are not what Ross intended (although that has not hampered its reputation in the least). Diamondhead wanted to modernize Pinehurst and that was a reflection of what was happening with golf development elsewhere in the seventies. In that regard, they gave the golfer what they considered a more playable golf course. Unfortunately, they eliminated all the character (sandy roughs, pine straw, unkempt edges) and replaced it with green grass (wall to wall rough and irrigation).

Diamondhead did recognize the error of their ways and tried to fix things later. Overall, my attitude toward Diamondhead is that they left Pinehurst in a much better financial state than when they purchased the resort. A misconception is that Diamondhead bankrupted Pinehurst, but that was not true. They used the profits from Pinehurst to fund bad ventures and eventually used the resort to get out of a financial bind with the banks. The banks took over as a debt re-structuring and then sold Pinehurst to Club Corp. It was Club Corp that was able to bring Pinehurst back to the top, but Diamondhead laid the foundation.

What do you think of the most recent renovations to course No. 1?

Unfortunately that work was done after the book was completed and they did the work without a golf course architect. I had the opportunity to ride the golf course during grow-in and witness the final product. The plan was to just re-grass the golf course and make a few adjustments to accommodate a future tunnel between the sixteenth green and seventeenth tees, but it turned into much more, including a bunker renovation.

Although the work was decent, I thought Club Corp missed a great opportunity to distinguish the course with very little extra effort or cost. They should have tried to re-capture the look of the thirties with a little more of the unkempt appearance and more ragged bunkering. It would have been a great opportunity to introduce another product and re-introduce a missing link to the history of Pinehurst.

What are your thoughts on Mid Pines?

Mid Pines may be the most authentic Ross course in the sandhills. The routing is exactly as it was in 1921 and it never has undergone a major renovation. Just a few greens have been rebuilt over the years and minor bunker work. Personally, it is my favorite course in the area (along with Southern Pines Country Club). Unfortunately the course needs a bit of a pick me up, especially the bunkers. Interestingly, Mid Pines is a case study in proper application of accurate restoration of the features. It could be damaging if the Owners utilize No. 2 as a prototype. Although Ross did indeed create grass-faced, flat-sand bunkers in places, it is not his signature style. If that was done at Mid Pines, then every sand bunker would be blind to the golfer and that is not what Ross promoted in his work or his writings. It would be a shame to rely on grass contrast to achieve that look. Mid Pines needs a sensitive hand and on-site involvement.

Tobacco Road “ Why did you include it?

The book is not just limited to the golf courses of Pinehurst. To tell the complete story you must include Tobacco Road for the simple fact that it probably wouldn’t be there if it weren’t for the existence of the sandhills as a resort destination. Tobacco Road is twenty miles away but it is definitely a sandhills course in terms of soil type and its inclusion on the itinerary of most visiting golfers. It is also a bit of a throwback to the Pinehurst courses of old. I think the greens are fantastic because of their wild contours. Luckily the elevation changes on the greens work because the square footage is there to pull it off. The course also has that blur between manicured fairway and native vegetation. That is the characteristic that most describes the Pinehurst courses of the past which was lost with the advent of the ‘Augusta look’ and the focus on controlled playing conditions and defined lines. That was never intended to be part of the game of golf and luckily Tobacco Road embraces that gray area in design and presentation.

What took so long for this book to be completed?

I got busy. In the four years that I spent on this project, we were awarded about six or seven renovation projects, which is just the right number for me to manage without losing the focus on design and ending up in just a management role. This included Raleigh Country Club as well as a few other Ross courses, Highland in Fayetteville, North Carolina, and Pinecrest in Lumberton. Pinecrest actually boasts nine Ross holes and nine Dick Wilson holes, which I believe is the only combination like that in the world. It is such a neat little golf course, but they are limited with funds so the first thing we did was take out about 1,000 trees. As funds become available, we’ll do more.

We also got a trio of projects in Smith Mountain Lake, Virginia: Water’s Edge, Waterfront, and Westlake. All three of these were built in the eighties and have brought about different challenges for me than the golden age stuff we’ve done at Erie (Tillinghast) or Raleigh. We just wrapped up construction at Water’s Edge, which was originally designed by Buddy Loving, Jr. He was a regional Virginia architect from the seventies and eighties so his styling was typical of that era.

