Feature Interview with Kris Spence

August, 2017

1. How does your background in golf course maintenance and construction help you compete for projects?

Both backgrounds compliment my approach and understanding of golf architecture in multiple ways and the best way to answer the question is with a recent example. I interviewed at Sara Bay Country Club in Sarasota, Florida along with other architects for a possible restoration of the greens and bunkers to what was shown on the 1926 Ross drawings. The greens are severely domed from a previous renovation rendering 50 to 60% of the putting surfaces unusable for hole locations. The slopes radiating out from the center of the greens and down toward the edges range from 5 to 10%. With some investigative work, we discovered the root zone depth to be 24″ deep when only 10 to 12″ is needed. We took physical property samples of the root zone mix 12″ below the surface and found it to be perfectly suitable for the new Tifeagle greens. The value in this discovery will allow us to restore the greens without reconstructing them, saving the club over a half million dollars.

At the same time, reducing the center elevation 12 inches will restore a suitable slope range for hole locations between 1 and 3.2%. The Ross plans show rolling spines, tiers, small plateaus, swales and ridges, none of which exist today. We will reclaim those wonderful old Ross greens and features for a modest price compared to rebuilding them. The savings will be redirected to a more thorough restoration of the Ross bunkering shown on the drawings.

My background and experience played a vital role in my getting the project and also in developing practical and economic solutions to help Sara Bay restore its Ross course. Bob Gwodz, the GCS at Sara Bay, has been at the club for 32 years, I think. Not only will we work together on the restoration project, but I will consult with him going forward on better defined mowing patterns, improved bunker performance, tree management and approach firmness, all issues that I bring to the table from my background as a Green Keeper.

2. What are the pros and cons of owning and operating both the design and construction components of your business?

Let me say it was not always my intention to become a design – build architect, it came about through my frustration trying to get some contractors and shapers to put what I wanted on the ground. I had a pretty extensive background building and maintaining golf courses prior to hanging out my shingle. It seemed like the first 4 or 5 projects I did, I spent a great deal of time training or trying to convince the shaper how to implement my ideas.

After a while, I realized I was doing the selling, overseeing, training and they were making 2 or 3 times more money off my efforts than I was. Around the same time, my old boss, the former golf course superintendent at the Atlanta Athletic Club and Pinehurst Resort, Jim Ganley, was looking to step back from his design/construction company and agreed to help me get established with my own. Our first project together was Mimosa Hills, an original Ross course in here in North Carolina. That was 15 years and 50 projects ago.

The ‘pros’ start with having control over the finished product and being able to spend more time on the job. I’m hands on with design and construction, and like to get in the dirt, shape a little bit, look at the rough shaping from the golfer’s view and pass it through my visual filter. Plans are great but nothing beats getting out in the dirt during construction. At times I shape some of my own stuff, however, most of that falls on my Associate Jim Harbin. He is way more talented than I will ever be and has shaped golf courses all over the world.

The ‘con’ of owning both is the increased work load which is only a problem when I get busy. I like having a full plate and generally do, but at times, the added role of construction company owner can get overwhelming. I am slowly handing over more responsibilities to key employees.

As an aside, I enjoy ‘design only’ gigs too. Mooresville Golf Club was a project where we designed and shaped the job, Southeastern Golf followed us with construction and it was refreshing.

3. Given the paucity of new 18 hole designs, today’s opportunities largely lie in either restoration or renovation. What are the crucial ingredients for a successful restoration? I assume a key club member as champion of the project and a talented Green Keeper who buys into the work are two cornerstones?

In my opinion, renovation and restoration are more restrictive and require more problem solving than building a course from scratch. Without question having a key member willing to be the point of the arrow is vital in a restoration. Someone on the team with a clear understanding of the club’s pulse is vital. Restoration is not as cut and dry as some want or think it should be. There are clubs that want the course put back just because it once was and others that want to make sure the course is adaptive to the current game and suitable to the current state of their membership.

Key members are a great source of information, as are digging into club archives and communicating with older members for information. At times, the architect doesn’t have access to that information and it can be missed. I have always felt that the members know where the nuisance lies, they play the course on a regular basis, they find the odd spots and experience the problem areas and can help bring them to light.

I haven’t experienced a successful restoration without a talented and dedicated Green Keeper. The GCS and his staff are the people who take my work and make it shine, quite honestly they make me look better than I probably am. The Green Keeper who has a strong interest in the architecture, the look, the character, how his course plays and how it should be maintained and preserved is the most valuable component to the longevity and success of any restorative effort.

4. Please provide an example whereby an influential member helped you get the absolute most out of the scope of a project.

Without question, Dunlop White III at Roaring Gap Club. Without D as I call him, that project doesn’t happen. We first met at the Gap to discuss some drainage and tie-in issues around the green edges and from that meeting, the seeds of a fantastic restoration were sown.

