Feature Interview with Wayne Morrison

Restoration of The Country Club

Pepper Pike, Ohio

July, 2023

1. Please provide a brief history of The Country Club in Pepper Pike, Ohio.

The Country Club was founded in Glenville, Ohio, near Lake Erie in 1889. More than 130 years later, it remains true to its founders’ purpose – providing a country retreat for elite Cleveland families. Samuel Mather introduced golf to the Club in 1895, shortly thereafter a 9-hole course was created which was expanded to 18 holes in 1913. The members took to the sport in earnest, playing an important role in the development of golf in America. Coburn Haskell had a profound influence on golf and golf architecture with his invention of the rubber-wound “Haskell” golf ball which flew straighter and longer than gutta percha golf balls. The impact of the industrialization of the Glenville neighborhood and the increased distance of the golf ball required the Club to abandon its Glenville property and relocate to its current location in Pepper Pike.

William Flynn was engaged in 1928 to design a modern, what he called “scientific,” golf course for The Country Club. The firm of Toomey and Flynn was hired to construct the course according to the detailed plans developed by Flynn. In addition to being one of America’s finest golf architects, Flynn was also a leading expert on agronomic practices for golf and golf course construction. Flynn’s local design work at Pepper Pike Club and Elyria Country Club, in addition to his design and construction efforts at Merion Golf Club, Pine Valley Golf Club, The Cascades, Kittansett Club, The Country Club in Brookline, and many other nationally recognized designs, were factors in his selection.

The Country Club is one of the finest examples of realizing the full potential of the natural features of the grounds for golf. Flynn was one of the finest routers of golf courses in America and was particularly adept at utilizing interesting playing angles and creating site-specific unique holes such as the world-class holes twelve, fifteen, and seventeen at Country. This lay of the land style of architecture results in a distinctive and well-regarded design from the outset. Opened for play in 1930, the Club was awarded the US Amateur, the premier golf event of its era, a mere five years later. That 1935 US Amateur was won by Lawson Little, who for the second year in a row, won both the British and American Amateur championships. Coincidentally, Little won the 1934 US Amateur at the other Country Club in Brookline, which was mostly designed by William Flynn. I imagine Little developed a fondness for Flynn courses. The Country Club has also hosted the 1934 NCAA Championship and, more recently, the 2012 US Women’s Amateur.

The Country Club

2. Tell us about golf architect William Flynn (1890-1945)

When discussing the greatest golf course architects of all time, the focus tends to fall on names like Harry Colt, Alister MacKenzie, Donald Ross, A.W. Tillinghast, and C. B. Macdonald. One who is often overlooked is William Flynn.

Like many of the great architects of the Golden Age, William Flynn was a decorated golfer. Flynn grew up in Boston and regularly competed in school with the great Francis Ouimet, often beating him. Flynn’s career in golf got a significant boost when he was hired by Hugh Wilson as a construction supervisor and later green keeper at the Merion Cricket Club’s two courses, later known as Merion Golf Club’s East and West Courses. There, he became a close confidant of Wilson and had an instrumental part in the design evolutions of both the East and West courses.

Flynn with Nelson and Hogan, 1939

The crown jewel of Flynn’s design portfolio is Shinnecock Hills Golf Club, but the depth of his portfolio of courses is equally impressive with great courses such as Cherry Hills Country Club, the other The Country Club (MA), The Kittansett Club, Indian Creek Country Club, Philadelphia Country Club, and Lancaster Country Club as well as substantial collaborative work at Merion Golf Club’s East Course and Pine Valley Golf Club. Flynn’s innovative designs for the estate courses of the Rockefeller, Cassatt, Woodward, McLean, and Lasker families contained crossover holes, reversible holes, and double greens that are only functional for private estate courses with their limited play.

Flynn was one of the most forward-thinking architects, evidenced by how many of his golf courses retain their original designs and remain challenging for all classes of golfer a century removed from the original designs. In 1927, Flynn wrote an article for the USGA Green Section Bulletin stating, “All architects will be a lot more comfortable when the powers that be in Golf finally solve the ball problem…If, as in the past, the distance to be gotten with the ball continues to increase, it will be necessary to go to 7500 and even 8000 yard golf courses and more yards means more acres to buy, more courses to construct, more fairways to maintain and more money for the golfer to fork out.” This knowledge instilled upon Flynn to design elasticity in his courses, allowing them to be more easily lengthened. In doing so, his courses stand the test of time despite significant advances in implements and player improvement.

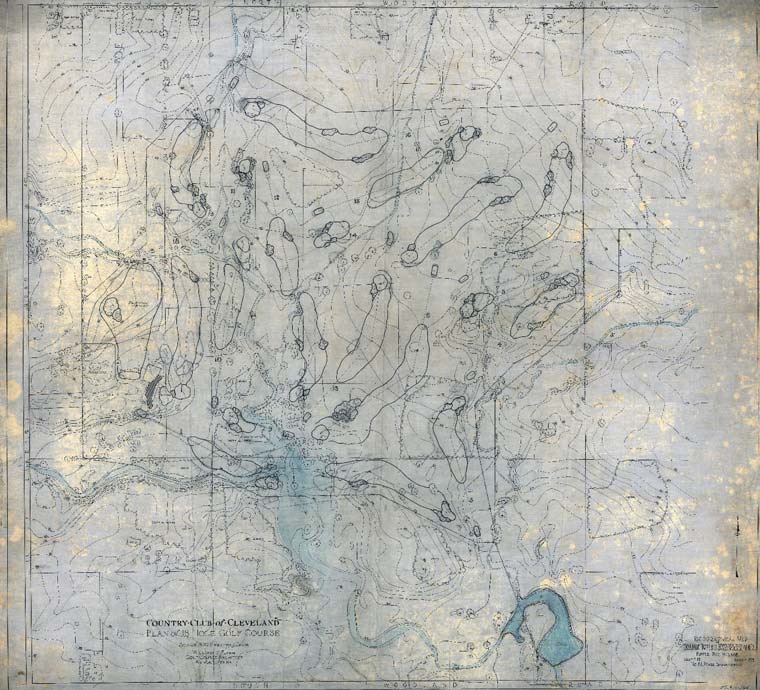

Routing – Flynn’s strongest skill was his ability to route a golf course and he did so well, he is often regarded as possibly the finest of all-time. Flynn’s routing philosophy was rooted in selecting the greens first and connecting the holes from there. His routings came from meticulous mapping, planning and a great understanding of the land for his sites due to his extensive time on site. The routing at The Country Club provides a rhythm and flow to the round with an overall strength of holes that peaks on the back nine with a set of memorable finishing holes, especially after the home hole has been restored to Flynn’s initial design intent.

