Feature Interview No. 7 with Tom Doak

June, 2020

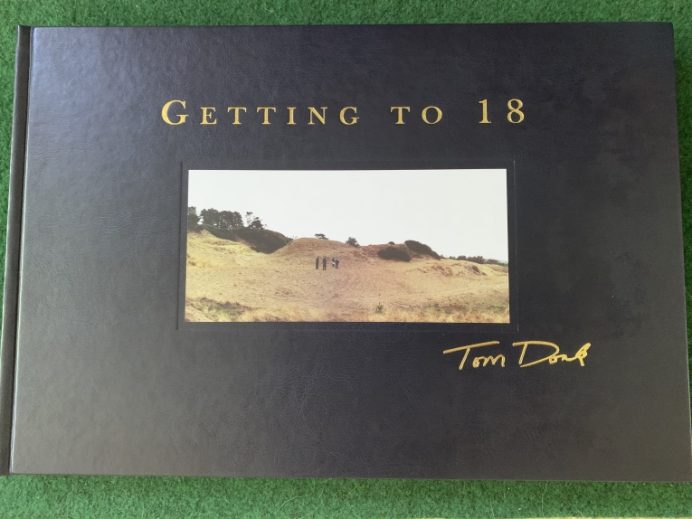

Tom Doak’s 9th book on golf course architecture, Getting to 18, ships this month and is available for purchase here: http://www.doakgolf.com/read.

When did you first come up with an idea for a book on routing a golf course?

Years ago, I tried to think what topics had not been covered well in the literature on golf architecture. The two that came to mind were (1) a detailed book on one great course and all the decisions that went into it and (2) a book on routing. Eventually, I realized they were related. It’s hard to talk about routing in general terms, because it’s all about the choices you make. So, I realized the best way to understand it was to present a bunch of case studies, where different factors were in play on different projects.

Please explain the distinction in routing in 2 dimensions versus the reality of needing to route in 3 dimensions?

I don’t spend much time thinking about the length and width of the holes when I’m doing a routing. The holes can be any length! The things that are more important are drainage and visibility, because golfers like to be able to see where they are going. [I’m not saying blind shots can’t be fun, but on the non-blind shots, you’d prefer to really see the target.] A lot of the puzzle of routing is just finding places to stop one hole close to a good place to see the next one.

Talk about your one hour lunch with Pete Dye and how that was the only ‘formal’ training you ever received on routing holes.

When I was working on the construction crew at Long Cove, Pete shared a blueprint of his routing for a new course he was working on — The Honors Course in Tennessee. Most people who have been there would just think of the site as being “on the side of a hill” as it all tilts to the west, but that tilted plane is broken up by a bunch of little rivulets where the water drains. A lot of the site was pretty steep — 5% to 8% slopes — so Pete didn’t want to have a bunch of holes playing 60 feet uphill and downhill; he wanted to play most of the holes sidehill. Routing holes along the side of the hill, his task had been to try to keep the landing areas and greens on the ridges in between the rivulets.

So, in 1981, Pete used the measure of 800 feet as the distance from a back tee to the scratch player’s landing area. [Some architects use 900 feet now; I still use 800, but it doesn’t really matter, since players are not going to wind up right where you put the post. It’s only a reference point.] But of course the ridges weren’t conveniently 800 feet apart; they were all less than that. So, how did he keep the landing areas to the high spots? Well, he would just take his scale [ruler] and draw the centerlines diagonally from one ridge to another, to try to get them close to that 800-foot mark.

Do you know how people say they could build a bridge if they could only figure out where to start? That was all I needed to get going on routing. Which was a good thing, because that was the only time I spent around Pete in the course of doing a routing. I did work on the routing for PGA West, but there was no topography there: Pete told me to roll out my tracing paper on the dining room table in Savannah, and when I did, he said: “That’s the site. It is completely flat, with mountains on the long side.” And then he drew a little cross-section of how he would build it, which was pure genius.

Anyway, I learned the rest of what I know about routing from walking hundreds of other courses and absorbing how they fit together, and from my own attempts at it.

Being able to read a topo map is crucial and this statement is quite a revelation: ‘Indeed, I think The Redan has been duplicated so much because the ridge needed is easy to spot on a topo map.’ In what decade did topo maps become an architect’s best friend? Certainly, Donald Ross was adept at routing holes from them.

