Feature Interview

with

Todd Eckenrode

April 2018

How were you introduced to the game and architecture?

It’s interesting with all of the focus of late on par-3 or “short” golf courses that this was how I started in the game as well. My dad started me in lessons, around the age of 12 and I remember my early rounds on the course there, playing with him and assorted old-timers and just loving it. I also fondly remember “moving up” to an executive course, which was mostly par-3’s but had a few “big” holes, which were probably short par-4’s, but didn’t seem so at the time! So for me, it really was a progression onto courses larger and larger.

After a year or so, this meant my jump to the first full course I’d played, which is called Spring Hill Golf Course, in a very rural part of south Santa Cruz County, California. I was 13 or 14 years old at the time and I was pretty hooked on golf. Summer came around, and luckily I had a buddy who lived nearby interested as well, so our parents would drop us off at Spring Hills in the morning and pick us up at the end of the day. The Junior Golf rates were $5, I recall, which was all-you-can-play golf, with a hot dog and a coke at the turn. What a deal! We played 36 holes practically every day, and I remember that was the first summer I broke 90, then soon after broke 80, and that was it! I was all-in at that point.

The course was lovingly called a “farm” course, I recall, which was respective of its setting, and it had a mid-western feel to it. There was agriculture around it, and the conditions were probably not perfect, but it was a fun golf course, and laid on the land naturally.

As I moved on to play in high school, I began working and playing out of Pasatiempo Golf Club, and what a move that was. I remember realizing that this was a special golf course, but of course had no idea why. There was knowledge and slight promotion of the MacKenzie history there. But this was all before the discovery of the amazing Julian Graham photos by Bob Beck, and of course the great restoration of the course by Tom and Jim and their talented guys in the field. Needless to say, Pasatiempo would influence me greatly, mostly in ways unknown at the time.

Pasatiempo’s 1st and 9th holes originally, reminds one of The Old Course in some ways. Courtesy of Pasatiempo Golf Club.

I went on to play in college, walking on at the University of Arizona, where I played for two years, but never traveled to tournaments. It was a great experience of playing with tremendous players, though, including the reigning U.S. Am champion at the time. There was crazy talent there. But the writing was certainly on the wall that I was not going to travel, so I transferred to U.C. Santa Barbara, and what a move that turned out to be.

My coach for my last two years there, Walter “Topper” Owen, was an incredible man and teacher in life as much as golf. He was as much concerned with the experience we would get from this great moment in our lives as in the quality of golf we could play. We studied the mental side of the game, we had morning Yoga classes, and of course it didn’t hurt practicing weekly on The Valley Club as well.

Instead of playing the monotonous schedule of the Big West conference, in a van up and down California predominately, we traveled extensively to play in Hawaii, Utah, New Mexico, and other great locales and a smattering of standout courses, such as Yale. BYU also hosted a tournament in Guadalajara, Mexico, and Augusta College hosted one the weekend before the Masters, giving out practice round tickets to the teams for the days after. The statewide tournaments we retained included the historic Western Intercollegiate at Pasatiempo, and USF’s tournament at The Olympic Club. As I was beginning to ponder a future in golf course design, I soaked up the moments at some of these wonderful courses, with an eye to the future. But most importantly, what an experience I had, all attributed to Topper, and we remain close friends to this day.

Intermixed in all of this, my deep family tree all had roots in Ohio, where we would take yearly summer trips. This was my introduction to Donald Ross, where he had numerous courses in the area we’d play with my Dad and Uncle, such as Mill Creek Park, Congress Lake Club, and the wonderful Brookside Country Club in Canton. Brookside had the most impact on me, with some fantastic holes, and a set of the most unique and bold greens I’d seen at the time. Brian Silva has completed a restoration since, which I hear is fantastic, but unfortunately I have not been back to see.

The 18th at Brookside CC in Canton, Ohio. One of Ross’ finest, featuring incredibly bold internal green contours. Courtesy of Brookside Country Club.

After college, I was lucky enough to play in a handful of state and national amateur events. The most impactful was when I played in the British Amateur, at Royal County Down Golf Club. This was a course unlike any I’d experienced. Incredibly rugged golfing terrain, with loads of blind shots over massive dunes, and the inherent uneasiness and deception that comes with this. The wild long grasses and gorse everywhere, and the famous “fringed” bunkers that captured way too many of my shots to allow me to comfortably miss “the cut”. These imposing hazards, accented with tufts of tall natural grasses of contrasting colors along the top, have the effect of vertically immense bunkers where escape seems quite difficult, and matches the scale of the landforms so well.

