Feature Interview with Ian Andrew

December, 2008

1. How did you get into golf course architecture?

I used to watch the Bing Crosby Pro Am with my father. I would watch the tournament and draw out all the holes “ I was pretty infatuated with the course. Eventually I not only drew the holes but converted it into a board game based upon an old English Golf game we had called Par Golf.

A photograph of the Par Golf board game; note how a version of the Road Hole is its eighteenth.

My father still remembers that one day while watching I asked, “Is it somebody’s job to design golf courses?” Of course he responded. And I said, “OK that’s what I’m going to do.” He remembers that day distinctly because I was only 13.

My Dad assumed this would be a flight of fancy but encouraged me and bought me the World Atlas of Golf, my first book on golf architecture. He taught me the game, which I became quickly obsessed with, but was more surprised that I remained more obsessed with golf architecture. So he bought me more golf architecture books and eventually managed to find me a photocopied version of Golf Course Construction in America that I was begging for. He also began planning family holidays around golf (my Mom is still angry about this even today). The first trip we ever took was to Highlands Links when I was 16. Other trips would eventually included Pinehurst, Monterey, Scotland and England.

I ended up calling the ASGCA for advice and someone there recommend that I take Landscape Architecture. I did, and while I was interning with an LA firm, I was put in contact with Doug Carrick. We kept in regular contact for about two years before a position opened up and I joined him.

2. You began with Doug Carrick twenty years ago – tell us about it.

I was very fortunate to apprentice with Doug. There was no question when I joined Doug that he was the rising star in Canadian golf and the nicest of all the golf architects I had met. Doug took me in, taught me about architecture, invited my opinion and slowly gave me a chance to learn through a series of new projects where I assisted him. I loved what he was designing and soaked in everything he had to share “ it was a glorious time.

As the firm grew, we found that the workload rapidly expanding. Renovation work had begun to become a major source of business as the established private courses felt the competition from so many new courses, and I began to get involved in that side of the business. I continued to assist him with new course construction but over time that role diminished as the renovation began to roll into the office. Eventually I ended working almost exclusively on renovation work while Doug handled most of the new work. These were roles we were both happy with. As we got busier, I gained more autonomy, and I enjoyed that.

3. So why did you decide to leave?

A close friend of my wife and I died of Cancer at a very young age and it shook my foundation. My wife and I talked about not wasting opportunities now and taking more chances. I ended up with the mantra of “no regrets.”

Over a period of 10 years I watched Doug becoming more and more interested in what he could do with manipulating a site. During the same period I had gone to see a lot of courses in the States and the UK, including a little known course called High Pointe that I really liked. The net result of my travels was I began to openly question why we were moving any dirt when I felt we didn’t have to. While Doug and I had started on the same page we had grown in completely different directions and it made it more complicated to work on projects together.

Spurred on by my friend Chris Brands (who was also the person who introduced me to this site) and my new mantra I ventured out to the first Archipalozza. Archipalozza was a meeting of the next generation of architects organized by Tom Doak. It turned out to be the best kick in the ass I ever got and a key moment for me. I was quite taken by the friendliness of all involved and how they openly shared what they knew about architecture. The other major impact was seeing Pacific Dunes. I was blown away by the course, the way it sat on the land, the ground game opportunities, the width of fairways to deal with wind, the interior bunkering and the green contours. This was the type of course that I wanted to build. I left Archipalozza wanting to build courses completely differently than were being done where I worked. I now knew that I was going to have to leave “ so now the question was when.

The decision to go came after restoration of St. George’s Golf & Country Club. I was asked to research and then restore some of Stanley Thompson’s greatest bunkers. I had done other restoration work at other clubs and was finding that more clubs were seeking me out to perform restorative based work at their clubs, but this was the big one. I felt an enormous amount of pressure to produce an accurate restoration because at that time I felt St. George’s was Stanley Thompson’s architectural masterpiece and I couldn’t bear the thought of making even a single mistake. So I put in extra effort in the research to ensure accuracy despite some people’s objections to the value of a restoration “ it was contentious to some. The superintendent John Gall and I worked on coming up with techniques to deliver the original feel of the bunkering which eventually became the need to build everything by hand. I learnt a lot about the value of detail work and from that day forward obsessed about exactly how things were going to be built and began to demand techniques that produced superior work.

