Feature Interview

with

Mark Chalfant

December, 2017

Does the title Devereux Emmet – The Forgotten American Master make it self-explanatory as to what compelled you to write the 135 page book? You liken his work to being underappreciated like that of the work of William Langford, Vernon Macan, and Walter Travis.

From thirty years of playing, caddying and evaluating architecture for Golfweek Magazine and the Metropolitan Golf Association in the greater New York area, I knew that Emmet was an unsung talent. Daniel Wexler’s book Lost Links was an eye opener because he stressed the exceptional variety of holes and idiosyncratic sequence so prevalent in Emmet’s layouts. Wexler also highlighted the architect’s fondness for short par fours.

Even though Women’s National (now known as Glen Head Country Club) was cramped with trees when I caddied there two decades ago, I could tell it was a superb layout with nicely paced elevation changes.

When I read Geoff Shackelford’s February 2001 article in Golfdom outlining Huntington Country Club’s restoration, I became even more intrigued with Emmet.

What sources provided you the best research material?

The most important source for me over the past five years has been visiting twenty-six of Emmet’s existing courses. Also poring over aerial photos usually dated between 1924 to 1959. While working on the book I made ninety pilgrimages to these Golden Age layouts.

Two trips stood out, first to Huntington, Long Island on a raw November morning and a few months later to Bonnie Briar up in Larchmont. Each made an unforgettable impression and compelled me to write about this imaginative pioneer. At both Huntington and Bonnie Briar, Emmet built rugged works of art that play just over 6,300 yards and that possess a spellbinding assortment of par fours.

Old magazine articles were of course essential tools. The Los Angeles Athletic Club website LA84 had several articles that provided critical historical context. Some articles by Marion Hollins were especially helpful.

I am grateful to dozens of Emmet fans including Joe Bausch, Jim Kennedy, Tim Martin and Ian Andrew. Professor Bausch sent me scores of articles from the Brooklyn Eagle and course diagrams in New York World Telegram that were beneficial. Joe’s faithfulness kept me focused when my body and soul were yearning for a binge of rounds at Seth Raynor and Donald Ross courses far afield.

Please discuss how Rockville Links showcases Emmet’s talents as a designer.

When Emmet first laid eyes on the potential site, it was a compact and slender 97 acre meadow that had virtually no ground movement. Emmet countered with a scintillating bunkering program overflowing with tactical puzzles. The hazards have stunning variety in shape, size and orientation.

Additionally, the fill pads and interior contours of the greens are constructed with exceptional nuance. Architect Jim Urbina, Jeff Stein and greens keeper Luke Knutson have done a superb job of recapturing Emmet’s original intent.

Emmet’s architecture at Rockville passes a key litmus test: what can be created from a featureless site. Great architects are able to elevate mundane sites. For a student of the game or a prospective golf architect, Rockville is an essential destination.

Garden City GC is a huge personal favorite. On the one hand, Emmet routed the course and built it, presumably to his own satisfaction. On the other, Walter Travis was quick to both praise the design and re-bunker it. Given how talented Emmet was with cross and strategic bunkering patterns, why was Travis’s work even required? I have never felt like I understood the full story on why Travis went on a bunkering binge at Garden City Golf Club.

From its 1897 nine hole beginning as Island Golf Links, Garden City had a solid routing. After the 1902 Open and some other tournaments, Walter Travis felt the course played too easy. He rallied members to invest in a bold bunkering plan. In the subsequent twenty years, there was a lot of back and forth between Travis and Emmet.

Emmet outlived Travis by seven years so he enjoyed the last word. I like much of the Travis bunkering. It is certainly high in quality, but perhaps a bit overdone in quantity. The brilliant angles via echelons that edify Garden City’s brilliant sixteenth are Emmet’s handiwork.

‘Natural contours rule the day’ seems to sum up Emmet’s approach to placing fairways, and occasional blind shots were even a consequence. What are three of your very favorite Emmet fairways?

Pelham’s ninth and McGregor’s long sixth spring to mind as they have a powerful wave like quality.

Willow Ridge in Harrison lies only six miles east of Winged Foot, has several holes rising and descending near the clubhouse that are blessed with a combination of elevation change and robust ground movement. One, nine and eighteen are especially strong, even though their fairway corridors are parallel.

In general, Emmet’s routings demonstrate an inspired integration of native topography and sensitivity to scale which creates procession of unpredictable challenges. This skill holds true whether it was intimate or monumental. The Rockville Links and Bonnie Briar are perfect example of intimate while McGregor, Wee Burn, and Glen Head are all striking for their broad-shouldered monumentality.

Finally Garden City’s ground movement, not bold in the least, has some of my favorite quiet fairways that melt into many greens seamlessly at fairway grade. The tenth and fifteenth, both low profile, are especially well-conceived. Their putting surfaces are expansive tilting ground, front to back or side to side for their character.

