Feature Interview with Bobby Weed

April 2015

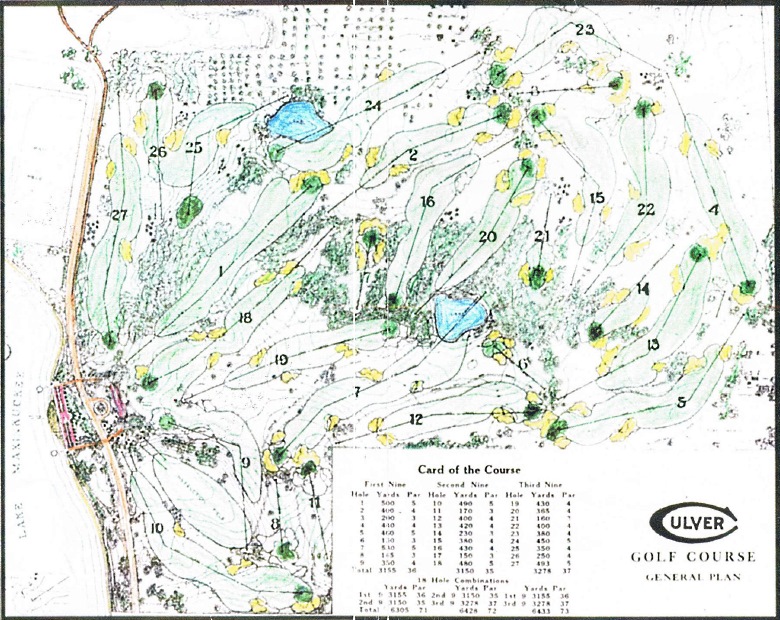

1. Please update us on your work at the nine hole Culver Academy by Langford and Moreau. To me, it’s the best nine hole course in the country.

What a gem of a layout! We agree with your assessment. Properly maintained, it’s hard for me to imagine a better nine-hole layout in the nation. Not only does each hole have its own uniqueness with big, bold features, it has arguably the most interesting set of green complexes–making it the best nine-hole layout I have seen in the country. I have not yet seen the Dunes Club, but I think it’s interesting that these two courses are located within hours of each other.

The project has been in the works for a number of years and is now completed and growing-in. On the course, the project was as archeological as any I’ve been involved in. Primarily, we restored the sand bunkers to their original locations and are working to widen the greens and fairways out to their original limits. We expanded and re-levelled the tees, and added a few new forward tee locations. We had the benefit of some historical aerial imagery, but really, it was pretty apparent on the ground where everything was. In addition, we constructed a new practice facility on some unused ground central to the layout.

Old aerials increasingly play a role in restoration work. In the case of Culver, the one above helped highlight the dramatic bunkering that had been lost over time.

Perhaps most importantly, we helped structure a new maintenance plan with the Academy. The project’s benefactors have endowed a full time superintendent position, who is now on board and a package of new maintenance equipment is on its way. This coming year the course will see more agronomic attention than in the past 50 years, I would say.

Along the way, we have met some great folks associated with Culver and have been impressed with the level of passion and conviction these alumnae share regarding the school and their amenities. The golf course will be a great recruiting tool for young golfers at Culver.

Pete Dye has long said that the works of Langford and Moreau were some of the best—so to have the opportunity to work with the Academy on such a noted layout has been a great assignment. Chris Monti from our office and Tom Mead assisted on the project as well.

During the project, I came to wonder if Langford and Moreau had been more prolific along the eastern seaboard instead of mostly in the heartland, whether this duo might have been held in closer regard, more along the lines of Donald Ross, perhaps.

2. Pete Dye was famously influenced by Seth Raynor and there is a lot of Raynor/Macdonald design principles found in Langford and Moreau’s work. As you worked at Culver, what did you come to appreciate about their design?

There is no question similarities exist between all these artisans. The expansive, large features that they built (i.e. greens, bunkers—both size and depth) and the angles to the line of play that these features are set at, all come to mind. The quirkiness of the green contours and how the routing lays on the ground are similar, as well.

The nine holes at Culver were part of a 27 hole layout, a map of which exists. From what I understand, the duo received direction to build ‘the best 9’ first, with the remaining holes to follow. The nine that were built fit that directive perfectly. Chris and I spent a little time looking over the ground for the remaining 18 – which is largely undeveloped – and it did not seem as compelling as the land that the constructed holes sit on.

