Feature Interview with George Thomas

September 2001

For many people, strategy lies at the heart of a golf course. Without it, a course has no enduring quality and eventually a golfer will grow weary of playing it. And for many, the architect who best imbued golf holes with strategy was The Captain, George Thomas. Geoff Shackelford recently caught up with Thomas at a rose show and below is the Feature Interview that Shackelford was able to conduct.

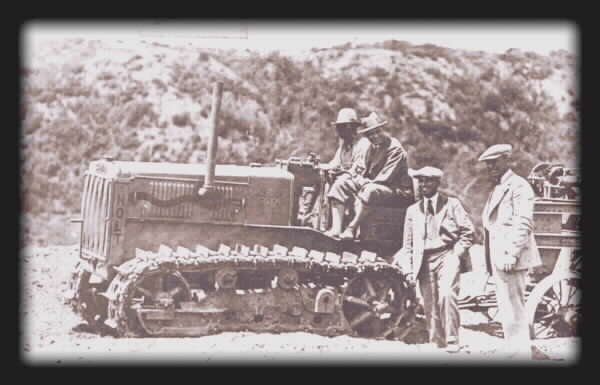

Thomas and Bell

1. What impact did the Philadelphia School of Design have on your design philosophy?

Philadelphia School? I’m not sure what you mean. There was no school of course design in my day. Though I did have many fine classrooms to study. On the green committee of the Philadelphia Cricket Club I aided in the work on their reconstructed course, and in the building of their new Flourtown course, the first being done under the supervision of Donald Ross, the second from the designs of A.W. Tillinghast, both golf architects of the highest class. Before this, and as a member of the Sunnybrook Committee in Pennsylvania, I was connected in its construction with Sam Heebner, Joe Clark and Donald Ross. I always considered Hugh Wilson of Merion, Pennsylvania, as one of the best of our architects, professional or amateur. He taught me many things at Merion and the Philadlephia Municipal; and when I was building my first California courses, he kindly advised me by letter when I wrote him concerning them. He also was a loyal friend and a fine golfer.

2. You maintained your membership at Pine Valley even after you moved to California. What impressed you the most during your time at Pine Valley? Did you ever return after moving to California?

I was a member of Pine Valley at the time of its construction and I watched George Crump build it. I grew up with it in golfing knowledge. Pine Valley is for superlative play. It demands length and accuracy off the tee, and a fine field of shots for perfect golf. Its hazards penalize severely, and its strategy compels finesse. To my mind Pine Valley is the acme of golf in this country and any club which expects to build a fine test of golf should, if possible, have members of its committee carefully inspect this wonder. I did return there in 1928 I believe. Flew cross country if you can believe it. Bill Flynn, a wonderful architect and friend, asked for my support during his effort to make some modifications to the course, namely the alternate ninth green. As a member I could not turn he or my fellow members down, and it was wonderful to return to George Crump’s masterpiece. How we all loved George Crump who made this dream possible and how we all sorrowed when he left us!

Artist Mike Miller's interpretation of how the 3rd at Pine Valley looked during Thomas's day.

3. Whenever given the chance, you always seem to stress the importance of strategy. Can you please concisely define what you mean by ‘strategy’ as it relates to golf course architecture?

The spirit of golf is to dare a hazard, and by negotiating it reap a reward, while he who fears or declines the issue of carry, has a longer or harder shot for his next play, yet the player who avoids the unwise effort gains advantage over one who tries for more than in him lies and fails.

Thomas's Fox Hills was full of strategic merit.

4. Do architects in the modern era implement this definition of strategy?

Well, the place I’m at now prevents us from actually playing your courses, but we do look down on them and seem to find an absence of basic thought-provoking elements. Even the most basic concepts of asking for placement of shots and understanding the value of different plays seems lost on both golf architects and the golfers. The man who knows the value of each of his clubs, and who can work out when it is proper to play one and when to play another, succeeds at the game. The ability of a golfer to know his power and accuracy, and to play for what he can accomplish, is a thing which makes his game as perfect as can be while a thinker who gauges the true value of his shots, and is able to play them well, nearly always defeats an opponent who neglects to consider and properly discount his shortcomings. I sense that the combination of technology, refined conditioning, the aerial game and the overall curiosity with fairness have combined to eliminate strategy. It appears you have a society willing to go to great lengths to avoid thought. I do see examples of strategy and enjoy the discussion by some of the architects, but they are fighting an even more difficult battle than my peers did in convincing golfers of its importance.