As we discussed the drainage and tie-in problems, I pointed to the original green edges and rolling undulations that were separated from the putting surfaces. Dunlop immediately recognized that putting a band-aid on it to solve a minor problem was not the answer and convinced the club to commission a Master Plan. Dunlop gathered aerials, ground level photographs, letters from Ross, old maps and talked to some of the older members to ascertain what Ross’s original course was like. He lobbied for the monies and commitment from the committee to support a restoration plan.

We then developed a written list of recommendations followed by drawings and sketches and got to work. The project started out with tree removal, bunker restoration and adding some new tees. The sheer volume of tree removal and peeling back the layers to restore the width of the holes was tenfold any prior experience for me. Dunlop had a vision for tree removal and opening of long vistas unlike anything I had experienced. I learned a great deal from him in that regard.

Going forward, most of the committee members were not that excited about a large scale restoration, mostly they wanted to address the small issues with drainage and move on. Dunlop was the one who built a consensus among the key members that a full scale restoration was in order and pushed it over the finish line. Dunlop and I have remained friends and I value his opinion a great deal. We communicate often on issues relating to not only the Gap but my other projects as well.

5. Please walk us through the green restoration process at Roaring Gap.

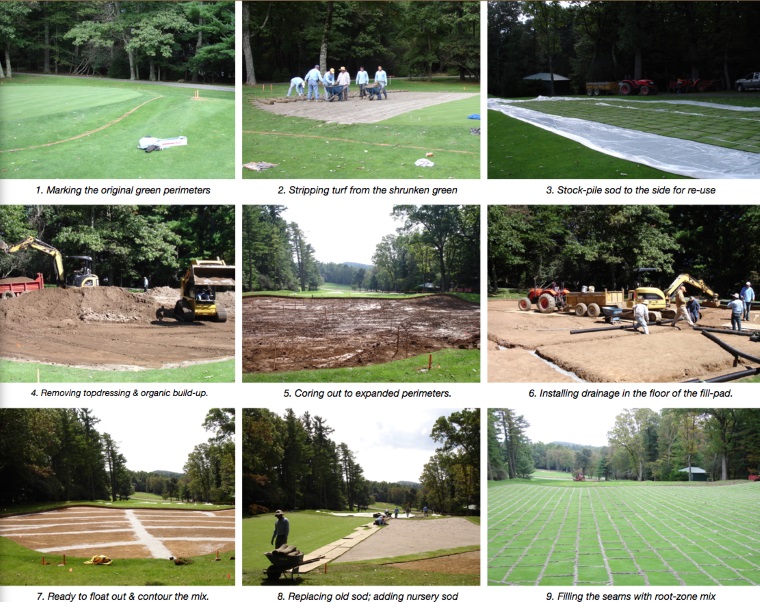

The greens at RG were about 90 years old when the restoration occurred in 2014. From the time Ross constructed the greens in 1924, approximately 8 to 10” of sand and organic build-up from topdressing and growth had occurred, but only on the area being maintained as green. In essence, the area representing about 60 to 65% of the original Ross greens had increased in elevation by that amount while the non-maintained areas of the Ross green did not. This resulted in a raised circular domed pancake in the center of what was once squarish Ross greens with strategic hole locations in the corners and wonderful rolling undulations along the edges, none of which had been in play or part of the putting surfaces for well over 50 years.

From day 1, I insisted that we remove the “pancake” first before rebuilding the greens. The pancake profile was convex while the original Ross green had more of a concave shape. We exposed the original Ross putting surface, cleaned it off, checked the slopes and grades prior to coring down to reconstruct the green. In this manner, we reset the original Ross green elevation back to the 1924 level, thus eliminating the blocked surface drainage that started the whole process and restoring all of those wonderful outer hole locations near the fall-offs, bunkers and undulations. In addition, removal of the build-up material revealed the irregular horizon lines along the back edges and sides of the greens that Ross so often mentioned in his notes. Such horizon lines had been previously blocked from the player’s view by the raised pancake.

In hindsight, had we left the build-up in place and graded the raised green to taper down to the outer edges, it would have produced a set of crowned greens similar to what exists on the Pinehurst #2 course. We performed a very similar process in restoring the greens last year at Memphis CC, a 1915 Ross and will follow suit in 2018 at Sara Bay CC in Sarasota FL, a 1926 Ross.