At the end of the project, I knew I was ready to leave. So I asked myself the one question that you have to ask yourself before you cut ties. Would I be more upset if I went out on my own, failed, and found myself out of the golf design business? Or would I be more upset with myself if I didn’t try.

No regrets “ I was ready to go.

My wife and I sat down and talked about how we’d do this, since a move like this affects the entire family. She was more comfortable with the move than I was but stunned me by recommending that I don’t go right away. She said that I should take a year and make sure you leave on the very best of terms. I had so much fun in the early years with Doug, but as we got busier and spent less time working together, we both had grown apart. It stemmed from having different views on design and eventually about how to run a business. So for simplicity’s sake we generally worked independent of each other. So I approached Doug and asked if we could work on new courses together like the old days. It took far more time than I anticipated and ended up delaying my exit by an additional three years (which I do not regret), but I had a lot of fun working with Doug on Muskoka Bay and Frog’s Breath.

I think he was stunned when I left because it was the best we had worked together in years, but he also understood that there was a time to go and was supportive.

4. What advice would you give to associate architects looking to go out on their own?

- Hit the ground running. You want to be the one to break the news to everyone. Have a list of who you should call from media through to potential clients. You need to make all those calls in the first couple of days.

- Have a web site up the first day. It gives your current clients easy access to information about the new business. In my case this turned out to be crucial to few particular boards that would have a decision to make. It became even more important when I began to direct all future clients and media inquiries to the web site for information.

- Have a media strategy. I called each member of the media personally and had lunch with anyone who would meet me. It got a real boost when at one lunch Robert Thompson recommended that I should blog about my business and about golf architecture. He felt that I had to educate people about what I wanted to do differently from other architects so that I could separate myself from rest.

- Have a network in place. Once I left I received a series of calls from friends who wanted to wish me luck and a couple suggested I call certain clubs because they were looking for a new architect. Work can come from anyone from owners, to superintendents, to construction people. My networks lead me to five new jobs in the first year.

- Have a list of projects or clubs that you are going to actively chase. Getting new work right away has an impact on how you are perceived by other potential clients and the golf media. Nothing beats a press release to announce you have new work.

- Understand the business end of running a business. I can’t stress this enough. Incorporation, liability accounting, etc. You will spend far more time than you can possibly imagine learning how to run a business and then administering it on a weekly basis.

5. You mentioned Robert’s suggestion for having a log – did it work?

One of the things that I needed to do after leaving Doug was make clear the differences between myself and all the other architects. I was pretty confident that I have something different to offer in Canada, but my problem was how to get that message across to potential clients.

When Robert recommended using a blog, I had some initial doubts, but I was willing to give it a try since it would cost me nothing but time. So I let friends, clients and the members of the media know that I was going to commit to writing every day for a year. I managed not only to write a piece a day, but to extend the blog for around two and a half years. At times it felt like a burden, but without that commitment I was not going to develop anyone’s interest in what I was doing. I had no idea that it would eventually escalate to 6,500 individual visits a month before I finally pulled the plug.

What was not planned was how the blog affected me as a designer. I had spent most of my life reading about architecture and going to see other courses. But the process of breaking them down and explaining them to an audience became surprisingly educational since often found myself exploring more deeply into the subject matter. I also ended up reading a couple of new books and articles that profoundly affected what I thought about design. I became keenly interested with how a course should play and the players should feel throughout a round.

