Feature Interview

with

Andy Staples

March 2018

Tell us about your background and how you became a golf architect.

I’m similar to a lot of guys in our business – became obsessed with the game at a very early age, and I liked to build stuff. I also loved to draw. I’m from Wisconsin, and in the summer, my family vacationed to a small lake house in central Wisconsin; Lake Camelot in Rome as a matter of fact. It was a pure sand beach, perfect for practicing my sand shots. These practice shots turned to playing to one point on a little slope, which then turned into a flat rudimentary sand green, and 9 small areas used as tees. My course was 9 short holes of less than 25 yards, which could be played twice. I worked on my course every weekend, and one day my dad asked me if I knew people design courses for a living. I was around 12 at the time, and was blown away. I knew at that moment what I wanted to do with my life.

I studied Landscape Architecture at the University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, where I had hopes of walking on to their golf team (nay!). I also traveled to Copenhagen, Denmark to study Urban Planning and Design. An early mentor, Tulsa-based course designer Jerry Slack, gave me the direction that I should go work in construction to learn the nuts and bolts of how a course was built, so I started with Wadsworth in Green Bay, WI and in Arlington, TX. After working in construction for a while, Jerry hired me as a draftsman, which got me “into the business.”

I then took a position for Bob Graves and Damian Pascuzzo when the industry was flying in 1997, and got to travel the world working on their projects. In 2003, I left to start the Golf Resource Group with two partners, focusing on the management side of the industry. Our first contract was for Thanksgiving Point in Utah, providing contracted maintenance services on an annual basis. Yes, I actually got on to a mower! They even let me hand mow greens. I have been on my own ever since.

Who were your major influences?

My largest influence is my ol’ man, Jim Staples. He was a bit of an entrepreneur, and a lifelong 15 handicap. He taught me that it was ok to take a few risks in business, and how to hit a putter from 50 yards off the green.

From a design perspective, the one influence that is seared into my brain is Langford & Morreau. I learned to play golf at West Bend Country Club in WI; an original L&M design. I recall as a complete beginner what is was like to navigate those deep design features. I remember vividly thinking that golf was a hard game, and that I needed to practice a lot to get better. I think this aspect of golf is why I became infatuated with the game.

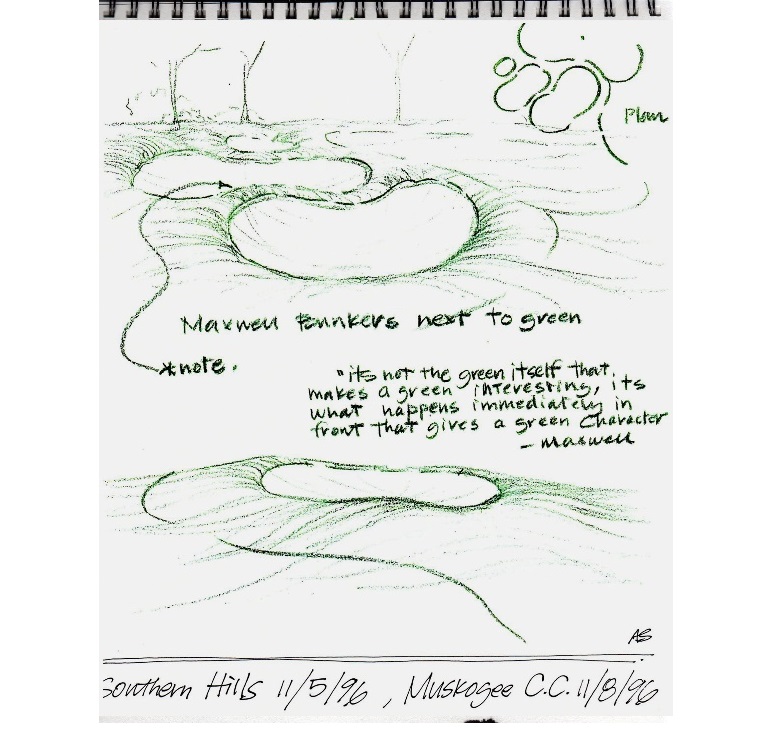

I lived in Tulsa when I worked for Jerry, so I got to know Perry Maxwell during this time, which was great because Southern Hills and some of his others were near where I lived. I admire how he was able to make a major impact in our business, all basically during the depression.