I think I came to appreciate the quality of the routing and the economy and effectiveness of the constructed features. I was also a bit amazed at the size of the bunkers and how they could have been afforded during the original construction. There must have been an inexpensive local source of sand at the time!

3. What did you learn working for Pete Dye?

Enough– that a number of folks have suggested that I write a book one day. In short, I learned about how to treat others, to be respectful and have fun along the way, all while exhibiting such passion that is hard to quantify. Pete has an unyielding drive to create great golf courses and is successful because he puts so much effort and heart into his designs. He is not afraid to admit his mistakes and often builds and rebuilds a hole until he is totally satisfied. He taught me that it’s okay to make changes, multiple times if necessary. One early lesson was he never chastised anyone for ‘roughing in some features’ that he might ultimately completely change—he would simply say, “lets rub on it a bit more”. Pete always said the saddest day on site, was the day the grassing crew showed up…

4. Glen Mills opened in 2001 on the campus of a boy’s school and is a daily fee course. The 14th hole is called Redan and another green features the famous Biarritz swale. How did these Macdonald/Raynor template features come to be included in your final design?

While these particular named holes/features are well-noted, the one-shotter at the 14th hole at Glen Mills was simply a right to left angle, slightly uphill and the contours worked. It was never a case where I thought about replicating the Redan hole, sometimes it just happens and if the hole has some of the Redan characteristic, that’s okay. Golf courses should ebb and flow with regards to difficulty, and this can influence features, greens, contours, and length—during construction.

As for the Biarritz, the 15th hole (par 5) at Glen Mills is a downhill shot into the green with the topo going away. The two-tiered green with the swale and lower level on the rear is opposite from the Biarritz, but works for the shot and strategy of this particular hole.

Greens are the face of the portrait and the emphasis on this particular hole – as with most – was to create interest for those attempting to get home in two, and provide a demanding approach for those that laid back on their second. I think this is an appropriate dynamic for a par 5 green.

5. As a former course superintendent, your courses pay special attention to drainage. Talk to us about how design and drainage interact.

Very simple–if a hole does not drain, it does not work. Drainage is the most important aspect of any project. It all starts with knowing where the outfall is, how to get water off the hole–all of which is typically a challenge unless one has a sandy site, which is always the simplest. Proper drainage, both surface and sub-surface, impacts design, construction and maintenance, which ultimately has a hand in determining playability.

6. As consulting architect at Grandfather Golf and Country Club, you are overseeing some work. What is your vision for improving Grandfather?

Grandfather G&CC is a noted layout by Ellis Maples completed in the late 60’s in the mountains of western North Carolina.

The layout has been altered slightly over the years along with mother nature taking its toll, with tree encroachment and deteriorating drainage. Our firm has generated a plan to return GGCC to loftier perches by improving the infrastructure (drainage and irrigation), followed by re-working the green complexes and fairway bunkers. The constraints to complete this work are a challenge, as the golf course will not close during the summer season. All the improvements will be completed during the shoulder seasons in the late fall and early spring.

7. What features have been lost that need to be restored? Conversely, what new features could be added that would enhance play?

The club is blessed with copies of Maples’ original drawings, which allow for a good evaluation of the course’s evolution. The green complexes and bunkers seem to have been altered a number of times with a departure from the original design, which seem to involve more ‘broken’ lines and less of the smooth curves seen today. Most notably, the greens have been elevated several feet above their original heights, which limit the variety of shots possible around the greens. Further, most of the bunkers seemed to have been watered down in their shape and size, which leads to a further loss of character and strategic value.

By lowering the greens and re-establishing the bunkers within the context of today’s play, I think you can add tremendously to the variety of approach and short game play, which gives every course a richer texture.

Maples routed the dogleg right sixteenth along the creek but the passage of time and tree growth rendered the creek meaningless. Work carried out over the winter of 2015 has seen the return of this feature.