The other big change in philosophy came from writing a series called The Future of Golf Course Architecture. It made me take a more serious look at the idea of Environmental Design. I discovered I could reduce the impact a golf course has on the environment without having to compromise my approach to golf architecture. The most fascinating part is the courses are actually cheaper to build and cheaper to run “ so the question begs why wouldn’t you take on that approach.I think if you read the blog from start to finish, you can see my transition from someone full of ideas, to someone who has a clear idea on what they want to accomplish. For me, the blog contains a treasure chest of ideas and techniques that I can draw on to deal with a vast array of different situations and circumstance. There is no question in my mind that writing the blog made me a much better designer.

Ian on his blog!

6. You have recently been hired to restore Highlands Links on Cape Breton island. What are your goals there?

The biggest problem facing Highlands Links is the falling perceptions of the course. The common reaction of visiting players last year was that while the golf course is wonderful, the conditioning was unacceptable. Potential visitors were beginning to question whether it’s worth the trip.

The priority is ensuring the course is always in better condition. So I recommended that they begin to cut down the trees last fall and deal with the main source of their agronomic problems. Clifford (the superintendent) and I went over what needed to come down and he removed as much as he could last fall. The Park also understands the problem and stepped in with three additional weeks of hours to keep the clearing going. This must remain a focus until all the green sites are in good growing environments.

The community relies on people coming to play the course so improving conditioning will ensure that people continue to make the trip. People will really notice the difference by the fall.

I would love to say that the restoration will be the next stage, but the reality is that there is barely any drainage on the course. There are areas that don’t drain, other that are inundated by mountain run-off, and the problem of the Clyburn Brook which easily overflows its banks on a regular basis. The course needs to have a proper drainage network that efficiently removes the excess water from the course after a major storm.

While I know this may delay fixing the bunkers or paths, this all has to be done too.

7. What three design features would you most like to see restored at Highlands Links?

I’m sure most of you would think that restoring the bunkers would be my first choice but it’s not. The thing I want to see most is the return of the ocean views. I see most of this happening right away! Stanley was well known for his use of borrowed scenery and Highlands Links was no exception. He routed and planned holes for their views of the ocean, the Clyburn estuary, and the mountains around Clyburn Brook. The plan is to open up all the corridors and return the vistas that were originally found in the old photos.

Look at the view opened up down the right of the fifth at Highlands Links if the trees could be removed! In addition, the wind would play a bigger role in how this par three plays, always a good thing.

The second thing I would like to do is restore the bunkers. Highlands is in pretty much the same situation that St. George’s was when I was asked to restore the bunkers. Most have been altered, some relocated or filled in, but most of the mound complexes are still intact. We have some pretty good documentation and should be able to put the course back the way it was. In particular, I’m looking forward to restoring the whimsy. For example the 6th hole was called Muckle Mouth MeG and featured the woman’s face with an unusually large mouth when viewed from overhead. The other is the 13th called Laird which featured the toothless smile of the original landowner done in bunkers on the left of the green.

My third wish is to reorganize the new cart path system. They have added a continuous path system that includes paths that crossing fairways and paths beside greens. Fortunately they are all gravel and can be easily changed. The paths need to be reduced down to what is necessary and then have those hidden from play.

8. What were the biggest surprises you found during your research?

I had no idea that there was a line of sand dunes in play off the tee on the 4th hole. From the right side you had to carry a line of them in order to reach the fairway. I dearly want to restore this feature and return the reason for the name of the golf course.