Naturalism – Along with routing, Flynn’s forefront skill was his ability to blend heavily engineered areas with their natural landscape. Fairway approaches meld seamlessly into the greens. It is only when you consider the full 360 degrees around the greens that the architecture reveals itself. Bunkers sit naturally in the ground with the appearance of wind and water erosion rather than a manufactured look with geometric outlines.

Strategy – It wasn’t uncommon for Flynn to test players with approach shots that called for the opposite shape shot which the slope of the fairway yielded. The natural instinct for long hitters is to cut the corner of dogleg par-4 and par-5 holes. But rather, Flynn often designed dogleg holes which rewards the thoughtful and accurate player who can place the ball on the outside of the dogleg to leave the ideal angle of approach to the green. The third and eighth holes at Country are excellent examples of the ideal approach being on the outside of the dogleg. For the golfer with a keen eye for the strategic intent of the golf architect, green orientation, greenside bunkering, and hazard locations, they will realize that strategy is dictated from the green all the way back to the tee shot.

Shot-testing and Variety – Flynn was one of the early proponents of having multiple tee boxes for use on a daily basis providing an appropriate test for a range of golf abilities. Flynn gradually adopted the use of short grass around greens with the finest examples found at Shinnecock Hills Golf Club. He believed that it would lead to a greater variety of recovery shots that a player would need to possess in their short game. Offset fairways and greens test both line and distance determinations for the ideal approach angle off the tee and into his greens. Nowhere is this more apparent than the tee shot on the soon-to-be renowned seventeenth hole at Country.

Green sites were constructed in such a way that they blend harmoniously into their surroundings. Long interplays of slopes and a subtle but repeated use of perceptual miscues adds drama and increases the requirement for strategic thought and execution.

If avid golfers and avid golf architecture historians alike were asked to name the golf architect whose accomplishments are listed below, only a small percentage would recognize them as contributions by William Stephen Flynn.

- Was an expert in golf course design, construction, agronomics, and maintenance;

- Was one of the leading researchers in turf grasses for golf;

- Published a series of articles in the USGA Green Section Bulletin on golf course architecture and construction;

- Lectured at Penn State’s turf school, one of the finest in the USA;

- Started a golf course construction company that built some of the most important golf courses in the classic era of golf architecture;

- Was one of the first golf architects to use multiple tees meant for different classes of golfers;

- Originated the use of runway tees, some nearly 100 yards long, decades before Robert Trent Jones;

- Though he only worked on 81 course projects with less than 60 remaining today, 111 USGA events and three PGA Championships have been played or are scheduled to be played on these courses;

- Implemented the principles of scientific management developed by Frederick W. Taylor to the design and construction of golf courses;

- Designed, in whole or in part, 11 courses in Golfweek’s top 100 classic courses;

- Innovative routings that utilize natural features as much as possible, and where necessary, mimic natural features which serve to create site-specific designs costing less to maintain;

- Pioneered the use of triangulation in routing to enhance the changing effects of wind throughout the round;

- Enhanced the effect of perception to effectively deceive golfers in terms of angles and distance.

Unlike Tillinghast, Behr, Travis and Macdonald, Flynn’s writings on golf were found in industry bulletins, not popular press. As a result, Flynn did not receive the national recognition that other architects enjoyed.

Unlike many of his contemporaries, Flynn was a blue-collar man (though he married into a distinguished Boston family) and rose in the golf industry through talent and personality. Yet the “wild and mild Irishman” was readily adopted by the elites of Philadelphia society, Rockefeller, Geist, Woodward, McLean, and Lasker.

Flynn jokingly called himself The Nature Faker. Flynn hid his handiwork by making manmade features look natural thus making it difficult to determine the extent of his work at a given site leading to a misinterpretation in the amount of architectural input.

Flynn’s courses (design and redesign) were geographically concentrated particularly in the PA-NY-NJ region. They are overwhelmingly private courses. Many are the elite courses in the region and so not frequently visited. He designed and built a few resort courses, most of which no longer exist (NLE). These public access courses include the Cascades and Old Course at the Homestead Resort, Boca Raton North and South (NLE), Opa Locka (NLE), Ritz Carlton North and South (NLE), and Seaview Pines.

William Flynn and the Four Elements of Golf Architecture that Enhance Character

Routing – The routing of a golf course is not entirely dictated by topography, as evidenced by a comparison and contrast of the William Flynn routing (not awarded) and the Donald Ross routing (awarded) at the Country Club of York. On that rolling site, Flynn and Ross utilized the land very differently.

Routing the golf course is solving a puzzle with the final plan providing the most interest and challenge to all classes of golfers, ensuring there is a flow and theme to the golf hole sequencing, while also being sustainable in terms of resources and drainage. George Thomas wrote, “The greatest care must be taken to secure the full value, with the least congestion, moderate expense in construction and other necessary fundamentals. The proper solution is much on the order of a chess problem; the first effort is not generally the best… Slopes, hills, mounds, or any other contour which affect the roll or run of the ball, are aids on all parts of your fairway and your strategy should, if possible, hinge on them.”

There are patterns that golf architects tend to follow, some more closely than others. Once the type of course, clubhouse site, parking, practice ground, entrance road, etc. was discussed with the Club, William Flynn felt he was free to proceed unhampered with the layout. Flynn felt it necessary to have a topographical map showing accurately the location of trees, streams, fence lines, walls, and buildings plotted. The topographical map will, to the trained eye, indicate drainage issues, how the irrigation system is to be planned, the clubhouse location, and ultimately, the hole locations.