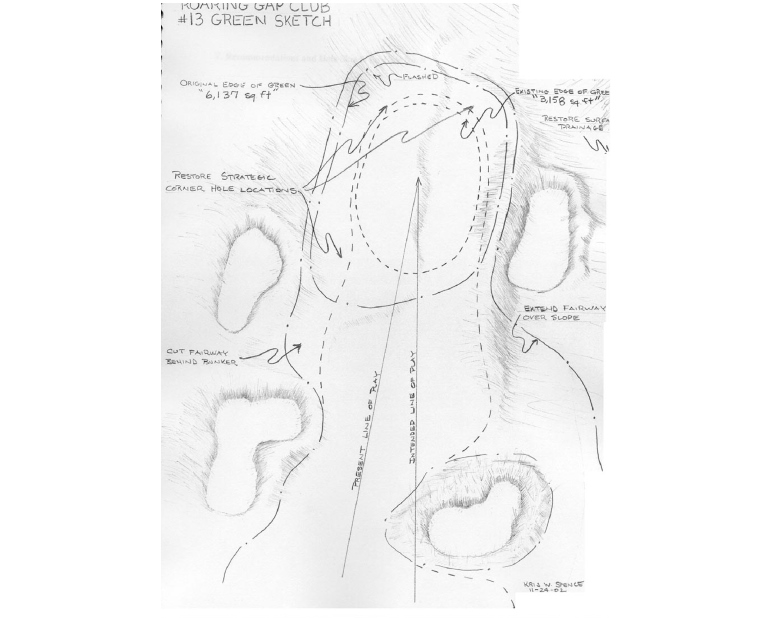

Below are a couple schematic sketches to illustrate the process at Roaring Gap.

6. I know we talked about this in the GolfClubAtlas Roaring Gap profile but tell us about the grassing of the greens. I have never heard of another club doing the same yet I think they would if they only knew about it.

Another unique element of the green restoration involved the preservation of their turf compositions — a native blend of 70% poa annua, 20% bent-grass and 10% mutations — which evolved this way over time. Dunlop and club officials wanted to retain the look and texture of these putting surfaces — giving their greens an old-fashioned, seasoned appearance that could only be created by Nature over time. So I decided to “recycle” their native poa-dominant turf compositions rather than fighting its invasive nature on an unblemished, clean bent-grass surface.

As a result, we stripped the green surfaces and stockpiled the sod to the side for re-use after re-construction. Since the new green perimeters were expanded to their original footprints, large amounts of additional sod would be needed. Superintendent Erik Guinther and I made certain of its availability by creating a 20,000 s.f. green nursery, which we harvested from aerification plugs the prior spring. Because the nursery germinated from their native poa-dominant green compositions, the turf supplementations during green expansion theoretically resembled the age-old native sod used on the rest of the course.

But in order to prevent the newly germinated sod from “clashing” with the old native sod on the expanded perimeters, we devised the following strategy. The additional sod needed for green expansion on the first hole would be borrowed from the green sod cut from second hole. The additional sod needed for green expansion on second hole would be borrowed from the green sod cut from the third hole. We kept borrowing from the greens ahead, until eventually there wasn’t any turf left to borrow.

At that point, the amount of sod needed to cover the remaining greens at Hole 7 – 9 would be taken directly from the 20,000 s.f. nursery. The rationale being that I wanted to use sod with the same maturities on the same green. While it may be obvious to distinguish old native turf from newly germinated nursery turf when laid next to each other, any differences in color, texture or maturity proved to be unnoticeable when utilized on separate greens. We successfully executed this process nine holes at a time over a two year period.

See pic(s) below…

…and the finished product with all the interesting hole locations restored and the greenside bunkering reconnected with the putting surface.

7. How do you work with the Green Keeper to preserve and maintain the design long after your spadework is complete?

During the plan development and project construction I spend a great deal of time building an understanding with the Green Keeper about the architecture. It is very important that they are on board and understand the importance of the shapes, look, feel, character, angles, philosophies and playing characteristics of a classic golf course etc. Once the project is complete, the Green Keeper can call me anytime with questions or issues. I usually stop by at least once a year, sometimes more if I’m travelling through the area.

The two most common issues where an ongoing relationship is needed are mowing lines and bunker maintenance. Mowing lines tend to migrate over several seasons and bunker sand is in a constant state of motion. Therefore, it is important to keep an eye on both.

Tree issues are also a routinely discussed item. No matter how hard we try to get all the trees down during the project, more tree work is always needed.

8. It is hard enough to build great golf, sometimes environmental challenges can make it seemingly unobtainable. Describe a couple of your more challenging environmental hurdles to date, including that of the woodpecker in Moore County, and how you handled the situations.

We use environmental consultants on a regular basis that guide us through the regulatory process. Even with their help, obstacles can greatly influence the final outcome of the design process. I have to admit that I sometimes let my frustration get the best of me when dealing with the out-of-control regulations. Some areas are worse than others, it’s part of the process. I for one love meandering streams or creeks in my work, it is damn near impossible to use an existing stream feature in golf design today unless it’s an artificial recirculating stream. Amen Corner would look different if Mackenzie had to design and build it today.