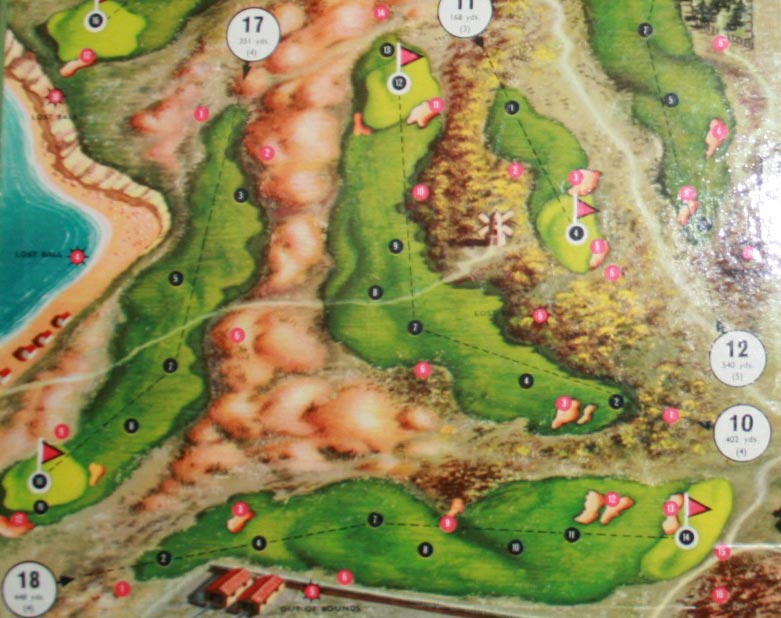

An aerial view of the fourth at Cape Breton shows how Andrew would remove trees down the right and bring back the dune bunkering between the tee and fairway.

You always expect some of the greens to have changed through mowing and maintenance, but the amount of change on two of them surprised me. The green on the 11th is 30 feet short of the original position. It turns out around 10 years ago they lost the back of the green, so they cut down the approach as a temporary green. The area received sun and the green performed se well that they left the green in its new position. The 12th green was originally 30 feet larger in front making the green approximately 10,000 sq.ft. Considering the hole was 245 yards in 1938 and in a tough growing environment that would have made perfect sense.

9. What other interesting things you have found while researching Stanley Thompson?

Geoff Cornish had a set of the plans for Capilano with him when he travelled East to join the war. He placed them with his other valuables in a storage locker which was empty when he returned home. The only other set were lost in a fire at the maintenance facility.

Through conversations with Geoff Cornish I found out that Thompson produced most of the plans (that have bunkering) after the work was finished. Some plans like Westmount turned out to be his own recommended renovation plan for the course.

I found and bought a complete collection of Jasper photos for the opening. These showed the state of the course before he was brought back to renovate it after completing Banff Springs. While the scale is the same, the bunkers are far less complicated in shape and character.

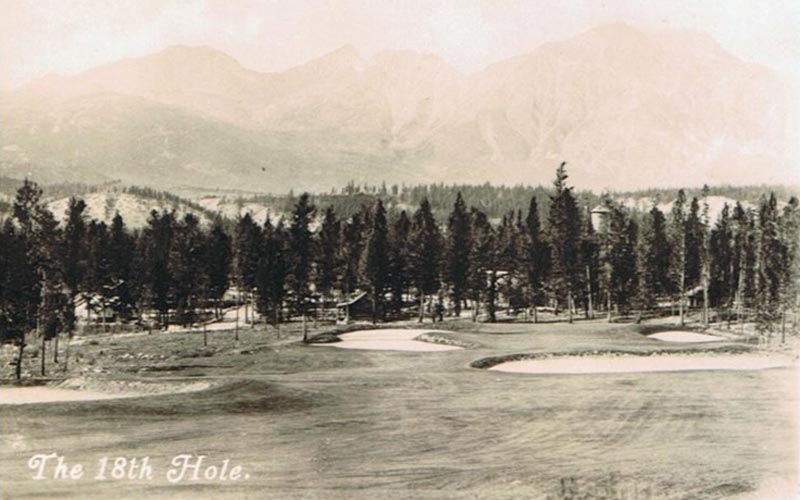

The all-world finishing hole at Jasper Park has always enjoyed many admirers, including Alister MacKenzie.

