Feature Interview with Jonathan Cummings

July 2020

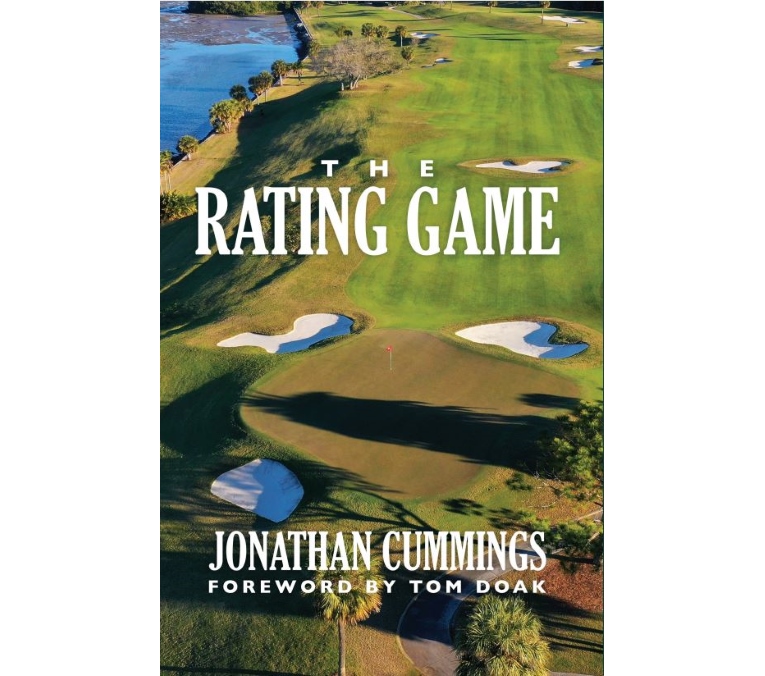

Jonathan Cummings spent 37 years as a research test & measurements mechanical engineer and currently is an anti-submarine warfare consultant for DARPA. Cummings has long been active in golf as a travel consultant, journalist, editor and speaker. For over 30 years he served as volunteer and/or committee chairman for the Kemper, Booz Allen, Quicken Loans, Constellation Energy and Tiger Woods Foundation PGA tournaments. He has also served as executive board member for JPC International Golf Academy. Cummings spent 19 years as a Mid-Atlantic course/slope rater and is a USGA rules and rater graduate. He is an original Golfweek panelist (1996) and past panelist for LINKS and GolfStyles. He has played golf in all 50 states and in 35 countries logging rounds at more than 1600 courses. A member of the USGA, Golf Writers Association of America, Donald Ross Society, Seth Raynor Society (board member), TPC Potomac and Belleair CC. Cummings lives in Belleair, FL and can be reached at golfguydz@aol.com. To order The Rating Game, please click here.

1. What inspired you to write The Rating Game?

I’ve had a curiosity about ratings and course lists for years. It started in the 1980s with a love of playing golf coupled with an insatiable travel bug. To feed these, my vacations took me to destinations around the country and the world and to golf courses I had never seen before. As an engineer, compulsive by both training and nature, I kept personal lists of the courses I have seen, adding comments and grades, and forever sorting them. By the 1990s I had seen enough golf courses (500 or so) to start writing a golf travel letter summarizing the courses I had seen over the past year.

Over time, I started to use the travel letters to write not just reviews of the new courses I had seen but also to explore some aspect of golf course ratings – history, interviews with notables, personal perspectives on course quality, etc. These letters (5 total, each 50 pages or so) launched my interest in ratings and became the genesis, inspiration and “first drafts” of The Rating Game.

2. Writing a book about magazine golf course ratings is certainly a very particular undertaking, one that has never been done before. What did you hope to gain from your (extensive!) effort?

Writing The Rating Game was self-serving to a degree. I’ve long been curious about the rating processes and I used the book as a vehicle to research and learn as much as I could about it. Over the past 40 years or so I’ve written many technical reports as well as several hundred golf articles. Writing a book, though, required a whole level of effort. It ended up being a huge undertaking, consuming quite a bit of time, but it was a challenge and something I’ve always wanted to do. It was also enormously rewarding on a personal level. The targeted audience or niche is small, so I was under no illusion that this was a money-making venture. But I liked writing for other folks who share the same – admittedly wacky – love of the technical aspects of the game.

