Feature Interview with Ed Brockner

August, 2021

1. Tell us about the origins of Hendricks Field Golf Course. Who commissioned it? Who built it? When did it open? Etc.

Essex County, NJ was the first County in the United States to create its own parks system in 1895, beginning with Branch Brook Park in the North Ward, or Forest Hill section, of Newark. Frederick Law Olmsted visited the area some years earlier and deemed it a suitable location for Newark’s answer to Central Park, with the Olmsted Brothers firm completing work at Branch Brook along with a number of other parks in the County. To the north of Branch Brook was Forest Hill Field Club’s golf course built on property leased from the Hendricks family, who had owned the land since 1794, and established their homestead and Soho Copper Works on an adjacent parcel in 1813.

The Olmsted firm designed Weequahic Park at the southern end of Newark soon after Branch Brook. The centerpiece of this three hundred plus acre park was its large lake, and in 1914, a nine-hole golf course opened as the first public layout in the state (with nine more added in the late 1960’s). The original nine was designed by George Low, the golf professional at nearby Baltusrol Golf Club, and proved exceedingly popular as noted in an article from 1926:

“Following the close of the World War, the Weequahic links became the recreation ground of hundreds of youths whom war participation had made accustomed to out-of-door life. Golf fans doubling, trebling almost overnight, the links at once became popular and crowded. In the past two years, the links have been too crowded most of the time, 60,000 and 80,000 games roughly, having been played there in the two successive seasons. More than 80,000 games probably will crowd the records at Weequahic with the season just begun.”

With the growing population in the area, Essex County began planning to expand Branch Brook Park to become more than three hundred fifty acres in total, including acquisition of property owned by Harmon W. Hendricks who represented the last living member of the family. To accommodate the park plans in 1924, Hendricks sold much the property at a discount to the County, and donated an additional twenty acres that comprised the family homestead to Essex Parks that was valued at $100,000.

This portion of property was intended for the construction of a parkway at the terminus of the park’s proposed Northern Extension, but members of the county’s Municipal Golf Club successfully lobbied to instead use the land to construct an 18-hole golf course as justified by the popularity of Weequahic. Through a public referendum the following year, $500,000 was authorized to purchase additional property totaling about 130 acres, and fund construction of the course contiguous with Branch Brook Park that was named in honor of Mr. Hendricks for his generous donation.

Edward Jackson, commissioner of the Essex County Park board, was a principal driver in the development of the project and the Commission hired Seth Raynor to design the new course that also included part of the Forest Hill layout (the club later bought land a mile away hiring A.W. Tillinghast to build their new course). It is unclear to what extent Raynor played in the planning, but it appears from the following quote that credit for the design belongs to Charles Banks due to Raynor’s untimely passing:

“Seth J. Raynor, a golf architect, was employed by the Park Commission to lay out a course. Mr. Raynor died in January before he could get the work more than just started. His associate in business, Charles M. Banks, subsequently was engaged for the task.”

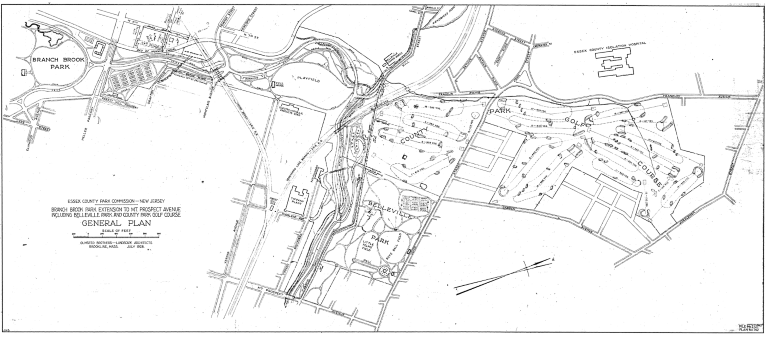

The course opened in 1929 and included many of the classic holes from the Macdonald/Raynor/Banks repertoire including the Redan, Double Plateau and Eden. While an original plan showed more than 100 bunkers to be constructed, as-built drawings indicate that less than 20 were ultimately built. The slope and size of the greens and bunkers was also at a much gentler and smaller scale compared to their other courses; owing to its use as a municipal layout. Below is a plan from Olmsted Brothers that lays out the Northern Extension and “County Park Golf Course.”

The course was very well received with Weequahic also remaining very popular, and hosted the inaugural Metropolitan Golf Association Public Links championship in 1936 (followed by the newly opened Bethpage Black the following year).

3. How did Hendricks fare during the last century?

It appears that Hendricks was maintained in decent condition as it hosted numerous state and regional tournaments including the 1970 New Jersey PGA Championship that also marked the 75th anniversary of the Essex Parks Commission. The irony is that the lack of large maintenance budgets or over-zealous greens committees resulted in green complexes and course features being little changed (other than some lost bunkers) over the first eighty years of its existence. The main issues were shrinking of green pads and trees growing over time, but it was more of a slow deterioration and lack of investment in infrastructure that led to a situation that had become dire before the County began making improvements in 2006-7.

4. What was the nadir for the course?

The nadir of the course was in the mid 1990’s when the County brought in the USGA to provide a consultation report authored by longtime Green Section staffer David Oatis. He offered an unvarnished assessment of the County’s three courses at Weequahic, Hendricks and Francis Byrne – which was the original West Course of Essex County Country Club also designed by Charles Banks. The report laid out a blueprint for a plan moving forward to improve the courses, but virtually none of the recommendations were put in place due to lack of funding and staffing at that time, along with little political will to invest over the next ten years.

This was also around the time that the USGA awarded the U.S. Open to Bethpage Black that represented an important moment in the recognition of muni golf. Growing up playing at munis on Long Island and at Bethpage in particular, most were in awful condition and had poor management. The investment in Bethpage showed municipal owners what was possible, and started the trend that has continually gained momentum in the twenty-five years since. And just Great Depression gave the impetus for the construction of Bethpage and hundreds of other munis around the country, our generation’s crisis with COVID has highlighted the need for outdoor recreation with public golf experiencing a boom in participation and hopefully further municipal investment.