10. What interesting information have you uncovered while researching other architects or courses?

Scarboro Golf & Country Club originally hired Willie Park over Stanley Thompson. When Willie went home because he was quite ill, they gave the job to the A.W. Tillinghast on the recommendation of the USGA. This left Thompson angry with Tillinghast for the rest of his life and according to Geoff Cornish. He was the only architect that Thompson did not like. In 1935 Scarboro finally hired Stanley “ but only to be their agronomist!

My most memorable moment was a walk around at Penn Hills, in Pennsylvannia. I was researching Walter Travis in preparation for Lookout Point. I innocently asked my host if they had ever seen any drawings for the golf course – and he said they knew of none. An employee from the maintenance staff happened to be in getting lunch and suggested we look in a particular locker since there was roll of drawings in it “ just in case. We went down to open the locker which was full or trash and boots and a used oil container. There was the role of drawings, which turned out to be prints of the clubhouse. We unrolled them all because they were incredibly interesting (it was the original clubhouse design for The Park Club in Buffalo but was designed too small). We unrolled all sorts of small plans till finally we came to the centre and found a roll of linens. These featured golf holes and turned out to be Travis’ working drawings – not just for the nine holes he built, but also plans for the other nine that was eventually built (albeit differently) by Dick Wilson.

11. Tell us about Walter Travis the designer. What are some facts that we may not appreciate?

When I became involved with Lookout Point, I set out on a journey to understand the architecture of Walter Travis. I visited a dozen courses which helped prepare me for working with Lookout Point. Many left me with questions about the differences, but I didn’t worry too much about that because I had good research on Lookout Point.

It all changed when a couple decided to hire me and there was a lot less historical information. I ended up calling Bruce Hepner to find out what he knew about Travis’s architecture and to ask his opinions on a number of matters (which included a great discussion on what constitutes a restoration). He had run into similar situations and though of Travis as a bit of an enigma, but really liked his work.

To answer the question is tough, but what I can do is point out some of the unique features at a few clubs that would help you learn about Travis.

- Hollywood (1917) was actually a renovation, but that hardly matters. The course was clearly inspired by Pine Valley and featured massive geometric expanses of sand and some incredible carry angles. I have not seen another course with near the same acreage that Hollywood had. I have yet to see any of his other work that matches this.

- Onondaga (1918) features nine blind tee shots up over large ridges to fairways above and beyond. One of the par fives asks you to hit blindly over the next ridge too. Blindness of both landing areas and green sites is more common on a Travis course than any other architect I have seen. Onondaga is the course that pushes it to the extreme “ yet surprisingly it works – because of the space between tree lines and elegant green sites at the end of each hole.

- Lookout Point (1921) features massive fescue-topped mounds and mounding complexes that were used to separate all the open areas. Most of the complexes are still intact and few courses can touch this one for the boldness of its mounding.

- Yahnandasis (1922) feels like it was draped over the land rather than built. It’s certainly one of my favourite routings for the way it uses the undulations in landings, and also how it often defies convention with green placement. It features a couple of sunken green sites and two full punchbowl greens that are truly outstanding.

- Country Club of Scranton (1925) features 15 of the most mind-blowing greens I have seen. The compartmentalization of pin positions is stunning. It’s largely done through interior contours with many coming near the middle of greens. But Travis also used a combination of long rolls, reverse tiers, sunken pockets and tiny plateaus to make each pin position complicated. Throw in the use of short grass beyond the greens, the use of mounding and his insistence on a bounced in approach and you get some entertaining golf because of those greens.

Nobody built greens like Travis – just look at the amazing interior contours found within the eighteenth green at Country Club of Scranton.

12. You have been working on Country Club of Scranton since 2003. What is the current status?

We’re so close to getting things back to where they should be. Over the years we have restored all the greens to their original sizes and recaptured all the lost pin positions. At the same time we have returned the short grass around the greens and removed a couple of the bunkers that cut off a running approach. We’ve widened out all the fairways to their original width which brought bunkers back into play and others to the interior of fairways. I guess the biggest change has been restoring the views. The course had begun to look decidedly parkland, which worked against the intent of the routing since it was done to take advantage of the views to the surrounding mountains. The trees came down and the long native grass was allowed to return which added a wonderful contrast of colour and texture to the course. Like all courses returning the long grass, we are still in the process of balancing out beauty and playability.