Most of the time, wetland or sediment control are our biggest challenges, but in the case of the Country Club of North Carolina, the Red Cockaded Woodpecker (a federally protected bird) was the major obstacle. CCNC is considered the most successful site in the world for preserving the habitat for this small and elusive bird. While I applaud their efforts in preserving this endangered bird, their presence and the restrictive regulations were difficult to design around. Not only do you need to avoid the nest trees, but tree cover in their cluster groups greatly restricts tree removal for shade removal and/or relocating a green or bunker etc. Both came into play on the Dogwood Course renovation preventing the relocation of the 18th green where I wanted to add 25 yards to a 510 yard par 5 and shifting the 11th tees left for a better tee shot line. They also impacted the placement of several fairway bunkers and tree removal in widening playing corridors.

On the Lake Toxaway project, we were building a golf course along class 1 trout streams and lakes under heavy oversight and regulation. Sediment and erosion control were restrictive and limited us to clear, construct and grass 25 acres at a time. We could not proceed to the next 25 acres until the previous section was fully grassed and stabilized. Not only did it add a great deal of time to the construction schedule, but it added significant cost to the project. In the end, we didn’t have a single violation from start to finish which is something I’m proud of. My design of the 18th hole at Toxaway called for 2 fairway bunkers, filling in a pond and restoration of a creek. The last two months of the project it rained everyday just enough to prevent grading work due to the regulations. I was finally forced to give up and to this day (10 years later!), those two bunkers have not been built or the pond removed.

9. There is restoration and there is renovation and you renovated Lake Toxaway Country Club in 2008 to acclaim. What prompted you to essentially reverse the routing of the course?

In a nutshell, I couldn’t produce quality golf using the old routing. The owner’s father and golf professional routed the original course to maximize real estate value. Quality of the golf holes took somewhat of a back seat. Many of the holes turned at 600’ with an equal or greater distance from the landing area to the green sites. Several holes featured blind tee shots where the fairway turned forcing the player to dramatically cut the corner or end up in someone’s dining room through the dogleg.

One day while walking the course during plan development, I decided to play the front nine (now back) backward with a 4 iron to see if it would produce better golf. Before I teed off, I committed to change the direction if I made it back to the clubhouse in decent fashion. Obviously I made it back and knew that was the direction the course needed to go. I also flipped the first two holes on the other side for a total of 9 holes reversed. I ran it by the Director of Golf Lou Biago who loved it, we then pitched it to the owner Reg Heinish who loved the idea and gave us the go ahead.

10. Talk to us about the scope of your work at Cape Fear Country Club in Wilmington.

Cape Fear was a Ross course that had undergone several redesigns over its history including holes added, two holes eliminated for clubhouse expansion and parking lots. A remodel effort in the 80’s by George Cobb also altered several holes. The course was originally designed by Ross in 1926 and he (Ross/McGovern) later returned in 1946 to replace 5 holes eliminated by the construction of a major roadway. Ross / McGovern drew up a new set of plans for all 18 holes which we used as a guideline in restoring the remaining holes. The clubhouse had been placed in the middle of the old 18th fairway and 10th hole with two new Myrtle Beach style holes built on the far side of the property. They were using the old 17th as the finishing hole and driving in to the clubhouse from there.

My goal was to restore as much of the original Ross as possible and bring the course back to the clubhouse area. This required shifting the 2nd hole to the right about 70’ or so which allowed for a short drivable par 4 18th going back to the old 18th green site. I added a new 150 yard par 3 14th by filling a portion of irrigation pond. This provided just enough room for a new pedestal greensite and turned the golf course back toward the clubhouse completing the current routing.

We used the detailed Ross green plans and cross sections to restore most of the greens and bunkers.

11. Please talk about the transformation of Carolina Golf Club and how you restored playing angles to that Ross design.

Carolina Golf Club is a 1929 Donald Ross course in the heart of Charlotte and was one of my first clients after starting my architecture firm. I began working with them around 2003, soon after the 16th and 18th holes had undergone a recent redesign to a more modern concept that wasn’t well received by the membership. During my initial visit, I suggested that the old Ross holes were far better than the new ones and that the two Ross holes should be restored. The leadership at the time agree and we began work reinstating Ross concepts on both holes. The end result made them realize what they had in the way of Ross and that realization helped initiate discussions toward the restoration of the entire course.