3. What do you hope is the reader’s biggest takeaway from The Rating Game?

A couple of things. First, I hope the reader gets an appreciation that once you start putting numbers to golf course quality, there is a math factor that can’t be ignored. Processing numbers has rules. If you veer, gloss over or ignore these rules, you degrade the end product – your golf course rankings. The best rankings are ones that use no numbers, striving to capture, as much as possible, the merged subjective view of the panel.

I also hope reading the book increases a person’s curiosity and appreciation of the architectural aspects when playing a golf course. The time, money and effort put into making a quality layout is immense and underappreciated by many players who either don’t see or grasp land features that required much discussion and thought by architects and builders.

If one person tells me that after reading the book they see and appreciate a golf course more, I’ll be happy.

4. You did your homework on the history of ratings and the mechanics of the processes. Still, most people see ranking courses as a subjective exercise, so what can the reader glean from the more analytical/technical aspects of The Rating Game?

The subjective part of the rankings is what’s appealing. Tom Doak (and others) has always said that the most interesting list to him is an individual’s ranked list. The reason is simple – you can’t get any more subjective than a list from a single person. There’s no math, no manipulation, no objectivity – it’s all one person’s unvarnished opinion. You may argue “I can’t believe you like A over B, are you on drugs??” But what you can’t argue with is the way that person developed his list. It is purely subjective.

The author with the man who wrote the forward to The Rating Game, Tom Doak.

It would be nice if the magazine lists could do the same thing, but because they are generating composite lists (based on many people’s opinion), it’s tougher. They must rely on an intermediate step, one that uses numbers to first quantify a course ranking, then combine (average) those numbers in such a way as to generate a single set of course values that can be sorted and numerically ranked. It’s that intermediate step that screws us. With numbers come errors – rounding, resolution, bias and a host of others.

What I hope the reader gets out of the book’s analytic discussions are the importance of minimizing these errors to maximize the purely subjective part we are most interested in.

5. What can a publication do to gain a reader’s ‘trust’ with its particular list?

All three major US magazine lists are comprised of both subjective and objective data. The subjective part is the rater’s opinion (ratings) and the objective part is what manipulations a magazine does with those individual opinions to determine a ranked list. As discussed above, it’s the objective component we want to minimize and the subjective, maximize.

What can a magazine do to increase trust? First, be transparent. Report methods used to process the data. Consider reporting answers as ranges instead of absolute rankings (“our raters determined that course X is ranked between 45th and 65th within 90% confidence”). A magazine shouldn’t be afraid of reporting ties. It is disingenuous, at best, and data fraud at worst, to adhere rigidly to numerical ranks where scores are broken by the hundredths of a decimal place. These should be treated as ties. Use the example of ranked leader boards as applied to the PGA tour. Player A leads at 10 under. Tied for second place at 9 under are players B, C and D. Player E is next in fifth (not third) place at 6 under.

I also believe a magazine would improve trust in the lists by being open about who they use as panelists and how they monitor and manage those panelists. With less than 100 panelists, it’s easy for GOLF Magazine to list the panelists in their Best issues; it’s a little harder for GD with ~1,800 panelists and GW with ~800 to do the same. But as a reader, I would like to know what level of experience the people contributing to the list have. A list is only as good as the data being inputted and the more you can tell me about the data and its sources, the more confidence I’ll have in the list.

6. Fair enough. Discuss how ratings add to the golf course conversation.

Well, it both adds and subtracts.

Ranked lists from recognized or even unrecognized authorities provide a barometer to which we can compare our own lists. Ranking lists sometimes refreshes, sometimes reinforces, and sometimes stimulates us to reconsider our opinion on a certain course. This can be gratifying. A newly opened course that you rave about (or pan) to your friends may come out on various lists highly (or lowly) ranked, giving you some sense of correctly assessing the layout and predicting the sentiment of others. On the plus side, the cachet associated with a newly ranked course, can promote buzz and even be a potential financial boon for the club, commanding pricier greens fees, initiations, and dues.

