Feature Interview with Todd Eckenrode (Part 2)

May, 2018

Is there more activity in restorations and renovations than new course designs these days?

The bulk of our work is in restorations and renovations of courses of the Golden Era of Golf Design. Though we love new course design, those opportunities in the last ten years or so are few and far between. We feel very fortunate to have completed the new courses we have of late but working on courses of this older era is of immense interest and brings genuine enjoyment. As mentioned in my April Interview, this began with the love and impact of Pasatiempo on me, and the respect and value I place in those courses continues to this day. It’s an honor to be consulted and work with these courses and we take their value in the game quite seriously.

We also greatly enjoy working on courses of a more modern era where we think we can produce significant improvements through renovation or re-design.

What is the basis for restoration work?

Research is the basis, without a doubt. Luckily, the fascination with the origins and history of these clubs has taken off dramatically in the last decade or two. Oftentimes, most or all of the research is pretty complete, really. I’ve run into this recently at a Club where I looked into all of our typical sources, and the Club had already done the same, there was really nowhere else I could think to look. Other clubs have surprisingly little information, and that’s where we have to dive in.

Tom Naccarato is a valued friend and resource for me, both because of his indepth knowledge, but also with both of us being from California (and the bulk of our work in this regard being in California). If he doesn’t already have the aerials, or ground photos, or newspaper clippings, he knows where to look, and has been an immense help many times over. Tommy is not just a resource, his combination of knowledge and passion is unsurpassed in my opinion.

I have truly enjoyed the times where I’ve been able to lock myself in the club’s history room, or collection of archives, though, and can just spend the time going through what they have myself. It’s fascinating, reading the “minutes” from the 1920’s, for example, and the early marketing pieces when the courses were new. Orinda and Lakeside come to mind in this regard. I spent a day and a half in the archive collections room at Orinda when we first started there, and found some great information on the club and course itself, but also interesting correspondence with Cypress Point and other peer clubs that was fascinating.

Tell us about the recent work at Max Behr’s Lakeside Golf Club.

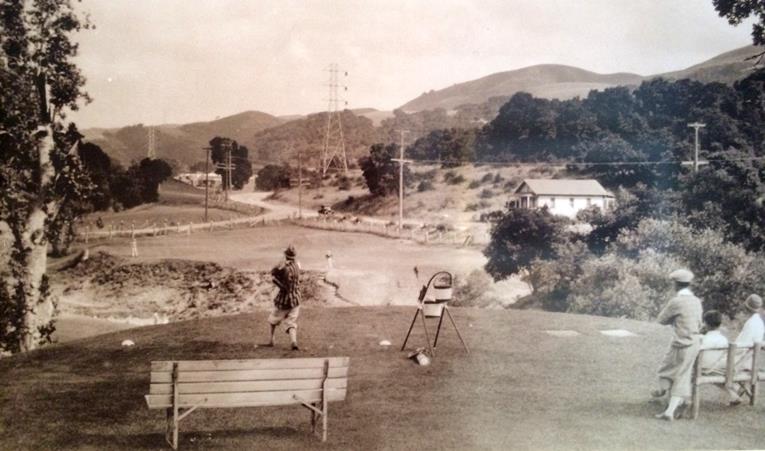

At Lakeside Golf Club, established in 1924 but opened for play in 1925, it was green perimeter restoration, bunker locations, holes like the short par-3 15th, and a general feeling of more openness and exposure to the great contours of the course that we strove to restore. The greens had shrunk into tiny semblances of themselves, but the lost perimeters weren’t hard to see in the ground. Though we were limited in how much could be restored, based on available Poa sod, we did recapture over 20,000 sq. ft., which proved very significant. Bunkering was largely restored in location based on the old aerials, but the style of flashed sand and naturally wavy lines was not literal. Otherwise, fairways and short-cut areas around greens have been expanded greatly since we’ve started consulting here, and many hundreds of trees removed as well, opening up the vistas and a feeling of place.

A great characteristic example is the par-3 3rd hole. A moderate length hole, tree plantings had closed in and isolated it from the nearby 2nd hole and distant views. The tall pine behind had replaced an original back bunker. And the bunkering left and right had become overly built up. In the original aerials, the left bunker was actually the bold, larger scaled bunker, with the right bunker a smaller scale and set into the slope. The bunkering was restored to this characteristic, with the back bunker returned to play, and with the green roughly doubling in size, this restored the outer “wing” hole locations set up against or behind the new front bunkering. All trees but one on the right were removed, as well as numerous taller trees behind to bring back the wider and longer views.