One significant takeaway of this golf course was that there really needn’t be any rules followed to have a great golf course, including the finest in the world. It remains in my personal “top 5” for many reasons, but mostly due to the fact that it is completely its own golf course, and possesses its own “sense of place” unlike any other. There is not another course even remotely like Royal County Down that I can think of.

Any particular hole at Royal County Down strike your fancy?

The 13th hole was particularly appealing to me, and I don’t think it’s one of the most frequently talked about holes there. I wrote about this in Paul Daley’s Golf Architecture Worldwide Perspective book (v. 3), in more detail, but will touch on what I love about it here.

The 13th is different than most of the holes at Royal County Down in its tee shot, with the driving area actually visible ahead of you, the fairway nestled into a valley two dunes ridges. Clumps of gorse were scattered about, but predominately the tall natural grasses covered the lower-lying ridge on the right side, immediately adjacent to the fairway.

What I really admire about the hole is how the right dunes affect the approach shot, both visually and mentally. At about 100 yards short of the green, scattered with a variety of nasty bunkers, tall grass clumps, and thick gorse, this ridge encroaches completely into the centerline of the shot. Visibility to the entire green is obscured, but with the flag generally visible and perhaps a glimpse of the left greenside bunker. Depending on your position, you may get a slight gauge on the green’s proximity and distance.

It appears as if this dune requires a full and hefty carry to the green. In reality, the approach into the green is open and rewards a running shot to bound up to the pin. This conflict of what the shot rewards, and what your mind tells you not to do is what I love and is so interesting to me.

The tendency to play towards what you can see, ultimately a more comfortable feeling, lures the golfer to play towards the left side of the green. Yet this very spot is where lies the lone bunker adjacent to the green. A psychologically placed hazard if ever there was one. The greatest holes in the world are those in which the golfer is challenged both physically and mentally, and the 13th at Royal County Down checks that box.

A sketch of the approach to the 13th over the intimidating dunes ridge and bunkering, and the lone bunker left of the green that seemingly calls for your shot. Sketch by Todd Eckenrode.

How did Pasatiempo influence you in architecture?

Similar to RCD, there are very few rules followed in the design of Pasatiempo. It’s probably the wildest MacKenzie course I know, at least in the greens and green complexes. There are extremely bold and big holes such as #3, short and intricate holes such as #15, and everything in between. What’s unique about it, however, is how it utilizes the unique ravines, or barrancas, as we call them in California, on the back nine, following the land and using this identifying natural feature to the utmost. Every hole “touches” these barrancas on the back, in a different way for each hole. Carries off the tee, diagonal carries on the approach, perpendicular carries in front of the green, and play alongside can all be seen.

The result of this is great variety in play, and a sense of naturalness, as the predominate hazard is just that, natural. This was probably the thing I learned most from Pasatiempo that I try to carry into our designs. Creating variety in how natural features are used. And then carrying on that principle into all of the other facets of design, such as bunkering, green contours, approach contours, surrounds, etc

I am also very conscious of the aesthetics of design, and one of the most powerful ways in which to do that is through bunkering. MacKenzie was not shy about using bunkering quite liberally, and Pasatiempo is no exception, creating drama and a sense of artistry. Often times he would utilize bunkers on a distant background hole as part of the composition of the foreground hole, or vice versa. The original ground photos of Pasatiempo show a really open canvas, with much longer and wider views than can be achieved today.

Out of my incredibly fortunate exposure to this course came a passion and thirst for knowledge in golf course design. It was the one golf course that got me thinking… Why is it so good? What makes it so fun to play? Why aren’t other courses like this?

Pasatiempo’s 16th, featuring one of my favorite bunkers in terms of artistry. Photo by Julian Graham, courtesy of Pasatiempo Golf Club.

I have such fond memories, and am thrilled they’ve made such a concerted effort to respect and restore the MacKenzie design there. Renaissance Design has done a fantastic job there, and I’m hoping the club continues to carry on with this further.

What are your favorite holes or shots to play at Pasatiempo and why?

The obvious favorites most would state would be of #16 or perhaps #11. Those are wonderful holes, of course and interestingly have diagonal carries in varied ways. But a lesser known shot or feature that I’ve always loved is the approach shot and greensite of hole #2. The green is such, sloping away from the golfer at the front part of the green, and sweeping off strongly to the left, that you really have to play a ball that bounds in short and from this right side of the approach to have any chance at some of the hole locations in that area. The land feeds in strongly from the right, so getting the right weight on this “hold” shot is the trick and such a fun shot to try.