There are minuses as well. Ranked lists can encourage a club to spend money, through course modifications and upgrades, to “increase” their rankings. There is no guarantee that such efforts will go as intended, which can leave the club poorer and may even see them slip in the rankings.

It would be nice if the magazine lists could do the same thing, but because they are generating composite lists (based on many people’s opinion), it’s tougher. They must rely on an intermediate step, one that uses numbers to first quantify a course ranking, then combine (average) those numbers in such a way as to generate a single set of course values that can be sorted and numerically ranked. It’s that intermediate step that screws us. With numbers come errors – rounding, resolution, bias and a host of others.

What I hope the reader gets out of the book’s analytic discussions are the importance of minimizing these errors to maximize the purely subjective part we are most interested in.

Jon Cummings (second from left) and Ran Morrissett (far right) at Casa de Campo, 2006.

7. Why are golf course ratings a ‘hot button’ issue?

There is little we are more passionate and surer about than our opinions. Two people can argue their different opinions until the cows come home, without ever reaching consensus. Each is positive he/she is right and the other is wrong. We are often so cemented in our views that it is incomprehensible to one how another could even have an alternate opinion. Look no further than politics as a good example. This certainly seems to be true with golf course lists as well, even more so than with, say, lists of best movies or restaurants.

More passionate reactions are particularly true with new golf course additions and courses with large moves up or down a list, which can generate near-violent agreement or disagreement. The courses at the top of the lists usually don’t generate much passion because they, for the most part, don’t move up or down much and are widely accepted as being ranked where they should be.

I’m not sure I can answer well why ranking discussions are often so heated. It may be that a traveling golfer invests a chunk of time and money seeking out a new golf course to which he generates a good or bad opinion. That opinion is stronger than an opinion he may have about a new movie or restaurant because of the degree of his personal investment. Or maybe, folks are more willing to concede that others could have different taste in movies, food, etc. than in golf courses. It’s interesting. Could it also be that folks think – wrongly maybe — that golf course ratings are more objective? Couched in number crunchings like the magazines publish, could it be that folks think golf course ratings are more “scientific” and more firm (especially when they coincide with their own opinions)?

8. Some panels make use of categories to either determine or help determine rankings. Please discuss the pluses and minuses of a category-based system.

The premise of a category-based system is straightforward – the relative “greatness” of a golf course can be broken down to sub ingredients, with those ingredients measured numerically and those numbers combined in such a way as to generate an overall score. Simple premise, although there is considerable argument as to its validity and application.

If a category system is to be considered for ranking courses, each category must pass two tests: is the proposed category meaningful and is it measurable? For example, golf course character would be a widely accepted subcategory of greatness, but character doesn’t lend itself well to numerical measurement. Outdoor temperature lends itself very well to being measured, but is, obviously, unrelated to determining course greatness.

The book addresses this topic by conducting a little test using correlations to calculate how useful a category might be. I used actual field data from mine and other GW raters for 100 or so golf courses. I used the GW categories (conditioning, walk-in-park, etc.) and determined correlation coefficients (degree of relationship) for each category against the overall rating, which was determined independently.

Here’s the problem. The uncorrelated portion of any category we use not only does not help get us our desired overall total points/rating, but actually acts to deter us. Mathematically, it is said that the degree of uncorrelation is a measurement of the degree of uncertainty. It’s noise injected into our measurements, which is the last thing we want. Worse, outside of using weightings, there is little we can do to address the uncorrelated portion of the categories we use.

The honest answer is, unless you can identify individual categories with nearly 100% category-to-overall correlation, it is best not to use a category-based system at all. And good luck generating any category-based system that can boast perfect correlation!

And that’s before we even address how to add the categories together for an overall score. I haven’t the foggiest how best to do this.

I simply can’t see how the category method approach used by GD can possibly work without heavy administrative oversight. GW seems to take a more useful approach, asking panelists to grade categories as a means of stimulating architectural thought, but not using those category numbers in determining the overall score.

9. Should a private club decide to allow raters, what are prudent policies that it should employ in regard to green fees for raters, etc.?