The course itself was a mix of old Ross holes with grassed over bunkers and shrunken greens, several other green complexes had undergone remodel projects adding depressions, catch basins and symmetrical mounds etc. Extensive tree planting and years of growth had rendered most of the holes narrow, straight and repetitive and they lacked Ross’s strategic qualities. The bones were there, you could still see old bunkers where they had been grassed in. Original green fill pads were intact but separated from the green edge by 20 feet in places. Tree planting had been extensive, tree removal non-existent except for the damaging winds from Hurricane Hugo that hit the middle section of the course hard in the late 1980’s. Most of the people I spoke to about the course had fairly low expectations. However, after studying the grounds, old aerials, pictures in the clubhouse and the discovery of the Ross drawing for the course, I realized Ross had designed a pretty special course that was definitely worthy of restoration.

One of my main objectives outside of recapturing the Ross putting surfaces and bunkers was to reinstate the width, the side to side movement and the art of the recovery shot. Years of tree planting and growth along with bunker removal had created straight, narrow holes void of any angles. To bring Ross’s true philosophy back, extensive tree work (1000+ removed) would need to be done. I wanted the course to provide open vistas and enough width that the player would feel a sense of comfort hitting the drive or longer clubs from the tee. The old course was claustrophobic and too restrictive, relying on narrow corridors and tiny greens as its defense. I wanted the player to have the option of playing out wide and approaching the greens from all angles.

Restoration of the fairway bunkers brought back the angles and side to side movement. We took the mowing patterns back out to the bunkers which was staggered along the corridors providing classic Ross zig-zag movement. A side benefit of the tree removal was the expansive view and exposure of the course from the clubhouse site. Members can see 15 holes from the clubhouse terrace with a backdrop of downtown Charlotte.

Matthew Wharton is the Master Green Keeper and has been in charge of the course since the project was completed 10 years ago. He has continued to expand on natural grass plantings adding more and more character each year. It is truly one of the most incredible resurrections of a golf club I have ever seen. I use Carolina often as an example of what is possible when speaking to prospective clients about the impact a restoration can have on their club.

12. Sedgefield is clay-based. Did Ross temper his designs when he moved away from the sandy soils of Moore County? How does working in clay impact your own restoration work such as runoff areas around greens, etc.?

Topography influenced Ross more than anything but the difficulty of moving clay soils versus sand also had an impact on his design decisions. Sand afforded him natural drainage and natural sand hazards wherever grass did not exist where on clay he generally cut his bunker into slopes, mounds and fill pads where water would drain away from the bunker site.

As far as runoff areas, I use surface drainage to natural ditches, streams and lakes for discharge if at all possible. I despise catch basins and avoid them at all cost. In the case of Sedgefield, I had to use some fairway catch basis on a few holes due to the PGA Tour event and needed to insure quick drainage in case of heavy rain during the tournament. On the 17th hole, Ross filled an old creek bed meandering down the center of the hole and allowed the surface water to flow down the crease about 300 yards. The tour asked us to sand cap and basin the old creek channel to expedite drainage.

If you look at the green complexes at Sedgefield, Ross let the water flow away on all sides if possible. Some are set on side slopes with one dominant direction so they drain naturally as a general rule. I don’t think we cut any basins around the greens at all.

13. What have you learned from your experience of having a PGA Tour event played on your Ross restoration at Sedgefield each August?

To be honest, it has been an exercise in frustration. It pains me to see the way the course is set up by the Tour. They go out of their way to avoid the real magic Ross designed there, especially on the greens. The set-up criteria for hole locations apparently is 1.5% or less. Sedgefield has some of the most wonderful greens and examples of Ross’s work in this country with the entire course laid naturally over twisting and turning topography with a great set of low profile greens. Greenside bunkering is modest in number, there is closely mown turf extending around most every green. The magic at Sedgefield lies in the rolling undulations along the edges feeding softly into the putting surfaces creating pockets, deceptive slopes and small plateaus where great hole locations exist.

I’ve accepted that Ross’s architecture is not that important to the Tour staff in setting up the course, but in the end, the Wyndham has become a great event with a strong fan base and high appreciation among the players who enjoy coming to Greensboro each year.

14. At the Town of Mooresville you designed and built twelve new holes to compliment six remodeled Ross holes. What were the essential elements of Ross that you incorporated into your work there?

When I was first approached about the possibility of restoring the original Ross front nine and renovating the Porter Gibson back nine, I was somewhat skeptical in the value in doing so. After a thorough evaluation, I determined that safety issues related to Ross having to route the course around an old industrial pond, and several green and tee sites hard against busy streets made a restoration unfeasible. We decided to remove the 16 acre pond site, shift the Ross holes away from the streets and add needed separation between several holes for safety.

Soon thereafter, the town and a commercial developer requested 13 acres in the NW corner of the property requiring a completely new routing of the old Ross course. The opening green is the only original Ross green site in the new design. Holes 1, 2 and 4 are routed in the same direction and over portions of the Ross holes but that’s about it. A new 3rd hole was added and the 5 holes across the creek from the clubhouse site are a new routing. The old backside holes underwent a total remodel and renovation using the same routing and implementing Ross style greens and bunkers as a means to provide a cohesive design.