An aside: I have been fascinated by maps since I was a kid. In the days before seat belt laws, my family took long car trips [from Connecticut to Missouri to visit our aunts and uncles, or to the Florida Keys so my dad could fish there], and to stop me from wrestling with my younger brother the whole way, when I was five or six, my dad appointed me the Navigator, and gave me the Road Atlas to keep track of where we were. Now, in hindsight, getting from Stamford to the Keys was not so hard — you get on I-95 and follow that, or US-301 or US-1 where the interstate wasn’t finished yet, for the whole way. But that was the start of my love affair with maps.

I really had no familiarity with topographic maps until my sophomore year of college at Cornell, but one class we had to take was surveying, which helped me understand them conceptually. It also gave me an appreciation for how much time and effort it would take to create a topo map of 200 acres from scratch, in the age before computers!

When I started High Pointe, I thought maybe I’d like to build a Redan, and it took me five minutes to find a good spot for one on the map. [All you’re looking for is a ridge that falls from right to left, and a place for a tee 180-200 yards away that’s almost level with it.] I realized that Seth Raynor probably had the same thought — although several of his, including Chicago Golf Club and Yeamans Hall, are entirely created by earthmoving. But I don’t know when using topo maps to lay out a course really became prevalent. They’re much less necessary if all the ground is open [as on all links courses], or if you are working on modifying an existing course. I’m sure Raynor and Ross used them, but I’m not so sure about Tom Simpson, and I don’t think Herbert Fowler was holding a map while on horseback at Walton Heath. So — unfortunately — topo maps became a driving force in the business right about the time it got big and architects started spending less time on site.

You would be amazed at how many modern architects cannot read a topo map very well. I was out on site with one who was used to working on flat land, on a very hilly wooded site, and he had a par-5 that was routed more than 100 feet uphill, but he did not believe me that it was that much. [I guess he didn’t look at the numbers!] Another designer told me he was going to make the bottom of a valley flat, to simplify the grading, even though it had sixty feet of fall from top to bottom! And those two have designed 100 courses between them . . .

Yikes! Conversely, talk about the limitations of topo maps. What features don’t they cover?

They won’t show you which trees are the beautiful ones that you should try and work around. [You can mark those with GPS now, if you’re not sure where they sit on the map once you’ve found them.] And the map won’t show you the views in the distance, though sometimes on a simple site you will have a good idea of them: for example, at Sebonack, I could easily know which holes would have views of the bay and which wouldn’t, even though most of the site was a tangle of vines when I did the routing.

How has analyzing land changed over the decades?

I used to ask for a topo map before visiting a site — it was a good check on whether the caller was serious enough about building a course to have spent a little money exploring it. Of course, I would make exceptions if it sounded like they knew what they were doing and I wanted to get my foot in the door. Today, someone will call from Tanzania and I can find the property on Google Earth while I’m still talking to them on the phone! It isn’t as good as having a map, but you can certainly get a sense of whether the property is worth looking at. On the down side, there’s not an easy way to ask if the caller has any money!

You’ve just walked the property and sit down for the first time with the topo map and a computer handy. How do you actually get started on the routing? What goes thru your mind (and I know it is site specific but I am after some nuts and bolts generalities)? Do you immediately look for 3 or 4 stellar, one of a kind holes that may be there, and then see how the pieces of the puzzle fit around them? Or is there some other initial process or methodology that you consistently follow?

First of all, I don’t use a computer at all when I am routing a course, I work with a map and a pencil. And if I have the map in advance, I’ll usually try to identify a few potential golf holes before I go to the site, so I can check them out instead of wandering around aimlessly, and so I have a sense of the scale of the property. Since I’ve been able to read a topo map, I’ve been pretty good at looking quickly and seeing potential golf holes. It’s really all about the proper spacing for golf shots, and how the topo lines flow together — not too close, not too far apart, trying to not hit blind over a ridge — which is why it’s important to work consistently at the same scale. [1″ to 200′, which is very close to 1:2500 in metric scale].

Your first project came at High Pointe in northern Michigan and contained 40 acres that ultimately yielded some of the best golf that you ever produced. Talk to us about the natural features of that parcel and how you incorporated them into creating five sterling holes.

First, understand that the 40-acre block of land is a staple of land development in the U.S.A. All the land to the west of the Appalachians was divided according to the Land Ordinance of 1785, into a series of townships [36 square miles], consisting of 36 sections [one square mile each], and then further divided into quarter-sections and quarters of quarters. [A quarter of a quarter section is 40 acres.] President Lincoln’s Homestead Act of 1862 allowed settlers to claim and develop a quarter section [160 acres] as their own, which is conveniently just the right size for an 18-hole golf course. So, golf development in the midwest and western U.S.A. is much easier than in India, where the government granted property one acre at a time!