Each club/course has to decide on the rater comping issue and do what they think best. Golf courses offer professional fees to many visitors and raters are probably a minor slice of this reduced/no fee pie. However, this issue has become more problematic now that there are ~3,000 raters traipsing around the world flashing their rater cards.

Some of you will argue with me but I believe (have zero proof!) that comping plays an exceedingly minor role in the outcome of the various rankings. My own experience is this: Yes, I’ve been comped – many times. Since I rate courses almost exclusively by myself, those comps have been limited to my greens fees, with only a few exceptions. I’ve never gotten private jet service, never accommodations, never golf shop merchandise (other than sometimes a yardage book). In the past, when I’ve had others with me, there were certainly times those folks were comped as well, although that is getting rarer.

I’ve posted something north of 1000 ratings for GW over 24 years, as well as other ratings for LINKS and GolfStyles. If I ever added up the personal expenses I have incurred rating those courses, I would likely need to send a note of apology to my heirs. I’m pretty confident, while I appreciate the gesture, that comping me has zero impact on my evaluation and I suspect that’s true with the vast majority of raters.

At my Florida club, I serve as a “club ambassador” for visiting raters. We have two old Ross courses that we like a lot but neither have any chance of making any lists. The board knows this but still offers a professional fee to the 20-30 visiting raters we get a year. I’m supposed to vet them prior to arrival (make sure they are really raters) and play with them if possible. Most raters are gracious, more interested in the courses and not concerned with any levied fees. Those that I have played with don’t seem to care, one way or another, whether they are comped or not.

10. You are extremely well-traveled, to say the least, having played 1600 courses in 35 countries. One of the benefits of raters (and others) seeking out new golf courses is uncovering hidden gems. Are there gems still to be found out there? Share three pleasant surprises you’ve discovered in your travels.

Undiscovered gems…. Once the world seemed to be filled with them but nowadays, with the many well-traveled golfers and discussion sites to post experiences, there are probably precious few remaining.

Over the early years I thought some of the following were, if not “hidden”, then certainly lesser known: [International] Banff (original routing. I first played there 40 years ago), Portsalon, West Sussex, Chantilly, Titirangi, Barwon Heads, Teeth of the Dog, Ardglass, and Enniscrone; [US] Victoria in Riverside is great and no one talks about it, Fountainhead in Hagerstown, MD is a virgin Ross that’s way under the radar. Palmetto was mostly unheard of until 25 or so years ago. Likewise, outside a group of summer campers, Lawsonia was once completely unknown. We stayed in a cabin at Green Lake 30-some years ago and couldn’t believe how good the pair at Lawsonia were.

Discussion groups and books like Doak’s Confidential Guide brought to light most of these places once thought of as hidden gems.

More recently I was blown away by Fazio’s GC of Tennessee. What a cool piece of property. It would be perfect except for the damned climb up to the third tee. What a ball buster. Reminds me of the first at Painswick.

Gamble Sands and Mammoth Dunes were delightful personal “finds” but they are hardly hidden. Ohoopee hasn’t yet been played by many so it is lesser known, or at least lesser seen, and waaaaaaaay good.

On my many trips to the UK, I’ve almost completed the UK top 100 list. I’ve played all the first and second echelon courses and am now mostly ferreting out the third echelon tracts that fewer folks see. My excellent resource is our own Sean Arble. Sean may be the king of those out-of-the-way UK courses, often scruffy and quirky, (not Sean — the courses!) but all with character. If I don’t know much about a UK layout, I wouldn’t think of booking a round there without checking first with Sean.

11. What’s your most unusual rating experience?

Unusual? How about this. Some years ago, I added a day to our annual outing at Sand Hills to go over and see the new Nicklaus Course at Dismal River. It was late in the season and there was literally no one there. In fact, I was the only player on the course and the only resident that night in the cabins. Chris Johnson (one of the five original partners) met me at the pro shop, introduced himself and sent me off on my way, promising to catch up with me somewhere during the round.

I played the first seven holes under cool and blustery conditions, very much enjoying some holes and others less so. Chris and another partner (forgot his name) joined me at the eighth tee (very short 2-attack option par 4). I took a driver and went for it. Chris and the other guy bailed to the less risky route. We looked in the scrub surrounding the green but couldn’t find my ball. I threw one down and hit it up and waited for the other two to hit their approaches. Putting out we found my original tee ball in the cup. An ace on a par 4.