5. When did you become involved and what is your role today?

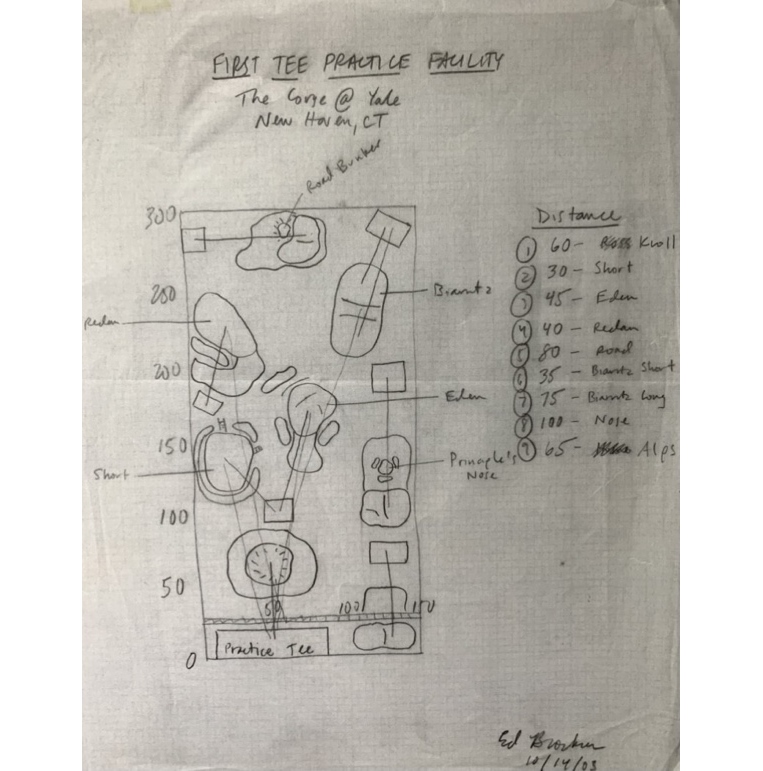

My interest in First Tee and building accessible golf facilities started in 2003 when I returned to Yale two years after graduation as a volunteer assistant. Working under for former coach David Paterson who has been a close friend and mentor, part of my motivation in taking this role was to help bring a youth program to Yale to serve the New Haven community. With a new range planned at the time, along with a need for a long-term strategy to improve maintenance practices and properly restore the course, it seemed there was an opportunity to build a facility on the existing range for dual use of First Tee and the university golf teams. Bethpage provided a model in terms of pricing structure with reduced fees for university affiliates and market rate for others, with the added benefit of serving the New Haven community and leveraging Yale’s educational resources. Although First Tee CT eventually started a small program at Yale, the full plan never came to fruition (my decidedly amateur sketch from the time is below), but it planted the seed in my mind that the classical principals of Macdonald could be adapted to youth and public golf facilities, in a manner similar to how his architecture borrowed from the British links through his designs in America.

The 2003 Macdonald Cup at Yale featured Gil Hanse as guest speaker at the dinner, and a conversation with him there led to him letting me work on his crew at Boston Golf Club and then Country Club of Rochester; seeing both new course construction and classical restoration at its best. I am so thankful to Gil for being so generous with his time, and in giving me the opportunity to get this hands-on experience. His example demonstrated the critical need to spend a lot of time on site to make sure the small details get the proper attention as the work is ongoing.

This all led to me being hired to work for First Tee of Metropolitan New York as construction manager for the redesign of Mosholu Golf Course that was their only site in the Metropolitan area. Mosholu is situated in Van Cortlandt Park that was also the site of the first public golf course in the States built in 1895, with Mosholu built in 1914; coincidentally the same years that Essex County, NJ established their Parks Commission and its Weequahic course respectively. Mosholu’s course would later become just nine holes to make room for a driving range, create more park space and reduce safety issues with golf balls going into heavily populated buildings and roads. When the First Tee Metropolitan New York Chapter was established, it provided a perfect location with the large practice range, proximity to the subway/major highways and potential for improvement. The Metropolitan Golf Association, Met Section PGA and Rudin family were the three founding partners in this endeavor in 2001.

Several years into First Tee’s twenty-year concession in 2004, the acreage of the golf course was further reduced with NYC needing to use a portion of the property for its new Croton Water Filtration Plant. The NYC Department of Environmental Protection provided funding to redesign the course using Stephen Kay with a new driving range and clubhouse built within the smaller footprint. At 2,300 yards from the tips, we focused on making a course that while not overly difficult, still offered some fun challenge and compelling design features. A guiding principle of the work was that for those just learning the game, it was even more important to create interesting strategies and incorporate classical principles to make it a course people wanted to come back to.

Most of the holes were completely original in nature, but the Redan-inspired par three third, and “Bronx Biarritz” on the ninth were borrowed from the Macdonald design school. Roughly fifty yards long with a prominent swale in the middle that plays slightly uphill, it provided an unexpected and enjoyable conclusion to one’s round at Mosholu for muni golfers. In working with Stephen, it seemed fitting that the flagship home of the First Tee created to make the game more inclusive in the region also included design features found on many of the best, but strictly private courses of Macdonald, Raynor and Banks in the Met.

In seeking additional communities where we could serve youth with a focus on those from diverse populations, along with existing public facilities that could benefit from investment and a facelift, Newark and Essex County, NJ’s Weequahic Golf Course provided perfect next project. The course had been badly neglected and there were no practice facilities to teach First Tee, but Essex County was in the process of a major parks overhaul partnering with non-profits that provided youth and community programming under a new administration. Thanks to Ralph Ciallella from Essex County, we identified a blighted area between the course and railroad tracks that was about five acres filled with debris that First Tee transformed into a dedicated youth practice area.

|

With the help of a USGA grant that gave the project a higher profile and legitimacy, we were then able to reach out to other funders to get seed money from the NJ State Golf Association, NJ Section PGA and the Ryan family. Stephen Kay donated his design services and we built three artificial greens loosely based on the Short, Eden and Redan that doubled as a short range. It offered a great place to teach the kids and for them to call their own, along with free access to the course at off-peak times. This success created a spark for the improvement of the golf facilities in Essex County overall.

Following the project in Newark in 2006, the County hired me to work as golf consultant for their three golf courses to create long-range master plans and provide management advisement that resulted in increased revenue and usage. The $7 million bond the County took out for improvements in 2007 to address infrastructure needs at Weequahic, Hendricks and Francis Byrne was paid off in less than ten years, through increased play while continuing to maintain green fees that are extremely affordable. The biggest increase was at Weequahic where there were only about 11,000 rounds played in 2005 and by 2019, this number had nearly tripled to over 30,000.

On the community and youth programming side, First Tee has invested more than $5 million over this time (with the Ryan, Wilf and Fireman families providing a significant portion of the funding) through high quality instruction for students and education initiatives including college scholarships. Katie Rudolph, an extraordinarily gifted PGA and LPGA professional, led programs there for the ten years leading up the restoration, along with major improvements made at Weequahic to the clubhouse through state and county grants in 2012 and 2017. In my most recent role as Executive Director of First Tee from 2015-2021 (after ten years as Director of Development) along with our staff and donors, our organization built a great deal of trust in the Essex County and Newark community with a track record of service through our programs and successful facility improvements.