You emphasize “green sustainability.” Tell us how that is implemented and how it affects the creative process.

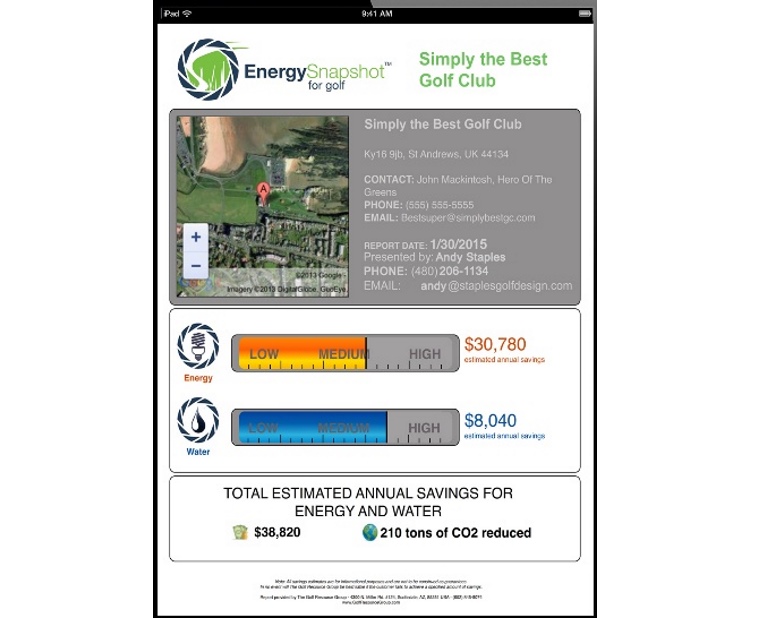

As a little background, here’s a short story on how this part of the business started to make sense to me: I was living in Northern California at a time in which the state deregulated the power business. I recall sitting in my living room on a Saturday afternoon, watching TV, and the power to the entire house just switched off, totally dead. They called them rolling blackouts. That was how the utility was handling their business – they would shut the power off to their customers because it was too expensive to deliver it at that moment. It became clear to me that the resources we took for granted, and those we thought would be available forever, and for a cheap price, may become less available in the future.

For me, the creative process related to sustainability is about checks and balances. I feel my background in areas outside the design side of the business have enabled me to view the golf course more as an entire system. I look for ways to minimize the high use or expensive costs on a specific area of the course, and place the effort and budget into another more visible area. Irrigation management is the best example. Bunker design is another good example, as is overall fairway acreage verse individual hole width. Much of my process begins with being aware of the sensitivities in the areas I work. I’ll then plan for how to responsibly address their resources and costs, and then finally make design decisions that best fits the type of golf course we want to create.

I try to never talk in terms of “saving,” but in terms of reallocating the funds. My clients know that I am always thinking about how to reduce our overall footprint, and that my design will ultimately reflect a sustainable philosophy. I’ve stepped out on a few limbs, especially in the area of irrigation, which I think will ultimately make the industry better stewards of our land and resources. In most cases, this process is invisible and running in the background, as clients hire me to create great golf courses.

Please provide one such example of reallocating funds from irrigation to another area.

One area I’ve spent a bunch of time on is irrigation sprinkler layout, and the total number of sprinklers needed to create great conditions for golf. The less sprinklers you install, the less you have to maintain, and the less it costs to install. I’ve listened intently to guys like Don Mahaffey, Dale Winchester, Sean Tully, and Josh Heptig, on how what it takes to develop healthy turf, that looks and plays the way we want it to.