5. What was the inspiration for the bunker in the middle of the 6th green at Riviera?

There was no particular inspiration, just an opportunity to do something memorable with a one-shotter. No one can deny the lure, intrigue, and importance of the one-shotter. Particularly if they are built with care and a purpose which compliments the remainder of your design. In this instance, the green setting allowed for a large surface that would require a shelf through the middle, creating two distinct compartments. Instead of a classic two-shelf green, it afforded an opportunity to present something such as a bunker in the center where players on the wrong side of the green could still get around the hazard in two sound putts, which we decided would mute certain cries for justice. We understood that if the bunker proved too annoying, they could always fill it in and still have a fine one-shotter. However with the two compartments in one green, there is much skill and thought required depending on the placement of the hole or the location of the tee markers. You don’t find that very often in one-shotters.

6. Originally the 10th at Riviera had no greenside bunkering and then a year later you added it. Do you recall what drove you to change your mind? Has technology made the 10th hole even more dangerous today than when you first designed it?

The choice off of the tee was not posing the decision-making dilemma we had hoped for nor was it posing much difficulty for the so-called dubs. The player was a fool to lay safely to the left because the green was rather easy to play from the right side of the hole. The only option was to go straight at the green. But our intention was to create a better angle of approach by playing left from the tee, against what seemed to be the natural inclination to shorten the hole and play toward the green. So in November of 1928, I instructed the club to make some modifications, which they accepted since I had told them when the course opened that the bunkering was not complete and that there would likely be a dozen or more bunkers added after we had observed how the holes played. Interestingly, even with the new tenth hole bunkering scheme, the golfers still succumb to the temptation to play straight at the green. In my day, young Charlie Seaver, who was a member at Los Angeles Country Club and the son of my good friend, drove the tenth green while playing with Bob Jones in 1930. Jones was in town filming his short instructional movies, and he also drove the green. Had the new greenside bunkers not been there, both men could have driven their ball in a fairly imprecise manner and made birdie. With the new bunkers, at least they had to think a bit before slashing away, with only the long, precise drives rewarded.

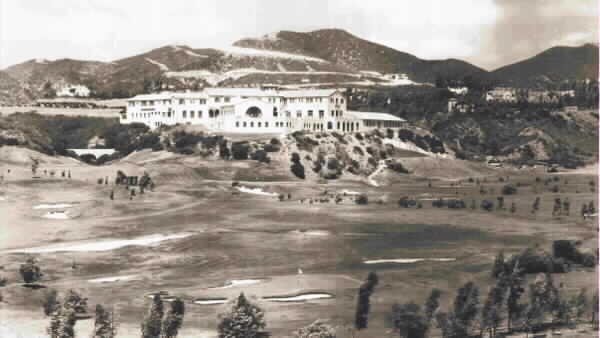

Looking back down the 10th hole to Riviera's famous clubhouse.

7. Riviera has resisted change more so than any of your other designs. What design features have helped to insure that technology has never rendered the challenge at Riviera ineffective?

The element of thought. Each hole was designed with ‘an intelligent purpose’ as my old pal Max Behr used to say. Giving the players options and tempting situations keeps them a bit off balance, even with the equipment they have today. The ability of players to understand the simple strategy of a hole is undoubted, but too often they play blindly and do not consider their best line of attack. On other holes where strategy is more involved, the player does not often discover his best line until he has played the course several times.

The barranca on the first hole at Riviera, circa 1927.

8. Why are changes being made to Riviera at the moment?

I suppose the attractive financial prospect of a United States Open is the primary inspiration, though I really think they should come up with some more parking places for spectators before they go renovating the course. If they had just kept the polo fields they wouldn’t be having this problem! I’m particularly amused by the willingness to exploit my name and ‘restoration’ and ‘what I would want if I were around today.’ Frankly, I don’t know what I would do if asked to make Riviera tournament ready as the game is completely out of hand. If you go back and read some of my articles from The Fairway and Pacific Golf and Motor, you will see I thought the ball situation was problematic in my day. It’s beyond comprehension now.

