Feature Interview with Ran Morrissett (RM): How did you first get into the study of golf course architecture?

Andrew Harvie (AH): Growing up, I was fortunate to be exposed to Mike Mezei who played on the Canadian Tour for years. He was an ace player but more importantly, he was a huge golf course/golf architecture fan. He loved to travel far and wide —Bandon Dunes, The Netherlands, Pine Valley—and come back to little ‘ol Lethbridge, Alberta talking about how amazing these places were. So, naturally, I began to Google and learn about them, which is how I first discovered Golf Club Atlas. It wasn’t until my first round at Banff Springs that it clicked that not all golf courses are designed equally, and once you go into that rabbit hole of learning about architecture, you never come out!

Bandon Dunes

RM: What resources most helped stimulate that interest?

AH: Travelling around playing lots of golf courses helped early. As a junior golfer in Alberta, I gained exposure to a lot of the really good golf courses in the province, including Banff Springs, Jasper Park, Wolf Creek, Priddis Greens, Calgary, and more. Even more than the big names, visiting random golf courses and assessing if they were good or not were key to learning about golf architecture: that’s how I stumbled onto Rod Whitman’s holes at Lacombe, Desert Blume, and Waterton.

After that, A Difficult Par was my first golf architecture book, but it wasn’t until picking up The Spirit of Saint Andrews by Alister Mackenzie and The Anatomy of a Golf Course by Tom Doak that it became interesting to read about the subject.

RM: You played competitive golf in your junior days and into college at Wayland Baptist University and Ottawa University, Arizona. Can you identify when the pursuit of score became second to experiencing the architecture?

AH: Well, I still love playing for score and playing matches. I’m a naturally competitive person and so I try to keep my game sharp (relative, of course!), but it wasn’t until playing a few PGA TOUR Canada events around COVID-19 that the focus became more about the architecture than putting up a score.

That shift had been brewing for awhile. During school at Wayland, we played at a variety of courses and one of those was The Rawls Course at Texas Tech, which I always loved and wanted to play there more than the others. Or in Arizona, I would use one of our days off and go see either Apache Stronghold, the Saguaro at We-Ko-Pa or Talking Stick for the sake of experiencing something different/better.

At this point, it became apparent to me that I liked other elements of golf, especially golf course architecture, more so than the scoring/competitive side of the sport.

RM: What was the first “great” golf course you ever played? What struck you about its design relative to what else you had seen?

AH: Banff Springs would be the obvious choice. It’s easy to give credit to its setting or the par 3’s—both of which are excellent—but what really intrigued me was how frequently there were diagonal carries. It felt like a golf course that, if I was striking it well and confident in my start and finish lines, I could take advantage of the aggressive lines on holes like the 5th, 7th, 9th, 12th, 14th, and 18th. Meanwhile, if I wasn’t striking it well, it would make things difficult by having to take the long routes. I felt myself constantly having to truly step up and hit good golf shots, whereas a lot of the other golf courses in the prairies you can get away with bad golf. The bunker schemes in general are so artistic and creative, they seem to pull out the best in one’s game—all while being a blast to play.

The artistic flair of Banff Springs’ bunkers stands out

RM: Obviously, your background, both in terms of residence and focus with Beyond The Contour, is Canadian: what would you like to highlight and emphasize about golf in Canada? What’s the biggest misconception about golf in your home country?

AH: Canadian golf is a peculiar topic to dive into. The biggest misconception of the country is we only have the Thompson Five, the two Colt’s near Toronto, and Cabot—but we have a handful of interesting layouts worth seeing, you just have to look a little harder and potentially drive farther. We have many wonderful layouts that most haven’t heard of. Take Grand-Mere, for example, or Waterton in the west. These are golf courses that would be notable elsewhere, but they suffer from being in rural Canada and far from anything else worth seeing.

