Feature Interview with Tom Clark

March, 2020

A life in golf: Tom Clark at his desk in the 1970s …

… and in China at Jade Dragon this century.

1. How did you become interested in golf and golf course architecture?

My interest in golf architecture really developed during my teens when I was introduced to the game by both parents and began play on local par 3 and regulation courses in the west Philadelphia area. I had a propensity for remembering hole designs I liked and those I didn’t. We used to sneak on Merion’s West Course and play a 3-hole loop until run off by the grounds crew. We played 54 holes a day at a Dupont course near Wilmington Delaware and an occasional invitation from my girlfriend’s father to join him at Aronimink Golf Club and my cousin’s invitation to Huntington Valley. I didn’t know at the time that Rolling Green was just a few miles from house until I was invited up for a consultation visit after I was an established golf architect.

2. While at Penn State, you met Geoffrey Cornish. Tell us how that encounter impacted your direction.

The real beginning occurred in my last semester of landscape architecture at Penn State when Jeff Cornish and Bill Robinson were invited as guest lecturers on how to integrate a homesite development with a golf course. Jeff stayed only a few days, but I became friendly with Bill Robinson who used our design studio at night to knock out green designs and sketches, as well as some new routing plans. I was hooked, and asked Bill how I could get into the profession. His quote, “Tom, you’re either born into it (as a family member of a golf architect, i.e. Bobby and Rees Jones,) or you luck into it as I did”. He provided me with a copy of a magazine Golfdom, that listed all the current ASGCA members and I handcrafted letters to almost all of them. Those that responded said they would keep my resume on file and I’ve always appreciated Robert Trent Jones who hand wrote a note that a position might be opening up if I was willing to travel internationally. I assumed this position was filled by Cabell Robinson, an old friend of Rees’.

A month later, and a few weeks before graduation, my professor Lynn Miller, said that he had received a call from Ed Ault, whose only employee had left him and was looking for a “bright, young, energetic and talented designer.” I drove down to Silver Spring, Maryland for an interview two days later. While not overly impressed with my long hair and beat up Ford Falcon, he was impressed with my plans developed under the tutelage of Cornish Robinson and made me an offer for $6,000 on the spot. I informed him I hadn’t gone to school for five years for a $6,000 salary, so without hesitation he offered me $9,000 and handed me a$20 bill to cover my expenses driving home.

Driving home, I thought myself a topnotch negotiator and the $20 would keep me in food and beer for 2 weeks. The one caveat was that I had to start work the day after graduation. I complied and got a motel in Silver Spring for my first week.

3. Ed Ault was a prolific designer, especially in the mid-Atlantic region, and a tidy player to boot. He built courses that could be enjoyed by the masses, sometimes even prioritizing building over billing and collecting! How were your foundations as an architect shaped by Ault?

Day one Ed asked me to join him on a field observation visit to a new 27-hole facility he had designed near Richmond called Hermitage Country Club. We left at 5:00 AM, walked all 27 holes, and I thought to myself how great this was going to be. At day’s end he tossed me the keys, asked me to run into a nearby bar and grab a 6-pack of beer, which he proceeded to drink on the return trip. He never drove again and was chauffeured around in his new Chevy’s for the rest of his career.

Ed’s philosophy on design started and finished with his three-word mantra, “drainage, drainage, drainage”. Other quotes included, “I don’t want to move more than a teaspoon full of dirt” and the most famous, “I don’t care how my courses are rated or ranked, but there are 40 million golfers each year enjoying the fruits of my labor.” The average cost of a course at Edmund B. Ault LTD in 1971 was between $300,000 and $350,000 and included a single row manual irrigation system, no sand in the bunkers, no sod, no cart paths and minimal pipe. Greens were sometimes developed with approved sand and a decayed sawdust Rototilled into the profile. His average fee for a new course was between $6,000 and $8,000. Needless to say, my foundation was one of “minimalism” before it was ever popular.

Ed Ault

4. You have 20+ designs in Arkansas dating back to the 1980s with Diamante recognized for years as the state’s best. These designs are closely associated with Cooper Communities, a development company that insisted on including recreational amenities like golf in its residential projects. Please speak to that long relationship.