The 2nd at Pasatiempo Golf Club, featuring green contours that reward play bounding into the approach. Photo by Rob Babcock, courtesy of Pasatiempo Golf Club.

I’ve also always loved the greensite of #4 as well, with a unique use of a swale tucked and disguised behind the right bunker, but which really affects anything played to the right hole locations and causes a lot of deception as well.

The tee shot at #10 is a lot of fun, and probably more relevant when we were hitting persimmon woods back then! Nowadays, the kids are probably too long to play the shot over the crest of the hill as we used to, trying to gain the advantage of a ball played on the ground, down the middle, catching the downslope and gaining a much needed shortened approach to this really difficult hole.

Pasatiempo’s 10th tee shot, from Opening Day. Photo by Julian Graham, Courtesy of Pasatiempo Golf Club.

I have seen a good bit of talk of late on the swale on #14 and its understated but significant effect on play. I believe this is simply a grassed over arm of the same barranca that plays between the holes in this part of the course, but retaining it as this subtle feature was brilliant, and would have been perhaps too penal as a rugged barranca.

I’ve always had a love affair with #15, and think it’s one of the most underrated par-3’s that I can think of. It’s a hole you feel you can make up a stroke in the round here, perhaps managing a birdie, simply due to the short iron in your hand. But you’d better strike it well, and you’d better keep it below the hole. Danger surrounds most everywhere and the front and back hole locations in particular really narrow. It’s hard psychologically to get conservative with such a short shot, and perhaps you’re thinking ahead to the danger of #16, visible just to your right. You can find yourself feeling conflicted on the shot, and then…well…we know how those shots typically turn out.

Barona Creek Golf Club in San Diego was your coming out party it seems, tell us more about that project.

We started construction on Barona Creek in the late 1990’s, which was a boom time in golf development. I was working for Gary Baird at the time, running our west coast projects out of his Tennessee office, to which Barona was one. It was a really interesting project, being the first time we’d had a Native American tribe as our client, the Barona Band of Mission Indians. Also because the land was so different from what we were used to in many ways, working predominately in the Southeast United States. A wide-open and vast site, but with great internal features and beautiful vistas.

The tribe had a deep reverence for the land and this fit right into what we wanted to accomplish, which was to showcase the land, and to incorporate any and all unique and identifying aspects of the land into the routing and design. Mature California Oaks, great rock features, and things as minute as simple swales filled with cobble were throughout the site. We realized that San Diego in general was pretty void of quality golf course architecture, on the public side particularly, and wanted to do something completely different for the area. Everything else was narrow, tree lined, heavy with rough and overwatered. An open, wide, firm and fast golf course hadn’t really been tried. So we took off with those simple concepts, to present a different playing experience, and to showcase the natural features of the land in the utmost, and went from there.

With the expansiveness of the site, width and alternate routes of play were possible, and we could build strategy into the play. Bunkering was of the vast, large scale of the land, with detailed edging to mimic erosion, and integrated into the native grasses instead of being lined with turf.

Barona Creek’s 3rd Hole, a stout par-3 that rewards play over the left bunkering, bounding the ball into the green and avoiding the trouble right. Photo courtesy of Todd Eckenrode.

Another overriding theme was to create great variety. I was hung up on that at the time, I recall …. how can we change direction in the routing, how can we make this one hole unlike any other on the course, and have the play go from hole to hole in an interesting and varied way.

This was also was the first golf course I’d worked on where using water responsibly was a real focus. As such, the turf allocated was essentially designed at what was then considered “Arizona” standards, of under 90 acres of turf. And again, firm and fast was the concept in how it was to be maintained and presented for play, which superintendent Sandy Clark, who has been there since the beginning, does a great job with.

Toward the end of the project, I finished it on my own basically, at no cost to the owners, as I just had to see it to the end and was so vested in the project and its success at that point. At that time, my partner Charlie Davison and I formed our current firm, Todd Eckenrode-Origins Golf Design, and I’m thankful that we are still going strong, nearly 20 years later.

An alternate view of Barona’s 7th, a redan-like hole with the green falling off the back-left. Photo courtesy of Todd Eckenrode.

We led a couple of renovations on a small scale over the years. The first was prior to the course hosting the Nationwide Tour Championship, where some bunkering was added, the course was lengthened a bit for those young guns, and other small tweaks were made. The second renovation was to remove an additional 10-15% of turf.

