Feature Interview with Keith Cutten

February, 2019

Keith Cutten is a golf course architect and author. After starting on a shovel and rake in 2007 at Sagebrush Golf and Sporting Club, he has spent more than a decade working alongside (his mentor) Rod Whitman. Keith has participated in the construction of several of Canada’s highest-profile, contemporary golf course projects, including Cabot Links and Cabot Cliffs. Again with Rod, Keith completed the renovation of the historic Canadian Algonquin Golf Course in St Andrews-by-the-Sea, New Brunswick this past spring. In addition to his experience in the design and construction of golf courses, Keith has also achieved academic success. He gained an undergraduate degree in Planning and Environmental Design from the University of Waterloo, which led to a stamp as a Professional Planner. Additionally, Keith holds a masters degree in Landscape Architecture from the University of Guelph. More specifically, Keith’s masters thesis research explored the voluminous history of golf course architecture; which greatly assisted when laying the foundations for his new book – The Evolution of Golf Course Design. Keith serves on the Board of Directors for the Stanley Thompson Society and lives in Cambridge, Ontario, Canada with his wife and three children. Copies of his book can be purchased on his website here (https://cuttengolf.com/the_evolution_of_golf_course_design/).

1. Why undertake the five year creation of The Evolution of Golf Course Design? Was there a particular void you were trying to fill?

The research for the book actually started as a thesis, a requirement in my pursuit of a Masters of Landscape Architecture degree from the University of Guelph. After the major years of construction at Cabot Links in Inverness, and having worked with Rod Whitman since 2007 at Sagebrush, I decided to return to school as a mature student in 2012. The recession had made me realize that the golf industry, specifically the profession of golf course design, was getting smaller and more competitive. I wanted to do something to set myself apart.

However, I did not start the thesis process with the intent of turning the results into a book. Instead, my research was simply the product of trying to answer my own questions as they pertained to the history of golf course architecture. In fact, and also commencing in 2012, it was the restoration of Pinehurst No. 2 which started the ball rolling.

After hearing Bill Coore and Ben Crenshaw declare that they were ‘not environmental crusaders’ but simply wished to ‘restore the classic course to its intended design’, I began to ask myself how these changes could have been allowed to occur to such a masterpiece. Further, while sitting in a first year history course, I began to process the many events and external influences which would shape the top practitioners and history of landscape architecture. To me, having also taken similar courses in my undergrad in Planning and Environmental Design, the connections were both fascinating and revealing. Moreover, I was quick to realise that this method of study would be essential to our later success as landscape architects. As such, I began to ask myself why the study of golf course architecture had not been undertaken in such a manner.

Following a detailed review of the literature of golf course architecture, a journey which really started for me at the age of fourteen, I set to work to fill in the blanks. I decided to look at each designer with fresh eyes. Instead of fixating on their ultimate design philosophies and portfolio of work, I aimed to distill their influences and development as an artist. The effects of world history, economics, prevailing artistic trends, social movements, and the inter-personal relationships were illuminated and contrasted to reveal a more complete history. The resulting chronology and profiles revealed a deeper understanding of the profession. An understanding which I believe has made me a better architect in this age of renovations and restorations.

Because I needed to submit my research to a committee comprised of landscape architects, my thesis had been written in a manner which was accessible to even the golf architecture novice. So, when my degree was complete, I began to wonder if the golf industry would enjoy my findings. After contacting my friend Paul Daley, the Australian writer, editor and publisher, we soon decided it was a worthy project. We would spend the better part of the next two years polishing my research into The Evolution of Golf Course Design.

2. How did being an architect shape how you went about the task? Most writers are just that – writers! Some are researchers and they turn to writing to share what they have found but you are first and foremost a golf course architect.

Since 2008, the primary focus of the industry has been renovations and restorations. Thankfully, my mentors instilled in me a great respect for the history of golf course architecture and for those who, through their pioneering talents, helped to craft the incredible playgrounds on which I get to work. In order to complete a sensitive restoration, a designer must place their own influences aside and be able to step inside the mind of the original designer (or various designers, over time).

Similarly, working as a shaper on numerous new build projects, I have often forced myself to look at my work through the eyes of my mentors. Regardless of whether these project were under the direction of Rod Whitman, Bill Coore, Dave Axland or Jeff Mingay, it was important that my efforts complimented the project as a whole. As a result of this mentoring, I believe I was ultra-sensitive to these types of relationships during my research. Indeed, the importance of mentorship as a design influence is a key thread within the book.

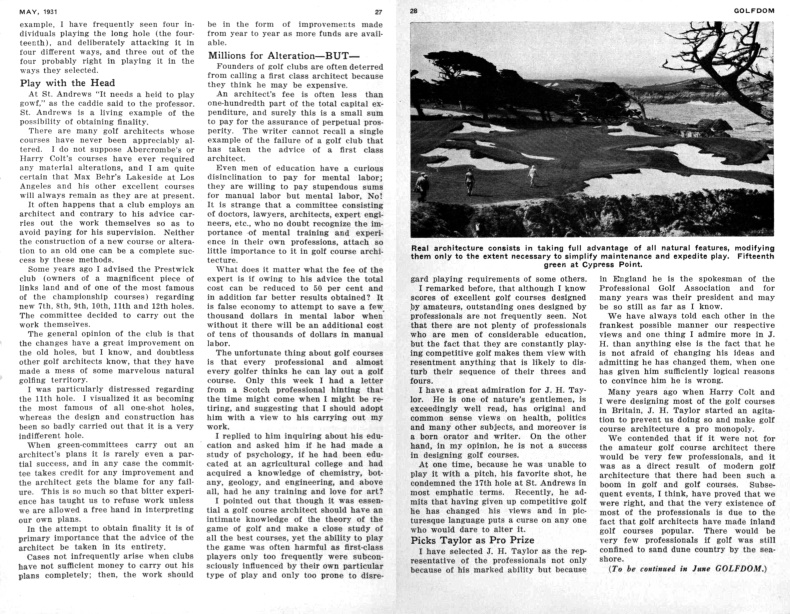

Further, I believe the link between literary production and professional practice has been overlooked. At the high points of design, the architects themselves acted as the curators of the knowledge pertaining to their craft. Designers like Walter Travis, Albert Warren Tillinghast, Max Behr, Robert Hunter and Tom Simpson all contributed frequently to prominent publications. Moreover, some of these men even acted as the editors!