Although that is not my preferred design style, it was a fun challenge to replicate the look in an effort to preserve the character of the course and keep the clients happy. For instance, the emphasis was on serpentine lines. The bunkers were actually carved into mounds instead of deriving their shape by working around mounds. By the end of the project, I gained an appreciation for the look and it allowed me to show off some diversity, an important trait to have in the business.

Another large project we are undertaking is Army Navy Country Club (twenty-seven holes in Fairfax and another twenty-seven in Arlington, Virginia). That is another project where diversity and the ability to adapt to different styles really helps. At Arlington, we are creating a more golden age look with bunkers in the style of Mackenzie. This is the first time I have been given the opportunity to get a little radical with my bunkering and it is fun. At Fairfax, we are adopting the Trent Jones style because he originally designed the first eighteen there and we want to create clear distinction in style between it and Arlington for the members. It is a four-year, five-phase project. We just completed the first two phases this past summer.

As busy as I was, I found myself writing this book in many hotel rooms and airports. Plane travel was easy then because I took advantage of the delays to write. I basically wrote this thing an hour at a time. Of course the first edit proved that there were some drawbacks to that process. It was hard to remember what I wrote three weeks ago, but only a chapter before in ‘book time’.

Tell us about your experience publishing your book. Self-publishing usually means black and white, paperback, etc., but this is a lot more.

As I was writing the book, I started researching the publishing aspect of the project and began searching for a publisher. After contacting about four or five publishers, I found that the response was it would be too expensive to produce, it was too narrow of a subject, or they wanted to see a finished manuscript. Because my time was limited, I decided I needed to just finish the manuscript and worry about a publisher later.

At one point, I thought I would have it done for the 2005 Open at Pinehurst, but only got through the first eight chapters. By the time I was completely done with the manuscript (including more research, re-writes, edits, and proofs) it was this past March and I had a choice: Either continue seeking a publisher or do it myself to get it out for the Women’s Open at Pine Needles. I felt that was too good of a platform to introduce the book so I went for it.

Of course, what did I know about publishing at the time? The first step was buying a book called Bookmaking and I read it cover to cover in about six days. I then researched and purchased publishing software. In the meantime, I got proposals for printing which allowed me to specify the book parameters before I started the design process. I chose an American company called Jostens, which cost about 80% more than proposals I got in China and India. I had too much riding on the product, timetable, and my own money to risk anything going wrong, so it really was an easy decision. It was also nice to be able to call the printers throughout the process and share ideas back and forth. Although there was a lot of money involved in the printing, there was not too much difference making the book a full-color hardcover product. I felt the subject deserved that nothing less than that treatment. It was a good decision.

Once I chose my software I spent the next two weeks reading books, doing tutorials, and studying the manuals, which was kind of crazy. I finally sat down the first Saturday morning of April ready to begin. Eight hours later I barely got the margins set and it wasn’t looking good. Luckily that Monday I found a graphic designer who just moved down from New York and had little to do for the next month. His name was Jay Bursky and he knew the software inside out. He and I then took the book from a word document to finished product in 3 ½ weeks. Nineteen hour days with a couple of all-nighters in there as well. We hit our deadline, sent it off on May 7th and a truck with almost seven tons of books pulled into my driveway on June 15th, a week before the Women’s Open began. Now I’m into the promotion end of it and I’ll say it has been a fun experience. I’ll do it again.

How has this experience affected your design approach, if any?

That’s a good question. The research has definitely given me a different perspective on history. Obviously it enabled me to delve into Donald Ross a little more than most people would have without that opportunity, but it was also interesting to see how things evolved from an operational perspective and how even the greatest architects of their time were really subject to their boss’s wishes and a budget. There are numerous instances in the book where the Tufts begged Ross to stop spending money and questioned design decisions in regards to the bottom line. It certainly made Ross more human to me and many of us, especially the GCAer, build these guys up to God-like proportions, which is a mistake.

The whole book documents the development, design, and construction process for a cross-section of golf courses throughout the past one-hundred years, which is just more perspective for me with my own clients and the design process. That was a major goal of the book and it revealed a lot. The perspective in developing The Country Club of North Carolina was very different from developing Mid Pines, The Pit, or Tobacco Road. This is a major element of the book that would certainly appeal to Golf Club Atlas. Just revealing the rough waters many of these courses underwent is important for the average person to gain some perspective.