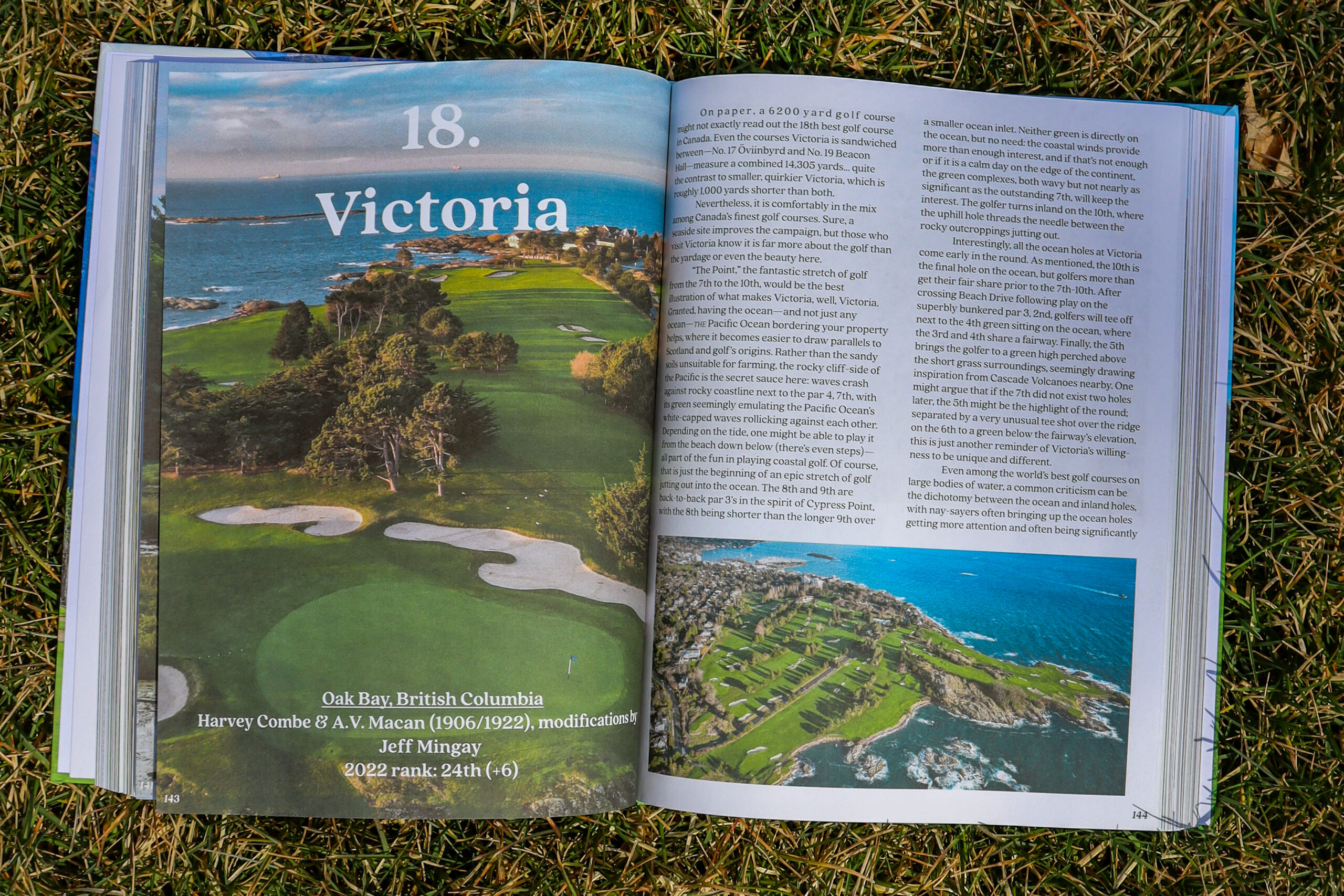

Much of the country has been abused post-Golden Age with poor architecture choices and architects that, to be frank, didn’t care about the previous architect or how notable the previous iteration was. This might sound familiar with what the United States went through, but we’re struggling to come out of it with a restorative movement of our own. There seems to be a bit of progress, but so many unique layouts from architects like Willie Park Jr., Stanley Thompson, A.V. Macan, even Harry Colt and Donald Ross, have been messed with to the point one might not recognize their architectural pedigree. It shouldn’t be surprising that Canada’s ties to Great Britain led to a fruitful Golden Age much like the northeast cities in the United States, but as it stands right now, you wouldn’t know!

RM: Rank your top 10 courses in Canada, in order.

AH: Another thought-provoking question! The Top ~7 in Canada is largely interchangeable in my experience, and you could reasonably argue them all for the best golf course in the country. With that said, here’s my personal list:

- Jasper Park Lodge

- Cabot Cape Breton (Links)

- Cape Breton Highlands Links

- Toronto Golf Club

- St. George’s Golf & Country Club

- Cabot Cape Breton (Cliffs)

- Capilano Golf & Country Club

- Sagebrush Golf Club

- Banff Springs

- Grand-Mere or Hamilton, depending on the day

The first seven courses would feature in any personal world top 100 list of mine.

RM: As you study courses, what are several key components that you break down in your own mind?