The most important factors were the transparency and accessibility of this information. New ideas were debated in the public arena, whereby the most thoughtful arguments would prevail. The biggest benefactor was the game itself.

Today, we see a similar blurring of the lines between the golfing media and the profession of golf course architecture. Tom Doak has done tremendous work in this field. Geoffrey Shackelford has come from the other side, but has also dabbled in design while working to expand our golfing knowledge. While there are numerous other examples from both past and present, it is my belief that the art form is strengthened when the practitioners concern themselves with its history. Furthermore, I believe it is our duty to educate both ourselves and the golfing masses, all in an effort to strengthen the game.

3. You note in the Preface that “Whereas the ‘what-and-when’ of golf course architecture has been well-documented, the ‘how-and-why’ has lagged.” Please expound on that.

The benefits of this research stemming from my thesis, is the reality that the ‘need’ for my research topic had to be proven through the completion of a detailed literature review aimed at determining gaps in the existing knowledge. From this review, I determined that in excess of 15,000 books, and many more articles, have been written on golf’s vast subject-matter. Typically, the topics most heavily scrutinised involve those pertaining to the playing/teaching aspects, the game’s greatest players, the sport’s rich history, its equipment, to name a few. However, comparatively little has been written on the subject of golf course architecture.

Further, of those publications focused on golf course design, much has concentrated on maintenance and individual course designs. While literature in the field of golf course architecture has existed since 1888, this work has been frequently limited to individual architects, their design principles, and their portfolios of work. Essentially, we have unconsciously divided the study of golf course architecture into silos, whereby individual architects (and their portfolios of work) have become the macro unit of analysis. My research aimed to broaden this view and deepen our understanding of the ‘how-and-why’. As I stated previously, I believe that by analysing the effects of world history, economics, prevailing artistic trends, social movements, and the inter-personal relationships of the industry’s most influential practitioners, I was able to reveal a more complete history.

4. You tie equipment to the change in design. What are the three biggest changes in equipment since the game’s origins?

As you didn’t specifically reference playing equipment, I will use this opportunity to highlight the biggest equipment changes in three main areas – playing equipment, operations, and maintenance.

Early on, the formalized golf course, as we know it today, did not exist. Match play was the order of the day and was played in various locations on however many holes there happened to be. The equipment and playing techniques of the early players became tailored to courses, which suited low-trajectory shots. Linksland provided the ideal playground, where the conducive, free-draining soils, undulating topography, naturally occurring hazards, and ever-present winds, advanced the original strategy and challenge of the game.

Of all the various changes and modifications of playing equipment, the changes and modifications to the golf ball have had the most impact on golf course design. The early balls were wooden, and as long as this was the case, the game changed very little. In the early 1600s the feathery was introduced. These balls were able to travel higher and farther than wooden balls. In the mid-1800s, gutta-percha began being molded into golf balls. These cheaper, more durable balls began to be favored by the thrifty Scots. This ball became very hard, and wooden clubs began to be replaced by iron-headed clubs.

In 1898, Coburn Haskell made a discovery when he wound a rubber thread into a ball and it bounced. The process of making the rubber Haskell golf ball evolved over the years, but typically involved a round core which was wound with a layer of rubber thread. This core was then covered by a thin outer shell made of balata sap. In the mid-1960s, new synthetic resins were introduced (along with urethane blends) which provided a more durable cover. Golf balls began to be classified by how many components were used in the layering and construction process (i.e. 2-piece, 3-piece, 4-piece, etc.). The modern Pro V1 is simply the latest in this layering evolution, one which has allowed manufacturers to create golf balls with different properties. Today, some balls can fly farther, while others have been designed to generate more spin.

Recently, the profession of golf course architecture has begun to voice concerns over the golf ball and its impacts on the game, specifically the alteration of our classic layouts in a bid to keep them ‘relevant’. The most interesting facet about this whole debate might be the common misconception that this is a new problem. In fact, the great architects of the Golden Age encountered these same issues with the invention of the dimpled golf ball and steel shafts. Architects such as Max Behr, Albert Warren Tillinghast, Robert Hunter, Alister MacKenzie, Harry Colt and George Thomas Jr. wrote about the changes they were seeing in the game and a different vision being crafted in North America versus that which had evolved in Scotland. These architects believed the game was being diluted from its ‘sportier’ heritage into a game of exact distances.

Their writings and courses employed timeless strategies to mitigate the effects of technology on the game. Strategic design (angles of play) and width, combined with thoughtful ground contouring, was the prescription of the day, intended to stunt the effects of technology. More importantly, this method of design was intended to challenge the best players, yet allow the beginner to still navigate his/her way around the course. These designers understood that their job could be distilled to one mission – doing that which was best for the game. Golf is, after all, a game, and the best designers understand that it is their job to make it fun.