I assume it has reached this stage because of money. Golf strikes me as driven solely by money these days. The right to reap financial benefits from the game seems more vital than the rules, the values and the integrity of the sport. That is quite a contrast to my generation’s approach to the game. We had many interesting characters, a successful living for many who loved the game, yet we certainly did not treat the game like a stock. I left Drexel and my father’s beloved business because I could not stand the tunnel vision some have which prevents them from seeing recreational and artistic pursuits in a different light than basic business. They are one in the same today in sports, making for a complicated combination.

9. The second fairway at the 8th hole at Riviera is presently being brought back into play. What are your thoughts regarding the work that is going on at that particular hole?

Well, being a ghost, I can visit at any time, I just can’t play it. I don’t want to interfere, but I will suggest that visitors who play the finished ‘product’ ask themselves a few questions. First, do you sense you have options from a tee set at oh, about 430 yards, and if so, what do you gain by taking the right or left sides, and what do you risk by choosing one avenue over another? Are weighing such options even possible? Particularly for the average man, is such a yardage going to make for interesting golf the 51 weeks a year the course is in use? Can the average dub even play to the left hand fairway, which was intended to be his primary route? Also, I suppose Bill Bell would wonder if all that soil they used to prop up the alternate fairway really was the amount we had placed there before it washed down to the ocean in that 1938 flood? My guess is no, very little washed away, yet they have it quite high. Bill Bell certainly knew how to move and mask dirt in a natural fashion compared to the version they have erected which I suppose is a most peculiar interpretation of my work. It is a complex matter to handle soil and to grade it in a way that looks solid and natural, and few understand that this is the difference in the many timeless works versus the rather quickly thrown together efforts. Time, patience, care and years of study are required to create a grade that natural look.

10. Much has changed at Bel-Air and Los Angles North since your work there. What ten features (aggregate between the two) would you most like to see restored? Beside each answer, please note if it is still possible/feasible to do so and note if the expense would be excessive.

I try to avoid thinking of Bel-Air these days, it used to be such a gem. Do you know that some of Bel-Air’s members have the nerve to attribute the construction of those ornamental creeks to old plans of mine that were never realized? I say that with passion because Bel-Air was dear to my heart and to see it desecrated today is quite difficult. With that said, the first hole at Bel-Air must be returned to a getaway hole. It’s a freak of trees, creeks, sand and other nonsense today. The alternate options on the second hole worked quite handsomely in my day. The fifth featured a humorous little pitch shot that is missing from today’s courses. The ninth was another enjoyable short two-shotter. Well, that’s just the front nine. The incoming nine lacks the semi-blind green on the tenth, the alternate fairway eleventh, the Mae West mounds on twelve, the Redan features on thirteen, the enormous fronting bunker on the sixteenth, the dramatic character of the seventeenth ¦I’ve run on too long and we haven’t even moved east down Beverly Boulevard to LACC. Oh wait, it’s now Sunset Boulevard, excuse me.

As for Los Angeles, the North Course was on the verge of taking wonderful character with the four primary courses we could create within the integrity of the main design. I was quite proud of that setup, and when I look at a club event such as the Sartori at Los Angeles, and see that over seven days there is no real variety in the setup from day to day, I long for the possibilities of the multiple course setup possibilities. I once wrote that multiple routing was only in its infancy and was the answer to ‘supreme variation,’ but the idea apparently has not caught on. I’d also love to see the hazards on the North Course looking and playing more sternly. We did not envision grass manicured barrancas nor that rather blinding shade of white they have in the hazards today. It’s rather audacious, particularly for a club that prides itself for preserving the conservative lifestyle.

11. How did Billy Bell and you work together?

He supervised construction and I visited about once a week, as I was in poor health during 1926 and 1927. I visited more often for the projects on the Westside of Los Angeles of course, but he provided my eyes and ears on the construction site. Prior to construction, we worked together on routings, though he did not want to come up in my plane to survey the canyons for Bel-Air. He was a talented architect who opened my eyes to many possibilities in the construction field. Bell was also an innovator, creating the first sod-cutting machine that anyone in the West had ever seen, and he was also talented artist. He penned the drawings in Golf Architecture in America. It’s a pity his relatives did not see fit to keep them and his other renderings for future generations to enjoy.