Another area is energy efficiency. I’ve been able to reduce the power bills on a lot of golf courses by working with the superintendent on improved programming of their irrigation cycles.

In all cases, I try to communicate to the decision makers that these “savings” be allocated to more labor, or put a little more towards details around the bunkers or greens.

Several GCAers have been blown away by your work at Meadowbrook in Detroit. Tell us how you got involved there.

So, I was placed on a list of 15 architects in which the Club was intending to interview; guys from across the country, both large names and small. It’s actually a bit of a funny story, as the email from the General Manager requesting my interest in the project never went to my main email account; it went to my ‘info’ account. Right at this time, our 3rd son was born, which took me away from my regular routine. When I finally saw the email (which was a day before my letter of intent was due), I frantically called Joe Marini, the GM, and caught him in the car on his way home from the Club. We ended up speaking for over 2 hours. I guess he was in his garage for most of the call, with the car running, with his wife wondering what the heck was going on. We still laugh about this today. It turned out to be an uncanny connection, and a foreshadowing of things to come. I have yet to have a more personal connection with an entire membership as I do with Meadowbrook. It’s been very special.

How it was it decided to emphasize Park even though he was responsible for a minority of the original holes?

Meadowbrook has always considered themselves a Willie Park Jr. design, even though Park only designed 6 original holes (only 5 original greens were still intact). This lineage was something the Club leadership prided itself on. Interestingly, when going through the design process, many of the rank and file members didn’t really know what it meant to be a “Park design.” They knew there were a few greens that looked and played a bit differently than the others, but for the most part, they were somewhat indifferent about it.

When we got into the weeds regarding the direction of the plan, I submitted to the committee, then ultimately to the membership, that taking this historic design lineage, and moving the needle up in terms of making it something unique, was the best route to take. I discussed what was special about their current Park features, and examples that I felt would make them better.

As part of this focus, I presented that I would do my research, both in this country, and in England, and bring back to Northville, a theme that would set them apart. They loved it. So, I would say the Club gave me the initial push in that direction, but it was the overall vision and excitement for what Meadowbrook could be that sealed the deal.

Were you a Willie Park aficionado before doing overseas research at Sunningdale and Huntercombe?

I wasn’t. I’d always put Park in the same camp as William Watson, Tom Bendelow, or Charles Banks; someone that doesn’t get much pub in terms his style and certainly not a guy I encountered very often. I read The Art of Putting, and gained insight around how he viewed the game as a player, but his work wasn’t something I spent much time on. We visited many of his courses, including what I feel is one of his best in Battle Creek, MI, and did our best to clue in on what made-up his design style and philosophy. But, to be honest, my initial feelings of his work were pretty neutral. Man did that change though when we got to Sunningdale, and then ultimately to Huntercombe. His work in England, especially at Huntercombe, really resonated with me as something different from what I’d seen in the US, and that gave us priceless insight into his philosophy.

I am with you on Huntercombe – what a design! What impresses you most about his designs? For instance, Huntercombe was built over 115 years ago. How does it stack up to the modern game?

The first aspect of his courses that are notable are his greens. He seemed to place much of his focus on the placement of the green in a way that allowed the ball to be run up into, and placing a premium on judging the correct distance. It’s clear his philosophy was meant for firm and dry fairways, and that he expected the ball to run out when it landed near the green surface. None the less, his greens are his most distinguishable feature. Typically they’re severely sloped, usually from back to front, falling off on both sides, with a harsh penalty over the green, most likely a sand bunker.

The other aspect I appreciate, and this is certainly evident at Huntercombe and Sunningdale, is his rudimentary use of land formations that serve as hazards, as well as some other practical purpose, namely the use of ditches, or “pots” as lows for drainage, or which helped the maintenance in some way.