Unfortunately, following WWII and the Great Depression, this progression of knowledge was interrupted and the prevailing mindset changed as architects began to narrow fairways, grow rough, and eventually soften contouring (especially in greens). These wide sweeping changes were influenced heavily by other modern advancements, most notably, maintenance equipment. Developments in irrigation technology would alter the game for many decades. Whereas the greens were typically the only area irrigated prior to the 1950s, soon firm and fast conditions (which highlighted the playing impact of natural or created contouring) were replaced with lush green turf. The modern golf ball was adapted to fly higher, and golf course architects tried to reinvent the wheel in a war where the parameters continued to change from year to year.

Since the early 1990s, a renaissance of sorts has been occurring. Architects, dubbed ‘minimalists’ by the media, have begun to reintroduce classic design principles and construction methods. This shift has been aided by both the proliferation of information (via the internet and social media) and a general paralleling of social tastes. However, today we as architects are confronted with a difficult situation, and it has to do with length versus width and the economy of golf. Though steps are being taken to promote the environmental and economic benefits of firm and fast conditions, not to mention the benefits for all levels of golfers, the golf ball is still going too far. More importantly, the industry has been muzzled by the equipment manufacturers who fund both the media and the players.

The most important role of the profession of golf course architecture moving forward will be education. The correct application of classic design principles, and the responsibility to uphold that which is in the best interest of the game, must be our primary objectives. The golf cart, for instance, is another example of a monetary-based, operations decision which has negatively impacted the health and social aspects of the game.

We all love this game, and we must do that which protects its future.

5. There are two parts to the book. Part One is The Evolution of Golf Course Design, broken into twenty-one chapters and Part Two are profiles on architects, authors and visionaries. Let’s tackle Part One where essentially each decade starting from 1830 through 2010 gets its own chapter after the origins of the game. Is there a decade from 1830 to 2010 that you feel has perhaps been shortchanged (i.e. where more was accomplished than people understand)?

Though this period stretches for more than a decade, the importance of the work done by those operating between 1900 and 1914 (the onset of WWI) has frequently been undervalued when compared to the inter-war period (the Golden Age of Golf Course Design). After all, golf architecture as a profession was established in Britain. The decimation of the British economy and population following WWI prompted the movement of many to North America. Golf architecture’s pre-war practitioners made the move in an effort to exploit the budding markets across the Atlantic. However, the accomplishments achieved prior to the great wars set standards which last to this day. Further, it was the relationships between those challenging the conventions of the day which would change the industry.

In 1898, Horace G Hutchinson was instrumental in establishing The Oxford and Cambridge Golfing Society, commonly referred to as The Society. Interestingly, Hutchinson served as its first president, while John Low, his good friend, filled the role of captain. Arthur Croome was secretary, with Harry Colt a committee member. Bernard Darwin played in the first match, following The Society’s establishment. These relationships, formed between Hutchinson and the other members of The Society, have been largely taken for granted in the history of golf course architecture. In fact, these men took their relationships to the R&A, serving on multiple committees.

Moreover, the impact that Low, Colt and Darwin made on golf course architecture in the 1900s cannot be understated. Low’s efforts at Woking, Colt at Sunningdale, and Darwin with his pen, all worked to further the profession and deepen our understanding of golf course architecture.

If I am every crazy enough to write another book, I would love to devote more time into exploring this important era.

6. Horace Hutchison was both a formidable player and writer. Add the two talents together, and you credit him with being the primary voice for both the sport and golf course architecture in the 1890s. You also delve into his intellectual curiosities which included painting and sculpture. Tell us about his mentor George Frederic Watts and the Symbolist Movement and how they influenced Hutchison’s view on architecture.

In the early part of the 20th century, Horace Hutchinson’s playing history, social status, and his role with Country Life magazine, commanded great respect throughout the golf world. However, the influences which would shape Hutchinson, and golf course architecture as we know it, would begin to form much earlier.

In Britain, the damaging effects of machine-dominated production on both social conditions and the quality of manufactured goods had been recognised since around 1840. But it was not until the 1860s and 1870s that new approaches in architecture and design were championed in an attempt to correct the problems of the Industrial Revolution. The Arts and Crafts movement in Britain was borne out of an increasing understanding that society needed to adopt a different set of priorities.

In 1890, with his sixth-place finish at Prestwick, Horace Hutchinson achieved a career-best performance in the Open Championship. He capitalised on this success, and later that year released Golf: arguably, his most successful publication. Feeling fulfilled with his accomplishments in golf, Hutchinson acted as most socialites did at the time: he selected a new, exciting hobby to captivate his attentions. Hence, in 1890, Hutchinson moved to the booming metropolis of London where he began a serious study in painting and sculpture.