Greens – The most important aspect of designing golf holes is to select proper green sites. The first condition in site selection, the adaptability of the site for the particular hole being contemplated. Second is the question of the cost of construction. Third is the beauty both in background and vistas. Flynn would select his greens first and then work backward to the tees, radiating in all directions from the green until he secured the optimal routing progression. Flynn worked with a more detailed survey of the green sites in one-foot contours. He was then able to blend the green into the surroundings while presenting a natural effect.

Flynn thought it not advisable to copy the green designs of famous holes from abroad and adapt them to a particular hole. He believed a successful architect would not follow that system. He felt his greens should be born on the ground and made to fit naturally on each particular site while avoiding similarities. Flynn believed that the added upfront expense to construct a natural looking golf course would be offset with subsequent maintenance savings.

Bunkers – Flynn believed that bunker design is a critical component and one that is most noticed by golfers. He carefully considered the exact location of fairway and greenside bunkers so that they are visible. Flynn felt that a concealed bunker has no place on a golf course because it does not register on the player’s mind and thus loses value. There are, of course, exceptions such as the second left fairway bunker on the fourth hole at Merion’s East Course. Flynn believed the best-looking bunkers are those that are gouged out of faces or slopes, particularly when the slopes face the player and “stand out like sentinels beckoning the player to come on or keep to the right or left.” Flynn designed and built bunkers that appear naturally formed by wind and water erosion with resulting irregular shapes. An important condition in the design of Flynn bunkers was that they surface drain.

Gil Hanse quoting Bill Kittleman on Flynn’s simplistic bunker style: “It’s easy to build complicated bunkers, anyone can do that. The beauty of building simplistic slowly ascending, slowly descending lines and to make it look good and to make it feel like it is part of the context of the golf course without it having to look too simplistic – there’s a really fine line.” Gil’s challenge at Country was, in his words: “How do we build bunkers that are so simple yet still have the appearance that they are graceful in the landscape as opposed to just some ‘satellite dish.’”

Scale – Scale is an important element of design, whether or not it is art, fashion, or golf course architecture. Scale can inform and mislead the player depending upon its application. Large bunkers appear closer than in actuality. Small bunkers elongate the distance perspective. Long, gradual elevation changes are hard to discern, especially without distance cues that trees and other familiar features provide. Tree lined fairways tend to look narrower than they really are.

Flynn was a master at utilizing scale to keep the golfer thinking and potentially off balance. He manipulated the toplines of bunkers to distort distance perception and angles. In the case of greenside bunkers, toplines were designed in some instances to distort the perceived slope of the green.

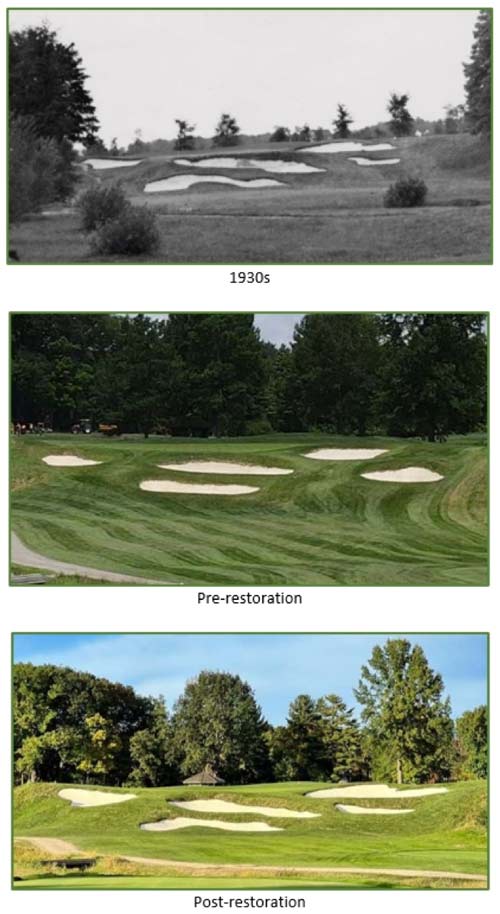

At most classic era golf courses, over time, some of the playing angles and strategic shot demands have been lost due to fairway shifts, bunker placement, and lost green space. When vistas are restored, such as occurred at The Country Club, topographic interest is once again revealed and highlighted. The restoration of the size and natural shapes of the bunkers will have a marked effect on the golfers playing the newly restored course enhancing the need to execute both the mental and physical examination of the golf course.

The Country Club is one of the finest examples of realizing the full potential of the natural features of the grounds for golf. The Country Club golf course is a rare sort of design. Set on 240 acres, the routing provides a rhythm and flow consisting of strategic hole designs for all classes of player with a constant change of direction throughout the round enhancing the effect of wind on shot shape and placement. Flynn was perhaps the finest router of golf courses and particularly adept at utilizing interesting playing angles and creating site-specific unique holes such as holes 12, 15, and 17 which are all-world in quality and uniqueness. This lay of the land style of architecture resulted in a distinctive and well-regarded design from the outset.

A round of golf at Country introduces the player to a marvelous collection of challenging long and short par 4s, a set of outstanding par 3s, and strategic par 5 holes. Flynn and Colt arguably were the two finest designers of par 3s in world golf and you will find an outstanding set of par 3 holes at Country. There is not a lot of elevation change on the golfing grounds at Country, but nowhere will you find a better use of the available topography as at Country.