All of this set the stage for us to work with the county and state to complete a plan for Hendricks Field in seeking to expand our municipal model of partnership with First Tee: investment of public funds to restore and enhance open space combining the spirit of Olmsted and design tradition of Macdonald, with First Tee and its philanthropic partners committing to fund programs over the long term to support community-based education initiatives.

6. How did you go about galvanizing support for a restoration?

With the demand for programs and difficulty for students from Newark’s North Ward and surrounding towns to access Weequahic, First Tee and Essex County sought to create a new Campus site at Hendricks Field. However, there was very little available land to build a similar facility to Weequahic, and a desire to build a larger “Learning Links” where youth golfers could have a true a golf course experience. While the increase in play due to improved conditions at the County courses generated additional revenue, it also had the unintended consequence of providing less tee times for the kids to use with increased demand. By building an area with several practice holes, it would alleviate these issues for beginning students’ access, offer an outstanding practice area, and allow youth to then graduate to the main course when ready. To make this possible, it would necessitate an expansion of the golf course into an underutilized section of Branch Brook Park and provide the justification for investment in the restoration, renovation and redesign of the course as a whole.

In addition to the three short holes, First Tee and the Ryan family funded the design of the Learning Center that will serve as a community anchor with year-round education programs providing the project with a purpose beyond golf. There are many youth in financial need in the surrounding area who do not have access to programs like First Tee, and the tutoring, STEM and college program programs the Met NY chapter teaches. There will be numerous scholarship and youth employment opportunities, including the use of this facility as a focal point of efforts in New Jersey to grow the number of Evans Scholars in my new role.

There were many individuals who galvanized support of the restoration, and the youth education programs that the revamped and expanded facilities could provide. Those who deserve the most credit for gaining funding and support are Essex County Executive Joe DiVincenzo and NJ State Senator Teresa Ruiz. The County Executive, an avid golfer himself, has been a tireless supporter and advocate for parks and youth programs since we established First Tee. Senator Ruiz, whose district includes Hendricks Field and helped secure state funding for the project, was an important voice within the county and state. As the Senate’s educational chair, she championed the project’s benefits providing programs and facilities for minority youth in financial need, who would not otherwise gain exposure to golf as they do to other sports.

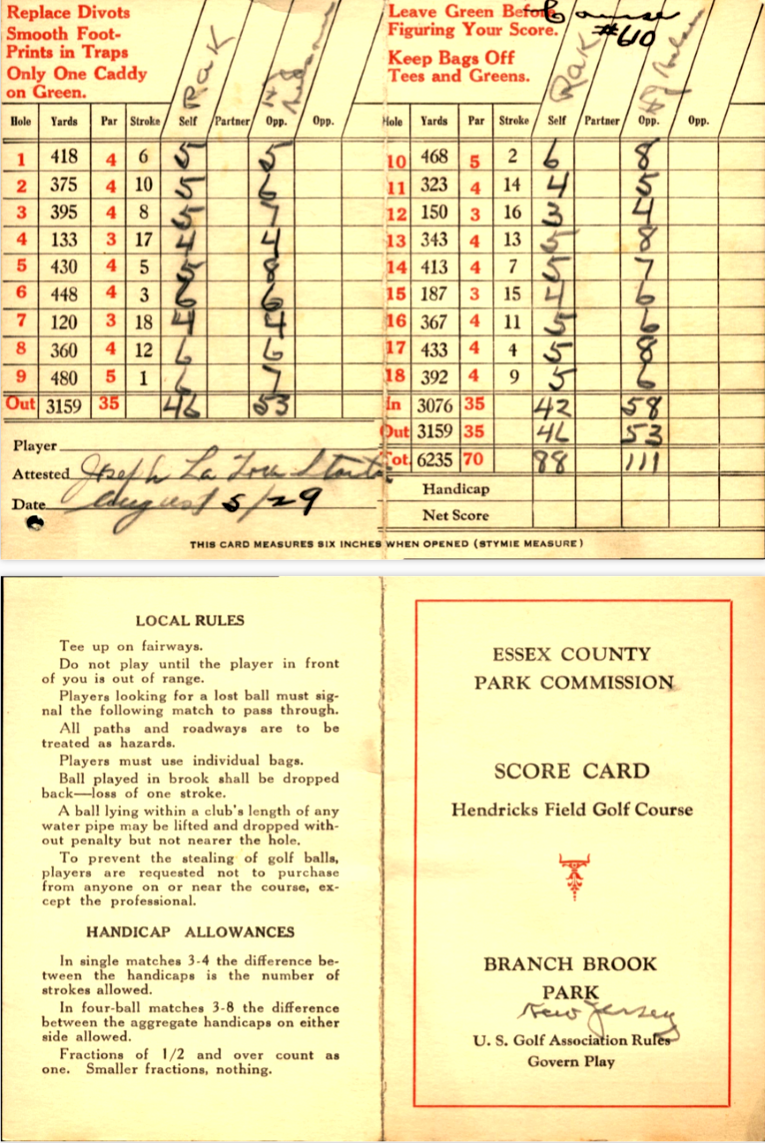

As we were gaining momentum on the funding side of the project, concerns raised by the NJ Historic Preservation Office nearly stopped the entire efforts in its tracks in late summer 2020. The portion of Branch Brook Park to be used for golf course expansion was determined to be part of a historically designed landmark area that could potentially prevent its use for golf. However, we presented historical maps showing that the original clubhouse and previous Forest Hill Field Club course played through the area in question, along with a scorecard uncovered in the USGA archives from 1929 proving that the course started and ended at this point in its early years as further evidence.

|

A scorecard from the opening year of the course in 1929 shows how the course started and ended at the part of the park In the process, we were actually restoring the original use of the land as historic golf space that predated the park’s Northern Extension. In addition, at which time of expansion, Branch Brook Park and the golf course as shown on both the Olmsted plan and scorecard were not separate, but rather integrated together in the form of active and passive recreation. The Ryan family was also integral in the process as they have been since the founding for First Tee Essex County in 2005. As major benefactors of the park, the Ryans provided us with an introduction to Barbara Bell Coleman who is chair of the Branch Brook Park Alliance. Her advocacy of our plan to incorporate a portion of the park aligned with the goals of the Alliance in better serving the community, and gave us much needed support. In her letter to the historic preservation office, she wrote that she believed the First Tee program, combined with course improvements, would “become a national model” in serving the immediate surrounding neighborhood:

“As residents engage with this program, all youth will have the opportunity to experience what Frederick Law Olmsted believed to be ‘chance meetings’ of people of all walks of life, from all backgrounds, race, creed color and socio-economic backgrounds to interact and be in relation with one another.”