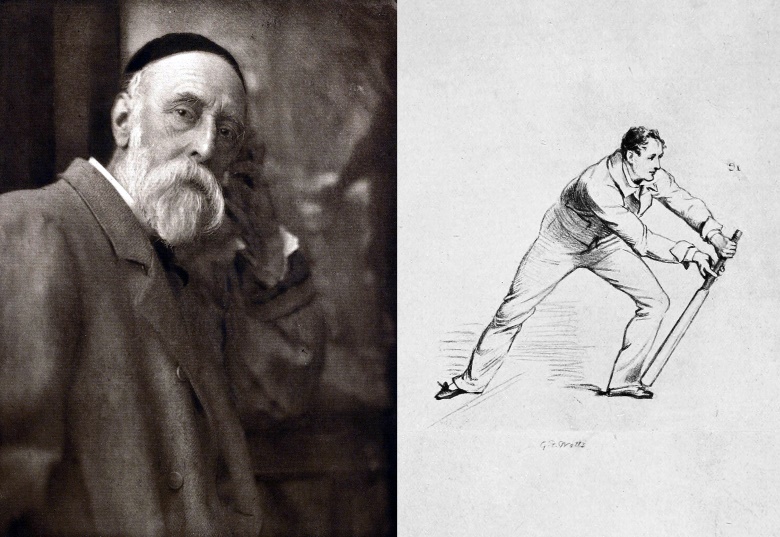

For the next year Hutchinson was mentored by George Frederic Watts, a renowned and popular English artist. However, unlike most other artists of his age, Watts was multi-disciplinary and worked as both a painter and a sculpture. Watts spearheaded the Symbolist Movement in Britain, which used mythological and dream-based imagery to convey deeper meanings than what was being expressed through the Victorian aesthetic; which was largely one-dimensional. Watts’ associations with John Ruskin, the pre-Raphaelites, and William Morris, all worked to further the Arts and Crafts movement in Britain. In fact, Watts even married Mary Seton Watts (nee Mary Seton Fraser Tytler), a Scottish craftswoman, designer and social reformer. The pair was well-established in their London studio when, in 1890, Horace Hutchinson began his studies.

However, due to a recurring illness which plagued Hutchinson his entire life, his studies under the great GF Watts lasted just one year. Notwithstanding, this education would have a lasting effect on the prominent golfer, writer and golf course designer. This connection is made more tangible when one considers two publications by Horace Hutchinson, which, due to their non-golfing subject-matter, have been largely forgotten by the world of golf.

The first of these literary endeavours was simply titled Cricket. Published in 1903, the book represents a series of essays on the bat-and-ball game, edited by Hutchinson. Although a handful of references pertain to golf, the most important connection is between the illustrations found in this later text and those found in Hutchinson’s first book, Hints on Golf. Whereas crude stick figures are used to depict proper golf swing positions in Hints on Golf, Hutchinson employs the skills of his mentor GF Watts to provide seven wonderful drawings within Cricket; which show the cricketers in the various positions of defence or attack. This revelation is important, because it shows that this mentor-protégée relationship was not fleeting. In fact, it lasted at least a decade. More importantly, the connection lasted into the early 1900s: a period when golf course architecture irrevocably changed; and Horace Hutchinson was the person helping to plot the course.

Then, in 1920, Hutchinson penned his last publication: Portraits of the Eighties, in which he acknowledged the work of George Watts, William Morris and the pre-Raphaelites. Hutchinson even describes his own ‘Watts-worship’, in a story relating an event at Tate Britain (Gallery) of London. Further, he articulates that posterity is funny and no one can ever predict how time will judge them; but proceeds to declare that Watts will ‘rank with the immortals.’

Clearly, Horace Hutchinson was fascinated by Watts. More so, his respect for the artistic ideals starting with Watts, and extending through the pre-Raphaelites and the Arts and Crafts leaders into British society, remained with him late into his career. Crucially, he soon imported this reality back into the world of golf.

In 1892, Hutchinson created his most celebrated golf course: Royal West Norfolk, often referred to as Brancaster. Suitably proud of the achievement, he observed ‘its distinguished features are the absence of artificiality and there is great variety to be found in the holes.’

Five years later, in 1897, Hutchinson took up his post as inaugural golf editor of Country Life. From this position, Hutchinson would use his literary soapbox to direct the next two decades of golf course architecture in Britain.

7. The Morris and Park families are well-heralded, but you make sure the Dunn family gets its fair credit too. For instance, I was shocked to read that Tom Dunn is credited with 137 courses, many of which were essentially fields (often times not on great soil) upon which to play golf. From a design perspective, is there much to be gleaned from studying his work?

Yes, there is much to be learned. Courses such as Broadstone and Woking surely illustrate his talents. While I recognise that others polished many of his best-regarded courses, he undoubtedly conceived their general structure.

To quote Horace Hutchinson in defence of Tom Dunn: ‘A man is not to be criticised because he is not in advance of his time.” I also take this to mean that a golf course architect is a product of their time (and the influences which lead to their own personal evolution).

Bill Coore once told me that he learns more from seeing a bad golf course than a good one. I think the same can be said for those who study history. Understanding what not to do, and more importantly why, can bring about greater understanding when compared to simple success stories. The study of golf course architecture should be considered in the same way.

Today, we hear many voices downplaying the work completed by golf course architects between the early 1960s and late 1980s. Yet, at the same time, we praise ourselves as members of some sort of ‘second golden age’. More study needs to be completed so that we truly understand this history. I know my book has only started the ball rolling. Such work assumes importance on another front, too, for when the current framework of social and economic influences changes, as it inevitably will, only a clear vision of the past can inform decision-making surrounding this game we love.

8. The book is beautifully illustrated with many diagrams and photographs I have never seen before. One broke my heart: the picture of the burn at Carnoustie circa 1880s that is much wider, far more handsome and interesting than what exists today. Is that the peril of a waterway (i.e. that at some point in time, it becomes more about function than form)?

Firstly, thank you. Paul and I spent more than three months, poring over thousands of images and plans, in an effort to select those which would bring the words to life. We are truly proud of the book, and the initial feedback from people has been incredible.

Due to the support of people like Dale Concannon, Jon Cavalier, Evan Schiller, Gary Lisbon, Simon Haines and Ron Whitten, we were able to secure some spectacular imagery, spanning some 250 years. I also scoured the archives in Guelph (Stanley Thompson), North Carolina (Tufts) and Massachusetts (Frederick Law Olmsted) to source some incredible plans. In total, the book has more than 300 images and plans, showcasing architectural efforts from all over the world.