12. What impressed you the most about Bell’s construction work?

His eye for drainage and the ability to incorporate drainage features into the design without most golfers knowing that the contours we created were there to move surface waters. Bell found a way to make some of the canyon sites and other odd properties here in Southern California drain effectively. We don’t get a lot of rain which I found wonderful for rose growing, but when we do get rain, it comes down in a furry, thus requiring these canyon courses to be able to move water out in a controlled manner. The rest of the year, we have these wonderful swales and valleys and ground features that add to the golf, thanks to the wisdom of Bill Bell.

13. Which hole that you designed which has been completely lost through time do you most wish was still around? What did you like so much about it?

The old sixteenth at La Cumbre was a treasure. It featured a heroic approach shot. The old Mae West at Bel-Air would bring out the ultimate in touch. I once said the third at La Cumbre was the finest I built, and I still feel that way. The par-4 that followed it was also excellent, but no longer exists today as I had built it. The par-3 third at Ojai was another favorite, I see they have returned it, though I’m curious about the scale of the bunkers they erected.

14. Were you and Doctor MacKenzie friends?

I first met the doctor in the spring of 1924 or 1925, I can’t recall for sure. We hit it off and found we shared nearly identical philosophies. We stayed in touch through letters and our mutual friend, Scott Chisholm, who had initially introduced him to Bill Bell and I. When the Riviera project started for the Los Angeles Athletic Club, I wrote to the doctor and asked him to stop in if he were ever in Los Angeles, so he could share his thoughts. Unfortunately, my words were misunderstood by Dr. MacKenzie, and he wrote in the British Golf Illustrated that he had been contracted to build a course for me. So when he arrived with a box of copies of his wonderful book, Golf Architecture, and then found the property under construction, we realized there was a misunderstanding. But he was a good sport about the whole thing until he sat down to write his book, The Spirit of St. Andrews. He voiced displeasure for the mashie course Bill Bell and I designed for the members to enjoy.

The Mashie Course that MacKenzie criticized.

15. Arguably, three of the top ten courses in America (Cypress Point, Pebble Beach, and Riviera) were designed (or severely modified in Pebble’s case) in the 1920s. Since WWII, no world class course has been built in California. Why do you think that is? Have issues like permitting, working with owners, etc. changed in Southern California since the 1920s? Do you see that changing?

If you go back and read many of the articles from my era, you will know that we had a similar problem back then. If it were not for Chandler Egan’s reconstructed Pebble Beach, Max Behr’s offerings (and writings), Norman MacBeth’s work, along with Dr. MacKenzie’s efforts, I wonder how the rest of the country would view California. There has always been less of an understanding of basic design principles in the West versus the East. One of the reasons I moved West was to express the possibilities of design and enjoy the better rose growing conditions. Back then, there was little excuse for the mediocrity when you consider the quality of sites selected for golf. Today, the process of building is more difficult and the quality sites apparently are not available, though I believe what some view as a poor site for golf, are actually quite fine. But I would also suggest that the lack of exposure to quality architecture continues to hinder the efforts of Westerners hoping to demonstrate the possibilities of golf architecture.

16. What features or design attributes do you find lacking in modern architecture?

I suppose the element of touch has been lost due to changes in conditioning, equipment, the addition of yardages everywhere you look, and the types of design presented. I wrote an article on the very subject of touch because I feel it is the quality that distinguishes the fine golfer from the average. It is impossible to play good golf without understanding touch. The sense of touch is the element in golf where the conscious mind grades the shot. All other parts of the stroke are produced by the sub-conscious mind, but the effort so made does not control direction, regulated distance or cut. This must be obtained by touch. Herein lies the secret of great golf “use the subconscious mind to produce the mechanical part as necessary as the fundamentals, and the stance and swing which create them. Complete the artistry of the perfect stroke by the addition of touch, which secures the superlative in exactness. Golf is a more interesting game when touch plays an integral role in the execution of shots, and I see less and less use of touch in the modern game.

In general, I believe that to thoroughly to enjoy golf, one should understand and appreciate something of the theory and strategy of the course.

The End