Now the process of developing this book (aside from the subject) certainly is a parallel to my own profession. The design process is very much the same in both fields. Research (understanding your client or market), writing (design of a golf course), and then production (construction), and promotion (marketing the course) are the same general steps. The writing process, when you break it down, is also very similar to the design process especially when you dissect it: The beginning of each process can sometimes be overwhelming. For example, the vastness of a subject to write about parallels the vastness of a piece of property or the vastness of the confluence of goals and issues a project may have. In both cases, a simple attitude of just moving forward as well as an outline can be very helpful in jump-starting the process. It is just another example of the fact that the creative process still needs some structure and direction. No matter how creative one is, if you can not communicate your ideas, you won’t get to the finish line.

You are a golf course architect. What would it mean to you to tinker with or design for 47 years a la Ross and No. 2?

I am sure every golf architect (or designer of any product) thinks of things they would do differently and to have the opportunity to change things would be great. But at some point tinkering can be counter-productive as many of the better ideas are truly your first ideas. I am a very instinctual designer, especially when trying to replicate natural landforms in golf course features and instinct will usually produce the best product first, even after consideration of numerous alternatives.

Now the opportunity to tinker also allows for some great experimentation and that can’t be bad as an architect. Again, there are many things that we as Architects want to try but have no idea whether these concepts have validity. Often times, due to budgets, timetables, and just simple reality, we are forced to maybe choose the safer option. Tinkering over time can open up more choices and that would be fantastic.

When you first ask this question, my instinct is ‘Does that mean that after 47 years, your masterpiece should be perfect?’ I don’t think that if Ross had seventy years to tinker he would ever say it was finally done. Designers are never finished and if it wasn’t for deadlines and the reality of making a living, some would never finish. Of course the Pinehurst No. 2 that we see today is much more revered than the No. 2 when Ross passed on. It was also very much different. Personally, I lean toward the No. 2 of Ross’s day more so than the ‘finished’ product of today but the point is that a golf course evolves long after the original design process ends (for good or bad, it doesn’t matter). That is why pure restoration will never truly work. Although restoration is more of a technical process, the creative element is necessary to adjust for today’s conditions.

But yeah, I would love to tinker on my own No. 2 for the rest of my life. It would be a lab of experiments with no ramifications and I could take those ideas elsewhere. I am sure Ross did the same. Really, he used all of Pinehurst to develop his style and learn on the job.

Can we gain yourpermissionto re-print your epilogue here? I thought it was particularly well done.

YES. Here it is:

Epilogue: The Future Of The Sandhills

Pinehurst has often been nicknamed the St. Andrews of America. Although there is a strong fraternal relationship between Pinehurst Resort and the St. Andrews Links Trust, that connection stops with the actual golf courses. Layouts in St. Andrews and the North Carolina sandhills are carved out of sandy soils yet the sand golf features characteristic of Scotland are seldom replicated in the sandhills. Instead of a links strategy and rough conditions, the American ideal of perfectly controlled golf conditioning dominates the sandhills.

Unfortunately, most current golf course design and management trends in the United States are based on controlling the golfer’s playing environment. Each golf hole has perfectly manicured landing areas, fully in view from the tee and waiting to catch everything like an oversized first baseman’s glove. Putting greens have emerald-colored putting surfaces and always stand at attention to the golfer with a welcoming back to front slope. The bounce and roll which helped make golf such a gift in the first place are some of the qualities missing on many of the sandhills area golf courses today. The elements of randomness and mystery have been effectively removed from the game in the process.

For me as a golf course architect, great golf is all about creativity and inventiveness in shotmaking, two golfing traits which have become non-essential in today’s golf design. The future sandhills golf course should be dominated by the one site characteristic that truly separates great golf courses from all the rest: SAND. Sandy soil is the defining mechanism of the sandhills area and is the best medium for creativity and inventiveness in golf course design. Yet many golf course designers ignore the freedom sandy conditions provide in golf course design. The future of Pinehurst is a golf course that maximizes the playing characteristics of sandy soils with golf course features that are reflective of conditions found in the links courses of the past.