I agree, the Carnoustie image is truly exceptional. Not only does it show the inclusivity of the game at that time (with the young boys playing golf), but it also shows the more rugged and natural look of this famous Open venue. Though I am not an expert on Carnoustie per se, I would hedge my bet that this burn has endured the same social pressures as most other golf course features following WWII. As modernism became a global phenomenon, man’s desire and ability to control nature permeated all forms of landscape design and architecture. The burn is likely a casualty of such an evolution.

9. From which decade do your own personal favorite courses emerge?

The decade in which my favourite courses emerged was the 1900s (technically 1903 to 1913). Likely because my father and grandfather are English, and they both heavily influenced me to become a golf course architect, the Heathland courses of England hold a special place in my heart. In fact, during my undergrad I did a two month exchange in Oxford to explore this area. My experiences at Sunningdale, St. George’s Hill, Swinley Forest and Woking have been seared into my memory.

… Of course, as a Canadian, it is very difficult for me to not recognize the incredible work of Stanley Thompson in the 1920s and 1930s. In fact, it was his work at Westmount Golf and Country Club in Kitchener which first blew my golf course architecture mind. I worked on the grounds crew there during my undergrad at the University of Waterloo. I find it interesting that Stanley Thompson was clearly influenced by Harry Colt’s work at Toronto and Hamilton.

10. Why do you reckon that those courses resonate more with you than courses from the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s?

This may be simplification of events, but I believe it was due to the motives of the designers and owners. Prior to WWII, the focus of the golf course designer was on crafting distinctive courses that reflected an accrued knowledge pertaining to what would produce great golf. There is a sense of place found at earlier courses which doesn’t exist at those produced during the later decades in question. As this focus shifted, architects began to emulate the latest trends, all in an effort to produce marketable golf. Design became a business, one which was good for certain people, but not the game itself. The architect-contractor model was a result of this business minded approach. I am a firm believer that the results are best when the artists wields the paintbrush. In the case of golf course architecture, this means the architect must be onsite and active in the construction process.

Feature Interview with Keith Cutten pg ii

11. From all your research, what is an underappreciated fact of golf course design from the 19th century? 20th century? 21st century?

19th century – Just how prevalent Victorian golf course design principles were in the world of golf course architecture. Further, this design methodology was not simply contained within Britain. In fact, Donald Ross’s early work at Pinehurst involved chocolate drops, forced carries over penal hazards, and square greens. While evidence of this is presented in Bradley Klein’s wonderful book Discovering Donald Ross, which also shows similar ideology in his work at Oakley Country Club (plan on page 46), common thinking describes Donald Ross as the bringer of change. By this, I mean that he removed the Victorian elements for strategic ones based on his time at Dornoch and mentorship by Old Tom Morris. However, as seen in the following 1910 plan of Pinehurst No. 2, the layout still shows many Victorian features including square greens and forced carries over fields of chocolate drops. Indeed, Ross underwent his own evolution as a designer in North America, slowly becoming the incredible architect we know today.

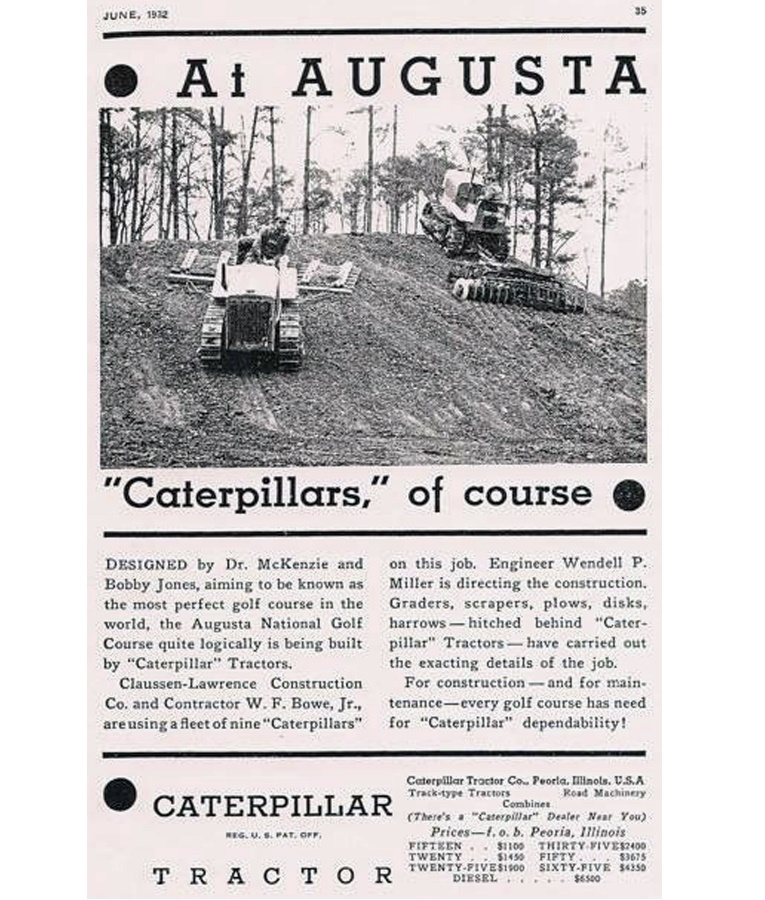

20th century – The overwhelming influence that Modernism had on all facets of life following WWII. Today people frequently blame advancements in construction equipment or residential development for altering the traditional values of golf course architecture. However, prior to the Great Depression heavy equipment was being used in the construction of golf courses. Projects like the Lido set new standards for what was achievable given modern advancements. In fact, even Augusta National was originally shaped with more efficient tractors/bulldozers.