Overall, Barona Creek Golf Club has been a great success, and I still have a fondness for it like it’s a first-born. It’s hard to believe that it’s nearly 20 years old now. Frankly it’s in need of a touch up at this point, as most any course needs in that type of timeframe. But I think the unique concepts we introduced, the inherent playability and strategy that can come from that, and an embracing of openness have been a true success and remain very relevant.

Fairways are going wide and wider now in America and yet water is at a particular premium in California. How do you balance the two for your clients in California?

The second renovation to reduce more water use at Barona is a good example of that conundrum. As I didn’t want to lose any of the width of the course, feeling this was just too vital to the overall playability, strategies and alternate ways to play the holes, it was a challenging to find turf I realty felt good about removing. For the bulk of the reduction, we decided to remove the majority of the turf between the tees and fairways, and to move any tees up to mitigate any added challenge due to more forced carry. Also, rather than just remove the turf and have the native grasses take over, we introduced waste bunkering into these foreground zones, so that if a golfer ends up there, he’s more likely to have a playable shot and be able to recover.

Barona Creek’s 10th hole tee shot, before the turf reduction renovation. Photo courtesy of Todd Eckenrode.

Barona Creek’s 10th hole tee shot, after the turf reduction renovation, highlighting the addition of the foreground waste bunkering. Photo courtesy of Todd Eckenrode.

On other projects, we are certainly cognizant of this opposing direction you mention. While I love the integration of the surrounding landscape into the golf, and feel we have to be absolutely responsible in the water use of any golf course, new or old, width is one important factor in creating playable and interesting golf, perhaps the most important. So we aim to limit the turf and water use in other less critical areas, such as around tees, behind greens, etc., where fewer golf balls go.

Tell us about some of your newer courses of note.

The Links at Terranea was a unique project due to its limited acreage and incredibly scenic site, on the bluffs of coastal Palos Verdes in Southern California. An interesting past use, it was a Marineland that had closed decades before, and also a site for shooting many films and television shows over the subsequent years. How many golf courses occupy land once housing killer whales!

The owners were proposing a high-end hotel, some residential components, and there was a “golf” envelope in the middle that was tentatively planned for a driving range or other similar use essentially. Fortunately, we were successful in ultimately convincing them to build a short course, consisting of nine par-3’s and some practice areas. Who would want to come to this beautiful site, turn there back to the ocean, and pound balls for hours on end? Not me! I’d much rather grab a few clubs, go play some shots with the whole family or some buddies and have a great time.

There was purposeful intent to not dumb it down, to keep it challenging yet playable, as well as dramatic and engaging, much as the site itself. The approximately 30 acre golf site is approximately half playable turf, and half drought tolerant natural grasses and native, coastal landscaping. The bunkering is flashed and of a natural appearance. Borrowing from the Barona concept, the bunkering is often used in playable areas, as a means to reduce the turf footprint, but still keeps the golfer playing golf, and not lost in the landscape, so to speak.

The Links at Terranea’s 3rd hole, a dynamic 175 yard hole from the back tees, but offering a playable forward tee as seen to the right, allowing easy access into the green utilizing the slopes. Photo courtesy of Todd Eckenrode.

This was also the first project we thought through providing forward tees that offered high playability, but also had the same “fun factor” as the back tees. These tees were assimilated into the fairway cut, essentially, so that a topped shot will often roll all the way to the green. And often the angle of the tee allows the greatest use of the run-in slopes, feeding the ball to the green. When we started our youngest child, Jack, in golf, we would go play Terranea with him…sometimes just a few holes in all. He couldn’t have been 5 or 6 years old, but he could somehow get enough force on a driver and the ball would bounce, bounce, bounce, and roll onto the green. What a thrill that is to witness, and I hope this has been the case for many families. But as I mentioned, if you step to the back tees, it’s presented more as a series of par-3’s you might find on a full course.

Jack Eckenrode (age 6 at the time), striping one onto the 8th from the forward tee, incorporated into the fairway cut. Photo courtesy of Todd Eckenrode.

Again, the focus on creating variety was great, which is especially difficult when the par is the same 9 times in a row! But with varied lengths of approx. 100-180 yards, and bunkering concepts that include a small, central pot bunker, a long diagonal of bunkers, and everything in between, I think we were successful in that aspect. We get back there with the family quite often, and it’s a blast to see my little ones playing those forward tees and enjoying it as much as my wife and I (who’s beat me once or twice, but let’s not talk about that…).

How about your recent project in Louisiana?