High Pointe was a 320-acre parcel, in a sort of Tetris shape, with a 40-acre block at the back surrounded by state land on three sides. The front blocks were gentler, and comprised orchard and farmland, but the block in back was quite sandy and dramatic, and the vegetation was beautiful — it was as close to heathland in character as anything I’ve seen in America, to this day. From the first day I saw it, I knew I wanted to cram as many holes back there as I could.

A 40-acre block is a square that’s 1/4 mile on each side. That’s 440 yards, so you’ve got elbow room to make some decently long par-4 holes, although not really long ones since you have to allow for the back half of the green and some room behind it, so you’re really talking about 400-yard holes. And 1300 feet of width is enough for four holes side by side with some elbow room, but it’s too tight for six holes across. [Five does you no good — there’s no point in going “out” again if you can’t get back.]

The only way into that quarter section was through a valley that was the 10th fairway, and the only way out was to play down to a little ridge that became the 15th green, because it was too steep to come up the hill that way. Ultimately, my four parallel holes of 11-14 [plus the second half of the 10th] were the backbone of my plan.

Golf blossoms when played on firm surfaces whereby the ball releases. Therefore, a lot of the routing process centers on finding high, dry spots for the major playing surfaces of fairways and greens. What are three such favorite routed holes a) that you did and b) that others did?

You will find holes like that wherever you have “washboard” terrain like the land I described at The Honors Course — no matter who is the architect, really, because we all have the imperative to build a well-drained course. [On sandy ground, though, you can play holes in the valleys.] So, let’s think of a course that isn’t sandy: Pebble Beach. At Pebble, you play across valleys to fairways or greens on higher ground at #2, #3, #4, #8 [it’s a deep valley!], #9, and #16.

When I was starting to build High Pointe, I spent a lot of time at Crystal Downs, where holes like #1 and #6 and #8 and #15 re-emphasized this point to me. The 5th at High Pointe was inspired by the 15th at Crystal Downs, while the 10th at High Pointe was a bigger-scale version of the same idea.

Several of my most famous courses are sandy so I could keep the fairways and greens down in the valleys, as links courses do, but anytime I’ve built on tougher soils, you will probably find me using the washboard.

Tell us how you came to learn in the 1980s that 10% was about the maximum slope for a side sloping fairway to function properly.

When I was working for the Dyes in 1984, P.B. and I went to visit Bobby Weed in Jacksonville, and Bobby took us over to meet his friend Harrison Minchew, who was an associate in Arnold Palmer’s office. Harrison was working on a preliminary plan for the Golden Ocala project, where the concept was to copy holes from famous courses, so their client had paid to have topo maps flown for some of those courses, and when Harrison showed us those maps, I asked if he wouldn’t mind making me a blueprint copy of them — which I still have in my office.

By then I had seen all the courses in question — Merion, Oakland Hills, Oakmont, Baltrusrol, Winged Foot, and Augusta National — but having a copy of the maps allowed me to reverse-engineer some of the design work. Such as: how far uphill is too far? The most severe example of a tilted fairway I knew that worked well was the 5th at Merion, and now I had a topo map so I could measure what the slope was on that fairway.

Given the new grasses and how much tighter fairways can be presented today versus ~30 years ago, what is max tilt in a fairway today that you find conducive to good golf?

I still think of 10% as the maximum, although if the whole fairway was 10%, that wouldn’t work now. You need areas to vary between 5% and 10% if you want the ball to settle in different spots, with a sidehill stance. The crucial part is, what’s above and below the fairway? If those areas are more than 10%, then the fairway had better be a bit flatter. If the ground to the sides is flatter, then you can put the fairway on the side of the hill without much concern, because it will still be playable even if the ball rolls out of the short grass.

One of the routing lessons from Getting to 18 is that there are no rules. Talk about three of your holes that fly in the face of ‘conventional’ wisdom.

There are lots of courses in America that play downhill off the tee and uphill to the green, to get you to that elevated tee for the next hole. One way to break up that monotony is to have a hole that plays up and over — uphill on the tee shot, and downhill to the green. Bill Coore is the master of those. I’m not a natural for seeing those holes, I really have to look for them. The most dramatic example of that type is the 4th hole at Royal Melbourne (West) — which I have shamelessly imitated at Stonewall (North) and a couple of other courses.