8. You have noted that Grandfather’s bunkering is out of scale with the course. Please expound on that observation.

The original bunkering strategy was predicated on a 700-750 foot angle turn, which is mostly obsolete today as our angle turns (landing area) are out at 850 and sometimes 900-feet, for bunkering strategy. Combined with the evolution described above, I don’t think the current bunkers quite live up to the standard that the rest of the course sets, at least in terms of lending a unique character to the layout.

9. What three non-Weed courses do you most admire for their bunkering schemes? And why?

I think first of St Andrews -Old, as the weather conditions dictate how the course plays and the mostly natural bunkers are ever-changing from a strategic position. The contours and wind make the bunkers come into play differently each day; their influence is constantly changing. For such a noted and aged layout, the bunkering has always confounded every caliber of player. I think we all strive to build holes as slippery as those on the Old Course.

Secondly, Harbour Town, as its design ushered in a new, modern era of design as the bunkers and their angles stretched out to challenge play from every tee. The combination of large expanses of sand and the small pot bunkers brought about a new level of strategic design that really could impact a wide range of players in an equitable fashion.

Lastly, I would offer Pine Valley. I think Pine Valley is the best example of how bunkers can have a dramatically important aesthetic impact on a property. Sometimes – but not always – site conditions allow for a unique style of bunkers that contribute to a layout’s overall theme, tying together the various elements into a completely integrated landscape. Those are often the most identifiable courses with the strongest sense of place.

10. You built Mito Kourakuen Country Club in Japan. What challenges did you face in working in Japan?

With this particular site – and most in Japan – the difficulty is typically the severity of the ground. All property deemed as farmland cannot be used for golf, which meant at Mito we were left with significant topo. Secondly, many parcels of land had to be assembled, creating an arduous process of land acquisition for the owners. The topo was very challenging and difficult, often making a walkthrough of the routing nearly impossible. The costs associated with the construction on such challenging topo were almost incomprehensible, particularly at this site. I think at one point during construction, there were over 60 excavators on the job site!

The above photograph of Mito indicates some of the topographic challenges that needed to be overcome in both the routing and construction process.

11. Course rankings always create a lot of discussion on GolfClubAtlas. As an architect, how do you view the various magazine rankings?

I think there was a day when the rankings held more status. Today, it seems everyone has a ratings list with different metrics. Top ranked courses today consist of, Best of; Private, Public, Resort, Development, Modern, Golden Era, etcc… It seems today, the ranking process has lost its luster along with some credibility. The criteria used for ranking appears sound enough, I simply question who is judging and the merits of their knowledge and depth of understanding design elements.

12. I couldn’t agree more! Let’s move on and talk about one of your most noted original designs, The Olde Farm outside of Bristol, Virginia. It features wide fairways and significant green contours. How do those features play into good design?

In the case of the Olde Farm, the site was large and open, void of trees with some gentle, rolling contours for the most part. The site begged for large features (i.e. fairways and greens). It has to do with the scale of the site. Wider is always preferred…

13. Despite a couple of uphill green to tee transitions, The Olde Farm is an enjoyable walk. How important is walkability in your designs and what would you sacrifice to ensure a walkable routing?

The routing at the Olde Farm is north-south oriented, and flowed well with the natural ridges and contours of the site. Anytime you have a core-routed layout, it should be a walkable and enjoyable course. A core-routed course is the purest form of golf. Anytime a development golf course dictates the routing, the integrity of the layout will be compromised, with few exceptions.

This particular property had a previous routing plan oriented east-west. The owner, Jim McGlothlin asked if I cared to see this dated routing plan upon my first site-visit and I simply declined as once I walked the site, it was obvious the routing had to be north-south, as any other routing would have been rubbish.

Larry Lambrecht’s photograph of the tenth hole at Olde Farm captures the bucolic charms of a round here.

What I would sacrifice for a walkable course? It’s hard to say exactly, I think most designers have an internal barometer that tells us when things are getting too ‘forced’. Nevertheless, I think the Olde Farm is an indication of how to maintain walkability while mitigating topo. Most major topo changes are managed on par 3’s (i.e. # 15) or between holes, (i.e. the walk from 2 green to 3 tee at the Olde Farm). The key is not to design an awkward playing hole due to a routing that is forced, if possible.