However, the products were still based on classic design principles, implemented by designers who were present during the construction process (or utilized skilled construction foreman). Furthermore, numerous Golden Age projects were devised as part of a larger residential communities – Fisher’s Island, Capilano, and Garden City, for example.

The sweeping changes following WWII were driven by a social desire to look forward. Following the fifteen year period which included the Great Depression and WWII, a war which was much closer to home for most than WWI, people began to focus on the future. Although WWII concluded in 1945, its effects shaped the global ethos for decades.

In America, much of the pre-war immigrant diversity began to dissolve, arising from the standardisation of tastes and language infiltrating the American mainstream. Whereas first- and second-generation immigrants accounted for roughly one-third of the American population between 1900 and 1935, this number steadily decreased following the war years; culminating, in 1965, in an all-time low of eighteen per cent. As families began moving from farms and cities into new suburbs, American culture underwent a major transformation and homogenisation. Longer distances between home and work sparked a highway and housing construction boom. Race and class dynamics began to shift, as older community institutions began to disappear and be replaced with images of the American family. The baby boom was just one result of a new movement that had much of the Western world looking forward. Innovation, not tradition, became the predominant social ethos.

21st century – Recently, experts have acknowledged that we are likely experiencing some form of Renaissance, or a Second Golden Age of Golf Course Design (also dubbed Neo-Classical). However, what we have failed to recognised is the reasons why. Again, it comes down to external influences directing the profession of golf course architecture.

By the end of the 2000s, world trade had quadrupled since the early 1980s. Although the world remained as interconnected as ever—through telecommunications, the arts, culture and (most importantly) the Internet—the Great Recession caused massive changes in social perceptions. In the decades prior, the Western world had seen the exportation of its manufacturing sectors, in favour of a more services based economy. Globalisation allowed for an unprecedented worldwide mobility to goods, services, investment and labour. Hence, countries relied more heavily on each other; a condition not supported by the bursting of a global economic bubble.

Western governments, through bailout initiatives and growing nationalisation, began to exert profound new influence over banks and international corporations. This placed a spotlight on the effects of globalisation of the world economy. The new message being delivered was that there was ‘no place like home’ for job creation and investment.

In North America, these global patterns resulted in an anti-big box consumerism craze, which has been dubbed the Shop Local Movement. Similar to the social shifts resulting from the Industrial Revolution in Britain prior to the First World War, ongoing deglobalisation has spurred public interest in handmade, high quality, and locally sourced products. Markets include food and produce, art and furniture, and even golf course architecture. The emergence of income generated by Xennials and Millennials (Generation Y) into the global markets has revealed a willingness to pay more and travel further for authenticity and quality. We see this directly in the visionary work of the Keiser family.

The developer-driven model was failing; however, the minimalist movement, which was founded on the design-build method, continued to persevere. This movement was only strengthened by the global economic instabilities, as the surfacing craft-styled approach (design-build method) is capable of surviving on an annual output of just one or two projects. The reason is simple enough: a deeper involvement of the designer. This approach is in stark contrast to the architect-contractor model, which had permeated the profession during the modern era of design.

12. Moving on to Part Two, you profile architects, authors and visionaries. The architect section is the most voluminous with well over 40 people profiled, followed by 12 authors and 5 visionaries. The architects and authors are scattered across the globe, but the visionaries are all from the United States. What macro-factors contributed to that being an all-American section?

Funnily enough, my research has actually revealed that much of the modern interpretations regarding the history of golf course architecture have been largely American-centric. As such, it was my goal to diversify the profiles to correct this misrepresentation. However, when it comes to those on the developer or member side who affected the history of golf course design, the resulting list of names is comprised of purely Americans. The reason for this is twofold.

Firstly, land rights in Britain, where the game originated, are vastly different than in North America. Less than a century and a half ago, all land in Britain was owned by 4.5 per cent of the population. The rest owned nothing at all. Today, 70 per cent of the population has a stake in land, and collectively owns most of the 5 per cent of the UK that is urban. However, this is a mere 3 million out of 60 million acres.

Back in 1870s, when Britain’s population was approximately 28 million, there were just over 3.84 million dwellings, of which 703,000 were privately owned. Between 1873 and 2010, the population multiplied by 2.2, but the number of houses jumped more than sevenfold. The number of privately owned houses increased to 18.6 million, a 26-fold increase, as the majority of the population moved from landless to landowning, and from a waged working class to an asset-owning democracy. Historically, this meant that individuals with the power to enact change were few and far between. Moreover, their interest in golf was, at most, a minor curiosity. As a result, many of Britain’s clubs were the result of the efforts of a group of founding members who would hire an expert. It was this expert who then developed a career and may be profiled in my book.

However, this history does not tell the full story. Part two of this equation is the external economic and social changes which shifted the hub of the golf architecture world from Britain to America following WWI. Significantly, this is still where it remains. In America, the land of opportunity, the ownership and availability of land was completely different. A person with a dream could more easily craft their future. It is the efforts of these Americans which have been profiled as ‘visionaries’, specifically because of their impact on the rest of the golfing world.

13. Rod Whitman is a hero of both of ours. What have you learned working with him and how do you think that shaped the content of the book?

I have been very lucky to call Rod Whitman a friend and mentor for the past 12 years. His dedication to this craft is second to none. In fact, my first lesson came on my very first day at Sagebrush, back in 2007.