AH: I think the two most important aspects of a great golf course are a great routing, and an interesting set of green complexes. To expand, a good routing, to me, is a real sense of place, where it utilizes the best elements of a site. I’m thinking of North Berwick, where it might be a pretty ‘normal’ out-and-back routing on a stick drawing, but does more than enough to showcase the beach, the dunes, the interesting fairways at holes like the 2nd, great green sites at the 9th and so forth. Or Pasatiempo, which has the barranca run through the holes numerous times. Further, a great routing has a true sense of pace to it, as if you were hiking or going on a natural walk. It doesn’t feel disjointed or herky-jerky; instead, it has a nice rhythm to it with a comfortable mix of hole lengths and green-to-tee walks. The complex routings like Muirfield, Jasper Park, or Shinnecock’s triangles are a bonus obviously, but a routing need not be complex to be great: if it has a sense of place with a good flow and utilizes the natural features well, that is more than enough.

Additionally, great greens are the other primary difference maker. That includes not only interesting internal contours, but interesting and unique surroundings. Great green complexes create the “wow” memorability factor for a first visit and are the underpinning to wanting to play a course again—and again.

RM: What is a design element that you think is particularly underrated, one where you place more importance than most?

AH: I love a good bunker-less hole. To me, it’s the sign of not only a good piece of land, but a routing that takes advantage of said property. In the case of most famous architects throughout history, they obviously ~could use bunkers if they wanted, but the restraint to do so—and for the product to turn out so well—is admirable in my eyes, and can often be the difference between two courses if I’m debating which is better. It is not a deal-breaker obviously (there are more great golf courses without bunker-less holes than great ones with) but I appreciate the courage to risk being underwhelming and instead pulling off sophistication.

- The 7th at Inverness Club, a superb bunker-less long 4

- Royal Dornoch’s famed bunker-less 14th

RM: Sister question, what design element do you think is overrated?

AH: Aiming or aesthetic bunkers! A good top-shot bunker or a bunker into the hillside to help steer a blind tee shot is cool, but modern architecture has begun to get a bit loud for me and that’s largely due to frivolous bunkering, sometimes bunkers way in the distance to help define the playing corridors, or bunkers easily carry-able from the tee and hiding ample fairway. There are great examples of aiming or bunkers solely for the purpose of aesthetics, but if I were to guess in the coming years or decades, we’ll see a push for a more restrained style of architecture.

RM: What dozen or so books on architecture make up the nucleus of your golf library?

AH: The Evolution of Golf Course Design by Keith Cutten, The Anatomy of a Golf Course by Tom Doak, The Spirit of Saint Andrews by Alister Mackenzie, Getting to 18 by Tom Doak, The Mackenzie Reader by Joshua Pettit, Lost Links by Daniel Wexler, The Links by Robert Hunter, Colt & Alison in North America by Anthony Gholz Jr., In Every Genius There’s a Little Madness by Ian Andrew, and the Evangelist of Golf by George Batho are all great resources to learn about architecture and architects at a macro level.

Books like Catalogue 18 or The Nature of the Game by Mike Keiser and Stephen Goodwin are inspiring for different reasons. Certain club history books stand out among the rest as well: Royal Montreal’s deep dive into its history and Mount Bruno’s where it goes through the hole-by-hole evolution are two examples.

As a bit of self promotion, I’m very proud of the Beyond The Contour team for what we put together this spring, a 352 page book that captured the best golf courses in Canada in a different manner than had been explored before. Did we rank courses? Yes, we did but I was more proud of the text that explained why certain courses fared better than other ones.

Ran, you were very complementary of it and I know you and I now see Golf Club Atlas publishing a limited series of architecture books on a range of subjects going forward.

Beyond The Contour’s book on Canadian courses

RM: What was the impetus for starting Beyond The Contour in 2021?

AH: There was a hole in Canadian golf coverage. Robert Thompson had covered golf courses in the middle 2000s, but he left that behind to develop his marketing company. Elsewhere, golf writers in the country seemed to focus on equipment and/or professional golf. As I began reading old The Canadian Golfer articles or some of the Golf Club Atlas threads on golf in Canada, I realized that there were a lot of golf courses I didn’t know about because they received next to no attention. So I took it upon myself to see as many as I could, and headed to neat courses like Waskesiu, Kenogamisis, Grand-Mere, Waterton, Digby Pines, and more.

RM: What have been the highlights since starting it? What has made you the most proud?

AH: The highlight has largely been community-based. I have made new friends who share a similar passion and have really enjoyed organizing a handful of events at places like Brantford, Lookout Point, Cabot Citrus Farms, Grand-Mere, and Norfolk, and the ensuing interaction.

Additionally, I’m very proud of the Top 100 we put together, which, when we first published it in 2022, there were 25 (!) different golf courses listed that weren’t on SCOREGolf’s national ranking. Not that I’m the biggest rankings guy, but to shine the light on twenty-five new golf courses on a national scale—and to see how much it meant to some of the facilities—was very gratifying.