This was quite an experience for many reasons. The course was originally called Mojito Point when we first started the design, but is now named The County Club at the Golden Nugget due to the current ownership. It changed hands three or four times in the course of building it, and we were somehow retained throughout, which is probably no small feat! The site was exciting and held great potential in some ways, namely that it was a core site, and that it had quite a bit of river or bay frontage, on the Calcasieu River, part of that being a cove called Indian Bay. The downside of the site, however, is that it couldn’t have had 15 feet of elevation change throughout, and much of this was swamp. I began to channel Pete Dye, and think, what would Pete do….

What little soil present was mostly old dredged material from the river (many decades prior), and wasn’t stable at all. But there were two or three areas in the middle of the site that were native sandy hillocks, with the lone native pine trees interspersed throughout, offering some hope!

So the routing focused on a couple of things. How do we best use the riverfront to get the best holes possible on that unique edge. And how do we maximize the use of the sandy, pine-studded areas. In this sense, I thought back to MacKenzie’s use of the central hills across the road at The Valley Club, and how he played greens into them, played from atop them, and played from one to the other. We would try this, albeit on a much smaller scale.

Ultimately, we were able to route nine or ten holes into these areas, and finish with five holes along the river, to which we were quite happy. The rest of the project focused on how to build something very fun, interesting and varied on dead flat swamp!

Another major concept we had was to not just put catch basins down the middle of each hole due to the flatness of the site. This was the solution at the Fazio course next door, and we desperately wanted to be different from that course. So in general terms, we would build up one side of a hole, slope it to the other to get positive surface drainage to the site, and place the storm drainage into waste bunkering areas or drain to remnant lakes that made up the “lows” of the site. A lot of material was brought in from off-site to accomplish this and to get the greens above flood levels as well, so credit the owners for this hefty investment.

Hole #7, a par-3 turned back into one of the pine-studded sandy areas, and pitched to the left to promote a shot in from the right.

Joe Hancock was our lead shaper there, built all of the greens and surrounds and did a great job. Working in the middle of summer in Louisiana is no picnic, and often we would drive around the site in the ATV’s just to generate our own breeze and get the bugs off!

What else do you learn from this project?

One lesson learned from this project was that once our work is done, if the owner doesn’t understand or agree with the design concepts, the ultimate potential of the golf course can never be reached.

I returned to play soon after and was really pleased with how well the superintendent Reid had it playing, but incredibly disappointed to find the changes dictated by ownership. Hundreds of ornamental plants placed at perfectly regimented spacing, often blocking views for the golfer into the hazards or the hole. Where it was meant to be open and vast, was now constrained and “framed”, but in the most unnatural way. Also, the great short-cut chipping areas and surrounds that we’d created with Joe around every green had been grown out, with the rough brought in to the front corners of every green, making the presentation much like a course out of the 80’s and not in touch with classic or current sensibilities.

The riverbank shore had also been allowed to grow out to such extremes that the really interesting cape-like hole at #15, where the green was visible from the tee, luring the golfer to give it a go, or at least bite off whatever you choose, was rendered as the most awkward layup-type hole. The golfer had no idea what was above and beyond the high reeds, and as such what was once one of the best holes, a true risk/reward short par-4 along the river, plays as potentially the worst hole on the course now due to this lack of visibility.

But what can you do? I only hope they realize how out of touch these changes are with what golfer’s want and what’s most engaging, fun, playable and interesting. It’s got great potential, if presented as it was designed, or meant to be.

The 16th hole plays along the river shoreline, and thankfully is mostly cleared on the left, allowing a full view to the water.

How frustrating and I am sorry to hear all that. On a more positive note, tell us about your upcoming project in Cabo, Twin Dolphin Golf Club.

There is a long history here, starting before the recession. We have completed probably over 20-30 routings over the years, due to various options of planning, road shifts, etc. I can’t tell you how many walks traversing the site we had, really getting into the details, using GPS to record features to note for retaining, and that type of thing. The goal being to preserve as much of the cool stuff found in the routing walks as possible. The owners eventually selected the last routing, which we were really happy with. This kept all of the holes on the uphill side of the land, away from the ocean directly, but with big, vast ocean views on nearly every hole. It was really the best thing that could have happened, as it freed up the golf to be more “core”, to utilize all of the amazing features of the land in this larger golf area, particularly the “arroyos”, which are dramatic, rugged, desert washes of a huge scale with sandy bottoms.

The staking for the 11th green can be seen on the plateau over the rugged arroyo. This hole, informally dubbed “GV”, has survived every routing option due to its quality and uniqueness.