15. The Dogwood Course at the Country Club of North Carolina was designed by Willard Byrd and Ellis Maples and is considered one of Maple’s best. It has held many tournaments including a PGA event, the U.S. Amateur, and several Southern Amateurs including the one this past month. Past winners include Nicklaus, Sutton, Crenshaw and Webb Simpson. Yet, the gold standard for architecture in Moore County lies just over one mile away at Pinehurst No.2. Did you spend any time at No.2 while you worked at CCNC? If so, did you try to emulate anything at CCNC from Pinehurst No. 2?

I didn’t spend near the time at #2 as I would have liked. I have for years parked behind the 6th green and walked around studying holes 2 through 7 or 8 as inspiration for my Ross restoration work. I pulled in twice during my work at CCNC but it really was not an influence on my work on Dogwood. Ellis cut his teeth learning the business from his father and to some degree Donald Ross, but he obviously decided to go in his own direction as an architect.

The turf removal and naturalization at #2 was not an option at CCNC, the property has significantly more topographic change and surface drainage to deal with. In addition, CCNC is the premier private club in that region and does not compete with the resort courses for play. The sand exposure concept certainly came up in discussions but ultimately was not of interest to the club and its members. We did try and bring the natural Pinehurst elements a bit more out of the trees here and there around bunkers and greens but to a small degree in comparison.

16. The Dogwood has held a lofty perch among golf courses in North Carolina, yet it was in pretty tough shape when you started work in 2014. What specifically did you do to improve the playing conditions?

My initial walk through prior to the interview process left me speechless. It was just prior to the US Open at #2 in 2014, which was a very hot and dry period in the region. The tees, fairways and roughs were inconsistent under foot. You could take two steps down a fairway that were extremely soft and wet and the next three dry and crispy. Thatch accumulation from years of ryegrass overseeding and Bermuda growth had grown to a point where conventional aerification methods were no longer effective. The irrigation system was outdated and delivered inconsistent coverage and control. Standing on the tee looking down most every hole you saw little definition between fairway and rough. The bunkers were well past their useful lifespan and offered little strategy. The course needed a major renovation.

A top priority and one of the most invasive aspects of the job was to restore a firm, well drained and consistent footing under tees, fairways and approaches. We removed the top 4” of old turf / organic build-up and buried it into sand ridges located on the front nine holes within the tree areas. We added drainage to the tees and fairways and plated them with native sand material from the bury sites. This quickly restored the firm and fast conditions on the larger areas.

The tees and fairways were sodded with Zeon Zoysia, a vibrant and dense turf that contrast strongly with the Bermuda rough providing great fairway definition. We stopped the zoysa 30’ short of the greens using Latitude 36 bermuda on approaches, collars and short cut surrounds. I felt the L36 would provide a firmer and faster surface on the shorter lower velocity shots.

The majority of the greensites on Dogwood are raised with steep approaches. Previous renovations had added elevation and steepened the approaches, eliminating the option of members running a low playing shot through the approach area and onto to the putting surface. This was a high priority of the project, something the membership felt strongly about. We reconstructed five greens on holes 4, 10, 15, 16, & 18, all were lowered closer to fairway grade to provide better access. We also cored out approaches, added sub-surface drainage, sand cap and dedicated irrigation to produce a firm, fast and tightly mown running approach.

The old bunkers were a mix of original Maples work and two prior renovations by other architects. Most if not all looked to have been added to the course versus a part of the original design. Therefore, it was crucial to better integrate the bunkering into and with the fairway and green shaping to give the appearance of the original work. The old fairway bunkering was installed mostly parallel to the line of play offering little in the way of strategic angles. Many of the bunkers were deepened during a previous renovation, swales were cut leading to them to provide visibility thus narrowing the fairway widths in the primary membership landing areas. I repositioned all fairway bunkers to appropriate distances, set them on stronger angles and biting them into the fairway at strategic points. The bunkers were angled to produce more side to side movement with the intent of encouraging more shaping of the tee shot. The bunkers have flashed sand faces reminiscent and respectful of the work by Ellis Maples.

Before #1 Fairway Bunker 240 from back tee – Bunker running parallel to the center line, deepened with only one way in and out, poor visibility from tee needing swale to see, narrowing membership landing area to 60’.

Dogwood #1 After – Repositioned to 285 from back tee, cut into subtle upslope in fairway, great visibility, strategically placed, bites into the fairway. Swale filled and fairway expanded leading up to new bunker.