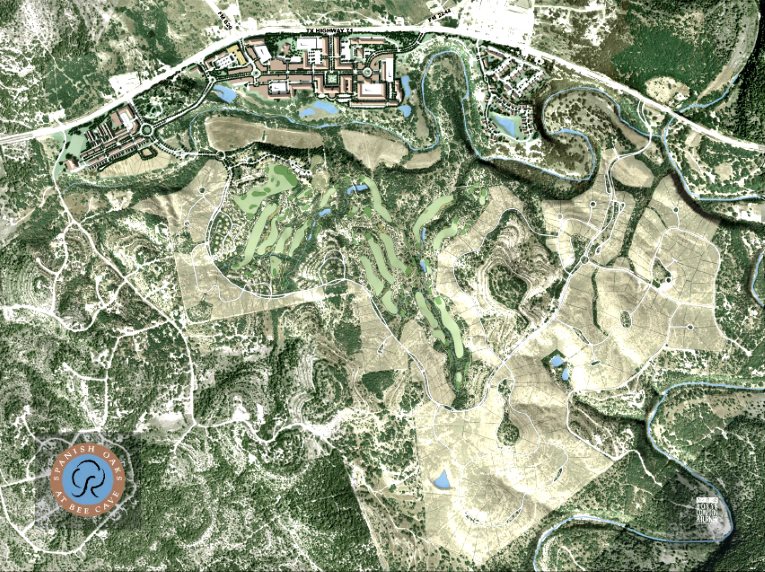

14. Talk about the benefits of your land plan at Spanish Oaks. How did the fact that the golf is core assist you in coming up with the best routing, and therefore best course?

Most sites have some level of restrictions (i.e. environmental, wetland, etc.) and Spanish Oaks outside of Austin, Texas was no exception. We were blessed with a knowledgeable owner with a keen sense of the game, which is often a good situation. The owner, Daniel Porter quickly realized and bought in with our intent to keep the course routing low and the housing above the golf course as he never intended to sacrifice the quality of the layout. With a core-routed course, Mr. Porter recognized that he could have a unique golf course and with generous setback boundaries, have housing that would not impede on the golf course, but instead offer lot values with long vistas and views of the native hill-country terrain. The resulting development and golf course may be the most environmentally sensitive project in Texas. It became something of an environmental rehabilitation project, as we re-established large swaths of the native Hill Country grasslands via the construction of the course.

15. Given the paucity of new course construction in the United States at the moment, architects are forced to focus on renovation work. Your renovation of Deltona Club was quite dramatic. Please share with us some before and after photographs and what you were trying to accomplish. The visuals are obviously dramatic, but how did the changes affect the maintenance budget?

This project would never have occurred had it not been for our design team convincing the owner, Wallace Cahoon, of a ‘Repurposing’ opportunity. Altering the layout and carving out a 17-acre development enclave creating a partial land-use conversion within the property allowed the financial stimulus to upgrade a faltering club.

The site was sandy, with rolling terrain in central Florida, just north of Orlando. The old golf course was a typical development layout with wall-to-wall turf and a substantial amount of turf-grass to maintain. Our ‘Repurposing’ renovation consisted of exposing much of the native sand, creating an eye-popping layout that offered interest and aesthetics not previously seen in this area. The result was less, overall maintained turf area, utilization of a lower quality pasture grass (bahiagrass) in out of play areas with a reduced irrigation system utilizing less water on the course.

16. Tell us the story of the renovation at Timuquana Country Club. This 1923 Ross has a distinguished history.

I was contacted in 1995 by this private club which sits along the banks of the St. Johns River outside of Jacksonville, Florida. The club had a number of issues associated with drainage and the use of multiple wells on site for their usage. Once we had the assignment and upon a site inspection, we identified a number of drainage outfalls that had been slow draining for decades surrounding the core routed layout. We identified how much freeboard really existed and the drainage of the project became workable. Abandoning the ground water wells was more challenging. We were able to successfully negotiate a win-win with the adjacent Navy base to cap the golf course wells and take the Navy base effluent and eliminate their disposal of effluent into the St. Johns. This was a significant benefit for both entities, not to mention a novel agreement between a government entity and private club.

The club had gone through three known renovations, starting with Robert Trent Jones back in the 40’s or early 50’s, culminating in a layout that had little to none of its original Ross features.

