Feature Interview with Chris Clouser

April, 2006

Chris Clouser is a project manager/financial analyst for a REIT in Indianapolis, Indiana who writes in his spare time. He has two children, Emily and Jason and a wonderfully (!) understanding wife named Danielle. Chris was introduced to golf when his father bought him a set of Northwestern golf clubs for a junior high graduation gift over twenty years ago. He has studied golf course architecture as a hobby for ten years and wrote the The Midwest Associate: The Life and Work of Perry Duke Maxwell after coming in contact with Maxwell’s family, including the late Dora Harrison, Perry’s last surviving child.

1. How did Perry Maxwell become a golf course architect?

His introduction to golf course designing was a multiple step process. Initially the thought of Maxwell designing a golf course was brought forward by his wife after reading an article in Scribners Magazine. In 1914 they purchased a large piece of land north of Ardmore. Perry decided to build four holes in the portion of the homesite nearest their house. Over the next five years he would complete a nine hole routing and be involved in the formation of the Dornick Hills Country Club. In 1917 his role as Vice-President of the Ardmore National Bank was eliminated when it consolidated with the First National Bank of Ardmore. Then in 1919 his wife died from appendicitis. After the funeral he decided to take up the profession that his wife had pushed him towards. It was then that he went to Scotland and did a study tour of several courses. When he came back he began work on completing Dornick Hills and started to take on other projects.

2. What drove him?

Maxwell was fairly wealthy due to some wise land and oil investments during the oil boom in Oklahoma, but he still felt like he needed to work and provide for his family of three daughters and one son. One of the things that was over his head was a promise to send their children to the finest schools in the country. All of the girls attended Abbot Academy and went on to college. Perry’s only son, Press, would go on to eventually graduate from Dartmouth. Once the Depression hit it was obvious that he needed to continue his occupation. He was one of the few architects in the country that actually thrived during the depression, mostly through renovation and redesign work.

3. Is there any telling if growing up in windy Oklahoma influenced his designs?

Maxwell actually grew up in Kentucky and moved to Oklahoma in 1903. This was to combat his health issues from a case of tuberculosis. I think that he admired the linksland courses of Scotland and how they incorporated the terrain and its natural movement into the design. He was also very influenced by the ‘National School of Design’ and Charles Blair Macdonald. I would say that he definately took the wind into consideration in his designs, but to say it influenced what he did when laying out a course would be a stretch. Maxwell looked first at what the terrain was doing and tried to work with the higher elevation points on the terrain to provide elevated green locations. His main thought, especially in Oklahoma, was drainage due to the heavy clay soils. Then he would use template holes that would fit in with the terrain accordingly and then lay out the remainder of the course based on what the terrain gave him.

4. What were other key influences on Maxwell relating to his architecture?

Early on in his career there were two main inspirations, Scotland and Charles Blair Macdonald. As mentioned in the previous question, the courses in Scotland influenced how he routed the course and found the holes in the terrain. Macdonald influenced him through his ‘Ideal Course’ concept and the use of template holes. The first great course that he really studied was the National and this allowed Maxwell to study holes like the Redan, Short, Leven, Eden and others and how to incorporate the characteristics into the terrain. So whenever he would see a similar landform he would adapt one of these holes. Macdonald also influenced him by the use of an engineer to do his construction. In Macdonald’s case this was Seth Raynor. For Maxwell it was his brother-in-law Dean Woods. Woods worked with Maxwell starting with Twin Hills in Oklahoma City and throughout the Great Depression.