Flynn March 1928 routing

3. What work did the Club determine was required for the long-range master plan?

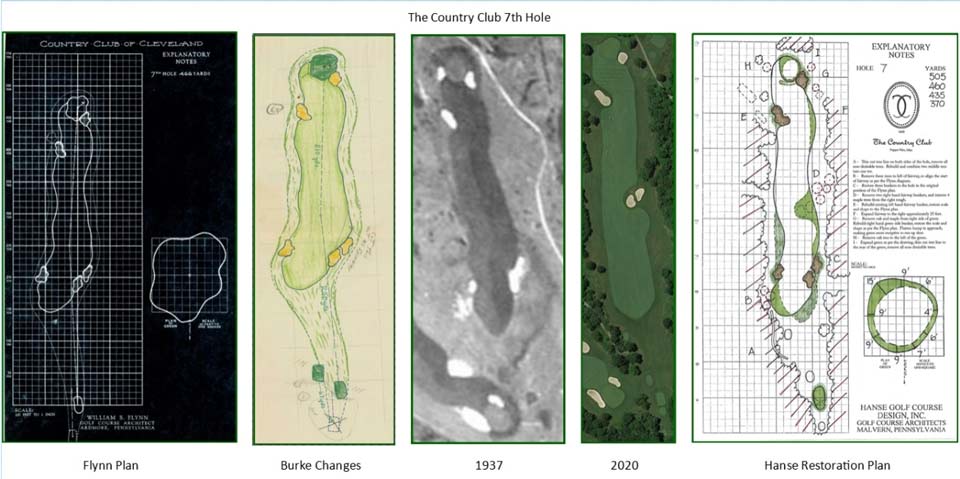

Over time, some of the playing angles and strategic shot demands have been lost due to tree proliferation, fairway shifts, bunker additions, and alterations, and lost green space. Bunkers, like most components of a golf course, have a limited life span. The Country Club governance committees recognized that the bunkers needed to be rebuilt so I was contacted to provide a historical perspective. I am a member of the Archives Committee at Merion Golf Club specializing in golf course architecture, one of the founders of the USGA Golf Architecture Archive, and an expert on William Flynn (co-authored, along with Tom Paul, The Nature Faker, a 2,548-page book on Flynn). I have had the honor to provide historical restoration research and consultations for a number of important clubs including Shinnecock Hills Golf Club, Merion Golf Club, Philadelphia Country Club, The Cascades Golf Course, Huntingdon Valley Country Club, Springdale Golf Club (Princeton University), Blair Academy Golf Course, and others. I was asked to take a look at the planning, construction, and evolution of the course with specific regard to the bunkers, which had reached the end of their lifespan. Country member Mike Gleason and I worked together to prepare a hole-by-hole evolution report showing what was planned by Flynn, what was built by Toomey and Flynn, and the architectural changes which took place over time.

From that exercise, it was evident that additional issues, beyond bunker restoration, should be addressed for a comprehensive and accurate historical restoration. These elements include green expansion, adjusting fairway lines, improving drainage, regressing of fairways, and tree management. Extensive tree plantings and the alterations made by Club golf professional Billy Burke in the mid-1930s, which included bunker additions, were targeted for removal. For a time, elevating tee boxes for visibility was in vogue. These alterations to the landscape were removed with a number of tees restored to the natural grade.

In moving the 18th green to lengthen the hole according to Flynn’s initial plan, the short game practice area was sacrificed and had to be moved. The Club determined to relocate their platform tennis facility next to their tennis facility so that ground and more was repurposed for an expanded practice facility designed by Gil Hanse.

4. How was the restoration process structured?

The Club organized a Restoration Committee reporting to the Green Committee that was responsible for determining the mission statement, hiring the consulting golf architect, developing a budget, and then implementing the plan within the governance framework of the Club. The Restoration Committee consisted of Chairman Clarke Jones, Green Committee Chairman Bob King, Mike Gleason, and Club President Sam Knezevic. Along with head golf professional, Steve Bordner, Grounds Superintendent Brian Mabie (since retired), and General Manager and COO Eli Edgerly, the Committee determined that a historically accurate restoration plan was to be implemented along with relocating the 18th green to the original location planned by Flynn but constructed short of that location due to anticipated plans for the clubhouse.

Given that historic accuracy was to be the foundation for the project, all archival assets available were assembled including detailed individual hole plans and routing maps with topographic lines prepared by William Flynn along with a series of historic aerial photographs, and correspondence between the Club and Flynn. These assets provided the Restoration Committee, consulting architect Gil Hanse, and his Hanse Golf Course Design team with the materials needed for an accurate historic restoration. The mission was to recover the original design intent and lost strategic elements with an aim to garner national attention for the distinguished design which the Club holds in such high regard.

The Club’s Restoration Committee interviewed several distinguished golf course restoration specialists and afterwards was excited to be able to come to an agreement and engage Hanse Golf Course Design, Inc. to oversee the restoration program. Gil Hanse is one of the most sought after and most accomplished golf architects with an impressive portfolio of original designs and historic restoration projects. He has been entrusted with the restoration of some of the nation’s finest courses including Merion Golf Club, Oakmont Country Club, The Country Club in Brookline, Los Angeles Country Club, Oakland Hills Country Club, Baltusrol Golf Club and Winged Foot Golf Club to name just a few.

Gil’s artistry, craftsmanship and attention to detail was put into full effect at Country. The golf course architecture had lost its scale over time. Trees grew while greens, fairways, and especially bunkers had significantly gotten smaller. During the restoration project, all the bunkers were increased in size to restore the original dimensions, some doubled in size. Bunkers added later by Billy Burke and others were removed. Tree removal opened up longer vistas which now highlight the unique landforms Flynn brought into play. While the golf course doesn’t play dramatically differently after the restoration, the course is bigger, bolder, and more visually stimulating than before. Gil’s vision and work enhanced the Club’s most vital and significant asset which will surely benefit their membership, guests, and tournament players for decades to come.

The Club’s mission has remained unchanged through the years, that is to provide the finest facilities for its members and guests. The process which was followed and detailed below ensures that the mission is sustained for decades to come.

5. What are some advantages of working with a golf architect historian in general and regarding William Flynn specifically?

Architects that either recommend or are tasked with historic restorations may benefit from working with a golf architecture historian. A consultant with the time and research assets on hand can provide critical evidence of what was planned, what was originally constructed, and the changes that occur over time. Over the last 20 years or so, I have either completed the research work required or have the methodology to efficiently collect additional information from libraries, Internet resources, historical societies, county or township records, and a network of fellow researchers such as Craig Disher for access to his historic aerial collection. Governance committees are often receptive to working with a consultant to help educate the membership and assist in the restoration process.