My introduction to the state of Arkansas occurred with a most interesting story of a breakfast meeting with John A. Cooper and another couple at a Holiday Inn in Arkansas. Mr. Cooper had begun in the development business by purchasing large tracts of timberland from Weyerhaeuser. Mr. Ault had completed one course at Cherokee Village, Bella Vista Village, and Hot Springs Village. Mr. Cooper announced he was expanding not only at Bella Vista and Hot Springs, but purchasing new tracts in Tennessee, which became Tellico Village (3 courses), new tracts in South Carolina, which became Savannah Lakes Village (2 courses), Branson Missouri, Ledgestone (2 courses) and finally, Raymore, Missouri, Creekmoor (1 course). And by the way, that other couple at the breakfast table was none other than Sam and Helen Walton, pre-Walmart.

Ed made it clear that I would be handling most of the travel in the future and I had an amazing run of developing 24 courses for Cooper Communities. My work in the two Arkansas projects totaled 14 courses and then by word of mouth I picked up Mountain Ranch, Fairfield Bay, Thunder Bayou, Blytheville, Big Creek Mountain Home, the remodeling of Rebseman for the city, the Jack Stephens Youth Golf Academy, where I met Mr. Stephen, and the Country Club at Little Rock twice, where I met Bill Clinton.

Big Creek

5. A breakout design for Ault/Clark was TPC Avenel. Please share with us the 1983 phone call Dean Beman made to Ault offering him the job.

The development of TPC Avenel was both a blessing and a curse.

What few people realize is that before the firm was Ault, Clark and Associates, it was Ault, Beman and Associates. Dean Beman brought to the table three high profile projects, one of which was on the banks of the Chesapeake Bay just below the Bay Bridge, with holes boldly routed on the banks which could have been our Pebble Beach. Alas, when Dean became Tour Commissioner, he had to dissolve all his outside interests. That did not stop him from engaging us to remodel tour venues throughout the U.S., which included the Bardmoor Resort, Pleasant Valley and the original Sawgrass, which held the Tournament Players championship for several years. The tour agronomist at the time, Alan MacCurrach, used to be the superintendent at Chevy Chase and Columbia Country Clubs in D.C. and he recommended our firm at some other tour venues to help strengthen them. We did work at El Dorado in Palm Springs, rebuilt Arizona Country Club in its entirety and Hamilton Golf and Country Club in Ancaster, Ontario where I became the consulting architect for 25 years and 3 Canadian Opens.

Based on Ed Ault’s recommendation for the TPC to build, own and operate their own courses and create “stadium golf”, we were sent to many other sites to evaluate topography, infrastructure, etc. We went to Las Vegas, San Antonio, and the most famous one was right across the A1A from Sawgrass, now the TPC Stadium Course. Ed was most disappointed when Pete Dye was selected. A few years later Dean called and said it looked like the project we had previously worked on with him was going to be a new TPC at Avenel in Potomac, Maryland. I’ll never forget the call when Eddie summoned both Brian and I over to his desk where he had written down a $30,000 design fee and said, “I’ll see what the boys think.” We countered with $100,000 and Ed said to Dean, “Looks like it’ll be about $60,000” and thus began our work.

I became the project architect for the firm and designed and bid the work. The site was cleared, rough graded and feature work was begun when Dean visited and opted to add a “Pete Dye disciple” to the team. Greens were downsized, contours were enhanced and pot bunkers were the flavor of the day. Quite a bit of the grading was not completed due to costs, and the PGA tour opted to sprig the Zoysia versus sod. The course had a banner opening with the 1986 Chrysler Cup featuring the true legends of golf where Arnold Palmer had back-to-back hole in ones on our par 3 third hole. Not a negative comment was uttered.

The following year the Kemper Open moved to Avenel and Greg Norman infamously bashed our par 3 ninth hole, saying “they ought to blow this whole place up”. Tom Kite either birdied or parred the hole for four days and ultimately won the tournament. What Norman was referring to was that the 9th hole did not feature a good drop area, but his negative comments made a lasting impression and along with the unfavorable time slot, kept many of the big names from attending.

6. Ed passed away in 1989 and his son, Brian, became your partner at Ault/Clark. Are there misconceptions about your firm that you would like to set straight?