At Huntercombe, they call their grass bunkers “Willie Park Pots.” I was reminded of features I’ve seen at Oakmont or Garden City. I’m by no means a Park Jr. expert, but I do understand him better after seeing a bunch of his work, and hope that some of those features give a sense of his philosophy at Meadowbrook during the turn of the 20th Century.

There are some extremely bold, almost severe features at Meadowbrook. Some are original to you and others to Park. How do you decide when it is best to augment a Golden Age design?

First, in terms of the bold nature of some of the features we built, I feel many of these are very typical of turn of the century design, and we wanted to give Meadowbrook the sense that it may have been built in a different era. But, this is where I must give credit to the Club; guys like Joe Marini, Tom Donohoe (the president at the time), committee member Jim Dales, and greens chair Tom Doyle, challenged me to pay homage to Park, and build something cool.

In some respects, I actually backed off in a few areas. Our design shaper, Scott Clem, and I worked together to find ways to balance the design, with the everyday maintenance. Mike Edgerton, the immediate past superintendent, and then the new super, Jared Milner, were also supportive and really wanted to not handcuff us. So, client support is always key. Having the support from your superintendent is also a must.

In terms of knowing when to augment a Golden Age design, it’s in the client’s best interest to look for ways to make their course better. At Meadowbrook, I tried hard to understand why the current routing was the way it was (supposedly Collis & Daray implemented Park’s 18-hole routing when it expanded from 6 holes to 18), but I had a really hard time feeling good about the routing in its current state. It didn’t have great flow, and was a bit disjointed. Old #4 was not a good golf hole, as it was very difficult for the average player. Hole 14 had the ability to use much more land to the west, but was a narrow, blind, drive and pitch hole. The transition for holes 5, 6 and 7 were unsafe, and caused awkward walks from the green to the next tees.

Just because something is old, doesn’t make it good. So, I think it is key to understand the original intent, understand if restoring it is even possible or reasonable, then make recommendations for how they can improve. If we had record of Meadowbrook being all Willie Park Jr., and we knew his intentions of the property, I think we would have handled the site much differently than the way we did.

What should be the primary goals of a course restoration? How important is the intent of the original designer?

For me, the primary goal of a restoration should be to re-create exactly what the original architect built, and not what we think he or she built. Understanding this difference is important. I love it when you can see evidence of what the original designer built on other courses, and use that as inspiration for what do on another course. This is essentially what we did at Meadowbrook. One of the most exciting things to come out of the restoration movement is he ability to push the envelope in the recreation of forms and features that are not only strategic, and fun to play, but continue to meet the goal in the overall maintenance budget.

With regards to understanding the original architect’s intent, I think it’s absolutely necessary and I believe this to be true even if the course is of modern vintage. I know how hard it is to balance all the constraints of a project, especially these days, and the impact many of these constraints have on the creative aspects of the business, but in the end, if we’re talking about a restoration, the design’s integrity must remain intact.