Restoration projects by William Flynn benefit, perhaps more than other classic era architects, with historic consulting. The collection of detailed Flynn drawings represents the most comprehensive record of any classic era golf course architect. I have assembled a large collection of historic aerial photographs, many taken shortly after the courses were built and some, such as at Shinnecock Hills Golf Club, taken during construction. Based upon these assets, we can determine that Flynn accurately drew his plans, and the courses were built precisely according to those plans.

One of the most effective methods of helping committees and consultants is to provide a hole-by-hole analysis with side-by-side images of plans, old aerials, and modern aerials to effectively demonstrate the evolution of the golf design. Overlays of drawings and aerials show in two dimensions what work would be required for a historic restoration.

Evolution of the 7th Hole

Overlay of Flynn’s plan and aerial photograph

Having been involved in various capacities on prior restoration projects, it is evident that there are significant advantages to working with a historian, particularly in cases where historic accuracy is the goal. There are many examples where the lack of reference to historic assets and consultant input yields inferior results. However, the foundation for a successful project rest with the consulting architect and their relationship with the construction team.

6. Flynn’s design portfolio is rather limited as compared to Donald Ross (430 courses) and A.W. Tillinghast (approximately 200 courses). This allowed Flynn to spend a considerable amount of time on site relative to his contemporaries. Did he do so at Country and if so, in what ways did that benefit his design there?

Cleveland was an important industrial and commerce center in the 1920s and the commissions in that district were highly sought after. Flynn designed three courses in the region. The Pepper Pike Club opened for play in 1925, the Elyria Country Club also opened in 1925 and then The Country Club, opening in 1930. Country shares a common border with The Pepper Pike Club property. Flynn spent a lot of time in Cleveland working on all three of these elite projects with many of the same members.

Flynn wrote that a golf course architect could not mass produce quality golf designs. He believed the best and most cost-effective method was to spend a lot of time on site developing multiple iterations on paper before coming up with a final set of plans. He was thus able to maximize the potential of a site because of the amount of time spent on site while minimizing change orders and time to completion.

For a site with only seventy-five feet of elevation change and few topographic features, Flynn’s extensive time on site allowed him to maximize the utilization of the streams and ridges to provide aesthetically pleasing holes with high degrees of strategic interest.

7. William Flynn’s golf courses in and around Philadelphia are what most people think of when it comes to Flynn designs. What comparisons and contrasts are there between The Country Club and those in Philadelphia?

The Country Club golf course and club would feel right at home with the parkland courses around Philadelphia with one exception. Flynn had nearly 250 acres to lay out his 18-hole golf course in Pepper Pike whereas Flynn had significantly less acreage for most of his courses in the Philadelphia suburbs. Restoring the large scale of The Country Club course with fairway, bunker, and green expansions and tree removal once again showcases the quality of the grounds for golf. Like the Philadelphia area courses, The Country Club routing uses a variety of angles to approach interesting landforms and streams.

Flynn’s original designs at Philadelphia Country Club, Lancaster Country Club, Huntingdon Valley Country Club, and at Merion Golf Club’s East Course and Pine Valley Golf Club, where he worked and was clearly influenced, have a rhythm and flow to the routings that lead up to a spectacular finish. In the case of The Country Club, holes twelve through eighteen include some of the best holes on the course and in holes twelve, fifteen, and seventeen, some of the best holes in American golf.

The Country Club, like some of Flynn’s more renown courses, has varied approaches rewarding specific shot demands, and is without any weak holes. Ran likes to ask himself after playing a course which are the three weak holes. With Flynn designs, that poses a very difficult question to answer as typically the collection of holes are strong from one to eighteen.

Flynn liked to employ visual deception in his designs that test the golfer’s strategic decision making to overcome perceptual miscues. Flynn was an expert at creating interesting playing angles, often in opposition to standards of the day such as designing optimal approach angles from the outside of doglegs. This is evident at Rolling Green Golf Club, Merion East’s first hole (designed by Flynn), Huntingdon Valley, and elsewhere. This design philosophy is evident at Country as well. Consider the third hole; the restoration of the bunker sizes and shapes seem to stack and surround the green from the right side of the fairway. The scale of the bunkers makes the green look like a much smaller target when played along the shortest line to the hole. If the tee shot landing area is on the outside of the hole (left side), which the recent fairway expansion to the left allows, the view of the green is not as obscured, and play is along the long axis of the green. On the eighth hole, if the second shot is not played out to the left, the green is obscured by a mound with three bunkers cut into the upslope.

One aspect of golf design that Flynn did not incorporate at Country was his preference to design par 3s that required a driver. On opening day, the longest par 3 was the slightly downhill fifth hole at 200 yards. Today, the longest par 3 is the 215-yard par 3 fourteenth hole.

Hole 8 approach from right side of fairway

Flynn was a master at routings that utilize meandering streams, especially on diagonals throughout his entire portfolio (Philadelphia Country Club, Lancaster Country Club, Huntingdon Valley, Lehigh Country Club, Cascades Golf Course, Rolling Green Golf Club, etc.). Flynn utilized strategic crossing and lateral streams at The Country Club on the par 4 first (fronting the green and approach apron), the par 3 ninth (diagonal along the right), the par 4 tenth (on a diagonal fronting the green and approach apron), the par 5 twelfth (the crossing stream was piped over) and the par 5 second and par 4 eighteenth have crossing streams off the tees.

8. Greens often shrink over time, especially on courses as old as The Country Club. What was the average percentage of green expansion?

The prior work on the golf course recovered a substantial amount of lost green space. The average percentage of green expansion in Hanse’s project was around 20%.

9. What are some of the advantages to recovering green space?

The ability to restore the relationship between the edge of the green and the surrounds is critical. In areas where there are several yards of rough between the edge of the greenside bunker and the edge of the green, the ball might not get in the bunker and instead get hung up in the rough. Flynn’s original design at The Country Club intended for that green to be much closer to the bunker edges. While it doesn’t sound like much, if you are able to move the hole locations even several steps closer to the edge, you’ve created more intensity to the approach shot due to the greater challenge and the avoidance of near misses.