Since then, it feels like the word is out on a number of places like Grand-Mere and Waskesiu that had been left out of prior conversations. I’m honoured to play a small role in Canadians learning about and seeing these special, albeit unheralded, places.

Beyond The Contour’s coverage put a well deserved spotlight on the Walter Travis & C.H. Alison design at Grand-Mere

RM: Golf Club Atlas has been in existence since 1999 and many of us have a long history with the site. Do you remember what first struck you about Golf Club Atlas?

AH: I always appreciated how people like Tom Doak, Jeff Mingay, Mike Nuzzo, Ian Andrew, Ben Cowan-Dewar, Mike Young, and countless other architects and important figures in golf were willing to give time to the site and discuss their own projects, other projects, or general architectural theory.

That’s what stood out initially about Golf Club Atlas, that a guy like Tom Doak—an industry leader and a busy man at that— was willing to peel back the layers on his career, mindset, and preferences while still being a practising architect in real time.

In forty years, people will look at the countless interesting GCA threads as a true time capsule of the second Golden Age and a blessing to have such transparent, honest, and live discussion on golf with some of the industry’s leading minds.

RM: Why are Golf Club Atlas and Beyond the Contour a good fit?

AH: Golf course architecture is a very important subject, impacting 5+ million acres in the world. Yet, it largely goes uncovered by the major media outlets.

Merging Beyond The Contour into Golf Club Atlas creates a reenergized, significant vessel for discussing this critical topic. And our approach in doing so is similar, in that we both agree on covering it in a respectful manner while highlighting the good and great golf courses around the globe. In our early conversations, we spoke a lot about a passion for the undercards—or the golf courses that get less press from the big outlets —and that was invigorating, in part because so many of these places represent great value to play. They deserve both our patronage—and money.

To combine Beyond The Contour’s modern approach and prowess with everything that Golf Club Atlas has done and brings to the table, it’s a very exciting combination that marries the best characteristics between the two websites.

RM: Golf Club Atlas turns 25 this year. What can users or visitors of the site expect in the next 25 years?

AH: An industry-leading website well into the future. There’s no doubt Golf Club Atlas has been instrumental in helping nearly everyone who’s interacted with the site grow their golf architecture knowledge, and it will continue to do so. Golf Club Atlas‘ name-recognition in the industry is well established and its future growth will be driven by fresh content across multiple media avenues beyond the written word, including video and audio. The more quality content we can produce, the more we can further the discussion of golf course architecture. And we all win.

RM: A recent thread entitled “Has Social Media killed GCA.com,” proved quite popular and interesting to read: what was your takeaway from it?

AH: Ira Fishman made a great point in the thread about how the other sections of the site—Courses by Country, Featured Interview, In My Opinion, and 147 Custodians—largely fueled the discussion board.

To some extent, gca.com undermined the vitality of gca.com. What I mean is that the other sections of the site—Courses by Country, Featured Interview, In My Opinion, and 147 Custodians—fed into and prompted good threads on the Discussion Board. Those other sections have less frequent new content. Ran properly is busy doing other things in golf architecture, and there are less of us (myself included) who make the effort to contribute to In My Opinion. It would be great to see newer courses covered in Courses by Country or interviews with up and coming architects, and I am sure that they would provoke good discussion. It is this void (perhaps too strong a term) that the Fried Egg in particular has done a good job filling.

-Ira Fishman, “Has Social Media Killed GCA.com” thread

Golf Club Atlas has to focus on quality content going forward—that will be our mission.

RM: Near term, what will be the biggest change to Golf Club Atlas that you hope to drive?

AH: A steady stream of written content will set the tone and bring the website back to its original ethos. That, paired with some modern practices—social media, video, podcast, etc.—will be the main differences in 2025.

RM: Do you believe that serious “criticism” is possible in regards to golf course architecture, considering how tight-knit, access-dependent, and sensitive the golf world is?

AH: Yes—and we are going to try! But it can be difficult, and it’s not as simple as being a restaurant critic, where the Michelin Guide has an element of anonymity for the reviewers. That did not stop us at Beyond The Contour, though. As an example, we were pretty critical of a renovation like Manoir Richelieu, because the work done in the early 2000s abandoned what made Herbert Strong’s layout so impactful, or the newly renovated TPC Toronto at Osprey Valley (North), which had the opportunity to be an invigorating renovation in the grand scheme of Canadian golf, but instead, they churned out a mundane test with lots of length but minimal playing interest. Beyond The Contour‘s own Zachary Car penned one of the more interesting, introspective looks into the current climate of golf architecture. Frank commentary was an important part of what made Beyond The Contour an interesting website, and a core part of the foundation of Golf Club Atlas as well. For sure, it will remain a vital part of the merged website moving forward.