The big jobs remaining are the bunkers and the drainage network. The goal for the bunkering is to return the feel and character of the original bunkers. One of the key elements to me is the return of the fairway mounding complexes. The old aerial offers an incredible window into the character and Travis plan is a great asset too. The greens need drainage since they do have pockets, so do the bunkers, areas that seep throughout the property and a couple of major collectors need to be built to be more efficient with the water that is collected.

13. Do you have a favourite hole at CC of Scranton?

My favourite hole is the 7th. The hole is a long four that was clearly designed with a running approach in mind. The hole plays to a left to right canted fairway that turns around a massive oak that’s way too big to carry from the tee. The fairway then runs aggressively downhill and right into the green that slopes backwards at the start. The kicker is the green site. Not only does it have a double roll in the middle, but it’s a built up peninsula. The land falls away to left, very steeply on the right and of the face of the earth in behind. 25. Since there were no original bunkers and the short grass came up to the banks on both sides “ missing wide or long was a complete disaster.

Though the bunkering isn’t original, the green and its amazing rolls are vintage Travis.

14. Name a favorite hole (that you had nothing to do with) and what you like so much about its design.

I’ll have to say the 6th at The Creek Club by Seth Raynor would be a favourite.

The tee shot appears fairly simple because there is tons of room out on the right and the bunker barely comes into play. The problem with that play is from that angle you’re pretty much dead. You really need to be on the left to have a reasonable chance at approaching the green. The forest on the left of the hole defends the ideal line and a shot into the forest is a lost shot. Ideally you must hit a light draw around the tree line to gain position on the flatter plateau for the approach.

The approach is a stunner. The green is a reverse redan punchbowl!!! This is the most unique and wonderful green complex I know. The shot is a fade into the throat in front of the green to access the front half of the green, or at the front left to access the back pin positions. The ball will release and run a long way from both spots. The joy of the hole is that it uses the rambling hillside to define the locations of the landing area and then a perfect natural ridge to find the green site. Since the hole goes with the grade the whole way everything blends in magnificently.

As seen from behind, the sixth at The Creek falls steeply downhill before reaching its one-of-a-kind manufactured punchbowl green.

15. Would you have the guts to build a similar hole/green?

I would like to say yes, but that wouldn’t be true.

I would hope that I would have also seen the basic routing of the hole. I tend to go with the flow so I may have even built a green that falls with the land, but I never would have manipulated that green site to come up with his punchbowl concept. The green site takes this hole to another level.

I think we would all like to believe that we could do something this bold or push the limits of architecture, but in reality very few ever get outside the box. That’s not saying those architects are not clever, because they are and most of the great courses in the world don’t get outside the box either. But it’s the holes that do that leave us with our mouth wide open in shear awe of what they have accomplished. The other side of this is that most attempts are a dismal failure and that’s why we see so few attempts to try ideas as bold as this green.

16. Name a routing that You admire and why.

I’m not alone in admiring Merion most of all. Many have pointed out the small acreage or the fact all eighteen holes are capable of standing on their own “ but for me it’s the flow. Merion is a wonderful three act play. You open with a series of tough and testing holes, then shift into a run of shorter holes all full of opportunity, and then try surviving a grueling final stretch that is as tough as any in golf.

I like the way that flow manipulates the player’s emotions. The opening six is all about managing expectations and trying not to give any strokes away. The holes are plenty tough in spots but the two par fives gives you a chance to come through the opening stretch in good shape. The seventh through thirteenth is all about opportunity. You have a series of holes where the player can play aggressively and make a few birdies. The final stretch is all about survival and trying to limit the amount of strokes you give back.