10. The back nine is often highlighted in any conversation about The Country Club. What holes on the front nine are of particular interest?

The second hole was initially planned as a long par 4. In the final version, Flynn laid out a dogleg right par 5 with a tee shot that crossed a stream to an uphill landing area framed by two bunkers and a ridge along the right-side sloping right to left into the fairway. A bunker in the side slope can be carried by long hitters now that a number of mature trees were removed from the hillside to restore the hole as designed and built by Flynn. A Bunker short and left of the green, curiously behind a tree was put in sometime between 2003 and 2004. This was removed allowing approach shots that miss left, to fall away from the green.

Hole 2 before restoration

Hole 2 after restoration

The third hole has a slight dogleg to the right with the optimal approach angle from the left. The First bunker in the image below is predominantly along the line of play but it looks like it is perpendicular to the line of play. The enlarged bunkers appear stacked making the green look smaller than it actually is.

Hole 3

The front nine finishes with the medium length par 3 ninth hole with the clubhouse in the background. While the bunker outlines lack the flourish found in Mackenzie bunkers, the simplicity of the forms appear elegant. The short grass approach area was expanded and brought closer to the stream short of the green.

Hole 9

11. Please describe some of the holes on the back nine that garner the most attention.

Flynn had a propensity to place medium length par 3 greens on ridges increasing the demand to hit a precise uphill shot. A superb example of this is the eleventh at Shinnecock Hills Golf Club. Hanse’s green expansion on Country’s eleventh hole allows shots to utilize the back of the punchbowl-like green to bring the ball back towards the hole. The bunkering on the hillside below the green was expertly restored. While still simplistic, the interesting shapes naturally fit into the surrounds, appearing eroded rather than artificially created. The impact of these five bunkers significantly weighs on the mind any golfer standing on the tee.

Hole 11

The par 5 twelfth hole demonstrates Flynn’s ability to draw the most out of the natural landforms on a site. The tee shot plays to a wide fairway with no bunkers or hazards in play. The fairway is interrupted by a falloff to a lower level where there was once a stream that crossed the fairway, now piped underground. The green sits on an extension of a ridge with falloffs front and right.

12th green before restoration

Hole 12 green after restoration

Flynn wrote of the highly strategic par 4 fifteenth hole:

“The tee shot is played into the valley through a sighting gap. The green is on a rise about 25 feet above the drive area with an abrupt slope acting as a carrying hazard between. Large pits are torn out of the face of the bank increasing the mental hazard while the pit at the left of the green forces an accurate second shot. The long player can take the direct line across the diagonal bank. The shorter player may carry across the pit to the right, or short side of the carry, and get on with an easy three.”

The elevated tee boxes were lowered, and Flynn’s “sighting gap” restored. The approach shot is to an angled fairway elevated above the cross bunkers. The green slopes back to front with an elevated bunker behind the green, similar to Flynn’s first hole at Merion East.

Hole 15 prior to restoration

Hole 15 after restoration

Hole 15 and the restored “sighting gap”

The seventeenth hole is one of the finest short par 4s in American golf. The tee shot is played across a valley uphill to an offset fairway that is significantly contoured. Trees were removed on the left near the stream and behind the green eliminating distance cues on the approach. The left rear bunker added by Billy Burke was removed increasing the risk of missing the approach to the left.

Hole 17 prior to restoration

Hole 17 from the tee after restoration

Hole 17 approach after restoration

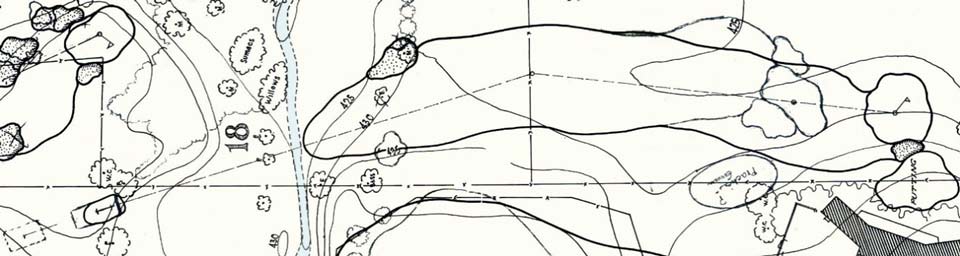

Flynn designed two iterations for the eighteenth hole, initially at 450 yards with the final version playing to 393 yards. The change was likely due to considerations for the clubhouse and pool location, whose plans were not completed at that time. Flynn is known for his long and demanding finishing par 4 holes influenced by Merion East and Pine Valley and found at many of his original designs, including the original home hole at Philadelphia Country Club (current 3rd), Huntingdon Valley, Lancaster Country Club, Cherry Hills Country Club, Indian Creek Country Club, Kittansett Club, the original at Woodcrest Country Club, and Pepper Pike Club.

Prior to the restoration, the hole played as a 445-yard par 4, considered a short par 4 in today’s game. Post restoration, the hole is a stout 510 yards long. Not only did the lengthening make the hole more relevant as the finisher but there was an advantage to moving the former practice green to make room for the final green. The result being that the former busy practice green activity, which distracted the view from the clubhouse terrace, the first tee, and the eighteenth green, was relieved with the focus now only on golf being played on the course. The right fairway bunker at the start of the fairway was restored along with the flanking left fairway bunker. A second left fairway bunker, not original to the Flynn plan, was removed.

Flynn’s plan for Hole 18

Hole 18 prior to restoration showing the practice green, now the approximate location of the 18th green

Hole 18 tee shot

Hole 18 prior to restoration

Hole 18 post restoration

12. Please describe the routing at The Country Club.

Flynn had a definite tendency to enhance the effect of wind in his routings. At Shinnecock Hills, he varied the direction of wind in play through a series of triangles. At Huntingdon Valley, he routed the holes in a clockwise outer loop and then a counterclockwise inner loop. The wind off Lake Erie has a significant effect on play at Country. Flynn used the routing here to vary the wind direction throughout the round. The tree management program helps to increase the effect of wind requiring careful consideration on distance and shot shapes.