The biggest misconception was when we restructured and renamed the company Ault, Clark and Associates, it probably should have been Ault, Clark and Ault, because Brian has always been an equal partner. Brian and I have always remained best of friends, and we initially shared the work load on each project where I would work on the routings, grading, and green concepts with Brian’s assistance and his forte, aside from design, was specifications, bidding, etc. We then started more and more separating projects as individuals where I did a lot of the new course work and Brian tended to enjoy the remodeling projects. As the firm expanded, we would assign project architects for each new job, oversee the plans and go on a majority of the observation visits. This included our first hire, Bill Love, then Dan Schlegel, then Kevin Atkinson and finally Jim Cervone, all of whom now have opened their own practice.

Today, Ault/Clark exists in name only as Brian and I have had our own LLCs for the past 17 years.

7. Both Brian Ault and you are past presidents of the ASGCA. Can you give us insight on the challenges, accomplishments and rewards of serving as the society’s president in 1991/1992?

It was a great honor to be named to the executive committee of our professional organization, the ASGCA, and I was fortunate to serve with Pete Dye, Robert Trent Jones III, and Arthur Hills. I believe I was the second youngest president behind Rees Jones and was full of enthusiasm. Just as you get to know all of the players in the other organizations and begin to make meaningful contributions, your one-year term expires. I did manage to pilot the Environmental Guide to Golf as my term coincided with the beginning of the environmental movement and its effect on golf courses throughout the world.

The whole timing of golf development changed during this period as Agencies fought for control as an oversight committee, thus requiring as many as a dozen permits per project. Acquiring accurate base mapping with wetland delineations, buffers, endangered species, archaeological concerns, etc. could take a year before you could even route a new course and another year in permitting after your plans and specifications were completed. I think we all now have a clear understanding of what is required and the timeline associated and additional costs that are a byproduct.

Our message is loud and clear that we are “stewards of the environment” and not destroyers, but there are still the non-believers.

8. As you note, environmental issues were a focus of the society during you tenure. What were some issues that you tackled at the time?

In the beginning of my tenure, the firm was not only designing and building courses inexpensively, but it had a lot to do with the quality of the construction company who was “low bidder”. Mr. Ault favored the “Jake-leg” contractors who were small, thus offering the cheapest prices. You had to work hard as an architect to get their best efforts as they were constantly looking for ways to cut corners and cheapen your efforts.

I will never forget my first project where I had Wadsworth Construction work on a course, I was developing in Laughlin NV called Emerald River and how much easier they made my job. After the course opened, I received a call from Ron Whitten telling me he thought that course would win the best new in its category, but he had one more course to review that the raters were lauding over, which happened to be Steve Wynn’s Shadow Creek Course in Las Vegas.

Wadsworth and Landscapes went on to develop many more courses with me over the years, which have all ranked high in “best new” or “best in state”, but a lot of the work I am most proud of is when I hooked up with some relatively unknown firms at the time, such as TDI, Sajo, Mid America and United Golf who have all gone on to become bigger firms and excellent contractors. Make no mistake, in this industry the construction firm can make or break the architect and there are many architects whose reputation is more a byproduct of the contractor and most of all their skilled shapers.

9. Magnolia Green Golf Club south of Richmond features some of the boldest features (from centerline bunkering to interior green contours) in the Mid-Atlantic region. Tell us how you came to partner with the Nicklaus organization on it.

Every golf course has a story and Magnolia Green GC in Richmond is no exception. I had completed the routing, strategy, clearing and grading plans and had bid the project when the owners opted to add a “name tour player”. I first met with Lanny Wadkins, who they were ready to sign up until he was fired from the broadcast booth. Subsequently a search began for other options and they went for Nicklaus Design. The initial developer went bankrupt but we convinced the lender to complete the 10 holes that were all ready for seeding and sprigs. Three more contractors and five years later the remaining eight holes and practice facilities were completed.

The course was originally going to be Bentgrass tees, fairways and greens, hence the extra wide clearing and the 400-foot playing corridors that gave us the width for central hazards. The objective was to create a look unlike any of the other area courses with fescue ringed gnarly bunkering and some interior tall native areas that were out of play. The development itself has for years been one of the fastest growing on the entire east coast and the course continues to prosper. Many of the members are fiercely loyal to our design, even though it can play quite tough.

The 12th hole at Magnolia Green is capped off my a green with a pronounced left to right tilt.