It’s the middle stretch that gives Merion its unique flow. The average player loves it because it’s a temporary reprieve where with reasonable play they can make a couple of pars. The good player finds this still to be a pressure filled section since they know they must make a few birdies “ the pressure comes from knowing that the final stretch of holes is still to come. They often become too aggressive giving up unnecessary strokes because while short they are no less dangerous.

17. Money is tight now and the expense of the sport has driven players away. What can you as a golf course architect do to minimize costs and/or help get the game back on solid footing?

When I look at most of the historical courses that I work with, I can clearly see that earthworks were generally limited to tees, greens and bunkers. Therein lies the lesson of the past. This would remove the need to strip and replacing topsoil, grade fairways and roughs. Leaving the areas beyond golf untouched would limit disturbance of the site, seeding required and the scope of grown in. This is all common sense.

What we need to do is be a little more restraint in its approach. Concentrate more time on building better green complexes, use less bunkers and place them in more effective locations. Lose the target bunkers, and adopt bunker styles with less intensive maintenance. Even building fewer tees and making them larger would help. The biggest one would be build shorter courses that meet the need rather than the ego.

If you add in reductions in maintenance expectations, less maintained land, minimizing clubhouse facilities, walking only courses, it’s real easy to find an effective business model that can help keep costs and green fees down.

18. Earlier you mentioned Bruce Hepner earlier. How do you deal with competing with other architects particularly when you know and like many of them?

There is a series of architects whom I deeply respect. I’ve had a beer (or four) with most of them and talked to the others on the phone. These guys are important to me since they are willing to share what they know, offer advice when needed, or be supportive when things are not going as well as they could.

So when I’m up against someone I respect – I feel honored to be included on a list with their name on it, My philosophy will always remain the same – if it’s not going to be me “ I’m glad if the work is going to someone who will do a good job. I think if you ask all of us, we’ll answer the same thing, we don’t mind missing out on a project as long as it goes to someone who cares.

The first job I ever chased on my own was Taconic. I got down to the final two, and when they told me that they had selected Gil, I told them they made a great choice. I was disappointed because the course was really cool and that it would have been a great start for me “ but I thought that they had made an excellent choice and Gil will do great work. It was easy to move on right away.

The only time I get upset is when I lose out on a historically important club where the other architect has no knowledge or interest in the club’s history.

19. Have you ever worked with any of those other architects in collaboration?

Scarboro Golf & Country Club was a collaboration between Gil Hanse and myself. I think the pairing worked great. I was able to spend a great deal of time researching the property and Gil brought his wealth of experience working on A.W. Tillinghast courses.

One of the findings of my research was that Tillinghast’s renovation left Scarboro with no fairway bunkers. By digging into the minutes and the financial records, it became clear that the reason was not architectural choice but because of the financial hardship the club was going through at the time. When I found the 1934 Irrigation Plan, it was quite clear that it was drawn over Tillinghast’s concept plan – and it had fairway bunkers.

When we began with Scarboro, there were 17 fairway bunkers, all modern in appearance and placed parallel to fairways. Gil and I spent a series of days walking the site, going over the historical information and talking about the holes where it would require our input on the bunkering. We worked through all the possibilities and simply chose the idea or solution that we both thought worked best “ no arguments or disagreement “ it was really easy.

For the most part, the work has its roots in the research. That meant 13 of the bunkers were removed and the remaining four were brought in towards the fairway to create strategy and to help create the fairway twists that Tillinghast wrote about. Gil and I added in another 6 bunkers to the course, mainly in the second landing areas on the par fives, to help twist the fairways and make players to think about the second shot. The most fun of all the features is the grass Sahara in the second landing of the opening hole. When combined with the relocated bunkers on the first landing, it took a straight and long five and gave a remarkable serpentine shape.

I enjoyed my time with Gil and I found him very easy to work with. I think when two architects respect each others opinion; the extra set of ideas can help the two of them push the craft a little bit further. I would certainly like to do this again and there at least a half dozen people I would do this with in a heartbeat.