The front nine at Country runs counterclockwise, playing downhill 30 feet from the first tee then rising gently to the fourth green, then falling gradually down to the ninth green which is at the same elevation as the first green. The back nine changes direction and elevation a bit more. Holes ten through twelve plays clockwise followed by holes thirteen through eighteen playing counterclockwise with the most interesting landforms incorporated during this final stretch.

13. Some think that The Country Club is among the finest original designs by Flynn. What characteristics does the course possess that may support such a significant claim?

The following characteristics are emphasized by Flynn and are found throughout Country’s golf course.

Character – The Country Club course contains unique features below the stately clubhouse with commanding views of the course. Landforms are optimally used to create one-of-a-kind world class golf designs, width with hazards and green complexes that enhance strategic thought, and playability that effectively showcases the architectural demands intended by the golf course architect. Flynn wrote in 1923, “An architect should never lose sight of his responsibility as an educational factor in the game. Nothing will tend more surely to develop the right spirit of the game than an insistence upon the high ideals that should inspire sound golf architecture. Every course needs not be a Pine Valley or a National, but every course should be so constructed as to afford incentive to and provide a reward for high-class play; and by high-class play is meant, simply the best of which each individual is himself capable.”

Interest – Flynn wrote in 1927, “The principal consideration of the architect is to design his course in such a way as to hold the interest of the player from the first tee to the last green and to present the problems of the various holes in such a way that they register in the player’s mind as he stands on the tee or on the fairway for the shot to the green. The principal thought in designing a course is to produce 18 interesting holes with a variety of play. A course which has variety of play and character in its natural state can be readily made more interesting by the installation of a limited number of man-made hazards.”

Flynn wrote later that year, “To boil down the science of Golf Course design, the Architect’s job is to provide eighteen distinctly different problems or types of holes insofar as it is possible to do so. Problems that hold the interest of the player, that offer incentive, and provide a reward for his best golf whether he be the low handicap man or the one who shoots well over a hundred.”

In this regard, Flynn provided golfers with a variety of shot tests utilizing natural and artificial hazards. Since all golfers are not alike, Flynn’s design at Country and elsewhere allow each player to employ a strategy prescribed for their particular game.

Naturalness – Flynn wrote, “The most important consideration in conjunction with the designing of a green is to create naturalness. Of course, this condition can only be brought about as construction progresses, but the framework must be right in the beginning. Naturalness should apply to all construction on golf courses, greens, tees, mounds, and bunkers alike. It is much more expensive to construct a natural looking golf course on account of the tremendous amount of material that must be moved, but the money saved in the subsequent maintenance greatly offsets the original cost.”

When playing the golf course at Country, there is a sense, consciously or not, of connection to the land. The greens and bunkers lie seamlessly on the ground. It is no wonder the membership has such an emotional tie to their site. So much so that Gil Hanse and his team readily recognized the affinity of the members for their grounds for golf.

Subtlety – Flynn was perhaps the master of subtlety. The subtle nature of his designs does not lend them to immediate understanding or compelling photographs. His design theories are not readily apparent and often require extensive play to fully appreciate the imagination and implied strategy. Yet under multiple plays, they do reveal their elegance and complexity.

Flynn’s greens exhibit apparent simplicity but actual complexity with their long interplays of slope rather than overt undulations. The bunkers are expertly paced with apparently simple outlines. As Gil Hanse remarked, “What gave us consternation was the simplicity of the bunkers…we all love the frilly edged and eroded bunkers like MacKenzie and we want to build these beautiful bunkers on our original work, and there [at Country] the simplicity of Flynn’s lines was just amazing how simple they were. And Bill Kittleman, who is a great mentor to Jim [Wagner] and me, the former pro at Merion…he always challenged us. So, we spent a ton of time talking about that… Here it was like, ‘Nope – tone it down, we have to tone it down. We kept having to rack our brains…that was an interesting lesson for all of us.”

Fun – A course should be fun to play, even championship courses. It is easy to build a difficult golf course. Flynn was a masterful in building enjoyably difficult golf courses, ones that appeal to all classes of players.

14. The Country Club course is nearly 100 years old, what was the rationale for a historic restoration rather than a renovation given the changes in the game over time?

The simple reason is that a historic restoration was possible. All the archival materials necessary to restore the golf course back to its original form were available – either at the Club or provided by me. Flynn was one of the great golf course architects in America. He understood the test of time demands and the grounds for golf at The Country Club are ideal for a design that is enjoyably challenging for all classes of golfers.

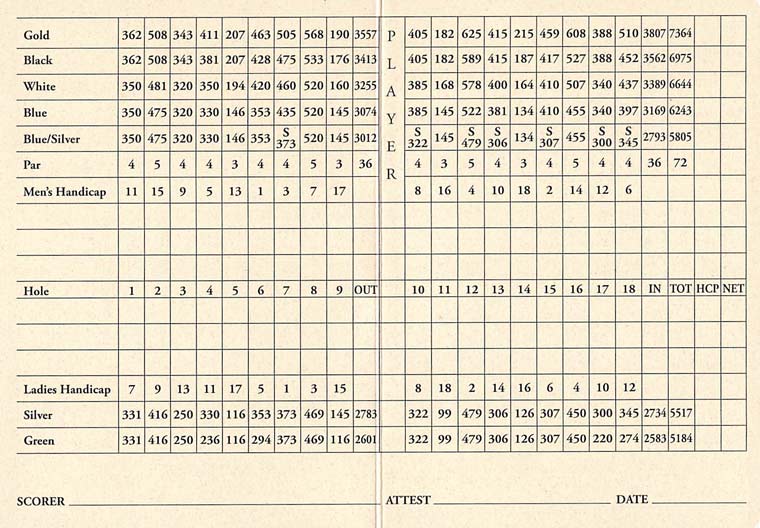

A historic restoration included improved fairway lines, bunkers that are once again in scale and position, and green expansions that brought back hole locations which influence strategy from the tees all the way to the greens. Flynn designed elasticity into his golf courses where feasible. The extensive 240-acre property the Club sits on allowed Flynn to leave room to extend tees. The course opened to a yardage of 6,531 yards, par 72. Today, the course plays to 7,364 yards, an increase of 833 yards, or a 13% increase. Firm and fast maintenance practices provide playability conditions as envisioned by Flynn so that shot shape and trajectory remain a requirement for optimal shot placement and scoring.