The planning and approval process for the project also coincided with the worst phase of the COVID-19 pandemic that struck Newark particularly hard, and heightened the need for equal access to open space for urban residents; making the case even more compelling for sustainable municipal golf combined with a youth program that promotes environmental justice. This was also in line with the Olmsted philosophy that drove the creation of the Essex Park system in the first place, and the physical and mental health benefits parks that by extension muni golf courses like Hendricks and the Learning Links as a small youth and family golf park can provide, in an 1882 essay highlighted this fact:

“No mere brooming over the rude pavements of that period being sufficient to fully remove the chief cause of offense, the air was nearly everywhere perceptibly foul, and this to a degree often provocative, in time of epidemics, of a panicky disposition to flee the town. Where there were parks, they gave the highest assurance of safety, as well as a grateful sense of peculiarly fresh and pure air. In London, besides the better known large parks, there were, early in this century, nearly a hundred small parks—more than three times as many as we yet have in New York. The political economy of the day valued them almost exclusively because of their cleaner air, and few travelers’ stories or other general accounts of London, until lately, failed to refer to them as ‘airing grounds,’ ‘breathing places, as ‘the lungs of London,’ and so on.”

7. How did you go about selecting Stephen Kay as the architect?

When our youth learning area at Weequahic was built and funded by First Tee in 2005, Stephen Kay donated his services to the project and the County became familiar with his work. He has remained the consulting architect for Essex County over the past fifteen years, and has provided invaluable counsel in all aspects of golf course design along with agronomy and maintenance. His experience in public golf courses and coming up with practical solutions has been especially important, and he does an excellent job in articulating golf course needs and plans to the County administration.

8. How did the two of you work together?

Stephen and I worked closely on all aspects of the design, and along with Tim Christ the director of golf worked through each of the holes to develop the plan. Once we included the extra acreage at the south end of the course, we were able to create the final design. I created the concept and routing of the Road and Biarritz green on the new holes, and we worked together on every hole on the course. A lot of the design work was done in the field as the project evolved that allowed us to make some changes along the way that turned out nicely. Whenever we disagreed, Tim Christ was always the tie-breaker and deferred to him as his team would need to maintain whatever we built! It was a really fun process and we all made a great team in bringing different perspectives.

9. Is it accurate to say it’s a Banks design but because not a lot of literature exists from Banks himself, that you turned to the writings of his mentor, C.B. Macdonald, for input?

Yes, the writings of Macdonald played a major influence on the project and as we studied each hole, and considered how he and Banks might approach the design on a Modern Muni. The two chapters in Scotland’s Gift titled Inception of Ideal Golf Course and Architecture, pack so much timeless insight into just twenty-five pages of text. As Hendricks is connected to a park designed by Olmsted Brothers, I also studied the writings of Frederick Law Olmsted as well to consider how his philosophy on accessibility to open space by the masses had implications in the pursuit of high-quality public golf.

In 1850, Olmsted went on a pilgrimage to study parks both public and private in England prior to embarking on his landscape design career, much as Macdonald endeavored to study the great links of Britain at the turn of the 20th century before building National Golf Links. The principal of not just accessibility, but also the civic pride a community should have in its public open space, was described by Olmsted in his observation of Liverpool’s Birkenhead Park and embodies the spirit of how we sought to apply this same idea at Hendricks:

“Five minutes of admiration, and a few more spent in studying the manner in which art had been employed to obtain from nature so much beauty, and I was ready to admit that in democratic America, there was nothing to be of as comparable to this People’s Garden…All of this magnificent pleasure-ground is entirely, unreservedly and forever the people’s own. The poorest British peasant is as free to enjoy it in all its parts as is the British queen. More than that, the baker of Birkenhead has the pride of an OWNER in it”

Olmsted also wrote about capturing the “genius of place” and is a concept that we kept in mind as we restored what was already there through the greens by designed by Charles Banks nearly a century ago, and built on this work in bringing the classical principals to any new construction with use of unique elements like the abandoned railroad tracks or historic cherry groves adjacent to the park holes.

In the opening to his chapter on Architecture, he included a 1797 quote from Humphrey Repton who pioneered landscape architecture in England, and provided a unifying theme for our work at Hendrick as one whose style inspired the work of both Macdonald and Olmsted:

“It should appear that, instead of displaying new doctrines or furnishing novel ideas, this volume serves rather by a new method to elucidate old established principles, and to confirm long received opinions, I can only plead in my excuse that true taste, in every art, consists more in adapting tried expedients in peculiar circumstance than in that inordinate thirst after novelty, the characteristic of uncultivated minds which from the facility of inventing wild theories, without experience, are apt to suppose that taste is displayed by novelty, genius by innovation and that every change must necessarily tend to improvement.”

10. Talk to us about your idea of an ‘Ideal Muni Scale.’ How are points awarded?

As Macdonald conceived of creating his ideal course, he sought to incorporate the best features of specific holes and also assigned value to the “essential characteristics” and points awarded for each category on a hundred-point scale:

“In discussing and comparing the merits of the various courses, one is struck immediately with the futility of argument unless some basis of excellence is agreed upon, premises on which to anchor. In view of this, I have tried to enumerate all essential features of a perfect golf course in accordance with the enlightened criticism of today, and to give each of these essential characteristics a value, the sum total of which would be 100, or perfection.”

In borrowing this concept from Macdonald, we applied this idea in seeking to achieve the ideal in a modern municipal course by maximizing the potential of Hendricks, and use as a method to prioritize investment in restoration, renovation and rebuilding of course features. On Macdonald’s scale, he awarded 45 points to the ground selected for the course but as the site was a given at Hendricks, I removed it from the formula from a design perspective (although a major portion of our budget was spent on improving the infrastructure below the ground in new irrigation and extensive drainage to Improve ground conditions). With the site selection and its terrain no longer part of the calculation, the following quote by Macdonald gives us a guide and encouragement when the muni course canvas one has to work with is less than optimal, along with where to focus our efforts:

“It is true that a group of golfers cannot always find an ideal terrain where they can build a fine course, but let the property be ever so flat, one may construct an interesting course. The right length of holes can always be adopted; after that the character of the course depends upon the building of the putting greens.”

The remaining allocations for the main categories on the Ideal Muni Scale where proportionally similar (with site considerations removed) but with the merit of greens weighted more heavily and providing a full 50% of importance on the Scale. Next was bunkers and other hazards (25), Length of Hole (15) and Quality of Turf, Course Width and Tees (10). Another key theme stated by Macdonald that we constantly kept in mind along the way in seeking to avoid the monotony of many munis in their well-intentioned, but misguided attempts to avoid being overly difficult:

“Variety is not only the ‘spice of life’ but it is the very foundation of golfing architecture. Diversity in nature is universal. Let your golfing architecture mirror it. An ideal or classical course demands variety, personality, and, above all, the charm of romance.”