17. How did you balance making sure the course is suitable for today’s young bombers versus while being playable and enjoyable course for CCNC’s aging membership and their families?

CCNC asked me to perform the first comprehensive renovation to the famed Dogwood course since its inception in 1963, a project I was honored to have been chosen to undertake. After many long discussions with the club and its leadership, it was apparent they wanted the course improved first and foremost for the enjoyment of the membership. While they certainly enjoy being recognized as one of the top private clubs in the country, they were less concerned with doing things solely for lofty rankings and awards. It was refreshing to approach the job from that standpoint!

Having restored Sedgefield and watched tour players bomb it over bunker after bunker placed at 285 yards and beyond, I find trying to contain the bombers to be a fruitless pursuit and a wasted expense for the membership footing the bill. Dogwood can hold its own with any player, it has great twists and turns, very good topography and ample challenging hole locations when needed for tournament play.

One of the key elements that benefits the member while not making the course easier is the work done in the approach areas. Most average members don’t have the aerial game to carry the ball onto many of the greens, therefore, widening and firming the approach areas will be of great benefit while not making the course one bit easier for the long hitter.

18. You made significant changes to holes #4, #10, #11 , #15 and #18. Were any of these changes in Maples’s original plans? Did your own philosophy on risk and reward influence these changes?

The 4th green was raised 2 ‘ and restored closer to the plan as drawn by Ellis Maples. The old green was perpendicular to the line of play and shallow from front to back. The new green is angled toward the fairway bunker and much deeper along the line of play with 5 greenside bunkers. It is my favorite tee shot and approach on the course, a great hole in my opinion.

#10 green was reconstructed, moving it 45’ toward the fairway to provide better sunlight to the green. The property boundary behind the green restricted tree removal. I lowered the green and recontoured the green featuring a rolling plateau front right and reclaimed a strategic hole location back left.

The tee shot on the 11th had become awkward and did not give the player the option of attempting to drive over the lateral water hazard. We shifted the tees as far left as the woodpecker trees allowed and reinstated 2 fairway bunkers across the lake to entice a drive across the hazard.

The 15th green was moved straight back 30 yards onto a small peninsula of land previously providing a backdrop of trees. I felt the hole could use the additional yardage with firmer fairways going from 440 to 470 yard par 4. The new greensite and clearing has added a dramatic element to the finishing holes, now the player upon reaching the 15th landing area has a panoramic view of the entire finish of the golf course.

The 16th green was lowered around 2 feet, enlarged with a subtle Redan shape and angle restored as evident on the Maples drawing. A new tee was added tipping the hole at 238 with a low profile green feeding directly off fairway grade.

19. Some golfers consider the awkward 18th as a bit of a letdown. How do you respond to that?

The 18th hole is one of the most talked about and asked about holes on the Dogwood course. I doubt the work I did will resolve every issue someone had with the hole, but I think it is a much more interesting and challenging hole now. I was asked to strengthen the hole in a manner that the average player could handle and the better player would find interesting.

Being confined with water along the left and private property on the right, there is only so much you can do. I spent a great deal of time studying the 18th, so much so, that the club president upon seeing me lingering around in the fairway once again, reminded me there were 17 other holes I should also look at. From tee to green the routing changed very little, the tees were shifted left hard against the lake and I eliminated the blind spot between the tee shot and landing area right of the lake. The lake bank left of the landing area was shifted right adding 10 yards to the playing distance. The old fairway bunker parallel to the landing area was repositioned toward the end of the driving zone at 285 yards creating a narrow gap between lake and bunkers. This expanded the right side of the fairway and allowed integration of the hill working into the fairway from the right. Looking from the first landing area toward the green, a long cross bunker was added half way up the slope @ 100 yards from the green. The green turned on a stronger right to left angle thus requiring a full carry along the left side or a right to left drawing shot to run on. The old pot bunker directly in front was shifted to the right edge of the approach to entice more aggressive attempts in 2 shots (My original plan was to move the green back and left about 25 yards bringing the hole length to 535, we were no allowed to remove the tree due to woodpecker habitat).

My thought process and strategic thinking on the hole: By exposing the lake in full view from the tee, the player is inclined to play farther right thus adding length. The farther right you play, the sloping fairway from right to left comes more into play impacting the lie and long fairway metal second shot. The second shot is severely uphill and needs to clear the cross bunker or be left with a demanding 100 yard bunker shot. The player has options to consider, the option of playing short, to the right or to carry the bunker. Opening the approach encourages a more aggressive attempt at the green in two resulting in shots going long and into a very difficult up and down situation. This proved true during the recent Southern Am.

It was not my intent to try and make the hole play a lot harder or become unbearable. Instead, my primary goal was to make it more interesting for every player, retain the possibility of finishing your round with a birdie or an eagle but only if playing well struck golf shots.