The most fun hole to work on was undoubtedly the short par-3 15th. This was an original hole (though the 9’s were reversed from today’s numbering). There is an adjacent longer par-3 15th that the members play as well, but that was added in the 1960’s or 70’s, I believe. That only goes to show how much the value in this short par-3 had eroded over the years.

The original hole was such a standout, about 90 yards in length and originally surrounded by bunkers. When we first started consulting here over a decade ago, there was so little regard for the hole that a 40’ Cypress tree was in front of the green, rendering the hole unplayable from the original tee area! Needless to say, we had that removed, and with this last project, were able to restore the greenside bunkering to its original concept of surrounding the green. Modifications in the flash of the sand, and breaking up one bunker into two, for example, to provide grass walk-ups for the golfers are not literal, but the idea is there and the drama and thrill of the hole is back. The green had shrunk into a tiny circle, but the “wing” hole locations that made the hole so interesting were there in the ground (or rough).

The green was originally very wide, but shallow. There was one “backstop” to play to if you needed such to stop your ball, which we restored as well. This is such a fun hole to play now, and the members feel this way as well. It was a feature of their first big invitational since re-opening, where they played the “short” 15th over the “long” 15th two out of the three days, and in the Derby as well. I’m so happy with how this turned out and that it’s truly one of the best and most fun holes at Lakeside once again.

There was so much more at Lakeside that was accomplished that is significant, especially about the ground contours. Lakeside’s fairway contours are some of the best in all of California, and we did all we could to showcase these by widening fairways, removing the tree-lined look that had evolved there, and oftentimes joining fairways as well. Holes like the long par-5 5th hole, which used to play across the once natural LA River, but was moved across to the north side of the river long ago, has some of the most dramatic, rolling contouring to be seen.

When you play Lakeside now, you no longer feel constrained, you are much more aware of this unique land Behr created, even if the faux-dunes and old riverbank cannot be restored, both for their own reasons, philosophically and physically. It’s a wonderfully special course, very different than LACC, Riviera or Bel Air, and I’m so glad for this. Nonetheless, its quality is comparable with these clubs in every sense, in my opinion.

Shapers included Jonathon Reisetter on his farewell before going back to school, Andrew Littlefield, and some late relief work from Blake Conant on the last few holes. Robert Hertzing is superintendent, and it could be argued that this is the best presented golf course in California. Those old Poa greens are as good as they get.

Very neat, hopefully Max Behr will start to get more credit than just for his writings. Moving on, describe the variety of holes on William Watson’s Orinda CC in Northern California and your work there.

Orinda CC was opened in 1924 and designed by William Watson. Watson is best known for his work at Minikahda, Belvedere and Interlachen in the Midwest but over the past decade, it has come to light that he completed numerous fantastic layouts throughout the Golden State too. To the south, you have San Diego CC, La Jolla CC, early San Gabriel CC, Hacienda CC, the original Virginia CC, and Hillcrest CC to name a few. In the north, besides Orinda, he completed a redesign of the original Jack Neville course at Diablo CC, where we also consult, that is a fantastic layout. And of course his design at The Olympic Club.

At Orinda, there are so many unique holes, which is why the routing and original design is a cut above, in my opinion. The 1st hole, with a ridgetop drive, leading to a blind short 2nd shot, though I wouldn’t characterize as one of the standout holes, is nonetheless a preview of what’s to come on a quirky and sometimes hilly layout. The 5th, named Mousetrap, is a moderate length par-4, featuring a drive across a creek and valley, to a side-sloped fairway, then an uphill approach to a reversed boomerang green. The green wraps around a prominent ridge off the back slope, bisecting the left and right sides quite strongly.

The 8th, named Deadhorse, is a fantastic drop-shot par-3 of originally 123 yards. Poorly advised redwoods had been planted behind the green, which were controversial to remove until the view beyond was exposed. Otherwise, we rebuilt the green to remove much of the sand buildup that had occurred over time, making it just too small and crowned. The bunkering is restored, and bunkers that had been added to the left and rear were removed, with short-cut surrounds replacing them. This provides the golfer the ability to play the ball up the hill in a variety of ways, but it is still quite a challenging hole if the green is missed to either side. What a beautiful but dangerous little par-3 Watson built, and it was a thrill to restore.