Below is a further breakdown of each category and how each of these areas was approached, with a quote that helped serve as a guiding principle, and illustrate how Macdonald’s design philosophy was adapted in similar pursuit of the ideal in municipal golf, through inspiration and not imitation of his work:

Greens

“Putting-greens to a golf course are what a face is to a portrait. The clothes the subject wears, the background, whether scenery or draperies – are simply accessories; the face tells the story and determines the character and quality of the portrait – whether it is good or bad. So it is in golf; you can always build a putting-green. Teeing-grounds, hazards, the fairway, rough etc., are accessories.”

This may be my favorite Macdonald quote that continued the one earlier on the character of the course, and is especially true at a muni where it is difficult to create hazards for every golfer due to such a wide range of skills. However, the one place on each hole where everyone eventually gets to is the green and with the limited budget of a public course, it is essential to devote significant resources and attention to this area. Macdonald emphasized the need for exceptional conditions and variety, giving 60% of the value in judging greens to “quality of turf.” This percentage may be even higher at a municipal course where perceived overall quality, for better or worse, is often defined by condition of the greens. Muni golfers understand budgets are limited, but will be forgiving of deficiencies in maintenance elsewhere if you give them greens that roll smoothly. Macdonald elaborated further in line with this idea while further highlighting the need for variety on the greens more specifically:

“Regarding quality, nothing induces more to the charm of the game than perfect putting greens. Some should be large, but the majority of moderate size, some flat, some hillocky, one or two at an angle; but the majority should have natural undulations, some more and others less undulating. It is absolutely essential that the turf be very fine so the ball will run perfectly true.”

Work on the greens at Hendricks was a process of restoration close to their original dimensions with contours kept intact, along with XGD drainage installed and the laying of new bentgrass sod. The average green size was increased by more 10% which added many new interesting hole locations that were lost over time to spread out wear and increase strategic interest. As stated earlier, a number of greens were reminiscent of templates found on other courses from the Macdonald school, with others with rolls and undulations consistent with his design style. The expansion of the green on #14 provides an excellent example. The hole location below would have been in greenside rough prior to the project, denying golfers this challenging hole location at the back left, as well as one at the back right with the green surface bisected by a subtle spine the allows provides much improved strategic appeal.

Of particular note is that the scale of the greens in terms of size and severity relative to other big, bold designs at the opposite end of the spectrum from these architects. The way I would describe it is that if Yale is at 100 decibels in terms of green design, Banks turned the volume down a little more than halfway at Hendricks Field. For the three new greens we built as part of the layout, replacing the holes incorporated into the Learning Links, we used this same approach to fit with the classical models present on the rest of the course. We built these greens to hit the same notes in sampling from the Macdonald design canon, but created a new arrangement with a more muted tone – making them playable and maintainable under the stress of 50,000 rounds annually and suited to a unique urban park setting.

Bunkers and Other Hazards

In looking at the original plan for the course, it appears that only about 20 bunkers were actually built when examining each hole on the ground, along with studying old aerials and as built drawings from the time of construction. For the overall project, and in considering the existing and desired strategic intent of each hole, we determined that having 25-30 bunkers on the course would fit the budget and allow for every one of them to have relevance. This meant the elimination of some, rebuilding/restoration of others to proper scale and the creation of new ones. By limiting the number, and focusing on their individual aesthetic and strategic value, we built several that will no doubt cause some golfers to complain. Another favorite quote of Macdonald explained that this kind of golfer griping is not only acceptable but desired:

“When one comes to the quality of the bunkers and other hazards we pass into the realm of much dispute and argument. Primarily bunkers should be sand-bunkers purely, not composed of gravel, stones or dirt. Whether this or that bunker is well-placed, has caused more heated arguments outside the realm of religion, than has ever been my lot to listen to. However, one may rest assured when a controversy between ‘cracks’ is hotly contested throughout the years as to whether this or that hazard is fair or properly placed, that is the kind of hazard you want and has real merit. When there is unanimous opinion that such and such hazard is perfect, one usually finds it commonplace. Fortunately, I know of no classic hole that has not its decriers.”

The modified Principal’s Nose on #15 (below) offers a fresh take on this classic design that is placed exactly where the golfer would want to play their drive. It will likely prove to be unpopular with some players, but it will certainly make everyone think in terms of how to navigate a hazard of this nature that is unusual for a municipal course. Its location also presents a fun challenge for shorter hitters in being on a direct line from tee to green for their second or third shots, and in making into one larger bunker as opposed to several small ones, allows for ease of maintenance and more formidable appearance.

In addition to bunkers, we also created grass hollows on several holes in place of bunkers that serve as an excellent hazard on a muni golf course. They provide a challenge for better golfers that is more difficult than a bunker, and for high handicappers it gives them a chance for recovery. Having fewer bunkers also allows for ease of maintenance and promotes faster pace of play that can become glacial if design elements are overly penal. Most of the restored bunkers were at greenside and encourage an approach from one side of the fairway or the other, with virtually none at the back of the greens. Bunkers of this nature offer little in the way of visual appeal, discourage daring play and reduce the element of fun.

Length of Hole

With the conversion of two and a half holes for the Learning Links offset by the acquisition of new land for those to replace them, and desire to restore the remainder of the green complexes (15 of the 18 on the course were original Banks designs) it necessitated reimagining how holes played to these greens in several instances. In doing so, we found solace in the following quote from Macdonald that such a strategy could be advantageous, while also considering how advances in technology in recent years impacted course design as in the past:

“True, nearly all courses were laid out before the advent of the Haskell ball, adding as it does about twenty yards to wood and iron. Now, while the Haskell ball has marred many excellent holes, it has made just as many indifferent ones excellent. The majority of greens committees have failed to realize this and have expended energy in devising means to lengthen every hole. It would be much better if they would shorten some, lengthen some and leave the others alone.”

In all, there were three new holes and green complexes created (holes 11, 12 and 13), five where the par of the hole changed due to shortening or lengthening of the hole (4, 6, 8, 14, 16) and the remaining ten tweaked in some way but retained roughly the same length from the middle and back tees. Another key element to the project was to add new forward tees on every hole in line with our theme of making the course more accessible and welcoming to all.

The shortening of hole #16, in reducing the distance to a range of 270-340 yards, has made this uphill hole with the Cape style green complex far more compelling. By inviting different options off the tee, it also demonstrates how the divergent skills of golfers at a muni were also kept in mind with our design approach, and exemplified varying strategies presented by the hole when played by varying levels of players. From the tee at a shade under 300 yards from the new forward tee, the green is a tempting target for long hitters, but with trees right and deep bunkers left of the putting surface presenting potential trouble.

The fairway bunker on the right side of the fairway eighty yards short of the green can either be navigated by laying up off the tee to the left (giving a poor angle to the green from the expanded area of recontoured fairway) or carried in risking more trouble. For a player with average length, the fairway in the driving zone on the preferred side of the fairway. And for one who hits a driver less than 150 yards (a larger percentage of golfers at the course), the bunker is not in play off the tee, but provides a challenging carry for the second shot and a decision after a mishit drive whether to play to the left. All levels of play in between also must make strategic choices from these distances, as well as from other tee options both shorter and longer.