I have been lucky to build a lot of courses on sandy sites, where you don’t have to worry about drainage, and the best way to capitalize on that is to build some greens and fairways in valleys, where you could never put them if you were building on heavy clay. Nearly every fairway at Ballyneal or Barnbougle is in a valley, and many of the greens are surrounded by tightly-mown banks, which you can use as backstops to bring your ball back to the hole.

Lastly, when we built Old Macdonald, I noticed how much different the standard was for an “old” course than for a new one. If I’d asked Mike Keiser when we were building Pacific Dunes to let me build a blind tee shot like the 3rd at Old Mac, or a blind approach like the 16th, he would have said “no way,” but when we said that’s what Macdonald would have done, there was no argument. And those are two of the most talked-about holes, because they set the course apart from the others in Bandon.

Your two flattest sites to date have been Heathland in North Myrtle Beach, South Carolina and the Rawls Course in Lubbock, Texas. Talk about how you approached each in a different manner.

From the beginning, my client in Myrtle Beach talked about building a “Scottish-style” course — in fact, he got my name from the Scottish golf photographer, Brian Morgan. Since the topography was minimal, I had to get the site to drain, and then I went to my file of cool holes I’d seen in the UK to find some that would work on a flattish site.

The site in Lubbock was even flatter, but it was also heavy clay, so building linksy features in valleys was not going to fly. And there were no sand dunes in the vicinity to mimic! Instead, we tried to make the grading look like the golf course had been cut down into the ground by (water) erosion, and so you will find some “washboard” holes there.

What is an example of sandy loam providing you options in a routing process that clay would have precluded?

Sandy loam is a great growing medium, but some of my best courses are on pure sand, where you don’t have to worry about a fairway right in the bottom of a pocket that doesn’t surface drain anywhere. Think of that narrow landing area for the 8th at Ballyneal, or the 7th green just before that, in its own little valley, with a bunch of short grass to the left of the green feeding down onto it. Or the 4th at Barnbougle, with the fairway in the lowest point, and the green in its own little bowl that doesn’t drain anywhere. As Mike Young likes to point out on the GCA Discussion Group, he’s never been able to build anything like that, because you just can’t go there on clay. So, where we can, I make the most of the opportunity.

You state, ‘Projects were only guaranteed to succeed if there was a single client with the power to say yes – or even no – to what we wanted to do.’ Mike Keiser immediately springs to mind and Pacific Dunes was a game changer for your career. Of the owners with whom you have worked, what % would have proceeded with the unconventional sequencing of pars at Pacific Dunes, especially the second nine which reads 3-3-5-4-3-5-4-3-5?

Mr. Keiser had been concerned about par on my previous routing for Pacific Dunes, where one nine was par-34 and the other was par-37. [That was the same at High Pointe, and golfers didn’t seem to care.] But we walked the final routing for Pacific Dunes one morning after I had rearranged it the night before, and I honestly hadn’t thought about what the scorecard would look like. Everyone was thrilled with how it flowed, but then over lunch, I started jotting down the scorecard on a napkin and realized what it looked like, and held my breath when I slid the napkin over to Mike to ask him if that was okay. Luckily, he’d already fallen in love with it by then, so it was a good thing we walked it first!

Probably 50% of my clients have asked if I couldn’t modify my routing a bit to change par, or make it more balanced, or get the course to come back to the clubhouse at the ninth hole. Conventional wisdom is just whispering in their ears. And it does in mine, too! But I’ve gotten where I am by ignoring some of those rules, and especially in the last few years, clients understand that and tend not to worry about convention, either. Some of my best clients like Rupert O’Neal and Richard Sattler were not golfers, so there was never any concern about that kind of stuff — they just told me to make sure it was fun.

Your original routing for Pacific Dunes became a non-starter once it was evident that David McLay Kidd’s final routing of holes 5-7 for Bandon Dunes made a series of your holes impossible. How good was that course that you came up with originally versus what was ultimately built at Pacific Dunes? Put another way, was it fortuitous that Bandon Dunes ended up extending as far north as it did?

For sure. Mike acquired the Schumann property when David was halfway through construction on Bandon Dunes, and he let David re-route his front nine to use the land that includes #5 green and #6. When I confessed that I was struggling because I’d lost some of that land, Mike volunteered that he had bought the ground north of Schumann’s property, too, and maybe I could borrow a bit of that. And that’s where we found the 13th hole at Pacific Dunes, just laying there waiting for us. Giving up #6 at Bandon for #13 at Pacific is a trade I’d make any day.

What routing puzzle took you the longest to solve? Is that the same as saying that was the most difficult piece of property upon which to settle on 18 holes?