The green complex for the par-4 11th, named Graveyard, references perhaps an old Indian Burial ground, or perhaps simply the style of mounding reminiscent of this. The drive favors use of the strong slope from the right to sling the ball farther down the hole of this right to left dogleg. Early work involved removing most of the trees between this and the adjacent 2nd hole (which dramatically naturalized and improved the 2nd hole as much or more than the 11th). Currently, the path between the two is being removed as well, so the fairways will join, as we did between #12 and #14, and #16 and #17 to great effect.

But the real interest of the hole is in the surrounds. A hole devoid of bunkering, instead Watson employed numerous mounds to create a bowl-like effect to the green, but if missed, the short-game variety is amazing. You’ll never have the same chip or pitch here, it seems, and you can use the slopes for more direct or indirect routes to the hole. The short-cut of the surrounds stretches all the way to the tees for #2/#12 as well, and with more path removed there and the tees joined together in places, naturalizing and softening the area further.

The 14th, named San Pablo, after the adjacent San Pablo Creek to the right, is a wonderful short par-4. The original Watson design had a long fairway bunker through the dogleg, and a shorter fairway bunker on the right, which we restored in concept. Prior to the project, numerous non-native trees were removed on the right as well, trying to engage the adjacent fall-off toward the creek. The Green complex for cart path was removed through the majority of the hole on this side as well.

The green was more standard-like in the 1928 aerial, but in 1936 and ’37 letters from A.W. Tillinghast, he suggested some changes to this green, into a “long ribbon-like green to take the chipped second shot”, which is essentially the character the green was to this day. Some slight restoration to the sides, and lowering of sand build-up was all that was needed on this unique green and hole.

The 15th at Orinda, named “Despair”, is a beautiful but dangerous par-3, set hard against a creek. A bunker had been added to the left side long ago, but we removed it to re-establish the green’s close proximity to the creek edge, and also to maximize the space to the right for the “bail-out” shot, which I must admit to favoring! There is a mound set to the right of the green that we restored as well, which adds challenge and interest to chips from this right side, if you aren’t pin-high and thus need to navigate its slopes. What we couldn’t restore, however, was the great irregularity and naturalness of the creek itself. Decades ago, it had been channelized.

Shapers included George Waters, I believe his farewell project as well (makes me wonder if I force these guys into retirement), and Bret Hochstein. Bob Lapic was the superintendent when the project planning was started, but Josh Smith took over prior to construction, and is continuing to improve the course further to this day. Josh has a keen eye, and we value many of the same things in architecture how a course should play, namely firm, fast, and fun. The golf course should be presented as simply and naturally as possible, and should showcase the natural attributes of the land. I feel lucky to have worked with both of them on this great project, and in continuing to work with Josh into the future.

There have been significant small improvements every year after the project was completed, oftentimes just functional, such as to improve drainage. But other times carrying on some of the design changes we’d hoped to accomplish in the project but just weren’t able to originally, such as joining fairways on Holes #2 and #11, exposing the rock behind the green on Hole #4 (appropriately named Meteor by Watson), and other such subtleties. I’m very hopeful we can continue to improve Orinda even more, and with Josh at the helm I have little doubt this course will just get better and better and be considered in the upper echelon of Bay Area courses.

In California, natural drainage ways often times seemed to have been embraced and became a major part of the architecture.

Natural creeks, whether they be seasonally running with water, or predominately “dry creeks”, are fantastic features on a golf course. First off, they serve a very significant and needed purpose, to move storm water through the golf course efficiently. But their value as a hazard is paramount, especially if they have a level of recoverability, and they can be found on many older courses for just these reasons.

One of my favorite aspects of any project we’ve completed has been the restoration of the “barranca” or creekway at Brentwood Country Club in Los Angeles. It was designed by Watson and Macbeth originally and Behr later did some redesign work. Brentwood is a wonderful historic course, probably only a mile or two as the crow flies from Riviera CC, but not blessed with the scale or terrain of Riviera. The strongest natural feature it does have, however, is a large drainage course that runs right through the middle of it. It varies in depth from just a few feet to up to 25’ in depth, and varies in width similarly, but is not narrow by any means. The largest area is close to 100 yards wide.