Hired as a labourer, I spent most of that summer toiling in the bunkers, trying to contribute where I could to the design. On that first day, I watched from the massive, left-side fairway bunker as Rod spent 2 hours working to create the first green. When he was done, he walked his dozer back to the approach and stared at his creation for 20 to 30 minutes.

During that time, our bunker crew studied the contours of the green with great interest. We all agreed it was a work of art. Rod then climbed into his dozer, walked his machine back over to the green, and proceeded to destroy his creation. As inexperienced as I was then, I couldn’t begin to comprehend what I was seeing – the destruction of greatness. However, 1.5 hours later Rod had again finished. The completed green complex was even better and more interesting than the first rendition.

Then, again, Rod went back to the approach and began to study his work. Not only did he further rework parts of the green, but this process went on for an additional 3 or 4 hours. When all was said and done, the completed green had reached its ideal form. I knew right then and there that I had found the right guy to show me how to build golf courses. Furthermore, it would be this attention to detail which would rub off on me, aiding me greatly in the realisation of my own creative projects.

Rod’s loyalty and mentorship is something he takes very seriously. Rod pushes me daily to be better. Our relationship in the field is one that has evolved to have complimenting skillsets. I believe this shows in our work.

Rod’s second biggest impact on the book was in helping me to better understand the mentor-protégée relationship. Rod started his career in golf course architecture in 1980 after securing the position of construction foreman with Pete Dye at the Austin Country Club. However, this job offer came to be because of a recommendation by Bill Coore. Rod had been working on the grounds crew at the nearby Waterwood National Golf Club, under the management of course superintendent Bill Coore.

Rod has spent a career shaping his own projects, as well as working to better the projects of bigger names like Pete Dye and Bill Coore. However, it was the mentorship (and friendship) he gained through these associations which made him a better designer. While I am of course proud to be included in this ‘Dye family tree’, one which is currently restoring the fundamentals of great golf course design, it was the understanding of this history which prompted me to look for other such relationships. My findings really help to define the history of golf course architecture and, I believe, should be a model for the profession moving forward.

14. Is it safe to assume that your knowledge and appreciation of history increased during this immense undertaking?! If so, how will that increase in knowledge drive your work in the field on a go-forward basis?

Indeed it has. I have always loved the elegance of MacKenzie’s writings on the subject of golf course design. He often sighted the need for the designer to use their brains as their most valuable tool, saving a project both time and money. However, he also related this analogy to the site itself, and a designer’s ability to work with the land.

I think the same can be said for a historic golf course. Too often, owners or committees rush to start construction once a designer has been selected (often based on a great sales pitch). I feel it is the job of the golf course architect to use their intellect to represent their client’s needs. This process will involve acting as the historian, archeologist, environmental planner, engineer, hydrologist, superintendent, owner, club member and mediator. Information is power, and the more a designer has, the better his/her design decisions will be. I feel that my book, coupled to my education and professional experience, has given me the necessary skillset to assess these various needs.

15. The chapter on the decade 2020 has yet to be written! Please take your best stab as to what a) will emerge and b) what you hope will emerge.

As you can probably tell by my answers so far, I am a firm believer that efforts within the golf industry are directly affected by external influences. Currently, our world is very much in turmoil. Tensions in the United States, Britain and Europe threaten to destabilise both political and economic balances. The growing influence of Russia and China can no longer be ignored. After all, golf is a leisure activity, one which has typically thrived during periods of stability. In essence, investment in the game becomes much easier when prospects are high, so we best hope for a more stable future!

That said, there are many young, talented and passionate shapers/architects waiting eagerly in the wings. I believe the recent ‘thinning of the herd’ caused the Great Recession has put the golf industry in a prime position moving forward. When the market inevitably turns, I believe we will see those emerge who will continue to push the boundaries of strategy and aesthetic execution. Most importantly, I think there will be a strong push for local and urban golf, where accessibility to great golf will help to foster the game.

16. How did you determine the structure of the book?

The structure of the book came quite naturally due to the research methods used. Generally, the profiles were created first, as the influences of each person needed to be clearly understood before proceeding. Then, I created detailed timelines revealing patterns for the many external influences (economy, war, technology, allied art forms, etc.).

Typically, the text books I was using to define these trends grouped eras and movements by decade. This was especially prevalent with the study of world economies. As such, it only made sense to convey my own research in this manner. Further, I believe this decade-by-decade structure is much easier for most people to comprehend (versus unstructured timeframes).

The profiles at the back of the book are there for your average club member (or specific architect lover) who desires to know more about a specific practitioner. Further, the profiles allowed me to dive deeper into the background of these key influencers, revealing more detail regarding why they did what they did during their careers.

17. Did any awkward moments arise in the process of compiling the material?

Of course! Most interesting to me was the fact that those on the design-build side of the industry were much more accommodating to my research than those who practiced the traditional architect-contractor model. While this trend did have some notable outliers, my ability to contact those with big practices was made much more difficult due to their ‘gatekeepers’. I had to be much more persistent to obtain a response. This reality becomes more interesting due to the fact that because of ethics issues at the University of Guelph, I could not use my associations or background in golf to sway favour. Indeed, it was the architects themselves who chose whether to offer some transparency when it came to their design influences and philosophies.

18. Who would comprise your ideal foursome whereby you could pick their brains on architecture? Also, which course (!) would you elect to play with your dream foursome?!