15. What about the course that Flynn designed stands the test of time so well that a renovation wasn’t required to keep the course relevant to today’s game?

Playing angles off the tee and on approach shots enhances the need for strategic decision making. Flynn’s greens rely more on tilt and interplays of long slopes rather than internal contouring. These greens take a considerable amount of time to get comfortable with. The bunkers have contoured bases. Flat bottom bunkers provide a singular stance and recovery demand. Contoured bunker floors, like contoured fairways, offer a variety of stances and shot demands. The routing provides changes in compass orientation throughout the round making the impact of wind highly variable. There are a number of risk/reward decisions to be made throughout the round making the course equally interesting for both stroke and match play tournaments.

16. What, if any, architectural changes were made to address the impact of the modern game?

Flynn, perhaps more than any other Golden Age golf architect, anticipated the evolution of golf clubs and balls having witnessed the impact of steel shafts and the Haskell ball (invented by a Country Club member). He took care to design his courses where possible so they could be lengthened as needed over time. In addition to lengthening the eighteenth hole at the green end, some bunkers were moved to accommodate distance increases. Shorter tees were also added to provide a better playing experience for that often-overlooked member segment.

Hole 2: The right fairway bunker was restored in size and moved downrange approximately 50 yards from its original location. The removal of seven oak trees on the corner of the dogleg allowed long hitters to carry the corner of the dogleg and provide an opening for tee shots that end up in the right rough.

Hole 4: Two new tees were built, one to add 30 yards to the hole and a new forward tee that shortens the hole by 65 yards.

Hole 6: A new back tee was added, extending the hole by 20 yards. A new forward tee was added shortening the hole by 55 yards.

Hole 8: The left greenside bunker was planned by Billy Burke in the mid-1930s. It was removed to incentivize long hitters to approach the green in two shots and to allow shorter hitters the ability to run the ball onto the green on their second or third shots, depending upon which tee they play from.

Hole 9: A new forward tee was added reducing the hole length by 15 yards.

Hole 10: A new back tee was added lengthening the hole by 15 yards.

Hole 12: A new back tee was added to the right of the existing tee, lengthening the hole by 25 yards. A new middle tee was added to the right of the existing tee. Both tees were built on the natural grade.

Hole 13: The existing back tee was removed, and a new back tee was shifted to the left adding 15 yards. The existing forward tee was removed, and a new forward tee was also shifted left while reducing the hole length by 15 yards. The four left fairway bunkers not planned by William Flynn were removed and a single 40+ yard long bunker was restored according to the Flynn plan and shifted downrange to account for the modern game.

Hole 16: New middle and back tees were constructed adding tee length to both. The second right fairway bunker was moved 35 yards downrange to influence play for long hitters.

Hole 17: The middle tee was rebuilt and enlarged, adding 10 yards to the back of the tee and 10 yards to the front of the tee. Trees at the left rear of the green were removed to reduce the distance perspective. The rear bunker was removed to enhance the penalty of a missed approach shot to the left.

Hole 18: The middle tee was moved forward 15 yards and a new forward tee added downrange near the crossing stream to accommodate the lengthening of the hole at the green end. The green was lasered and replicated in the area of the former practice green. The hole was extended from a maximum of 445 yards to 510 yards, creating a demanding finishing hole, a typical trait at William Flynn courses. From the forward tee, the hole plays a full 60 yards shorter.

Overall, the course can be played nearly 200 yards shorter at 5,184 yards. The championship tees are nearly 300 yards longer than before at a total distance of 7,364 yards.

17. Besides Gil Hanse, which members of his team worked on the project?

Both Gil Hanse and his design partner, Jim Wagner, worked on the project. Lead shapers included Josh McFadden at the outset, then Kye Goalby, and Matt Smallwood. NMP Golf Construction Company out of Williston, VT provided a full range of construction services.

18. So, would you say that The Country Club remains predominantly a William Flynn design?

The entire team had a shared restoration philosophy, and that was to restore specifically what Flynn did at The Country Club. When you have a dedicated membership and an architect team as talented as Hanse Golf Course Design that respects the excellence and relevance of the original design and is not inclined to put their own stamp on the golf course, the result is an accurate historical restoration.

There are so few William Flynn golf courses still in existence, so it is reassuring to know that one of Flynn’s finest designs will be enjoyed as intended by members and their guests for decades to come.

19. What else, if anything, do you have going on regarding William Flynn?

After many years, two young gentlemen in Virginia, John Donohue and Varun Yerramsetti, convinced me to start our William Flynn project and we are launching it this month. I hesitated to do so in the past, but these guys convinced me that we could do something unique and important beyond what typical golf architect societies provide their members.

The project has three components. The William Flynn Society will be an online repository for the William Flynn collection of architectural plans – hole drawings and routing maps, historic and serial ground and aerial photographs, and the writings of William Flynn. We will have apparel for purchase designed by C3 Brands (Bobby Jones and Sunice), accessories by Winston Collection, and hats by Imperial. We will hold semi-annual golf tournaments at different Flynn clubs. The William Flynn Institute is our entity tasked with developing a software and data science package (FlynnFactor) with applications in golf course design, restoration, and maintenance (Scott Anderson of Huntingdon Valley CC is on board) as well as other non-golf applications. Varun and John can talk about this effort in depth if that is of interest. We will also develop podcasts and articles for distribution. Dues paying members will have access to archival materials, media presentations, and The Nature Faker book on William Flynn. Lastly, we are starting the William Flynn Foundation. We have two of the three interns already involved in developing programs involved in data science, community outreach, education, and scholarships. The foundation will also organize an annual adaptive golf tournament – one of our interns played in the inaugural and second USGA Adaptive Opens.

2023 Scorecard