In detailing his Inception of Ideal Golf Course Macdonald included his eighteen holes he would use as a guide for his designs that were also followed by Raynor and Banks. It is of note that Macdonald listed only the concept for each hole and distance, but not the par. I followed the same format below with a one or two sentence summary of each hole at Hendricks, along with its inspiration where applicable and working titles for each hole:

- 473 Yards, Alps. Uphill with a semi-blind approach after long drive carrying a bunker at corner of dogleg with punchbowl inspired green.

- 435 Yards, Garden. Downhill hole with bunkering at front right of the green favoring an approach from the left. Named after street running along the tee and honoring Garden State support.

- 173 Yards, Banks. Elevated green with bunkering at front left with mid-length one shot hole.

- 500 Yards, Reverse Redan. Lengthened hole with new bunker across fairway suggesting the 14th at St. Andrews seventy yards short of reverse redan green complex.

- 453 Yards, Swilken. A drainage ditch running across several holes is reminiscent of the burns found at St. Andrews and other links, calls for golfers to decide if they will lay back or attempt to carry it off the tee.

- 127 Yards, Reduced length from previous yardage that presented safety concerns on wayward drives for neighbors. Replaced former #11 that became part of Learning Links.

- 423 Yards, Lengthened to bring the burn more into play for longer hitters providing a strategic decision off the tee.

- 187 Yards, Redan. Restored to original length.

- 378 Yards, Double Plateau. Similar to double plateau greens with gentler slopes than other renditions of this template hole.

- 352 Yards, Creek. Resembling a mirror image of first hole at The Creek. Original plan had four bunkers across fairway that were not built, and a new one was constructed to replicate this strategy.

- 537 Yards, Rail Road. Fairway bunker at right on ideal line on lengthened hole. Green complex and abandoned railroad track in play resembling strategy of Road Hole at St. Andrews.

- 161 Yards, Biarritz. Similar to other examples at a shorter length and less severity in green contour. Bunkering at sides of green replaced by deep rough swales.

- 336 Yards, Sakura. Named in honor of the Japanese cherry blossoms at Branch Brook Park bordering this hole as reclaimed golf space. Suggested by 6th at Forsgate and 4th at St. Andrews with mound at front left of green partially obscuring green surface.

- 218 Yards, Original green from Banks layout converted from par four into the longest one-shot hole on the course.

- 385 Yards, Principal’s Nose. Defining feature set in right center of fairway at location of ideal drive or to be carried with second or third shot by shorter hitters.

- 287 Yards, Cape. Similar but less severe version of 2nd at Yale, with cape green jutting out over a bunker. New fairway bunker on direct line to green on right side of fairway. Hole plays up to 340 yards but most interesting as risk/reward drivable hole.

- 147 Yards, Eden. Expanded green complex as on many others to original dimensions for this classic template hole.

- 445 Yard, Road Home. Resembling Road Hole green complex on the final hole of the course.

The yardage for the course when played from these tee locations provides excellent variety and is the same total suggested by Macdonald in Scotland’s Gift at 6,017 yards (the course can be extended by about an additional two hundred or so yards as with his). These distances roughly approximate what I feel is the most interesting for each hole, with maximum flexibility of enjoyment for all levels of golfers. The course’s six par threes, never playing consecutively and each requiring a different club as outlined with this setup, offer a fun challenge when combined with the rest of the course through its thought-provoking hazards. For long hitters it might play as a par 68 from these tees (the card says par 70) and for those who average closer to 150 yards with the driver (much closer to the average of amateur men and women) it may be more like a par of 80. Far too much emphasis it put on “championship” course length and conditioning standards that are particularly problematic when applied to a muni course, and our hope is that Hendricks can help to positively demonstrate this principle.

Quality of Turf, Course Width and Tees

With a lower maintenance budgets than private clubs, it is impossible to offer muni golfers conditions at the highest level, but through the infrastructure work at Hendricks this up-front investment will pay dividends in the long run to provide quality playing surfaces. Macdonald stated that “for quality turf through the fair green, there is no excuse for its not being good enough.” With limited funds we must define “good enough” a bit differently, and to achieve this it is especially important to have skilled course management with resources at their disposal with focused attention on high traffic areas. Part of what will allow this to happen is the conversion of about ten acres of formerly mowed turf into native areas, and through this more sustainable approach, also providing a presentation more in line with the principal of Olmsted to avoid “excess ornamentation.”

Macdonald lamented the widening of courses, and desired tees to be in close proximity to greens. While our design avoids long walks between greens and tees, on a muni with heavy play, it is imperative to have ample room to maintain safety. We achieved this goal in our redesign of several holes, and with the new tees, provided much greater variety and options for all level of golfers. Many existing forward tees were an afterthought and in poor condition, and we ensured that this was not the case in building new ones so every golfer has a real teeing ground to play from.

11. Please walk us through before and after photographs of three holes that were greatly improved.

The previous 2nd hole (now #11 after the project is complete) was a very mundane par four with featureless fairway and one of many par fours on the course in the 370-410 range on the course. As we examined the hole and potential in how to use the additional land to gain three additional holes, there were a number of configurations considered. After weighing various options, I felt that the best way to utilize a portion of this space was to extend this hole additional 150 yards as the course lacked a true three shot hole, and take advantage of the abandoned rail line as a strategic hazard. Below is a photograph of the previous hole corridor that was lengthened and left of the old (poorly draining) green:

|

Off the tee, we added a fairway bunker in the driving zone on the right side similar to many Road Holes as a rendition of the rail sheds at St. Andrews that must be carried or avoided to have a chance at reaching the green in two. Playing to the left either on the drive or second shot leads to being blocked out on a direct line to the green by trees, and also forces one to play over the representation of the Road bunker at the front left of the green (softened from the original as Banks did with the rest of the course).