The North Course at Stonewall took a long time, because we were exploring which pieces of property the club should buy to complete it. I think I did more plans for that one than for anything else. The Village Club at Sands Point also took a long time, because local politics kept sticking its nose into things, and forcing another change.

But the ones that took the longest will have to wait for a future book: Ballyneal, Rock Creek, and the one I’m working on now, St. Patrick’s.

When I was trying to route Ballyneal, we were really busy building in Australia and New Zealand and also planning Stone Eagle and Sebonack, so I would only stop through for a couple of days at a time, and I kept having to leave and head for the airport before I could get to the 18th!

At St. Patrick’s it was much the same — I would visit for a couple of days and get a few things figured out, but then I’d have to leave and put it on the shelf for a few months. I did that over 3-4 years all told. When the last part of it came together — the loop of 3-4-5-6 — Eric and I were actually leaving the property to head home, and we got up to the 4th tee on our way out and I suddenly thought about working counter-clockwise for that piece instead of clockwise, and we went back and spent another hour and a half sorting out the final plan.

Though Rock Creek isn’t covered in this book, you mention it above so let’s talk about it. Its property was expansive, to say the least! Is it reasonable to assume that a site like that where holes can go in a ~zillion directions is more taxing to route than a Barnbougle Dunes where the property is narrow and you knew holes wouldn’t wander into the flat for too long?

At Rock Creek, we had 80,000 acres to consider. A lot of it was too steep or too dull, but even so, I didn’t set foot on the site where the golf course is today until my third trip out there. Eventually, I narrowed down the search to four square miles of rugged land that had just the right contours for golf, and I had those maps laid out on the floor of my office for a month trying to sort it out. My wife used to make fun of me for working on the floor, but we didn’t have a table big enough. (I wish she’d taken a picture of me at work.)

At Barnbougle, or any site where the acreage is restricted, the corridors for golf holes are pretty clearly defined by the topography. Almost the whole routing runs east-west, which isn’t ideal, but if you tried to play north-south you’d have to hurdle a couple of blind ridges, and after 300 yards you’d wind up in the potato fields or the river! So you’re only trying to sort out whether to wander the valleys clockwise or counter-clockwise, and exactly where to make the breaks for greens and tees. But when you’ve got to fly 9,800 miles to go check out the possibilities, you make progress in fits and starts.

Is there a single routing that best unlocks the full potential of a site? Or do feature rich sites generally yield several plus routing outcomes that would have nearly the same appeal? I ask because Barnbougle seems perfect ‘as is’ and yet, when I read about your initial vision of having the 18th play backwards a la 1 at Machrihanish, I start to wonder!

As I state in the book, I tend not to develop multiple alternatives for the routing — I’ll only present the one I like the best to the client, and if I’m trying to improve it, I’ll generally stick to working on one section of holes at a time, as opposed to reversing everything. But, better land is going to yield better possibilities, and the “best” routing is ultimately a matter of opinion.

You have built (at least in your mind) some great holes that never made it to fruition. Please describe one of them.

The book describes in detail my original plan for the 13th hole at Cape Kidnappers, with a green site hanging off the side of the cliff, 100 feet below the present green. The hole would have completely overshadowed the rest of the course, and ultimately, that’s part of the reason we decided not to build it.

You have routed courses in five different decades. Does it become easier with time as you solve one puzzle after another after another? Is there something that you learned from routing courses 2010 to 2019 that you wished you had known in the 1990s?

The puzzle part certainly gets easier the more of them that you do, just like the New York Times Sunday Crossword. That’s the whole premise of the book, really; you learn by doing, and hardly anyone [even those of us in the business] gets enough practice to be really good at it. It might have been 2009 and not 2010, but for sure, collaborating with Bill Coore on the routing for Streamsong and seeing how he approached things differently, made me better at routing. So I was really honored to have Bill write a foreword for my book. He also provided his routing plan for The Sheep Ranch so I could analyze what he’d done differently there.

Sounds like having Bill Coore ‘live and in person’ at Streamsong must have been both fun and educational. How about some of the Golden Age guys who aren’t around for you to engage? You mention the up and over 4th at Royal Melbourne so I know you have learned from your years of studying Alister MacKenzie. Do any other Golden Age architects in particular impress you with their ability to route?

Streamsong isn’t in this book, so I only teased at what I observed watching Bill there, and how different his process is than mine. Hopefully someday I’ll get around to writing about that one in more detail.