The construction eventually came to fruition early last year, and the team reassembled, including Fred Couples, who’d been involved at the outset as well. Fred was brought on board to provide his valuable input to the golf course, so it will be a Fred Couples Signature Course, and we are the golf course architect of record. Fred was a pleasure to work with, and far more involved than I would have guessed at the outset. He really took a liking and special interest from the get-go, and there was a definite value in having him involved, as everyone felt this was going to be a unique design and really first-rate golf course. He took numerous visits to the site, and his input was excellent. It’s been great working together and I think the course is better for it, which is really what’s important in my mind.

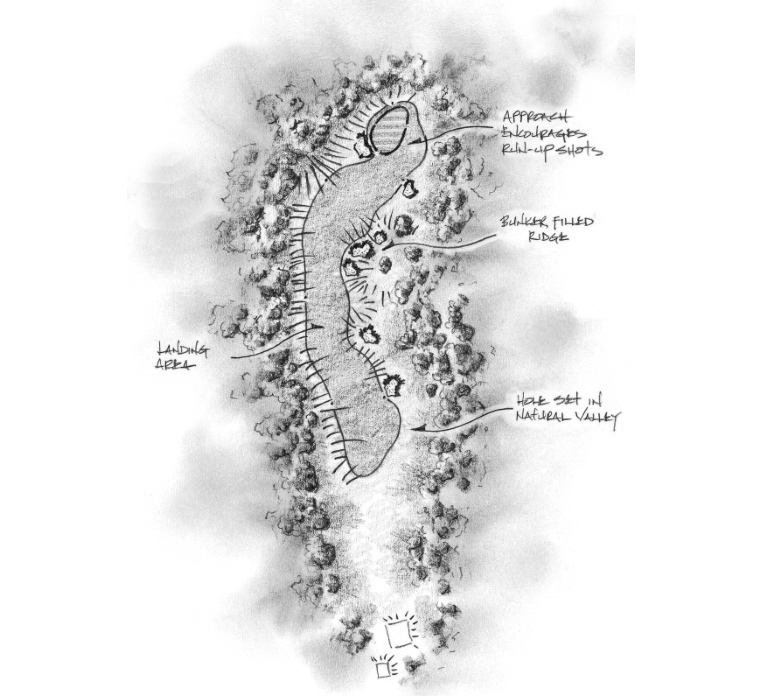

The 3rd hole plays into a natural valley, seen here from the landing area of the tee shot. The 4th green sits above as a backdrop, with the ocean beyond. The juxtaposition of these holes and bunkering will make an interesting composition when complete.

The routing traverses the site with constant variety. There are ridge-top holes set above the arroyos, holes that play over the arroyos directly or diagonally and a few holes that run in the broadest valleys of the arroyos as well. The par-3’s are particularly strong and unique, and there’s a fun 19th par-3 as well, on the way home.

Rough shaping in progress on the fun, short 19th hole, or Gambler Hole, on the way home, with the future clubhouse above and to the right. The arroyo in front, to the left, and beyond makes anything to the left side of the green a daunting prospect.

We strove to provide a lot of contour to the holes as well, in the most natural way possible, mimicking the native surrounds. No artificial lakes, nothing unnatural. If you look off into the desert landscape, there is a lot of erosion that creates these great little ridges, knobs and such. So we tried to bring this feeling into the holes as well so that it would appear seamless.

I am truly more excited about this course than any project we’ve done, as I have no doubt now that it is going to be fantastic. The melding of the rugged nature of the site with the natural feature-work by the shapers is beautiful.

Andy Frank, our Senior Designer at Origins Golf Design, was integral to this project from the get-go. While I was on-site over 100 days to date, and handled the majority of the field work through the completion of shaping, Andy really took a lead role in the finish work and final field adjustments at the end of the project and was vital to the overall quality.

Shapers included Jonathon Reisetter, Blake Conant, Kye Goalby, Clyde Johnson and Cliff Hamilton, who has been invaluable and on for the duration. What a crew! Their impact to the project is profound, and in truth, it was great to have all these different eyes on the project as well.

We owe much of what you’ll see out there as far as features go to all of these guys. As anyone in the business knows, it really happens in the dirt, and not on plan, and this whole crew nailed it in that regard.

We are quite excited to see the Twin Dolphin Golf Club continue to finish well. Grassing is underway, and an opening is forecast toward the end of the year.

End of Part I

Part II follows in May, focusing on the restoration and renovation aspects of Todd Eckenrode’s work and ideology.