5. How did his work evolve over the course of his career?

Maxwell’s career really involved three styles. The first was a much more template driven style that he used on only two courses. By this I mean that many of the holes were template versions of the famous holes he studied at the National. The only courses that appeared to have this style were the first and last courses of his career, Dornick Hills and Oak Cliff in Dallas. Beyond that he had two other styles that seemed to differenciate themselves based on where he was doing his work. Maxwell had a much more artistic flair to his work when he was given ideal terrain such as Prairie Dunes or Crystal Downs. This same style proliferated many of his works in the 1930s, such as Old Town and some of his renovation work during the period. Some of this influence was clearly from his partnership with Alister Mackenzie. The other style that he adapted is probably what most people associate with him. A simple style that just used the movement of the terrain and the lack of unnatural hazards with simpler shapes. This was what he used primarily in Oklahoma in the early and later parts of his career when he was primarily employed in the Sooner state. I believe this was a conscious choice to use this style as in the midst of his ‘artistic’ period he did the work at Southern Hills in this simpler style while all of his other work in the period had more flair to it.

6. More than one critic considers the interior contours at his original nine holes at Prairie Dunes to be the best in the game – where did he develop such talent?

Maxwell’s green contours evolved over his career. Early in Oklahoma many of his greens only featured very subtle contouring but some noticeable slopes in one direction or another. This was to deal with the drainage issue. After his first few designs at Dornick and Twin Hills and a few others, he began to experiment with more contouring. The greens at Muskogee and Hillcrest in Oklahoma are prime examples of this slight shift. After that he began to get more bold and used multiple methods of contouring such as spines, swales and bumps on the interior of the greens. The best example of this shift is at the Oklahoma City Golf & Country Club. His next large project was at Crystal Downs with Mackenzie. I think the chance to work with sandy soil opened his eyes to what he could do and he started experimenting even more bold contours. He lived on the site for six months at a time over three years and during that time I think is when he mastered the concepts he was trying to achieve. Naturally, the next time he had the chance to work with sandy soil, he would achieve amazing results. That is what happened at Prairie Dunes.

7. Where are his second best set of greens?

I think you could have a couple of courses really qualify. I think his second best set of greens was actually at Prairie Dunes. I believe the set at Old Town was even more impressive when he completed those. They make some of the greens in Hutchinson seem tame. Crystal Downs would also be among the top of the list.

8. What was his relationship to Alister MacKenzie?

Maxwell and Mackenzie were good friends. In 1919, when Maxwell went to Scotland, he met Mackenzie for the first time at St. Andrews. Mackenzie was the consulting architect at the Old Course for the 1921 Open Championship. They discussed a possible partnership at that time. When Mackenzie made his first trip across America, Maxwell got him on at the Melrose Country Club as a consultant and their partnership began. As he traveled across the country to California, Mackenzie also stopped in Oklahoma to tour Twin Hills in Oklahoma City (Mackenzie rated the course above the Lido, Garden City and the National), the site of the Oklahoma City project (which was contracted under the Mackenzie/Maxwell umbrella) and went to Ardmore and saw Dornick Hills and met with Maxwell’s family. They stayed in touch enough to keep up on business matters and in 1928 they met in Grand Rapids, Michigan to take on the Crystal Downs contract. After the contract was taken Mackenzie also took the University of Michigan contract. Mackenzie was impressed with Maxwell’s work. He was so impressed that he actually let Maxwell create the initial routing of the U of M course in 1929. After the Michigan project they would only meet one more time, to discuss the Ohio State course project in Columbus, Ohio. After the meetings and Mackenzie went back to California, they never talked again.

9. How did they work together at Crystal Downs?

Maxwell and Mackenzie were heavily involved in the early stages of the Crystal Downs project. But Mackenzie did not stay on the site for very long. I believe Tom Doak mentions in his wonderful Mackenzie biography that they were both there long enough for Mackenzie to help with the construction of the sixth and seventh greens. Mackenzie was the primary designer of the front nine. He probably left Maxwell with some preliminary ideas for the back nine. Maxwell would stay on the site for most of the next six months and finish construction of the first nine holes. The second nine holes were cleared and construction began the next year. Then in the third year the construction of the back nine was completed.

10. How did he come to work at Augusta National?

Maxwell had not ever been to Augusta prior to attending the Masters in 1936. During the tournament he met Bobby Jones and Clifford Roberts. Soon afterwards he was invited to come to Augusta and do some alterations to the course that the professionals were suggesting to make the course more difficult and suitable for a professional tournament.