While I ordinarily prefer to use such hazards diagonally, this would have only allowed two or three holes to utilize it. Instead, it was brilliantly utilized in the routing in a perpendicular, or crossing manner, and in a tremendously varied way. By routing the holes in this manner, eight of them play over it, and it’s by far the most memorable part of the play now on the course.

All of this area was in turfgrass when we started work here, but with some of the steeper areas grown out to unplayable length. We cleared all areas of the turfgrass, and removed all trees from the area that didn’t lend themselves to a native California palette. Much of the creek bottom and slopes had been smoothed due to extensive drainage work over the years, so we took to reshaping the whole area as well to recreate eroded banks, terraces, and a meandering look to the creek bottom itself, basically restoring a sense of naturalness.

Lastly, the entire area was planted with dozens of native California Oak and Sycamore, as a natural barranca in this part of the country would have. And the ground plane was grassed in drought tolerant fescues.

The effect is one of a strong and natural identity. The aesthetics are beautiful, and a great contrast to the finely manicured course. As importantly, if you hit a ball into these areas, which I certainly have, there is a measure of recoverability. Sometimes you might be lucky and have a good lie and a simple shot. Other times, not so much. A level of luck when hitting into a hazard is expected. The excitement and reward from pulling off a recovery shot is one of the most rewarding aspects of golf, however, and is alive here.

Blake Conant and Kye Goalby were the main shapers at Brentwood, and I’m very proud of the rest of the work on the course as well, with a handful of great new greens by Kye, beautiful bunkering, lots of short-cut surrounds and vast tree clearing to open up the property. There were a few other cameo appearances here, notably Tony Russell, who flew down for a few weeks to finish up the important creek work.

Very neat, a barranca certainly seems to be a major differentiator between East Coast and West Coast architecture. A prime example of its use is also found at your beloved Pasatiempo, which makes me ask: have you worked on many Dr. Alister MacKenzie courses to date?

We’ve been fortunate to consult on a few. For a long time, we’ve consulted with Green Hills CC in Millbrae, CA, which opened in 1929, designed by MacKenzie and Hunter. This course was originally called Union League Golf and Country Club. Our work has been limited, such as a rebuilt 13th green and other small tweaks. We’ve completed a Restoration Plan for the Club, however, and are very hopeful more can be accomplished in the future. The course has some absolute standout holes potentially. The 4th and 5th notably, the 11th, and the finish 14th-18th could be outstanding if restored. The 15th was one of the most dramatic par 3’s in the SF Bay Area, and restored green perimeters, tied-in to restored bunkering would make for some fantastic hole locations and thrills. MacKenzie and Hunter traits can be seen throughout quite clearly.

The par-3 15th at Green Hills CC, in recent times and as existed in 1937. Note the significantly larger scale to the bunkering and expanded green, offering numerous interesting hole locations and increased variety.

It was also a pleasure and honor to work on The Valley Club of Montecito for a 2-year project in 2013-2014 and a bit of consulting after. Tom, Jim and the Renaissance crew had done such great work there beforehand restoring most of the MacKenzie & Hunter work, so this was predominately a fairway conversion project, aimed at reducing water usage. Proper fairways lines were set out, and we tried to join up as many fairways as possible, to maximize the shorter and more drought tolerant fairway grass, and present more of a “one cut” look. This was accomplished by joining four sets of holes together that previously had rough between them. We also took this opportunity to help the club in removing as many of the non-native or non-original trees as possible, predominately various species of Pine planted over the years. When looking at old pictures, nearly all that can be seen in trees are native California Oak and Sycamore, Monterey Cypress, and Eucalyptus (a naturalized species in CA). The removals also opened up a lot of short-range views into nearby holes as well.

With the goal to reduce water use, the club also worked on converting some turf areas to drought tolerant fescues, and this naturalized some out of play areas nicely. The approaches were also reworked, to get the ball to bound in better, and a few bumps reworked as well (such as that in the approach of hole 5). A handful of original bunkers were reworked to get more in line with the old ground photos and aerials, such as the fairway bunkers on Hole 2 and 18. Our goal was to walk lightly here, and with good reason. Valley Club is as good as it gets, and if I had one course to play every day for the rest of my life, this would probably be it.