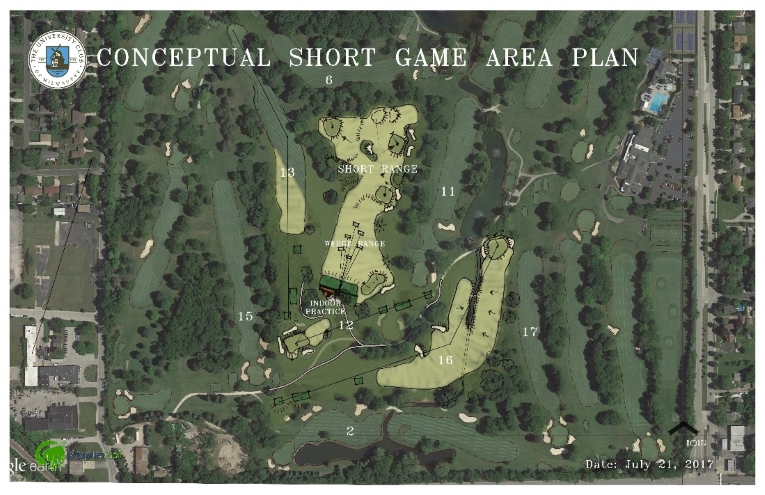

Currently, I’m working with the University Club of Milwaukee (formerly Tripoli Country Club), a 1921 Tom Bendelow design, of which we’re bringing back much of his original intent based on photos of the course. Interestingly, he built over 100 bunkers (they currently have 52), so we’re going through an exercise of understanding where he built his bunkers, and what their purpose was to get a sense of what to bring back. There is no way we can afford to maintain 105 bunkers, but we’re asking which ones are most indicative of his intent.

For example; Bendelow built long, winding bunkers behind a number of his greens at Tripoli. These have been eliminated over the years due to maintenance and playability. Now, I’m one for a hidden bunker behind greens, especially if Tom himself actually built them, but I can’t defend multiple bunkers that only the average player gets into. So we’re analyzing each green individually to understand the contours in order to determine how important some of these bunkers are, and how Bendelow indented the back pins to be defended.

With all that said, if you don’t have good ground photos of what was actually built, or a good aerial survey of a specific period of time, or perhaps even notes of the designer’s thoughts throughout the creation of the course, a true restoration is not impossible, and interpretations must be made.

Please discuss two such ‘interpretative’ features. Were they readily accepted by the membership?

The first has to be the new 3rd green, a fairly specific interpretation of the 4th at Huntercombe. It’s an “L” shape flipped in reverse with the back-right section lower than the rest of the green by almost four feet, which creates a bowl effect. It also has a slight spine running from back to front that subtly splits the green; one section draining left and the other right, down to the bowl. When we first shaped this green, we took some serious H-E-double hockey stick. The term Mickey Mouse was used quite often.

The team during final shaping of the 3rd green at Meadowbrook, a mirror image homage to the 4th at Huntercombe.

We shaped it, and let it sit there for a few months. It actually sat rough shaped over the winter. Part of the reason for this was so Scott and me could ruminate on the exact slopes, and strategy, but the other reason was for it to become more understood by the members. There was a moment this green could have been changed and flattened. But again, it was the Club that stood next to me and Scott- the ones who got to play it in England, that said this is reeeeeeeeaaaaaally close to a green that Park himself built on his own course, and this would be an incredible homage to Willie, and to Huntercombe. And, since the idea for the green actually came from Park on one of his own courses, and not Andy Staples, it became more authentic or “reasonable.”

The questions started to fade, and appreciation began to set in. It wasn’t until after we opened, and started firing shots down to the lower bowl that the real affinity for the green began. It’s a short approach, so most players should have a bit of control on their approach shot. It’s an absolute blast to send a shot over the edge, and walk up to see where it ended up. It’s the feature that everyone looks forward to playing, and is certainly the most talked about. Thanks to Huntercombe for the inspiration! (For whatever it’s worth, here’s a more thorough run-down of the hole by Andrew Bailey for those who may be interested; (http://www.friedegg.co/golf-courses/meadowbrook-3rd-hole)

Another example is the tiny 9th green. It’s a short drive and pitch hole, that is set up from the tee, and a decision as to the length of approach you want into the green. The better player can take a run driving the green, while most other players need to lay up to their preferred yardage. It’s the smallest green on the course, falls off on all sides, and is defended by three bunkers. It does have a small back stop behind the surface, so an approach from the extreme left side gives a fair bit of margin of error in terms of distance control, but not much. This hole has evoked the most wide-ranging opinions of any of the holes on the course.