Please talk about one your favorite bunkering schemes at Huntington Country Club.

Several of the hazards are breathtaking, starting with number ten, eleven, fifteen, and sixteen. Golf Architect Ian Andrew considers the bunkering here exemplary.

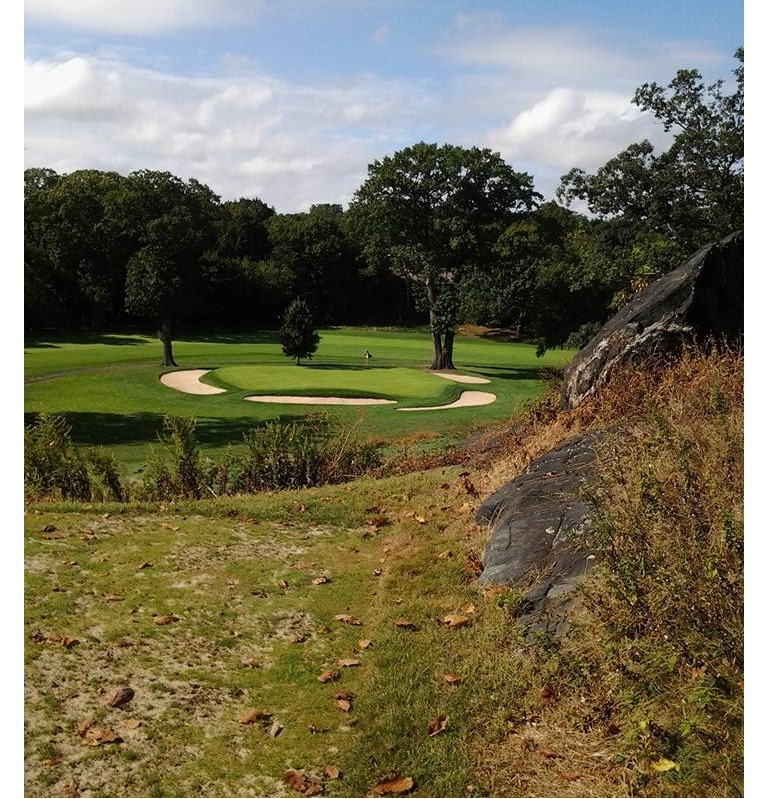

Eleven is a short par four that has mine field protecting the fairway’s right side while ahead, punishing traps protect the green. The exuberant plan on sixteen includes eccentric shapes that invade the gently rising fairway. The otherworldly/alien bunker can snare wayward shots on number eleven which borders the sixteenth.

Huntington 16: Because of Emmet’s fertile imagination he rarely embraced templates.

My heart breaks at the sight of the housing that smothers parts of McGregor Links. Having said, the shell of great holes abound there – what are some of your favorites?

The stretch from three to seven is one of the most compelling that our master ever created. The third is an option filled 231 yard par three with cross bunkers and a superb cupped green.

McGregor’s fourth has superb fairway undulation that impacts level stances and sightlines throughout its 320 yards.

Ten and fourteen are an architectural rarity: two medium length par fours overflowing with character. Superb green sites abound all over the 1921 layout, including plateaus at ten, thirteen and sixteen.

The 17th is a fine homage to the Alps prototype and its putting surface is a gentle punch bowl.

Was St. George’s Emmet’s own National Golf Links of America and did he spend the most time working there than any other layout?

The National Golf Links of America is Macdonald’s personal version of St. George’s – Not really!

Emmet owned a wonderful estate near Saint George’s but he also had a home in Cooperstown. He took extended trips to Europe nearly every year even when his business was thriving. He was an accomplished golfer, cultural patron, and expert huntsman.

St. George’s is a superb golf course that he lavished great attention on but he also did the same at Meadow Brook, McGregor and Garden City. Perhaps the lull of construction between Meadow Brook (1916) and the second nine holes at Leatherstocking (1919) caused by World War One provided some extra investment of time at the Setauket masterpiece.

Please expound on your statement: ‘Above all Saint George’s is a museum of early Golden Age bunkering.’

Let’s clarify my earlier summation of this transcendent work of course design.

Yes the tactical sophistication of the sandy hazards is marvelous. However the integration of hazards along the ground, angles of play, and the seamless interplay of shared fairways are a sight to behold. This 1917 layout epitomizes Devereux’s recurring motif of remarkable changes of pace.

The bunker–scarred 570 yard second fairway offers numerous paths to get home, its putting surface flows effortlessly from the fairway’s quiet grade. Conversely, the challenge on third hole stems from its rambunctious sloping fairway, which offers few level stances. Accordingly distance control to the downhill target is unforgiving.