Mike McCarten was the main shaper here, with help from Andrew Littlefield as well in year 2.

Lastly on the MacKenzie front is the long-range restoration of Redlands Country Club. Redlands was originally a nine-hole course, established in 1896, featuring oil-sanded greens and dirt fairways. There is documentation of Dr. MacKenzie’s redesign, opening in 1927, with descriptions of each new or re-designed hole.

Mike Devries beat us out for this project long ago, but was kind enough to refer us in a few years back when he wasn’t available for the first phase of recent construction. We’ve studied old aerials and photos, to adapt the design to the 1927 work as best we can, and much of it is visible in the ground.

The first work, in 2016, brought about a restoration of Hole 1 and 4. Hole 1 is a fun shortish par-4 with a green perched off the hill above and a fronting left bunker. We restored green area, and worked on getting the upper hillside properly “tied in” to the green, rewarding play off the slope. Hole 4 is a ridge-top hole where play into the green is rewarded by a drive that can stay atop the crowned ridge and not fall off to either far side. We restored green surface here again, bunkering and opened up the approach again to reward the ability to bound in the ball, particularly from the preferred angle.

The second year brought about a restoration of Hole 2 and 3. These were great fun to get into, as perhaps the two best holes on the course. Hole 2 is a strong par 4, with a semi-blind drive over the crest of a hill to a broad valley. The green is what makes this hole, however, with two bowls separated by a very strong ridge down the middle. Needless to say, playing to the correct side of the green is paramount. We worked off the old aerial to restore the left bunker to a long, diagonal feature, and removed a right bunker that had been added over the years, opening up the approach on this side to the ground game.

Hole 3 is a beautifully sited reverse-redan par-3 set atop a native canyon, with a grove of old California Oaks behind. We removed all of the non-native trees that had been planted along the canyon, which took away the natural effect of the land and blocked great mountain views. But the most fun aspect of this work was the restoration of a long diagonal bunker complex running from the centerline and up to the right side of the green. We also shifted a front-left bunker that had been added, and moved it off to the side, so that the proper option of running the ball in from the left could be played. This is a natural and stunning hole now, and we are very excited for the rest of the work in the coming years. Particularly the restoration of the boomerang 17th!

Brett Hochstein was the shaper for us in the first two years here.

If you could restore any course in California, which would it be?

Pebble Beach would be the obvious answer, considering its potential, its unusual early design, and its place in the game.

On a small scale, perhaps the 9-hole Northwood Golf Club, as anything MacKenzie is of interest to me of course, and the sense of place here is extraordinary.

What lesser known architects that have practiced in California would you consider to be worth studying?

Though not unknown by any means, the work of William P. Bell, both in collaboration with George Thomas and on his own, was superb. Many of our client courses were redesigned by Bell into their most current form and this may tell you something. Virginia CC is a limited edition of sorts, representing the brief partnership of Tillinghast and Bell.

Very little was attributed to William Watson until fairly recently so I am very glad to see that is changing. Watson was quite prolific but the quality of his designs was notable and the variety in his work outstanding.

And of course, the small sample of outstanding work by Max Behr. Lakeside and Rancho Santa Fe are without a doubt his finest, and must be seen by students of golf course architecture. Victoria as well, though to be honest I don’t know this fine course well enough. Max’s influence on others cannot be undersold.

What about renovations or work to more modern courses?

Well first off, if a course is not of the Golden Era, then we are much more bound to be looking at it from a fresh perspective, on how would we have designed it from scratch, and how can we maximize the property. How can we re-envision them perhaps? Two projects that come to mind are Quail Lodge Golf Club in Carmel Valley, CA and El Niguel CC in Orange County, CA.

At Quail Lodge, we found a tired golf course at the time, originally built in the 1960’s that had not had any real significant improvements or updating since. The lodge and clubhouse had recently undergone wonderful renovations, and it really is a great property. The question became, how could we elevate the quality of the golf course by adding interesting and relevant features?

Two of the biggest negatives of the property were the fact that it was all turf essentially, so it lacked texture, depth, and visual interest. Also there were far too many water features built into the original design. This was an era where that was favored, but there was no compelling reason for it. The golf course plays along the Carmel River in many parts, a wonderful feature, and has great sandy soils that I’m sure are riverbed sands from when the river traveled a different course.