10. Talk about some of those greens like the 10th, 11th, 12th and 16th.

I first met with one of their lead designers, Tom Pearson, who reviewed the site and plans, but before he even started, he was transferred to Belgium to oversee Jack’s European work. Their next designer was a great guy and we were very like-minded until I asked what they intended to contribute to the design. Up until this point my green designs were only conceptional. A week later I received a packet of 8 ½” X 11” green plans and off we went. I either flipped over, or completely redrew about half and added contouring to the bunkers as there was none. I was informed that Jack’s current philosophy was bold contours with a break or accent point every 20 feet. It created a lot of un-pinable areas that we eventually modified on the outside of the putting surfaces. Learning how to attack some the tougher hole locations only comes with time and it gives the members a distinct advantage over their guests.

Putting off the front front of the 11th green at Magnolia Green is a distinct possibility.

11. What constitutes great architecture?

First, let me point out that Great Design and Great Maintenance often get confused. Many of the larger design firms employ agronomist to insure the best possible presentation of their creations once complete. We are reliant on the golf course superintendent to complement our design and I continue to stay involved not just for that purpose but to also help rectify any “mistakes” that may have ensued during construction and grow in. An architect should continue to revisit his or her projects through the years as you will be amazed at the compliments or complaints of the players or members.

The real fun of course design is showing the adaptability time and time again to produce a product with which everyone is happy. Try your skills in the mountains of Korea or West Virginia and see what you come up with (especially when your owner cuts the construction budget by 2m on a 5m bid!). Each site is unique but throw in working with different cultures and different owners and you are guaranteed that the experience will be both interesting and challenging.

Take a dead flat site and mold it into a roly-poly 27 hole complex known as Magnolia Creek in League City Texas or be forced to receive 3 million cubic yards of fill on another flat site in Newport News, Va known as Kiln Creek and make the course visible to homes that are 30 feet below the fairways!

For many architects, you have to learn to build a course so you won’t notice the hundreds of surrounding home sites.

Or try completing a course for under 3m for that is all the owner has budgeted.

Again, great design is all about adaptability and one of the best was Pete Dye. Pete’s TPC at Sawgrass (we actually got first crack at that site which was dead flat) vs The Pete Dye Club in WV (we also got first crack at that site with Jim LaRosa) – the fact the man pulled off both highlights both his genius and adaptability!

Some architects complain that their competitors get all the “great sites”. I say, “They earned it.”

12. Your latest effort, Cutalong, is located near Lake Anna in Virginia. The project has been off and on for 20 years but it looks like late fall 2020 will be when it finally opens. Tell us about it.

As I said earlier, every course has its own story and none more than Cutalong on Lake Anna, Louisa, Virginia. I have managed to survive four different owners, four environmental firms, countless engineers and numerous golf contractors and we now have a stable developer (Stillwater) with ample resources. When the project began in 1999, I envisioned creating a spin-off of the National Golf Links on Long Island, which I felt then and still do, one of the most fun courses I’ve ever played. With all the new courses being developed back then, I felt I needed a “hook” to draw from Washington D.C., Richmond, Charlottesville, and Fredericksburg.

13. You collaborated with Ron Whitten, a walking encyclopedia of knowledge, at Cutalong. How did you swap ideas back and forth about which what design features to borrow from where?

After the first developer, and after the course was pared from 27 to 18 holes, I enlisted Ron Whitten to collaborate and utilize his vast knowledge of old and new designs that we could intermix on each hole. Nothing in architecture remains cast in stone. We have added tributes to famous designers such as McKenzie, Colt, Jones and Dye and a sprinkling of Civil War fortresses. We completed 11 holes and the practice facilities last year and hope to finish the remaining 7 by spring of this year. In fact, we are still making tweaks and improvements, which is the luxury that time gives you.

The Biarritz green at Cutalong is approached from an angle.