11. What specifically did he do there?

Maxwell did alterations to ten holes over a two year period in 1937 and 1938. The most famous are the movement and construction of new greens on holes seven and ten. He altered the bunkering on holes one, five and seventeen. He also reconstructed the greens on holes three, four and six. The last two holes that he touched are much less recognized. Maxwell altered the eighteenth hole to be a three tier geen with the bottom tier extending down between the bunkering but not quite to the extent of Mackenzie’s original putting surface. This green was rebuilt by RTJ after a three putt on the green cost Ben Hogan the championship in the mid 1940s. The other hole that Maxwell touched was the ninth. He eliminated the boomerang green that existed and constructed a new green complex that is almost identical to the one that currently exists. Almost all of these holes have been touched since then, but much of what Maxwell did remains, perhaps even more than what Mackenzie left.

12. What specifically did he do at Colonial Country Club in Forth Worth, TX?

The Colonial project was the brainstorm of Marvin Leonard. He wanted the best course in Texas and sought out the ideas of John Bredemus and Perry Maxwell. They each submitted five routings for the course and Leonard took the best ideas from the submissions. The course was then constructed. One of the construction leads was Dean Woods, Maxwell’s construction expert and brother-in-law. Bredemus did not hang around after the design submission stage, but Maxwell was constantly in touch and around the site and gave some design advice during the construction. When Leonard was awarded with the 1941 US Open, he purchased some additional land to expand the course and construct three new holes. He hired Maxwell to do this and Maxwell laid out and constructed what is now referred to as the Horrible Horseshoe. While there Maxwell also rebuilt most of the greens and redid all of the bunkering on the course to prepare the course for the 1941 US Open. He stayed on as a consultant for the Open and Dean Woods was on the championship committee.

The one shot 8th at Colonial Country Club was a stunner back in Maxwell's day. This photograph was taken in 1941.

13. What Maxwell course would benefit the most today from a restoration? What special/unique features would be uncovered during such a process?

Easily the course that would benefit the most from a restoration today would be Dornick Hills. What is there today and what Maxwell constructed are like night and day. You can still see much of his work in the ground as you walk the course. It is just sitting there begging to be brought back out. It was also such a departure from anything else at the time. He used large bunkers and waste areas with imaginative hole layouts. It would also point out the style that he used was much more in line with CB Macdonald’s philosophy during his early period of design. Also recapturing some of those early green designs and contours would be fabulous. For example the thirteenth was a massive green that contained three tiers and was much more striking that what currently exists on the site. Southern Hills would be my next choice if one wanted a much more high-profile project. If for no other reason to recreate the second hole to what Maxwell wanted it to be.

The 10th at Dornick Hills right after construction was completed.

14. Do you have another Maxwell design that could be considered a hidden gem and that deserves more recognition? What features does/did it possess that you admire so much?

