Feature Interview with John Moreton

August, 2014

John Moreton began his career as a golf historian in 1991 upon gaining early retirement from the teaching profession. His first book was “The Golf Courses of James Braid”, published by Grant Books in 1996. As a result he gained commissions to write club histories and the centenary histories of the Worcestershire and Warwickshire Golf Unions He also served as the Junior Organiser for the Worcestershire Union of Golf Clubs, becoming the union’s President in 2007. He has lectured to the British Institute of Golf Architects on James Braid and given a similar lecture to trainee greens staff at the Geneagles Hotel. He was also a visiting lecturer on the social history of golf for the Birmingham University course, B.A in Golf management Studies.

His latest book James Braid and his Four Hundred Golf Courses is available from Grant Books, The Coach House, New Road, Cutnall Green, Droitwich Spa, Worcestershire WR9 0PQ, Great Britain £25.00 + £6.00 p&p overseas. email: golf@grantbooks.co.uk

1. What prompted you to update your original 1996 book The Golf Courses of James Braid?

After the first book was published Iain Cumming contacted me, saying he had played several courses in the book but also others attributed to Braid. Would I be interested in doing an update? I agreed as Iain then lived in London with access to the British Newspaper Library at Colindale , North London. There he was able to consult back numbers of Golf, Golf Illustrated and other periodicals. I had already been there to look at two Irish magazines which furnished much of the information for the first book. Iain joined the James Braid Golfing Society and we travelled to Brora, stopping on the way to examine other courses. I had already been there to discuss the foundation of the society and played both Brora and Golspie on the same day in March and returned to Birmingham the next day with a sun tan!

Iain then made contact with Marjorie Mackie, Braid’s granddaughter who ran a bed and breakfast in Cardross. We stayed there on two occasions and played the Braid course there and visited others in the area. We sometimes visited five courses in a day, not to play, alas, but to dig out as much information as we could. We even had a day at Gleneagles with Marjorie and her daughter Fiona at the invitation of Jimmie Kidd, the Estates and Course Manager, who had been very helpful with the first book.

Our research spread over a number of years as I have other writing commissions and Iain and his partner had moved to a village in East Sussex.

We were genuinely surprised at the number of courses he visited according to Golf Illustrated. We also had to check some of the spelling of course names as in the early days correspondents sent in hand-written reports and the typesetters sometimes misread them!

2. Prior to your efforts, the number of courses I had seen associated with Braid ranged between 100 and 200. Your revised tally of around 400 is a staggering amount! Do you have a general breakdown of what work occurred? How many were new 18 hole courses? How many were remodels?

See introduction for breakdown of work. Much of the work involved remodelling and extending nine holes to eighteen, in which case the new holes would absorb the original holes in a playable layout. When asked for advice on bunkering, for example, he would offer other suggestions for improvements.

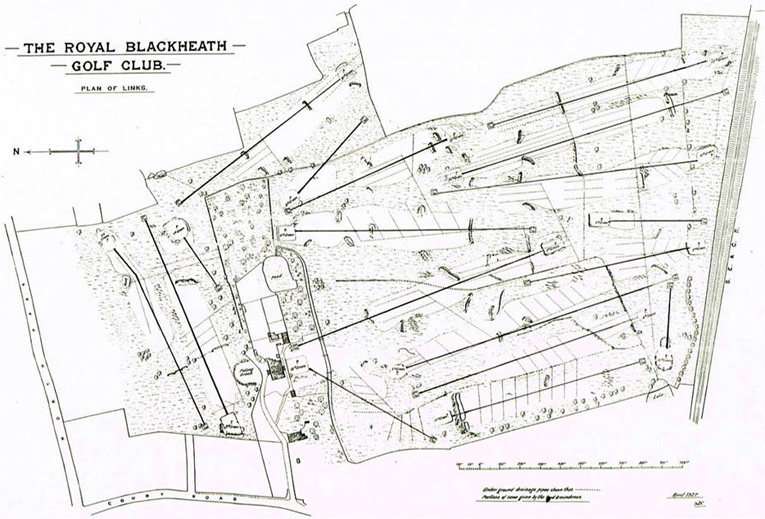

Braid made alterations to over 200 courses in his career. Above is his plan for Royal Blackheath, where alterations including a new bunkering scheme were carried out in 1926.