14. Whet people’s appetites – what are a few of your favorite holes/features at Cutalong?

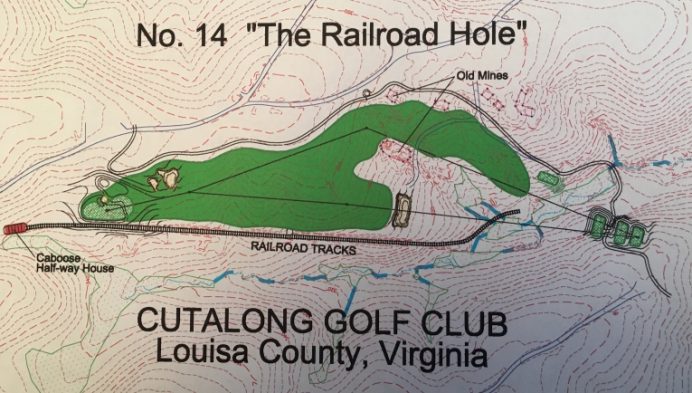

We have a “Pebble Beach” 17th green fronted by the MacKenzie bunker on No. 10 at Augusta as well as a Punchbowl green at the 15th, a Redan par 4 and our soon to be infamous railroad hole, which parallels the abandoned railroad from the site’s mining era. Our 17th emulates MacKenzie’s famous Gibraltar hole which I personally went to Moortown in England to play and photograph on a “study tour” pitting the European, Australian, and American Societies of golf architects in a friendly competition.

The split 15th fairway under construction culminates at a Punchbowl green.

The sodded 15th fairway beds down for the 2020 winter.

15. You mentioned National Golf Links of America. Talk to us more about your impressions from there.

The National Golf Links is not just one memorable hole, but a collection that flows from one exceptional experience to the next. As any great course, it takes you on a journey of all the site has to offer with its rolling topography, captivating views, a smattering of water features and a sandy base. It features some of the most innovative bunkering and greens on the planet and when you add it all together, it is just plain fun to play.

16. How about a favorite hole that you have designed? Please describe it and what you like so much about it.

As with any architect’s design career, he or she hopes to be constantly improving on their last efforts so I’ll select a hole from Cutalong, which will be the 14th or the “railroad” hole, so named as a spin-off from the famous road hole at St Andrews. It was originally routed paralleling an abandoned rail line from its mining era that delivered ore carts for processing. It evolved into a split fairway when I discovered that there were four vertical mine shafts off to the right of the proposed hole. Knowing the developer could not use this area for home sites, I incorporated it into the hole. The shafts extend down over 300 feet and were capped and each has a basin to make sure water doesn’t find its way back down.

In general, I am not a big fan of split fairways as inevitably, one route is preferable and more comfortable than the other. In this case, the left side offers the player the opportunity to get home in two but is fraught with danger. From the narrow corridor of the trees, to the wetland carry, to the gnarly rough, to the three perpendicular bunkers and the “railroad” bunker on the left, the tee shot (which is only available for those playing the blue or black tees) is a true risk reward proposition.

The right side is wide open and much more friendly but will definitely make the par 5 a 3-shotter. The green is a boomerang paralleling the extension of the “railroad” bunker on the left. It affords the golfer an opportunity, if he hits the front of the green, to actually putt to the back-right corner by caroming off the severe slope on the green’s left side. Of course, there is the road hole bunker lined with railroad ties on the right.

17. What do you hope your legacy will be? Why should someone hire Tom Clark today?

The legacy question is a good one as the most overlooked and often unspoken contribution is cost, unless the designer’s fee or cost of construction is simply outrageous. Aside from some of my par 3 courses, I only know of two that have closed and those were strictly for development reasons . . . .

Having almost 50 years of experience, having seen and done numerous innovations in over 100 new courses and an equal number of remodeling efforts, I am constantly evolving to implement good sound design practices and meet the client’s objectives at significant cost savings and value in both design and construction, which reflects on the bottom line moving forward. I bring that experience to each and every project.

18. The next generation of golf course architects faces an uncertain future, to say the least. As a wily veteran who has seen plenty of economic boom and bust cycles, what encouragements, pitfalls to avoid and recommendations would you have for young architects?

It was unfortunate that the last downward cycle seemed to start in the early 2000s where many large firms like my own, released almost all their young talented designers due to lack of work. It can be said that once you have the taste of design and construction in your blood it never leaves. Some managed to flourish, but the competition and availability of opportunities made it difficult to prosper. Some sought other means of employment while keeping golf design as an option in order to keep their families fed. This has by far been the longest downturn I have personally experienced, but I am actually seeing some light on the horizon.

My advice would be to hang tough and definitely don’t get too cocky because you’ve had success on one project. You have to continually improve and diversify in today’s market. Most of all if an opportunity presents itself, encourage your shapers and superintendents to get the best product possible and one day you may just find that a wealthy country singer, professional athlete, golf developer or builder selects you.

In other words, create your own luck.

The End