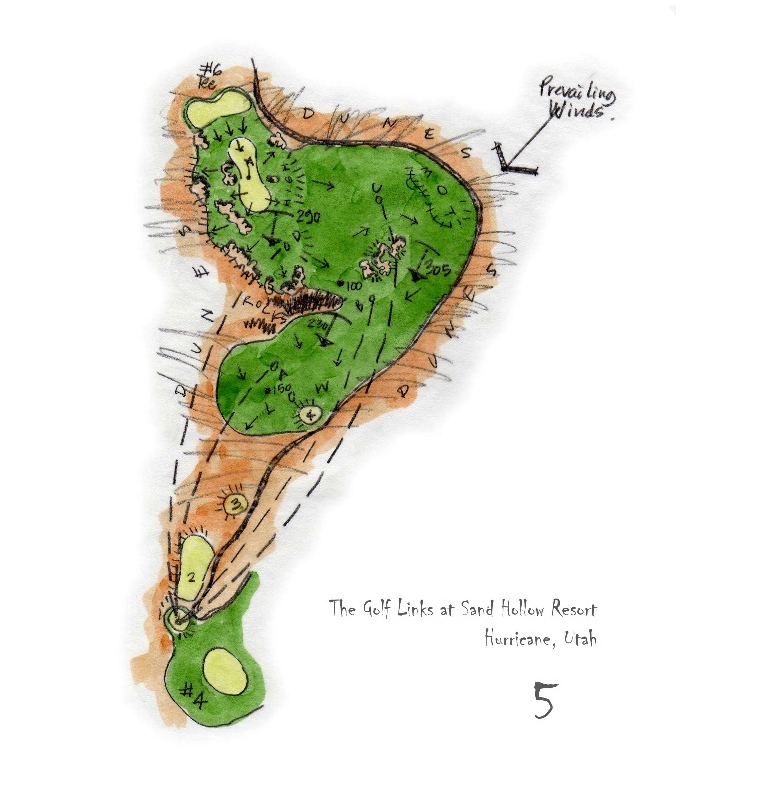

Most members are still figuring out how they should play it. I’ve seen really good players make all kinds of big numbers, by taking wrong angles. This green design was mostly driven by me and Scott with very little Park, however the 17th green at Huntercombe does come to mind. If I were to have my own personal template, this would be it. A short hole with a huge fairway that dares you to go directly at the pin. If you have the shot, you take a swipe at the small, angled green. But, if you lay up, or play safely, your approach is tricky. I guess it’s a bit of an adaptation of the 10th at Riviera, or even the 4th at Woking in England. I built a hole like this at Rockwind in NM. I almost built this hole at Sand Hollow (see hole #5 sketch below), but it was eliminated by the owner for housing. C’est la vie.

That’s really neat. One last feature spring to mind?

Here’s an interesting side story: the 17th hole is a reachable par 5. In order to give the approach to the green more interest and strategy, we shaped the entire complex à la a Biarritz, with a strong swale separating the approach and the putting green, then protecting the front and sides with bunkers. One day, in the pub, a member comes to me and asks specifically about the 17th green, wondering what I was thinking. The member, someone I knew to not be overly interested in golf architecture, was intrigued, and after having listened to my presentations, was acutely aware that this green was something he’d never seen before, and was inclined to think this was something he needed to know about. I explained to him the idea behind a Biarritz, and told him to search the internet to find out which courses around the country have this type of feature.

A few days later, he saw me walking around the club, and ran over to me as excited as I’ve ever seen a member. He told me he now knew exactly what I was describing, and was amazed at the types of clubs that had a Biarritz feature. This is what I feel we as golf course architects are meant to do: educate our clients about what makes good architecture, and why the ground game means so much to the enjoyment of playing a course. It’s clear that players can have more fun if they open their minds to design intention, and that is something I love helping them discover.

What are some examples of holes that we would all recognize on television that you wish you could claim was ‘Staples originals’? What do you admire so much about them?

I love the 17th at the TPC Scottsdale. The back portion of that green reminds me a bit of the green on the 6th at Chicago Golf Club. It’s a great risk-reward short par 4, that challenges about every type of approach. I also really like how it makes you want to go for the green.

Also, I love the 10th at Riviera for all the reasons I like to use this type of short hole in my routings.