That evening I had to buy everyone in the bar a drink (Chris, his partner and the bartender 😊). They bought me dinner. As we were eating, Chris texted another partner – Jack Nicklaus, and told him this Golfweek rater had just aced #8. JN told Chris to go into a back room and get a DR flag signed by Jack and give it to me. THAT was pretty cool!

That next morning Chris wanted to drive me around the southern portion of the property down closer to Dismal River. He was very high on doing a second course. He asked me who I would recommend he use as the architect. I said Doak. Chris had barely heard of Tom Doak. I told him I would contact Tom (which I did that evening) and tell him of the potential Dismal project. Tom answered right away telling me that there was a lengthy list (including Youngscap, Keiser, Crenshaw and Coore) who would need to be consulted before he could entertain building a course 8 miles from Sand Hills. Anyway, that was the end of my involvement and you all know what ultimately turned out, but that was pretty unique rating experience to say the least.

12. Most uncomfortable experience?

Easy – whenever I’m paired with a club member, especially if it’s a board member. They tend to put way too much stock in a single opinion. Your comments have to be positive no matter what you see. I’d much prefer to do this rating business by myself.

13. Most rewarding?

As for most rewarding, I guess rating at least one course in each state. Finishing at least one of the top 100 lists would be cool, too, but I’m not sure I’ll ever make it. I’m close on most lists (80-90% complete) but at 68 years old I may be running out of time.

14. What recommendations and insight would you give a perspective rater on how to become a rater?

GD and GW are recruiting on pretty much a permanent basis. GW considers new applicants twice a year (June and December). Digest has a website where you may submit an application. The process of applying to these and other panels outside the UK is outlined in the last chapter of the book. To get onto the GOLF Magazine panel is the hardest, and from a recent conversation with you, I know that you are thrilled with the current make-up of GOLF Magazine’s panel and that any additional panelists will be carefully vetted and added at a measured rate.

15. Do you need to be a strong player to be a rater?

No. In fact, most of us (raters included) aren’t very good at golf and some of the most brilliant minds on golf course architecture are mediocre players. Innovative landforms designed by an architect to impact a player’s attack are much easier to recognize and functionally understand than they are to properly execute. “I see that kick point or punchbowl — if only I could hit the shot to take advantage of it!”

As you have correctly pointed out to me, there probably should be a handicap limit for a player trying to both play and rate. The better player who plays poorly is still likely to sample many of the intended architectural highpoints of the design. The architecturally adroit higher handicapper, also playing poorly, may be so consumed with advancing the ball out of his shadow that he may well miss compelling course features and get less a sense of a course’s character. It may be better that he survey the course without playing. The USGA course/slope volunteers do just this – rate the course first and then play it.

Here is an aside about the enjoyment-to-playing ability relationship.

In my experience, there is zero correlation between how well you play and how much you enjoy playing golf. Some of the worst hackers play golf with permanent smiles pasted across their faces, while a plus two may go around a course muttering and snarling the whole way.

Most great courses are too hard for me, but I seem to like them just the same. I love playing Kiawah, LACC, Oakmont, and Whistling Straits, even though scoring well is beyond my ability. My own home course of 34 years – TPC Potomac (Avenel) is impossible; the precision required for your approaches may be the most difficult of the 1600 courses I’ve seen. There was a reason Gary McCord called it “The Beast of the Beltway” and Justin Thomas said, “You can host the US Open here tomorrow without changing a thing.” But oddly, most members, including me, love the place. I guess we are golfing masochists.

There is a great degree of exhilaration and satisfaction in occasionally executing a challenging shot successfully. Unfortunately, a higher handicap has less opportunities to do this as does a lower handicap. But a little goes a long way. So, an architect who can design in features that give players of all range a chance for his opponents to say, “Great shot!”, then most players can probably live with difficult courses.