The compact, spongy underlayment of thatch and native grasses on firm, sandy ground gives links golf its flavor. Undulation, in the form of ridges, ripples, rills, hollows, and knolls, is the primary defense found on a links course. Links contours deflect one’s ball from a desired path and at the same time may direct that same ball into bunkers and hollows. Links play promotes the art of shotmaking (adjustment of the golf swing to adapt to various conditions). A golf course that promotes shotmaking presents challenge to the golfer through deflection and re-direction of the golf ball. Adept golfers observe the way the ball travels along the rolling landscape, knowing the ability to control the bounce of the ball is the key to success. With few vertical elements to rely upon, the golfer must rely on judgement, feel, and memory. It is these skills which distinguish links golf from the modern American game (played through the air) and is what first made the game so attractive. Today’s golf should be played in similar links conditions in keeping with the origins of the game.

Sandy Pinehurst soils allow the golf course architect to use undulation to create strategic challenges for those golfers seeking out a birdie, yet still allow the lesser-skilled an opportunity to enjoy the game. The incorporation of undulating ground will result in specific targets to gain a considerable advantage. For example, natural ridges can provide landing points for bold tee shots, a stiff downslope shall give the golfer hope of gaining extra yardage, and out of a natural rise a sandy hazard can emerge to entice the golfer with an alternate (yet riskier) route. Features can be plateau fairway areas that provide better angles or views to the next target or specific quadrants of a putting surface for the aggressive player looking for a short birdie putt. Yet because undulation is truly a hazard which promotes challenge and does not unduly penalize, the disadvantaged can play at a fair pace without fighting their own physical limitations. As baby boomers get older, they will appreciate the ground game. The days when they may have once welcomed a carry over water seem less and less appealing.

With the ability to develop the rolling sand dunes of Pinehurst into dramatic links-type features, the golf course architect can correctly develop authentic rolling golf course features that more resemble the waves created by thousands of years of erosion found throughout the British Isles. Many architects fail to accurately replicate natural land forms to use as hollows and mounds. Often times it is a result of poor soil conditions, but more often than not it is the inability to recognize the merits of nature and translate them to the ground. The deficiency in mounds and hollows do not come in the high or low points which most people first recognize. It is in the inability to create broad waves between two high points or two low points. The resulting products are choppy, out of scale chocolate drops or pots.

The future of golf in the sandhills is in creating a golf course that takes full advantage of sand’s ability to sustain low-profile, well-draining golf course features and hazards full of variety and strategy. Sand bunkers can appear simply as extensions out of the ground. They should mimic nature unlike artificial hazards that must be built on top of heavier soils. Sand soils also afford the opportunity to move away from the perfectly manicured fairways and re-introduce the rub of the green “ sandy rough areas which bleed out of the pines and creep into the fairway.

By making a conscious effort to develop strategy on a hole by hole basis, the golf course architect can develop enough options to provide a myriad of choices for the golfer. Of course, choices on any soil can only become reality through proper fairway width. Enough of it will blur the black and white choices that render many holes boring after only one or two rounds. Instead, a wide fairway provides enough alternatives that the golfer must ponder a gray area of choices. It is this variety in strategic choice that will create memorable experiences and repeat play.

The practicality of width can provide broad golf course corridors which, in turn, can provide an expansive backyard for the homeowner who may choose to live along this golf course. Moving away from the age-old trend of double-loaded fairways and maximizing home sites, the future of Pinehurst will lay in the creation of premium lots of sufficient acreage. Minimizing the density of homes will create a sense of open space between adjacent homes and across the broad fairways of the golf course. The result will be a more private and natural setting for the homeowner.

A sandhills throwback to the golf courses from one hundred years ago will show a new generation of golfers that the simple thrill of hitting a golf ball over, through, and around nature’s wonders is much more entertaining than a perfect lie within a painted picture. A memorable round will result from the architect’s ability to provide strategic options from hole to hole. In turn, these options will allow the golfer to make choices “ some correct and some not so correct. Undoubtedly, the golfer will yearn for the prospect of another chance to make the right choice and the golf course developer will reap the benefits of repeat play. The future Pinehurst golf course will not only possess these essential ingredients of great sandy golf, but also be more sensitive to the ground, more environmentally-friendly, and most importantly, affordable to construct and PLAY.

How does one purchase ‘Pinehurst~ Home of American Golf’?

By contacting me through my web site www.golf-architecture.comor by phone at 910-255-3111. The price of the book is $65.00 and shipping is an extra $5.00. Please know that 10% of the book proceeds (for the life of the book) go to the Tufts Archives.

The End