I use the 7th at Pebble as proof that a short par 3 can be really good, and fit nicely into a routing. The short par 3 seemed to be a hole that for years, no one was building. That’s a shame.

You refer often to Community Links and environmental sustainability. How do they tie together?

I’m a firm believer that a community’s leadership has a responsibility to plan for a sustainable future. That means being a good steward of land and resources, and requires those at the top, often municipal office holders, to be paying attention. Also, an aspect of sustainability that isn’t spoken about much because it’s not well understood, is the social aspects of a golf course. Community Links is a paradigm shift for how community leaders should view their golf course, which uses the game of golf as a nexus for healthy living, community pride, and raising our youth. Further, “CL” emphasizes uses for both golfers *and* non-golfers, which is vitally important today when getting support for investment into failing facilities.

Anyone that’s been around the game for a while knows all the benefits of golf, and my aim is to meld these benefits with responsible environmental stewardship, in order to further the game to as many people as possible. It’s one way I can leave golf better than I found it, which is something I strive for always.

Rockwind Community Links focused on integrating non-golf uses, such as a comprehensive trail system, to bring more people to the golf course.

The range at Rockwind was designed to host a variety of programs including beginner programs for kids.

We look forward to visiting your most heralded original design – Sand Hollow in Utah. Tell us about that project and what design features we should look for.

Sand Hollow holds a really special place in my heart, as it was my first design contract on my own. I was introduced to the owner, Dave Wilkey, in 2004, and helped him get the entire development approved through the State, the City of Hurricane, and the Bureau of Land Management (BLM). It is still the most natural site for a golf course I’ve had a chance to work with; huge red sand dunes, set atop incredible sand stone cliffs, next to the Virgin River (a major tributary of the Colorado River). Ultimately, when it came time to build the course, I was teamed with John Fought to bring it across the finish line. I lived in Utah during the entire build, and handled the day to day management of the development. Interestingly, Forrest Fezler and many guys from Mike Stranz’s team, were the builders of the course.

You need to look for how the course routing takes you through a journey of the property, and gives you a real sense of the land as if you were to take a 4 wheeler, or a hike. The site is dominated by two huge rock outcroppings, and a spectacular rim of rock formations normally found in national parks.

Also, make sure to get over to the “Links” Course; a 9 hole course intended to be a wide-open, with multiple angels of play, for a reduced rate for the local residents. It can be played in different variations, and from different sets of tees. I’ve been told by some, that they like these nine holes better than the Championship course, and, I tend to agree!

Was it a hard course to route?

In short; no, because many of the dramatic features of the site drove the overall layout.

The longer answer requires imagining various parcels of BLM land interacting with the owner’s property; two of which were “island parcels” within the owner’s property itself. The entire site was amazing, but it was on the BLM land where some of the exciting sand dune features existed. From the outset of the routing process, we knew that BLM had serious concerns about how this development would affect the preservation of their land, but we ultimately worked out an agreement that had the golf course in charge of preserving it for them.

Once we had everyone’s support, routing the course essentially became an exercise in maximizing use of the BLM land. The whole project turned out to be a real win-win-win; we developed some amazing natural golf, more of the owner’s land could be used to develop the resort now that the golf course was given access to BLM land, and BLM sites were preserved and protected. Overall, we still worked out over 20 options ranging from 36 holes, to 18, then settling on 27.

The other major challenging aspect of the routing was the rock ledge on holes 11 through 15. This was the only portion of the property void on any sand, but obviously was an incredible asset for the course, and adds tremendously to the golfer’s experience. Interestingly, John and I tried to convince the owners to not put golf on this area, as it just seemed overly expensive, especially when we had some other impressive sand dunes on the top of a nearby ridge to work with. We would still have the views, but not have to excavate the rock, and cap the area with 3 feet of sand. Ultimately, it was Dave Wilkey that said there was no way we weren’t going to have golf holes on the edge of the cliff, and committed to paying the added expense to build the holes. Without a doubt, these holes are the most dramatic on the property (if not in the entire state!), and is what drives many to come experience the course.