The last hundred yards of the lengthened hole bring the abandoned tracks into play, at an angle similar to the road at St. Andrews, or the bunkering on #7 at the National Golf Links. We removed a number of small trees and brush along the rail line, along with debris in cleaning up this area of former park, while preserving many of the larger trees including one at the back at the back of the green that serves as a guidepost.

|

|

With short grass continuing off the back of #11, the green seamless transitions to the #12 tee of our new Biarritz. We originally considered building a Short hole at this location but after tree clearing and seeing that we had a bit more length, decided on a rendition of the Biarritz that would be more unique and was a missing element on the course. The green is roughly 10,000 square feet and sixty yards from front to back, with the signature swale in the middle that is much shallower that other versions of the hole, and allows a fun hole location in the lowest middle section. Unlike a similar Biarritz we had built at Mosholu some fifteen years ago, the version of the green at Branch Brook is fully visible from the tee and has no bunkers on either side. We instead built rough hollows below the green surface as a more suitable muni hazard that is difficult for better golfers, but manageable for beginners. This approach also seemed fitting as it is only hole constructed entirely within the park where bunkers felt out of place. Nearly half of the new area remained in a natural park state with the addition of cherry blossom trees as a unifying theme between Hendricks and Branch Brook.

|

|

|

Another hole that was improved significantly was former #12 which will play as #4 on the new course configuration. The strongest feature of the hole, as with many at Hendricks prior to the project, was the Reverse Redan green complex that encourages a shot coming in from the left side of the fairway. At roughly 380 yards from the back tee previously, there was very little interest off the tee and no decisions to be made. The bunker at the front right of the green had deteriorated badly, as had the bunkering at the back left that was far too narrow in scale. The photograph below was taken right after a handful of large trees were removed beyond the green that prevented proper sunlight and the paths in this area were a complete mess.

|

With the creation of the Learning Links and conversion of previous #15 into a par three, it allowed for the tee on this hole to be extended back to turn the hole to a par five playing up to 510 yards. The tee shot was improved to encourage a right to left shape off the tee with a long drive offering a choice for the second shot encouraging on a left to right shot (or for higher handicappers their third or fourth) of whether to carry the bunker that extends across the fairway about fifty yards short of the green. While technically a forced carry, with a bunker face more severe on the left side for those seeking the optimal line to the green, there is room in the rough to play around to the right. The rough will be maintained at a very manageable length providing a longer path around but will result in the following shot bringing the greenside bunker more into play and making the green tougher to hold with a poor angle from longer grass. Macdonald noted that several hazards of this nature should be included in his ideal links, and we adapted the concept to Hendricks:

“To my mind, an ideal course should have at least six bold bunkers like the Alps at Prestwick, the Ninth and Brancaster, Sahara or Maiden (I approve only of the Maiden as to bunkering, not a hole) at Sandwich, and the Sixteenth at Littlestone. Such bold bunkers should be at the end of a two-shot hole or a very long carry from the tee. Further, I believe the course would be improved by opening the fair green to one side or the other, giving short or timid players an opportunity to play around the hazard if so desired, but, of course, properly penalized by loss of distance for so playing.”

12. In addition to Stephen and you, who else deserves a shout-out for making this happen?

As mentioned before, Director of Golf Tim Christ had established more than a decade of credibility through expert management and gave the County confidence to pursue the project. The project would have never happened without him. His daily oversight and management of the job (thanks to Turco Golf who was the contractor as well) will allow it to be completed in less than 10 months in spite of a difficult winter. Tim had worked at some of the finest clubs in the country as an assistant at Merion and Pine Valley, and as head superintendent at Metedeconk National. Just as Banks was able to turn down the volume with his design features to fit a muni, so too as Tim and his maintenance team in properly adjusting to make the most of available resources at the three County courses to present excellent conditions.

He completely revamped the entire operation, and put an excellent former assistant from an area private club as the super to run maintenance at each of the three courses – each of whom are now outstanding supers in their own right. I have been fortunate to work with many terrific people in my time in golf, but I don’t think there is a single one I have ever met who is as well-suited, skilled and dedicated to their job than Tim. Jimmy Aguirre, the golf course superintendent at Hendricks, has also done a fantastic job in leading his crew throughout the project, and I am certain will do great work in maintaining the course once everything is complete.

Many of our First Tee supporters gave me great encouragement throughout the project, and in addition to the Ryan family, Barry Hyde, Steven Wilf and Joe Kusnan were particularly helpful in giving their perspective and made many visits throughout the course of the project. The chairman of our First Tee Chapter, Ken Whitney, deserves a lot of credit in allowing me to pursue this project as part of my work in developing this model First Tee Campus, and for his extraordinary generosity and leadership of our Chapter. And from the First Tee staff, Matt Rawitzer who succeeded me as Executive Director, provided great input as an excellent player and was a constant sounding board for me throughout the project. Katie Rudolph also assisted through her longstanding work and relationships with everyone in Essex, as well as suggestions for the Learning Links design to best teach our students. Our friends at the USGA including Rand Jerris, Hunki Yun and Chris DeToro were also very supportive and reflect the organization’s commitment to sustainable public golf and will continue to be a resource as we look ahead.

In addition to County Executive DiVincenzo and Senator Ruiz, many other individuals from Essex provided support along the way most notably Chief of Staff Phil Alagia, Parks Director Dan Salvante and Public Works Project Manager Willie Derricotte. A special thanks also goes to the County Commissioners, or legislative body for Essex, who ultimately approved the project and Assemblywoman Eliana Pintor Marin also helped to gain funding through the state legislature.

13. What advice would you offer to other municipal courses looking to enhance their offerings? Any do’s and don’ts that you learned through trial and error?

The biggest piece of advice is to make sure that there is sufficient funding to address infrastructure issues and to be ambitious in terms of seeking funding; communicating how it will truly result in significant public benefit for every member of the community. The messaging must be that this is not that these are not just for golfers, but are parks and public works projects that promote accessible open space for all worthy of public funding. Making major, long term capital investments also helps to ensure that these properties will remain golf courses in the perpetuity, and not be on the chopping block when budget inevitably get squeezed. Changing the narrative in this way takes the pressure of the need for a muni course to maintain profitability if it is presented in these terms, and opens up additional funding sources and philanthropic giving.

Parks and roads are not expected to make money, but golf is when it comes to municipal budgeting. When combined with programs like First Tee where there is a tangible, meaningful community impact it further enhances the mission. Gaining government support from the key funding sources and administration officials allows them to all take ownership of the work, and provides their constituents with a resource that promotes wealth and wellness in a way that is celebrated across the spectrum. It is politically impossible to be against parks and programs promoting wellness and education for youth, but as muni golf proponents (and as done by the excellent work of National Links Trust and others more recently) we need to also generate awareness from a broader audience to make this case.

14. When did Hendricks Field become a First Tee site?

First Tee students have had access to the Hendricks Field Course at discounted rates since we started the program in 2005, but the opening of the Learning Center to be completed in late 2021 or early 2022 will mark the true beginning of Hendricks Field as a First Tee Campus. This is defined by a full-time director and staff teaching year-round with a full complement of both golf and education programs. The vast majority of funding for the project came from the state of New Jersey and the fact that First Tee will be conducting programs in perpetuity at this site allowed for investment of this magnitude using public funds.