To observe Harry Colt, Alister MacKenzie, John Low and Horace Hutchinson play a match at The Old Course would be the thing of dreams. I would be a fly on the wall as they debated all the changes which had been allowed to occur to that sacred ground. Further, I would make it a 54-hole match with part two played at Sand Hills and part three held at Cabot Links. To watch them play the poster child for minimalism – Sand Hills – would be a real treat. I would delight in the opportunity to pick their brains as to the intricacies of the design. I would also listen intently as they played Cabot Links. Imagine the wisdom I could gain having those brains analyze a project on which I contributed.

19. Who influenced you and gave you the courage to pursue going down the hard cover publication route?

My family has always been hugely supportive. I am lucky to have the family that I do, and a wife who sacrifices much to allow me to chase my dreams.

While I’ve always had the necessary support at home, Paul Daley was the one who held my hand through the publication process. His knowledge and skills in the literary fray went far in easing the stresses of this young writer.

20. As I scanned the index, one name stood out from all the titans: George Cumming. Tell us how he made it in while someone like Charles Banks hit the edit room floor.

Inclusion in the profiles was based on two factors: space and overall influence on the profession of golf course architecture. In the case of Charles Banks, his methods were simply an extension of those developed by his mentors – Charles Blair Macdonald and Seth Raynor. As such, and with a career which largely saw him complete the work of Raynor following his death, Banks’ portfolio didn’t move the needle the way the efforts of others did. Again, as I say in my book, this is not meant to detract from the quality of his work, it merely signifies that the work of those summarised in the profiles reveal a deeper appraisal of the evolution of golf course design.

For instance, George Cumming helped to pioneer golf course architecture in Canada. Born in Scotland, near Glasgow, Cumming immigrated to Canada in 1900. At the Toronto Golf Club, Cumming served the dual role as the club’s head golf profession and greenkeeper. In 1910, when the club decided to relocate properties, Cumming was tasked with sourcing the new site. While it is unknown the extent to which he contributed to the construction of the new Toronto Golf Club, a Harry Colt design, Cumming did take advantage of the other sites which he had found (which had not been used) to solicit his first design work.

Immediately after WWI, Cumming partnered his protégés: the brothers Nicol and Stanley Thompson. The firm was named Thompson, Cumming & Thompson, and it operated initially as a side business for the trio. Cumming still held the position of head professional at Toronto Golf Club, while Nicol served as the head professional at Hamilton Golf and Country Club (the other Colt course). Cumming’s mentorship of the Thompson brothers would set the framework for Stanley Thompson’s future successes.

21. Max Behr was quite cerebral, and his best designs were feature rich. As an architect, does it give you pause when you see such designs routinely fail to stand the test of time while ho-hum ones fare better?

Very much so.

For ages, people have debated the value of art. Should creativity be a vehicle for commerce, or something completely divorced from the marketplace? After all, doesn’t art need an audience? Is the perfection of one’s craft a noble pursuit, or an exercise in vanity? The truth is a little more complicated. While I have always agreed with MacKenzie’s notion that the best work is polarizing, in the end a client’s success is linked to the design decisions made by the architect. Yet, the more distinctive and creative the effort, the more likely it will captivate and demand an audience.

In his book How Buildings Learn, published in 1994, Stewart Brand explains how buildings adapt and evolve over time. Brand identifies three factors which often force buildings to change, they are: 1) technology; 2) money; and, 3) fashion. He claims that more than any other human artifact, buildings improve with time, if allowed to. He then asks the question, “how do buildings come to be loved?” He concludes that the simplest answer is age. However, to achieve a longstanding age, a design must survive. Brand proposes that in order to survive, the design must be able to adapt.

Brand stresses the value of an organic kind of design, which can be altered and expanded easily to evolve into a building’s ideal form. While looking back through architectural history, Brand found a point when architects began considering themselves artists causing a steady decline within the profession. What he dubbed “Magazine Architecture” resulted from this progression, as owners and designers cared more about the appearance and “wow factor” than the final purpose and function of the building itself. The long-term function and maintenance of the products of the design process are not the focus of the magazines and, as a result, are given a lower priority. Clearly, many similar relationships can be found within the evolution of golf course architecture.

Sadly, Behr’s work fell victim to change on two fronts: money and fashion. In California, the fifteen year period between the start of the Great Depression and the end of WWII would have resulted in immense changes to his courses, given the climate. Additionally, new ideas pertaining to golf course architecture, ones derived from both Modernism and a more economic conscience, would have precluded his courses from the restorations they deserved. Behr passed away in 1955, leaving only his writings to defend his work. Sadly, I believe we have analysed his words more in the past 15 years then the 50 years prior.

22. You write, “In 1898, Horace Hutchison helped to form the Oxford and Cambridge Golfing Society (OCGS) and served as the Society’s first president. Joining Hutchison, an impressive line-up was assembled: John Low (captain); Arthur Croome (secretary); and Harry Colt (committee member). Bernard Darwin took part in the first match.” Talk about a gathering of heavyweights! Did a more collaborative spirit exist back then among architects and authors than perhaps what does today? If so, I wonder the ramifications?

I do believe it did. However, I believe this collaborative spirit existed out of necessity. Whereas golf course architecture is viewed today as a noble profession (by some at least!), at that time golf architecture was simply a side venture for most professionals who sought to expand their equipment businesses. As educated men moved into golf course architecture, there grew a desire to mimic the prestige of their former professional careers. Indeed, partnering with like-minded people and working to expand the knowledge of your growing profession, most importantly under the public spotlight to generate interest, was the recipe for success.

Today, I believe this spirit is not lost, just reborn. It is alive and well in the current design-build methodology. Protégée architects advance to competent designers, creating teams where the sharing of ideas is helping to elevate projects to greater heights.