Given its setting, was scale easy to come by?

We built the entire course out of the native sands, ala Sand Hills or Ballyneal, so the most difficult aspect of scale was determining how big we wanted to go? Once the ground was exposed, we really only shaped the greens, tees and bunkers, and hardly touched any of the fairways (with the exception of the holes 11-15 on the Championship Course). The wind blows pretty hard there (the name of the town where Sand Hollow sits is Hurricane), and we all knew we needed some extra width to account for the different wind directions. All the sand for the greens and bunkers was native to that area, so establishing green sizes, and cutting in the features, became an exercise in irrigation spacing, and overall width of play.

The entire course, except the greens, was seeded with dwarf, low mow bluegrass, so we were able to make the fairways as wide as they wanted to maintain. They say working in sand is the ultimate, and after working on Sand Hollow, I can wholeheartedly say that it doesn’t get any better than that.

Design sketches for the Championship Course at Sand Hollow:

Congratulations – I can’t wait to get there. Moving on, you seem experienced in building practice areas. To what do you attribute the recent surge in popularity for multi-purpose practice areas as well as ‘short courses’?

Well, I think that life is just getting busier for all of us. I have three young boys, and travel a fair bit during the week, which means I don’t have the time to play 18 holes on the weekends. Obviously I’m not alone here, and sometimes the best we can do these days is take our kids to play 5 holes, hit balls, or putt on the practice green. This type of societal trend, in my opinion, is what’s driving both private and public facilities to become more flexible in their product offerings.

My own life is indicative of this growing desire to spend less time at the course and I’m able to speak directly to how it will affect my client’s customers’ experience. Right now, I’m involved with 5 clubs either expanding their practice ranges, adding short game areas, providing short courses for juniors, and for three of the clubs, we’re allocating space to house golf simulators. The advancement of virtual and augmented reality in golf is pretty incredible these days, and I foresee a time where a certain segment of golfers search out a simulator instead of going to an actual range or course. I can’t say I agree with it, but I certainly see a day where someone will go play golf, but never actually leave their home.

Concept Plan for the practice facility at the University Club of Milwaukee – new home of the Marquette University golf team

Yuck, golf is an outdoor sport but so be it. Do you view it as your role as golf course architect to help grow the game and/or make it more enjoyable for more golfers?

I’m not sure about all that, but I do know that great architecture gives a golfer the feeling of enthusiasm for the game, making them want to play more. So, in that sense, we golf architects help grow the game. Operators of golf courses, along with the rule makers, will have the best ability to “grow the game,” but overall I don’t see the game as being in desperate need of growth. I would say we should make what we have better, and continue to provide better golf experiences in the markets that can support golf.

I also feel the game is uniquely positioned to capture the portion of our population that is looking for outdoor recreation, healthy activity, and spirited competition. It just needs to be presented in a way that is more accessible and easier for people to get into, with the intention they become a lifelong participant. It’s a game that can be played well into your 80’s, so it will always be there when you need it. We as golf architects just need to keep providing the playing fields that people want to use, provide them in a manner that gives a bit of flexibility in how they’re accessed, and then ensure they are built sustainably, which allow our clients to make good returns on their investments.

Where do you see Staples Design in 10 years? What will have separated it apart from other firms?

Ha – I wish I could answer that with a bit of certainty! All I know is I don’t plan on going anywhere as long as I can continue to be involved with good projects with great people, that ultimately help the game. I look forward to more collaboration within the industry, as I’m convinced that to make it in this business and “separate yourself,” you can’t go it alone. I’m confident that if I just keep being myself, surround myself with good people, I’ll continue to be successful in my niche of creating fun, sustainable, and community focused golf. Golf’s been great to me, and I’m grateful for that every single day.