The drop shot seventh and the uphill tee shot on eight form yet another superb study in contrast at Saint George’s. Such inspired ebbs and flows pervade the entire golf course.

Like playing the game at Garden City and Myopia, at St. George’s the avid golfer experiences a vital, historic sense of place.

Clearly Emmet was a pioneer of the American golf architecture scene.

With the completion of Saint George’s by 1917, Emmet had built a solid resume. In terms of quality he was only equalled or surpassed by one American based architect, a man by the name of Donald Ross. For example, four courses Garden City (1899), Cooperstown (1909) Wheatley Hills (1913) Meadow Brook (1916) were completed before Emmet’s landmark Saint George’s in 1917. Alister Mackenzie did not work in America until 1926. William Langford and A.W. Tillinghast were just getting started.

A concise way to sum up Emmet’s professional stature at that point in time is quantity, quality and that his early work was groundbreaking.

What pleasant surprises did you come across as you dug into Emmet’s work?

Hob Nob Hill for its routing and bunkering!!!

The topsy-turvy terrain that makes Keney Park’s first six holes so fun.

Emmet’s creativity at Queens Valley and Powelton.

The exceptional variety of holes at Meadow Brook Hunt (1916).

The strategic affinities between Devereux Emmet’s bunkering at Queens Valley, McGregor and that of National Golf Links of America.

Many people don’t appreciate the deep and lasting friendship that C.B. Macdonald and Devereux Emmet enjoyed. How much was Emmet involved in the evolution of National Golf Links of America?

Charles Blair Macdonald, Devereux Emmet and H.J. Whigham were all close friends. Devereux Emmet, at Macdonald’s request, visited numerous golf courses in the British Isles to study and make detailed drawings of exemplary courses and some off the beaten path.

In some cases, he made sketches of specific elements of individual holes. These prolonged visits occurred before actual construction began. I had several conversations about Golden Age architecture with the late George Bahto. We spoke about Shoreacres’ routing and the marvelous bunkering at St. Louis Country Club.

In regards to National Golf Links of America’s evolution, George told me that Macdonald was conceptual and the big picture guy. Then George emphasized that during actual construction, Devereux Emmet and Seth Raynor were the hands on men.

As our long conversation winded down, the historian noted that between Emmet and Macdonald ‘ Mark, there was a lot of cross fertilization in their design tendencies.’

How often did Emmet travel to the United Kingdom? You note how important his trip to North Berwick was in 1883.

Emmet was there almost every year for three decades. Emmet admired the Old Course and North Berwick, which is where he preferred to stay during extended visits of up to six weeks.

What other courses overseas impressed him and ultimately influenced his architecture back in North America?

The two courses he found most inspiring were North Berwick and Prestwick. The following describes the day of a sportsman in Ayshire.

We saw the Park and Fernie match at North Berwick Links The following days I played matches at Troon. One time I played foursomes with Sybil Whigham at Prestwick. Prestwick, near Troon is my favorite Links.

Although he held both Saint Andrews and North Berwick in very high regard, Emmet made it clear that he felt template holes were overdone in America, especially the common models for par three holes. He felt there was an oversupply of Redan and Eden holes in the United States as there must have been over twenty Redan Holes south of the Canadian Border!

You most lament the passing of which of his designs?

The high quality of many of his golf courses no longer exists, which certainly plays a role in why he remains underappreciated. Pomonok, Queens Valley, Hob Nob Hill are all discussed in the book.

In their present state, which of his designs would Emmet be most proud of today?

Garden City, Schuyler Meadows, Saint George’s, Glen Head, and Huntington.

Which courses would most benefit from a proper restoration?

The Powelton Club in Balmville, New York twists and turns over rugged terrain. A few refreshed bunkers and prudent tree management to open picturesque vistas would elevate this 6,189 yard course into Emmet’s upper echelon.

Ridgewood in Danbury, Connecticut with a hilly routing features precarious green sites, a winding brook, and sidehill approaches to small targets. Retooling the ponderous twenty first century bunkers, to their proper size and configuration would add authenticity and coherence to this scenic golf course.

Wee Burn is a well preserved masterpiece with a fine ensemble of par fours, and the stretch from eleven through fourteen, winding around a creek, is one of his finest. It would be fabulous if several original centerline bunkers were restored.

Pelham Country Club is beautifully presented by greens keeper Jeff Wentworth. It’s a sporty course with many good holes and vintage greens. The long and flat third fairway originally had a looping stream that crossed the hole twice. There was also a well-placed fairway bunker. The stream beds are still intact! Properly restored Pelham’s third would become one of the best par fives in Westchester County.

Hampshire’s 8th measures 302 yards. Emmet believed short par fours were essential elements because they added fun for all golfers.