20. You are currently working on Blowing Rock Country Club incorporating design features used by Seth Raynor. How much Raynor work exists there versus your plans?

The Raynor connection was confirmed through the efforts of the late George Bahto. I suspected it to be Raynor’s work based on several of the green features but had no evidence to prove it to a club that wanted and believed their course was designed by Ross. I received an email from George asking if I knew of a course in or near Blowing Rock called Green Park Norwood Golf Course. He indicated he had notes and information of Raynor having designed the course. I told him the old Green Park Hotel sits directly behind the 4th green at Blowing Rock CC. That was a defining moment in what will become the only North Carolina course by Seth Raynor, one that I feel confident will be one of the most talked about and discussed courses on the mountain.

Our research did not turn up any Raynor plans. Therefore, we are relying on old aerial photographs and the remaining features that were undisturbed during past renovations. It appears Raynor did not do any fairway bunkers and focused instead on the green sites. There was an old rudimentary golf course on the site prior to Raynor, so he remodeled the routing. We were able to identify several template green sites, Redan #2, Alps #3, Double Plateau #4, Hogsback (abandoned #6), Eden (abandoned #7), Punchbowl #8, Cape #9, Prized Dogleg #14 and Short #15.

Original Raynor holes 5 thru 8 have been abandoned but still remain in existence across the highway and behind the old hotel. Greens had been redesigned on what are now holes 5, 6, 10, 11, 12, 13, 17 and 18. We just completed remodeling holes 10 thru 13 back to Raynor style holes (these were not original Raynor holes), featuring a new Eden #10 (pictured below), Lion’s Mouth #11, #12 & 13 are non-template but with template references. We also restored the Redan on hole #2.

21. You recently traveled to Scotland, tells us something about your trip. Was it a typical Open rota trip or did you play anything off the beaten path that you found educational?

I visited Scotland in early June with my bother in law and two nephews, all good players. It was my nephews first trip over so it was exciting to see them experience links golf for the first time. We did play a few better known courses including the Old Course (my fourth round) and Carnoustie (my third round). I intentionally set up the trip to play some lesser known courses and decided to focus our trip in the East Lothian area. I’ve played the west coast and the Highlands two other times so I was excited to experience a new area.

One thing in particular I wanted to accomplish on this trip was to study the undulations through the approach areas leading into and through the greens. I have a potential project in the works here in the States that I want to incorporate such small undulations and nuisances. We played the Old Course in heavy rain and a strong trailing wind going out which brought the undulations fronting the early holes into play on every approach. Most of the flags were in the front sections requiring your approach to run on and feed through these magnificent contours. It was a profound experience even though I had played the course multiple times. The precision to hit just the right flat area to get the proper forward bounce was highlighted by the winds and firm conditions.

We played 8 courses on the trip, walked 2 others with three lesser known courses standing out in regards to variety and great architecture. The three that stood out for me were Lundin Links, North Berwick and Dunbar. All three had an abundance of variety and some quirky holes with rolling knobby irregular approach contours that I found particularly interesting. We flew into Edinburgh and played Lundin Links our first day, the course was a very pleasant surprise. Lundin has good variety, some surprising elevation in a few spots and some great contour leading into and through the green sites.

The course that absolutely blew me away was North Berwick – it stood above the rest in terms of sheer variety of holes and was an inspirational experience. Berwick has it all, blind approaches to punchbowl greens, greens tucked over stone walls, the most confounding green (#16 Biarritz style green) I have experienced (see below), the original Redan 15th and enough room off of most tee shots to get it around with only a ball or two.

We played Berwick in a steady 35 mph wind in our face going out, the first 7 holes were a bear, however the course settles down and gives you a chance to recover before turning back home. The finish is reminiscent of the Old Course coming back into town sharing the 18th and 1st fairways to a green at the base of the clubhouse fronted by a “Valley of Sin.”

The other course that grabbed my attention was Dunbar, I could play it the rest of my life and never tire of it. Very unique routing with the first 3 holes (5, 5, 3) going out and back to the clubhouse before heading up the coast away from town, before turning back after the 10th. One aspect of Dunbar I really enjoyed was the shared fairways and the option of choosing multiple lines off the tees with long irons, fairway woods and driver. The routing squeezes 2 holes into the width of a hole and a half on several sections, the option of using either fairway with a sliver of rough between was fun. The holes that stood out were the 8th and 13th featuring blind punchbowl green sites, the 10th a 2 bill 3 par with Redan playing characteristics. Also 11, 12, 14 and 15 are all strong 4 pars played along the coast back toward town.

We finished our trip with 9 holes of hickory golf inside the horse track at Old Musselburgh Links, not the most inspiring architecture but a fitting end to a great trip.