As for the Golden Age designers, they all had to be pretty good at routing courses, since they didn’t have the budgets to try and fix their mistakes with earthmoving. But I can’t say I’ve really made a study of how Ross and Tillinghast and MacKenzie routed courses, and what they did differently. I know Ross worked with a lot of rectangular sites, and he was very good at orienting some holes on the diagonal to break up the monotony of parallel fairways.

I do think I have learned a lot about routing intuitively, just by walking so many golf courses over the years. For the majority of them, I didn’t look at a map before I headed out, and if they were busy at all I might not walk them in order. So right from the start I am looking around and trying to puzzle out which hole is which, and how it’s going to get back to the clubhouse. I’m sure that has helped me in understanding what won’t work on a new map, and stopped me from wasting time on solutions that will be dead ends. One of the truths of routing is, for any given site, you have to get to 18.

Is that shame that you have to get to 18? It is certainly a forced contrivance by man, somewhat driven by the handicap system, and is a major departure from how golf started out with 5, 6, 7, 9 and 12 hole courses 170 years ago. What if a 140 acre site would yield a fabulous 14 hole course or a more conventional, cramped 18 hole one? What would you recommend to the owner?

The premise of your question is off, because if there is only room for 14 great holes, then the 18-hole solution is likely to be less conventional, in having to deal with the lack of space. It might be a par-64, like Audubon Park in New Orleans. Or utilize crossovers, to steal some yardage by double-using a space. I’ve drawn some pretty wild things like that over the years, for projects that ultimately didn’t get built.

One of the best trends in modern golf is that courses like Bandon Preserve and The Mulligan at Ballyneal have broken down the barriers a bit — they aren’t 18 holes, and nobody cares one bit. But, they’re side dishes, and not the main course. Will American golfers ever accept a 15-hole course instead of 18? It will be a very tough sell.

From the standpoint of a guy who does the routing, finding the best 18 holes is the only way to judge how well I’ve done. If I could have any number of holes, how do I decide where to stop? Is 16 automatically better than 15? [If so, why not 20?] Most people are going to get to 18, unless the property is just too small — and then I think most would suggest 12 holes, instead of a random number in between. Personally, if I couldn’t find 18, I would be happy with 14 or 15 or 16, but I don’t think most clients would agree.

I know that Edwin Roald has done courses with odd numbers of holes in Iceland and it’s apparently been accepted — but in Iceland, people are not as attached to posting their score as they are in America, or Australia, or the Far East.

But maybe it’s the other way around? Golfers are so focused on posting an 18-hole score BECAUSE designers and developers insist on building them, and if we would let go, golfers would be happy to follow.

I would love to see an owner step up on a primary course and let you run with whatever number holes was optimal for the site. Moving on, not many people can answer this question so we are compelled to ask it: What is it like to grind on a routing for weeks and ultimately come up with one that you are confident gets the most from the property? Are you chuffed? Relieved? Exhausted? Satisfied? Does doubt ever entirely leave your mind?

I’m excited, because if I’m happy with the solution, that means I think it’s going to be a special course. If I didn’t think so, I’d still be working on the routing.

One hundred + architects will read this Feature Interview. What three tips would you give them regarding routing a course that you have learned through trial and error over the past forty years?

Number one, forget convention, or even defy it. That will call attention to your work. But, if you’re going to defy convention, the result had better be worth putting up with the naysayers.

Number two, don’t get serious about doing a routing until you really understand all the constraints you have to work under. The worst feeling in the world is to lay out some holes you like, and then have to give them up because of a wetland issue, or because somebody finds some pottery shards, or the neighbors threaten to sue over a stray golf ball.

But by far the most important advice is, take your time at it, and enlist some trusted people to comment along the way. A good golf course routing lasts forever, so you shouldn’t try to get it done in a certain time frame. I’ve done a couple of courses [St. Andrews Beach and Sebonack] where my very first routing was bulletproof, but for many of my best routings I had a few months to get away from them, and then some good feedback from the client or one of my associates, so I could look at it with fresh eyes to see what might be improved.

And to follow that up, the routing is not done until the last hole is grassed, so don’t be afraid to move a green site in the field after you’ve started construction. The longer you spend out there, the better you know the ground, and the more possibilities you’ll see. There are limits to what sorts of changes you can make, depending on the permitting issues, but just as examples, the 2nd and 18th greens at Pacific Dunes were moved between the final plan and completion, and the 7th at Ballyneal and the 7th at Barnbougle and the 18th at Stonewall (Old) are all significantly different than the plan I started with.

The End