20. You also began work with your first Ross this year, how did that come about?

Last year I was asked to submit a proposal for Plymouth Country Club. I was surprised to be invited, but was recommended as an interesting alternative to the usual suspects. I knew the first question would be about my lack of experience with a Ross course, so I took that on directly in my proposal. In short my point was that I had a broad set of restoration experiences and that my belief was an accurate restoration came through research. I talked about the importance of treating each Ross course as an individual and that as long as a person was committed to doing the research and knew how to build using similar techniques that they could work on various architects.

I got an interview, and after seeing the course told them exactly what I would do if given the chance. I felt I had nothing to lose so I was very direct. Actually I’m always very direct come to think of it. We talked for around three hours about Ross, architecture, restoration and Plymouth and I think my enthusiasm was what made them willing to give me a chance.

I knew this was the perfect opportunity for me. So much was intact and there was so little that needed to be changed but it needed a lot of attention paid to getting the grass lines in the right place. I’m really going to enjoy working with Plymouth, I like the people and I really love what Ross built for them.

Plymouth Country Club is one of the real hidden gems of New England golf.

21. Weir Golf Design announced in January, 2009 that they selected you to become their partner. Congratulations (!) but does that mean your giving up your renovation business?

No, if that was a condition, I could not have accepted the opportunity. How could you possibly walk away from the people who came with you when you started out on your own? But that’s a moot point since the all the people involved in the selection process saw my renovation business as an asset rather than an issue.

22. How will you handle the new work load with Weir?

Our plan is for Weir Golf Design to restrict ourselves to one or two projects. Mike’s a huge fan of the work of Coore and Crenshaw and both of us see there business model as the best one for us. Neither of us have any interest in anything but a small operation focused on quality rather than quantity. In the future I can see one other full-time person to help deal with the renovation side and assist with new projects. My long term goal is a yearly intern position with an emphasis on them gaining experience. I think what Tom Doak is doing is wonderful.

23. What sort of ideas does Mike bring?

I’ve spent quite a bit of time getting to know Mike better and to get an understanding of his architectural ideas. He’s had a lot of time to think about this since he’s entertained the idea for quite a few years before deciding he was ready to commit the time involved. He’s even visited places like Sand Hills.

I’ve enjoyed the fact that he can break down what makes the 10th hole at Riviera great. He’s also willing to share opinions on holes and courses that he doesn’t want to emulate too. I’m most impressed with Mike’s focus on the smallest of details like the stance on the approach or the implications of a particular roll in the green and how that impacts his approach to the hole. He’s certainly a thinker in his approach to playing a course and this approach has helped make him keenly aware of the impact of certain design decisions. A great example of this is his love of long slow doglegs found at courses like Colonial “ where you have to work a little if you want to attack the holes. He would like to see us use that approach when we get the opportunity.

Interestingly Mike’s ideas tend to focus on the average player’s ability to enjoy the game. In general, he wants us to build shorter courses with more variance in the yardages and more options available through our architecture. He sees width as being an important part of playability and for creating choices from the tee. He’s interested in pursuing ideas like central hazards and interior bunkering that keep width and still challenge better players. Mike’s a huge fan of drivable fours and short par fours, and sees the potential for a couple on each course. He loves links golf and would like to see more short grass around greens and a bigger emphasis on chipping on his courses.

This rendering is from one of Weir Golf Design’s potential sites for a new course. Note how the player would use the left to right sloping fairway to seek the best angle into the green.

24. What should we expect a Weir Golf Design to look and play like?

You’ll find:

- Lots of width

- The freedom to take on as little or as much risk as you like

- The opportunity to flirt with trouble to gain advantage

- Open fronted greens to allow creative approaches

- A tremendous amount of ground game options around them

- Less disturbance of the site

- The incorporation of native grasses into the bunker complexes

- Firm, fast playing conditions with very little rough

The End