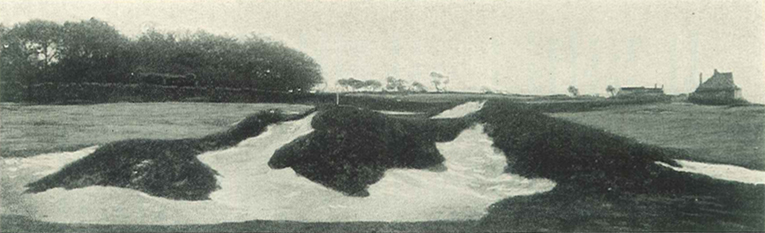

Braid’s bunkering style evolved with time and by 1920s, he and John Stutt were building some of the best in the United Kingdom. Pictured above is one from their work at Royal Blackheath.

3. Just to get around to 400 different courses is an accomplishment, let alone doing some of it before the automobile had achieved popular use. Was most of his travel by train?

Most of his travels were by train. The rail network extended all over the British mainland and he suffered from travel sickness in motor cars and ships (see Hamilton Stutt’s foreword). He would travel to the venue, walk the course, sometimes with stakes to mark tee and green sites and catch the night train home to Walton Heath. On the journey he would draw his plan from memory. On reaching the office he then wrote a detailed schedule of each hole, with specific instructions about distance from the tee for bunkers, greenside bunkering, which trees to fell and which to keep. He tried to save a many as possible. His constructors, to begin with local crews, then Fred Hawtree senior and finally John Stutt. Stutt was able to interpret Braid’s plans and implement them to the letter. Apparently Braid also enjoyed reading cowboy novels while on the train or if travelling with fellow golfers he enjoyed a game of brag.

4. When you started researching Braid 20 years ago, did you have certain preconceptions about Braid as an architect? If so, which were proved or dispelled during your years of research?

I became conscious of his design work when playing Mullingar in the Irish Midlands, one of his masterpieces. It was a challenge for the crack golfer but eminently playable for the handicap golfer. This experience was repeated on visits to other courses and this is what inspired me to research his work. I had read Darwin’s biography by then and soon realised there were numerous inaccuracies – Darwin played up the motion sickness and barely mentioned the Irish visits which involved some very rough crossings.

This aerial of Royal Blackheath after Braid’s work highlights how the course was fun for all players with its width and challenging greens.

5. Did you find much in writing from Braid himself in terms of his views on golf course architecture? Any favorite quotes? Your book is certainly littered with them.

Braid wrote three books, two coaching ones, one of which was for lady golfers and Advanced Golf, which ran to many editions. This is where the quotations about course design come from, with diagrams and photographs.

6. What was the typical commission that Braid received for designing and building a course?

Braid tailored his charges according to the requirements and financial circumstances of the club. A normal fee would be ten guineas (£10.10s.0d) plus travel expenses. One club we visited had lost the minute book for the year he visited but I spotted the ledger for the relevant year and we discovered two payments, one for design and one for travel. Braid noted these down in his ledgers – see illustrations pp 235 & 242 where different charges are recorded.

7. When a club hired Braid, what did it get exactly? Did he route the holes and then left it to others to build the course?

Braid routed the holes and in the early days supervised some of the construction if local crews were used. Later he was able trust Hawtree and Stutt to implement his plans (see above). It should be remembered that until the latter half of his design work earth moving was minimal as it had to be done by hand. Scrapers were dragged by horses or stationary steam engines. Natural features were retained as much as possible.

8. In the process of compiling all the information, what surprises, if any, popped up along the way as you gathered information?

I suppose the biggest surprise was the fact that he visited just about every corner of the British Isles, although there are not many Braid courses in the English midlands – the 60 mile radius around Nottingham was Tom Williamson’s fiefdom. Tom was a good friend of Braid and created some fine courses.

9. What work did he do at Carnoustie?

Braid visited Carnoustie in 1926 to prepare it for the Open Championship of 1931. The present course follows his plan with few, if any, significant changes. He made good use of the natural terrain, notably the Barry Burn. Some of his ideas were unpopular with his fellow professionals – the hidden first green, the central bunker on the second fairway, for example. (Please see book for further examples).

10. How much of Pennard as it exists today is Braid? Did he do the original routing or just remodel holes there?

Six of Braid’s original holes remain at Pennard, the rest have been either lengthened or remodelled. It is one of the most spectacular courses in the country and very highly regarded. American writer Jim Finnegan rates it as the best in Wales.

Sean Arble’s photograph of the seventh hole at Pennard showcases the splendors of this Welsh course.