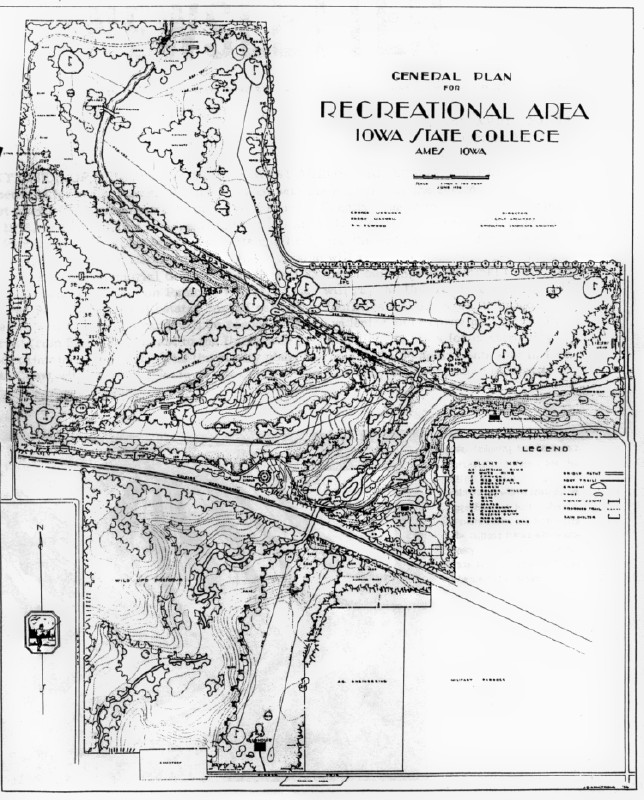

I think that the bulk of Maxwell’s work could be considered hidden gems. Unlike a William Flynn, he did not have a huge populace to play his majestic designs in a metropolitan area like Phialdelphia that afforded him a lot of exposure for his work. He built courses in the ‘wildnerness’ of Oklahoma, Texas and Kansas. I guess if I had to pick a few of his works I would have to go with one from each of what I term the ‘eras’ of his career. From the early years it would be difficult to pick one, but I would probably use Muskogee as the best example. The site had three major features, natural creek beds that had dried up over time, an oddshaped lake and a center point to the site that was also the highest point. Maxwell used the natural features to provide the drama of the round. The creek beds were the natural defenses he employed on the front side and he used the lake on five of the holes on the back side of the course. During the middle part of his career, I would say the easy choice would be at the Iowa State golf course, now called Veenker Memorial in Ames. As seen on the routing, the course did not contain two loops of nine holes as most of his work did over his career. The first and eighteenth were put together to mimic the opening and closing holes at St. Andrews, complete with a Valley of Sin type of feature on the last. The rest of the course was routed around the creek that ran through the course. Most of these holes survive today and provide a quaint layout with some interesting holes. The last period of his career, where he worked mostly with Press, would be a little more difficult as most of these courses have been altered significantly, but I would say the best example remaining intact is the Oakwood Country Club in Enid, Oklahoma. The front half of the course works over some mildly contoured land with some amazing green sites. But starting with the ninth you see a new piece of property it seems with natural hills and small valleys that allow for some interesting holes and contains some of the most difficult greens in Maxwell’s career to putt on. I would say that the stretch of holes nine through thirteen at Oakwood is among the best that Maxwell designed. But as I said there were several of these hidden gems throughout his career. Hillcrest in Bartlesville and Hardscrabble in Fort Smith and several others throughout his career would probably be classified with hidden gem status if only they were located somewhere besides the ‘wildnerness’ of the Great Plains.

A copy of the original routing of Veenker Memorial in Ames, Iowa.

15. Where do you place Maxwell among the game’s great architects?

I think Maxwell is in the top ten of American architects in history. I won’t go so far as to say that he was the best ever, but his body of work is impressive, when one also considers the amount of redesign and renovation work that he did. He was also the only designer that thrived during the Depression. I just think he gets overlooked because his work is primarily in the Great Plains instead of Philadelphia or New York like some of his contemporaries.