So we set off to greatly reduce the turf, particularly on the perimeters, along roads, etc. The plant palette is a mix of native and naturalized drought tolerant plants, offers a great buffer and contrast, and makes the golf course feel that it’s located in a more natural setting. This project removed over 20 acres of turf overall. The benefits to reduced water use are very relevant, and also achieved are similar reductions in inputs such as fertilizers and pesticides. Wildlife now have more habitat and the aesthetics of the golf are highlighted.

We were able to convince ownership to eliminate or reduce about half of the lakes, but not all that we had hoped. Still, the improvement in the play is substantial for those that we did remove, and none more than the par-3 17th. The previous hole was a simple par-3 set against a lake, like thousands of other similar holes. We were able to cut in a deep grass swale in lieu of the water, which wraps around the front, left and back of the green. This offers a fun hazard, well below the green surface, from which to play a recovery shot back up. It’s eminently playable and the art of recovery is alive and well. This is now my favorite hole on the course, without a doubt.

We carried on that concept of creating deep swales to create interest, variety, and strategy into other areas of the course as well. Most notable is that which was created on the front nine by carving in a deep swale left of #1, which crosses the fairway there and across #2 as well, before turning up the middle of #3 and ending past the driving zone of this hole on the left.

Otherwise, we focused on creating interesting bunkering of varied scale, and relocating them to be strategically placed. Rough used to surround every green, so we worked all green surrounds as well, and created large short-cut surrounds throughout, greatly enhancing the variety of outcomes and subsequent shots required to recover.

Shapers were Blake Conant and Jonathon Reisetter, who both created very interesting bunker forms that are probably the strongest memorable features of the course now. Ken Alperstein was the landscape architect, who we’ve collaborated with many times before on turf reduction projects.

How about your current renovation project at El Niguel CC?

We just recently broke ground on a significant renovation at this club. What attracted us to this course was it had what we felt were really good bones, including an interesting creek feature that runs between most of the holes, lending it a mid-western feel.

The initial work we were able to accomplish was a large-scale turf reduction and tree removal project. We started with a turf reduction plan of over 10 acres, and the member response was so positive that we quickly added an additional similar amount. In lieu of turf were large tree mulch zones, and drought tolerant plantings in more out of play areas. These have matured nicely, and add a beauty to the property that it lacked before, besides the benefits of sustainability noted above. Ken Alperstein was again the landscape architect on the turf reduction project.

We’ve just begun the next phase of the renovation work, but started strong with a new green and green complex for the outermost par-3, the 14th. This is a drop shot hole, and we created a small green, defending strongly in front-left with a beautifully shaped bunker, and short-cut fall off surrounds in the front and right side as well.

We intend to shift as many holes toward the creek as possible, and the work in this regard started this past winter, with tree removals in these zones. Many of the creekside holes had 30-40 yards of rough and trees between the fairways and the creek, completely detaching them from this feature. With the removals, and starting to mow the fairways out, we can now shift the fairway bunkering or other fairway features in a way to integrate the holes with the creek more directly, and utilize the hazard strategically. I’m really looking forward to getting into many of the front nine holes in this regard.

The more I work on this project, the more excited I get. This can be a fantastic club to be a member when all is said and done. It’s not pretentious, or trying to be something it isn’t. It’s going to be a course that’s really fun to play and now worthy of its beautiful setting.

Shapers are Blake Conant initially, with Kye Goalby flying in for middle relief soon, and Pete Zarlengo in from New Zealand for the duration. So we certainly have the talent, and I am very thankful for that this summer.

Lastly, what is in the future for Todd Eckenrode-Origins Golf Design?

We continue to consult at Palos Verdes Golf Club (Thomas/Bell Sr.), San Gabriel CC (Macbeth/Watson/Bell Sr.) and Virginia CC (Watson/Tillinghast/Bell Sr.), all wonderful and historic courses, in addition to the courses mentioned above. We are involved in Master Plans for a number of other courses as well. I’d be lying if I didn’t say we are most excited, however, for the opening of the Twin Dolphin Golf Club in Los Cabos, later this fall. In fact, Andy and I are heading down there this week to finish up the greens with Cliff and get the last details just right. Looking forward to seeing this exciting project grow-in and putting a peg in the ground in the future. Actually I look forward to seeing Freddie Couples put a peg in the ground more, and maybe I’ll loop!