Upon reopening, the club invited the USGA Executive Director down to inspect and play the golf course for future USGA events, along with other Ross aficionados that lauded the club for its preservation of the Ross layout (?!)…Soon thereafter, the club was awarded a USGA Senior Amateur event, which I think is a testament to the spirit of the place.

17. You have built four TPC courses, yet none in 19 years. Is that a concept whose time has come and gone?

To the contrary, I think the concept was perhaps ahead of its time and might be more relevant today than ever before. Initially, the TOUR partnered with developers that were planning to build courses as part of a real estate venture. In this agreement, the course would be branded a ‘TPC’ with the notion that it would hold a TOUR event. In return, the developer agreed to construct the course with specific tournament hosting infrastructure in mind: thicker and wider cart paths, tent staging areas, spectator areas, hospitality, tournament wiring, etc.

Not least of these considerations was the course itself, which would be built specifically to test the best players. I often think how different the landscape might look today if this concept became fully realized, and all the TOUR’s events were held solely on a circuit of 30 or so TPC courses, all designed specifically for the world’s best players. This is not dissimilar to the way NASCAR travels to the same tracks. Maybe clubs wouldn’t be in such an ‘arms race’ to constantly modify courses in an effort to stay relevant to what is a very small percentage of players. Maybe by segregating the world’s best players to a series of courses designed for their abilities, we would be acknowledging the obvious: they really are playing a different game than the rest of us.

18. Please delve into the statement you made in Life and Leisure regarding the 15th hole at TPC River Highlands that “half-par holes are the best holes in golf.”

I would guess that this is a point that is well understood by the GCA crowd. Par is an arbitrary and meaningless number.

Too often, golfers allow par to dictate how they play a hole….e.g. oh this is a par-4, I have to reach the green in two shots. This narrow thinking is incredibly damaging to golf. Part of the game’s charm lies in the strategic calculations a course should compel us to make. Take those away, and I think you’ve damaged the foundation of golf’s interest.

Half-par holes change that dynamic. They don’t fit neatly into a box, so the golfer is forced to do some thinking on their own about how they will play the hole. They can’t simply rely on ‘par’ to do their thinking for them.

19. Within your own body of work, which are three favorite half-par holes and why?

The 15th at River Highlands is one. It still presents the same dynamic decision making process on the tee to TOUR players as it did when it first debuted over 20 years ago.

This view from behind the fifteenth green highlights the bunkers short left and long right off the tee, as well as the pond which is in play for any pulled tee ball. Additionally, the domed green has a way of effectively shedding golf balls.

The 2nd hole at the Olde Farm is par-4 which is stretched out to over 500 yards today is a par 4.5 and early enough in the round for players to decide whether to carry the creek in front of the green or make a go of it. Having a forced carry approach so soon in the round, especially after the benign opening par-5, is an interesting crossroads for the golfer to face.

Finally, I’ll steal a line from Pete: my next favorite is whatever one I get to build next! For anyone that’s involved in a creative profession, I think the main thrill is in the process of creation…once the ‘thing’ is built, it’s hard to evaluate it in the same objective manner as anyone else. You just want to get on to the next one!

20. You were the first recipient of the David Hueber Sustainable Golf Community Sustainability Award. Please share with us your views on sustainability and golf. Where do clubs often – though accidentally – misstep in this regard?

We have a somewhat trite saying around our office: “The first step to sustainability is profitability.” The essence of that notion is that any operating strategy – for any course – needs to be financially self-sufficient in order to persist for the long term.

This particular award dealt specifically with our work on “Repurposing” projects like Deltona. So, my answer to your question is that I think not enough clubs – especially those in the 25-45 year old range – look objectively enough at the land uses of their real estate when charting their futures. Many of these clubs are in desperate need of significant capital upgrades and their properties often have ideal locations. Yet they are very resistant to incorporating additional land uses into the property.

Carving out 10-20 acres of valuable infill development land from a golf course can be the engine to fund comprehensive capital improvements and vault a facility ahead of the competition for the long term. The value of these parcels can approach eight figures, which is enough to rebuild the entire course from top to bottom & be positioned for the next 20 years with no additional debt. Plus, the resultant golf courses are often more compact and intimate, exhibit more interesting strategy and more modest lengths, and are more efficient to maintain. You can’t be more sustainable than that!

The End