11. What are three of his wildest putting surfaces?

The ninth hole at North Shore , Skegness, comes to mind, although I only needed one snaky, double breaking putt for a birdie. The par 3 fourth at North Worcestershire has a tricky sloping green – fatal to be above the hole. Sadly this course may soon be sold to a building company. Some of the Brora greens are among the most difficult to read, especially the eighth.

12. What is a favorite par 3, par 4 and par 5 that he designed?

I’d cite the par 3s at Brora as favourites – each in a different compass direction as per Braid’s philosophy. There are some strong par 4s at North Hants, one of which has been changed but the last two take some beating. The par 5 8th at Brora is a classic, with the green on top of the dunes.

13. One of the handful of greatest players in the world for several decades, how did his designs make allowances for the lesser player? Did he ever set out to build a singularly hard course ( a ‘championship course’ in today’s parlance), one that was intentionally geared toward testing a man of his supreme abilities?

Until the proposal to create a course at Gleneagles was formed, most golf courses were at private clubs, where not many members were low handicappers. Braid was conscious of this. For example he rarely sited cross bunkers in fairways. When playing an exhibition match, he would be playing the same course as the club’s members, so would have recognised where the lesser player may have problems and offered alternative routes to the tougher holes.

The idea of a “championship course” is a relatively new one – remember, the Old Course belongs to the people of St Andrews as does Carnoustie. We now refer to them as championship courses but how often do they actually stage “championships”? Course designed as “championship courses” these do no favours for the average golfer; some might even be described as “vanity projects”.

Braid’s work was the equal of the so-called “golden age” designers. He was even called in to remodel work by Colt and Mackenzie, who tended to go for more prestigious clients. Braid’s aim was to provide enjoyable golf courses for whoever chose to commission him. His reputation earned him such commissions as Gleneagles.

14. Given his tenure at Walton Heath, does it surprise you that he never touched either course there?

The Walton Heath courses were both designed by Herbert Fowler, who was in effect Braid’s boss at the club. It would have been more than his job’s worth to meddle with Fowler’s work! It is clear that they shared their ideas though – the bunker in the Braid idiom on the frontispiece of the book was actually Fowler’s work!

15. Popular consensus on GolfClubAtlas.com suggests that St. Enodoc, Pennaporth, Brora, Gleneagles Kings, the extensive remodel of Fraserburgh are his best, most enduring designs. Would you agree with that assessment?

I would agree with that assessment, having played the Kings, Perranporth and St Enodoc, but not Fraserburgh, I’m afraid. I would add East Renfrewshire, south of Glasgow, a delightful course amongst the pine and birch; Ipswich – Purdis Heath, one of his masterpieces. Two other masterpieces no longer exist, The Naze in Suffolk and Dunfermline’s third course at Torrie House, on Lord Wemyss’s land, now grazed. Iain and I walked it with the golf club’s secretary. Andrew Wemyss wanted to restore it but unfortunately has been unable to do so. Tenby in Wales also ranks very high in my estimation. Admittedly, I did play there the day G.B. & Europe won the Ryder Cup in 2002! It is a classic links course.

Braid worked on every type landscape imaginable throughout a career that brought golf to many people across the United Kingdom and Ireland. One of his best sites was the crumpled linksland at Fraserburgh in northeast Scotland.

16. He won five Opens from 1901 to 1910. Old Tom Morris passed away in 1908. After his 1910 victory, could Braid lay claim to being the most famous golf figure in the United Kingdom?

Braid shared his fame with J.H.Taylor and Harry Vardon – The Great Triumvirate. The last two also designed courses, Taylor specialising with Fred hawtree senior in municipal layouts, while Vardon’s health restricted his activities. Sixteen Open Championships among them for all three to be recognised as the U.K.‘s most famous golfers

17. Am I missing something or did Braid never come to America? Wonder why?

You have missed something! Braid could never have undertaken the long ocean crossing to the U.S.A. because of his motion sickness. He was extremely brave to go to Ireland and the Isle of Man on a number of occasions and also the continent, although Darwin seems to have ignored this.

18. Closing thoughts?

I should like to add that in the book many of the illustrations are from old postcards with the intention to show what the course may have been like when he was there.

It is unfortunate that modern equipment is making some century old courses obsolete as very few have the room to expand. The best way to play them now is with hickory clubs to experience the way the course played when first laid out.

You are preaching to the choir on that point! Thank you for your time.

The End