16. How and where did Perry introduce his son Press into the field of golf course architecture?

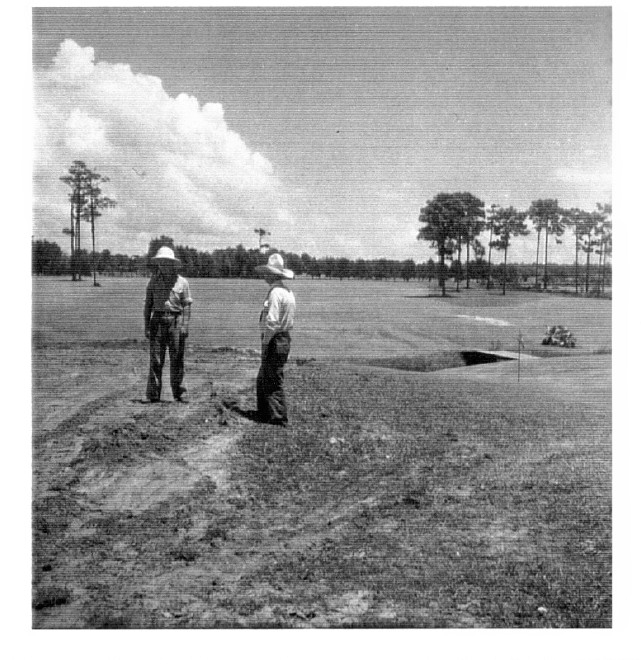

Press actually wanted to be a golf course architect when he was a child. He wanted to do what his father did and to carry on the family business. Press worked on several sites doing jobs like digging out bunkers and building tee boxes in the late 20s and early 30s. In 1935 Press actually was a foreman on the Southern Hills job and oversaw the work of several crews around the course. After Press returned from World War II, he took over the construction duties of his father’s courses. The first course he and his father co-designed was at the Grand Hotel in Pointe Clear, Alabama. Press would have this responsibility for the remainder of Perry’s career. Then when Perry passed away his son took over the reigns of the business.

Perry and Press at Lakewood Country Club in 1945.

17. Please speak as to the quality of Press’s body of work.

I have not seen a lot of Press’ work as a large chunk of it is in Colorado and spread around Texas. But from I have seen, I think he has a solid understanding of what his father wanted to do at the green end of his designs, but could never master it. His greens at Prairie Dunes are nice, but for some reason they don’t match up to his father’s work. What I have seen though from Press is a different philosophy in how to lay out holes and he used concepts that were very much like most of his contemporaries.

18. As a first time author, what was the publication process like?

The idea of the book came from talking with Maxwell’s family and once I began writing I thought it was just too large to not have some sort of book. The hours I poured into this were countless, but it started in earnest on Labor Day weekend of 2001 with a trip to Oklahoma. Through a series of interviews with family members and people at clubs and reviewing old newspaper articles I was able to piece it all together.

Since I’m not a professional writer with the access of a Brad Klein, I felt like I had to have a product that was near completion before going to any publishers. That took almost three years from inception in the middle of 2001 until early 2004. Once I had something of substance to go around, I began soliciting the book to different publishing houses that had any history with successful golf books or with a possible interest in Perry Maxwell. This basically consisted of sending out a large number of letters, concept pieces and even a couple of rough drafts of the book to people that even thought it might be something they would want to look at. Unfortunately, it got turned down by almost all of them as they felt there was not enough of an audience for the book. Thus they couldn’t afford to produce it without seeing sufficient returns. Aside from turning me down almost all of them responded with positive feedback about the book, but just that they couldn’t take the risk of publishing it. So that helped keep me going knowing I was onto something.

But one publisher expressed some interest and we even had an understanding, but things fell apart on both ends of the deal. But that one exposure to a publisher opened my eyes to the whole editing and culling process. I don’t care what anyone says – the editing process is a pain! When they are done with your work you wonder if you wrote anything of substance. After picking my ego up from the floor I realized my work had not been in vain, it just needed some sprucing up. So I touched up the book and then refreshed the presentation of the book a little and started on the warpath again. This time getting turned down by all of the same people and then some new ones that had entered the industry since my last attempt at pitching the book. Well after almost two years of searching I came across Trafford Publishing. After some initial questions of them and trying to get the layout in some manner that I felt still conveyed the message it went to the printer. They are literally a print on demand service that with a one time fee will sell the book through their website and print and distribute it world wide. The best part of the deal, aside from the royalties of course, is that I retain the copyright so I can always stop the presses if some publisher decides they want to take a shot at a book on Perry Maxwell.

If I ever decide to write another book, I hope having something already out there with my name on it will make it a little easier to get the work published by a known publishing house.

The cover of Chris Clouser's just published book.

19. How does one acquire your book?

The Midwest Associate: The Life and Work of Perry Duke Maxwell can be ordered from www.trafford.com/05-2642 .

The End