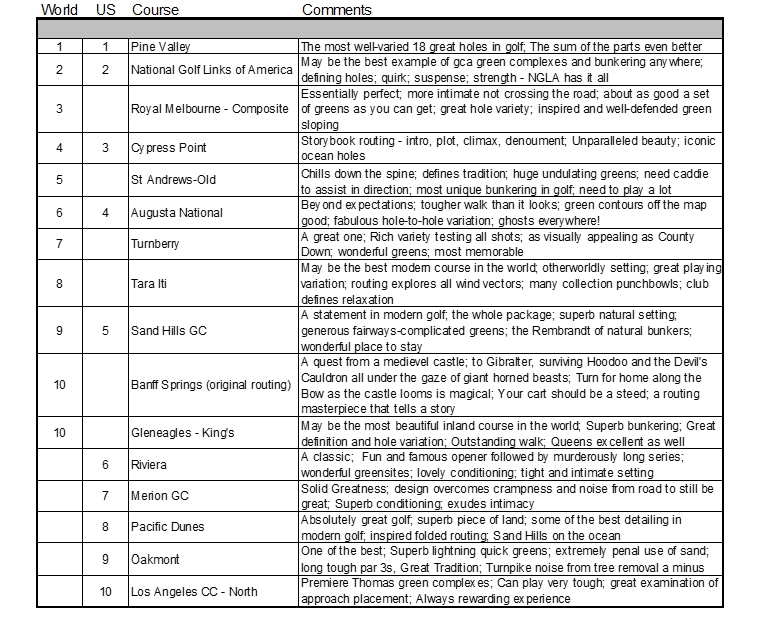

16. Okay, let’s see what you are made of! What are your top 10 courses and why?

I snuck in two #10s on the world list 😊. The Dornochs, Sunningdales, Lahinch, Down, Seminole, Bethpage, Chicago, Fishers, Shoreacres, Valley Club, Shinney, Cabot, Winged Foot, Somerset and a bunch of others wouldn’t be far behind the list below.

17. That’s really neat to see the Kings Course at Gleneagles featured so highly. It isn’t a monster but it is challenging and as you note, it may be the most beautiful inland course in the world. What are some examples of the design components that James Braid employed that strike that elusive balance between difficulty and fun?

The King’s is a short course featuring wide fairways for your tee-shots, and ever-varied, compelling targets for your approaches. His Majesty’s greensites are magical; many perched on small mesas or partial ledges with fascinating shoulders to complicate recoveries. Symmetric but expanding conical flat-bottomed bunkers, which act bigger than they are, forever come into play. The inventor of the dogleg, at Kings, there is at least some bends and angles to each of the Braid’s holes.

The King’s strives to examine not every club in your bag, but every shot in your arsenal.

Visually, on the playing field, Braid is able to emote anticipation, awe, triumph, foreboding, and exhilaration – all through design. And if you look up, in every direction you are rewarded with pleasing views of soft rolling contours melting into the playing field along with distant vistas of the surrounding moors and the Ochil Hills of Perth. It’s not the dramatic beauty of an Old Head, but a softer ordered beauty of pure nature that grabs you.

Others will describe it differently and likely better, but there are few courses in the world that can brag the right amount of challenge, fun off the map and unparalleled pastoral beauty.

18.What is a red flag for you that a course may be ‘overrated’?

I guess the number one red flag for me is an over-reliance on tournament tradition. Great courses may also have great tradition. Some are great with zero tradition. If I sense that a course is full of itself because of its tradition of hosting prominent tournaments, but the course is not architecturally deep, it can’t help but effect my rating.

Big and brawny can also be a red flag that a course is trying to mask a lack of interesting design features with muscle. The same is true with conditioning. I love a well-conditioned course, but some clubs try to wow a player, boasting Augusta-like conditioning, all in an effort to distract from the fact that the design is more mundane.

Boldness, imagination, innovativeness, experimentation and the ability to integrate into the surroundings are all green flag items to me – all attributes likely found at under-rated courses.

My sense is that there are a lot more quietly under-rated than over-rated layouts out there.

19. Is beauty the biggest component that can blind a first time visitor to the shortcomings of a design?

Geez, how can’t you be blinded the first time you play the likes of Kidnappers, Kauri Cliffs, Old Head, Bandon, and Pinnacle Point. The dramatic beauty of these seaside places, amplified by the vertical component, defines the “wow” factor and can’t help but obscure (at least initially) the golf course. But how do we get a handle around measuring this? Not sure I can answer well but here are a few thoughts.