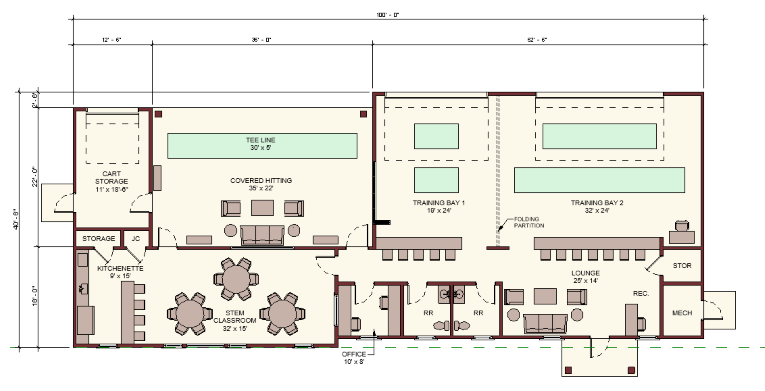

A huge thank you must go to the architectural firm of Rogers McCagg who have now designed several learning center projects for First Tee Metropolitan New York at rates well below their typical fees. They specialize in golf clubhouses, schools, sports/recreation facilities and community buildings and our Learning Center at Hendricks Field has elements of all of these. Their private clients include Shinnecock Hills and Winged Foot, with their golf training center at St. Andrews Golf Club in Westchester serving as an inspiration for our work at Hendricks.

|

|

With roughly 4,000 square feet of indoor and outdoor space, there are several hitting bays that can be used for indoor hitting into a net with advanced technology, or hitting out of garage doors that open onto the Learning Links. There is office space, restrooms and a large classroom that will enable STEM focused learning and other activities. This is connected to a kitchen and seating that opens to a covered tee line/porch for additional practice and lounge space. There is great flow between indoors and outdoors, and seating near the facility entrance and at bar stools facing the hitting bays where students, parents and friends can watch and gather.

|

Mike Mikolajczyk has been our lead architect for all of our projects at the Wilf Learning Center at Plainfield West 9, Weequahic clubhouse renovations and now Hendricks Field. Their entire team is outstanding to work with and I cannot speak highly enough about their creativity, talent and generosity. We estimate that this Campus will serve at least 500 students each year, and is a short par four walk from the Belleville Rec Center in what will become a community showpiece.

15. Talk about the 3 hole practice area now known as “The Learning Links” area.

The Learning Links offers a great deal of flexibility as it can be used as short driving range when hitting out from the Learning Center with two target greens, a three-hole course with holes ranging from 70-160 yards, or for practice on and around individual greens. It is comprised of two greens that were formerly holes #11 and 14, along with the first half of what was #15. A third green was built on former #15 in the shape of a Biarritz with a mound at the back right to provide a place for students to sit during lessons. The elongated nature of the green offers an excellent way for a group of students to line up and work on chipping/pitching, while a long, rectangular bunker at the front left of the former #14 will allow the same for bunker practice and clinics. Extensive fairway allows for practice and creation of many different options for distance and angles with fun competitions like HORSE.

When played as a three-hole course, the holes evoke classic Macdonald design principles with a Short, Biarritz and Redan in their configuration giving youth an introduction to classic design. The eight-acre area is situated on a busy road with the Learning Center visible to the community with its own dedicated parking lot. The Campus area is defined by a split rail fence to give it a more pastoral feeling and while connected to the rest of the course, is its own separate area with a distinct purpose for youth. In reversing the nines of the course, it has allowed the more dramatic holes to be on the back nine, and also for the holes nearest the Learning Links to open up for use of the kids after golfers are through the front nine late in the day. This will allow youth golfers to take these over at twilight and have additional area to learn and practice, with a community gathering place for students and families in the last couple of hours before sunset. Below are two images: the top image is from the street that shows the parking lot and learning center under construction, with the bottom image is from the golf course.

|

|

16. The course reopens late this month. How many rounds do you expect over the next 12 month period, and what is the green fee for a) residents of Essex County and b) non-residents?

We expect to have 45,000-50,000 rounds over the next 12 months, and rates for residents will range from $21-37, and $31-52 for non-residents

17. Tell us about your new role at Western Golf Association/Evans Scholars Foundation and how this program can also help in improving accessibility to the game.

Evans Scholars was established in 1930 to provide college scholarships to youth caddies in financial need with strong academics, caddie experience and character. The historical core of the program is in the Midwest with the Western Golf Association based in Chicago, but has expanded in recent years to the West Coast and now the East. Evans has a huge network of supporters and scholars served, with more than 11,000 alumni and nearly 1,100 Scholars currently in college. A unique aspect of Evans is that most of the 20 partner universities have a dedicated scholar house on campus where all of those on scholarship live together as part of a community.

My responsibility will be two-fold in leading the East Region: 1) promoting youth caddie programs that in many cases have waned over the past few decades through recruitment, training and development, and 2) fundraising to support more Evans Scholars, partner to grow local caddie scholarship funds and develop new houses at flagship universities in the East. University of Maryland is already under development thanks to the membership at Caves Valley getting behind it (along with the BMW Championship that will be there this summer) with Rutgers in New Jersey being another school on the radar for expansion and growth in the future.

With so much of my work in New Jersey over the past fifteen years through First Tee, one of my goals will be for their programs in Newark and Plainfield to provide a feeder for youth to have the opportunity to caddie as teens and gain scholarships. This will help to create lifelong golfers, and provide an amazing educational opportunity. Evans has also pioneered subsidized caddie programs at munis that they started at Jackson Park in Chicago, and with a potential for a similar program at Hendricks down the road. Students would be trained and supported through a caddie prep curriculum through high school, and then go on to work at private clubs in the area, participating in an academic/leadership program and eventually becoming eligible for Evans and New Jersey State Golf Association scholarships.

The NJSGA is truly dedicated to promoting youth caddying through their tradition of service, and we are working in partnership with them at Evans as a model to expand in the East. Through this collaboration, we will be able to give more young people the chance to gain a great college education with no debt, and the new First Tee Campus at Hendricks will be place for kids in financial need to start this journey to improve their lives and communities through the game.

18. What is next up for Essex County now that Hendricks is nearing completion?

With major improvements at Weequahic and Hendricks being completed, we hope that the enthusiasm and success of these projects will allow for new funding for a full bunker and green restoration at Francis Byrne Golf Course. Like Hendricks, this former West Course of Essex County CC was designed by Banks after Raynor’s passing during the design process. Since the 2007 project to address some major infrastructure needs along with design improvements (restoration of the alternate fairway on the Bottle Hole was a specific highlight) and additional upgrades have been made high quality conditions presented by Chris Krno as superintendent. Byrne has an excellent layout with some extremely bold bunkers and greens if rebuilt and expanded fully to scale. With the proposed execution of a master plan of this nature at Byrne, it will give golfers in Essex County and surrounding communities three distinct courses with their own unique personalities that provide fun, challenge and affordability that is within everyone’s reach.