Beauty is a broad category and may be measured in many ways by different but equally capable evaluators. Breathtaking backdrops are almost universally applauded, but beauty may be found in things other than scenery. A golfing botanist, gardener, or forester may find great beauty in the pleasing arrangements of trees, floral and other things growing. Those with an agronomy background may find beauty in an architect’s and builder’s ability to move water (drainage). An architect playing a fellow architect’s course may find beauty in novel and innovative landforms, movement and setting.

If you find yourself continually distracted away from the golf course itself, think about why. Ask yourself, “If the scenic distractions were not there, how compelling is this layout?” If your answer is that you would prefer to be hiking or picnicking, then that should tell you something. On the other hand if you find yourself surprised after a round to hear a fellow player remark how beautiful the course was and you hadn’t noticed, that may also tell you something – like you may need to, when playing a round, raise your head once in a while.

If you can solve this great puzzle it may be illumining as to how important setting is to you – move Sand Hills to Fanshell Beach and Cypress Point Club to Mullen, Neb. and tell me how much either goes up or down in rankings. My sense is that little changes, but others may well differ.

The best answer may be found in subsequent plays. If the character of the golf course draws you in as you become more use to the setting, that should say something about the architectural quality. If it doesn’t then pack a picnic basket and enjoy the views.

The point is natural beauty can be a very important component to a golf course, but it can never be the reason you are there. Probably best to view beauty for beauty’s sake, as the icing on the cake, but never as a replacement for good architecture.

l to r, Rick Holland, Jon Cummings, and Mike Nuzzo in the Canadian Rockies for a GCA gathering 2004.

20. Suppose you are promoted to czar of all raters. How would you form and run a panel to generate the best lists possible? As part of that answer, please define ‘best’!

Fun! I’m assuming I have a complete blank slate and resources aren’t an issue.

OK, first thing is recruitment. I would select raters who are widely traveled, have the time (retirees are usually a big plus), are financially secure (forget comping – well traveled golfers will spend a ton of their own money), and who have a demonstrated strong curiosity about why a golf course does or does not work. I would recruit 1000 such raters – geographically balanced as much as possible. I wouldn’t care about handicaps as long as a rater showed some architectural depth of knowledge.

Second is method. I would use a 20-scale scoring, requiring raters to submit a 1-10 course ratings in half steps (1, 1.5, 2. 2.5….9.5, 10). The Doak non-linear scale would be used or closely approximated. I would use the GW categories and ask raters to rate each, and like GW, I would not use the category data in determining rankings but would use them if I needed to explore more an unusual rating. Each rater would be required to submit ratings for the individual courses they saw, AND to keep a running spreadsheet of the courses they played, ranking them from best to worst without using any numbers.

Finally, processing data to arrive at the lists. I would generate three lists and compare the three to come up with final rankings:

(1) a ranked list generated from the averaged numeric ratings (where bias, outliers, and other data collection errors are addressed). I would list numeric ties and make no effort to break ties using resolutions beyond those measured by the raters. Absolutely no averaging to the hundredths place;

(2) a merged single ranked list laterally combined from the ranked lists of the 1000 raters (the methods are outlined in the book); and

(3) a similar merged single ranked list laterally combined from the ranked lists of the 100 best of the 1000 raters.

Posting the lists. I would publish all three lists separately. Finally, I would generate a 4th list which would be a combination of the published three. Each of the three single overall lists would be merged laterally using the same process as was done with lists 2 and 3 to form this last list. Call it a composite methods list.

I would publish all three core and the final combined lists in an effort to give the reader the sense at how variable (based on method) these lists can be. That may give some pause when they find themselves arguing over some exact ranking of some course.

There may be one or two of you with other ideas on how to do this, but since I’m czar, I get to send you to Siberia if you disagree with me 😊.

————-

As I said before, The Rating Game was an enormously rewarding project. I’m somewhat bummed it’s over. I hope the reader gets even a small portion

of the satisfaction in reading this book as I got in writing it. Thanks Ran and all of you, and Happy Rating.

JC