Feature Interview with Dunlop White Part II

March 2005

Having graduated from the School of Law at Wake Forest University, White practices real estate title work in Winston-Salem, North Carolina. White serves as an officer of the Donald Ross Society and is also an architecture and design panelist for Golfweek’s ‘America’s Best Courses’ and North Carolina Magazine’s ‘Top 100’. As a writer, White’s treatises serve as crucial pieces of literature for superintendents and green committees and have been featured in a variety of golf publications, including LINKS, Golfweek, Superintendent News, Triad Golf Today, North Carolina Business, and Paul Daley’s cult classic, Golf Architecture: A Worldwide Perspective. As an enthusiast of classical golf course restoration, White is an ardent conspirator of tree management and believes that such a commitment is critical for those clubs who want to reclaim their architectural integrity.

10. Discuss the many issues of integrating trees for safety and protection purposes.

Some courts have found that various sports, including golf, are ”inherently dangerous”. The fact that golf balls can go astray and take unintended flight patterns which may cause injury is a ‘recognized and understood risk of the game’. Therefore, when participants voluntarily encounter such a ”known” danger, they have ‘assumed the risk’ of harm simply by participating — thereby relieving the club from any liability of negligence.

There are many debatable questions that must be asked when determining whether trees should be utilized as safety buffers on golf courses. Admittedly, trees shield golfers in many situations, but not always. For instance, how many times have you witnessed rows of midget evergreens dividing holes? Do they really protect golfers? Larger hardwoods are fine, but aren’t golfers just as susceptible to the ricochet? The point being that there is a false sense of security associated with trees, which separate holes. Despite their ineffectiveness, many courts tend to view tree plantings as a club’s good faith effort to safeguard both golfers and adjoining property owners.

Some states do not permit an ”assumption of risk” defense. Instead, these jurisdictions treat it as a question of ”duty” for the country club. In other words, do clubs owe a reasonable duty of care to golfers to reduce the risk of injury on their golf courses? Many courts have held that clubs do, in fact, have an obligation to minimize the risk of players getting hit by golf balls by the way various trees, fairways and greens are aligned and separated. Such minimization may require that clubs provide tree protection for players in high traffic areas where ”the greatest dangers exist and where the occurrence is reasonably foreseeable”. Testimony of prior incidents and a propensity to err in a certain location can put the club on ‘notice’ to do something to reduce the potential for harm. Here, clubs will not be able to hide behind a cloak of ignorance.

Other courts have ruled that clubs are under no legal duty to eliminate risks inherent in the game, but they do have the duty not to increase the risks. That’s exactly what one club did when a tree was removed from the course opening up an area for a wayward shot, which normally could have been deflected by the tree. This court apparently rejected a good argument by the defense that open, unobstructed site-lines can create a visual awareness or consciousness between groups, where golfers can easily be spotted, judge when to hit and not to hit, and forewarn others of an errant shot. They argued that golfers couldn’t always forewarn neighboring groups of an impending shot when they are obscured by trees and therefore cannot be seen.

Today’s innovative golf equipment has rendered golfers more vulnerable to being struck by errant shots throughout intimately routed classical golf courses. Titanium drivers and graphite shafts combine to make higher compression golf balls travel further distances — both on and off line. Tree screening, however, isn’t the only defense for every shrinking hole. Other design techniques are available to reduce risks of injury. When there’s room available, clubs ordinarily extend tee boxes, shift their positions, and realign them, so golfers will aim further away from a bombshell area. Shifting hazards and fairways can also help re-define the line of play. While numerous clubs have acted responsibly in planting trees for protection, many more have over-reacted — erring on the cautious side — due to safety and liability concerns on golf courses.

11. Describe some preferred tree care and conditioning practices on golf courses.

Clubs may find it beneficial to inventory and catalogue trees throughout the golf course. Typically, a certified arborist will identify the various tree species on a course, chart their locations, evaluate their condition, and determine their ages and life expectancies. This is valuable information in order to prioritize tree care and plan for attrition.

An annual tree evaluation should include more than isolated tree removal. The inspection should include corrective pruning measures, such as ”dead wooding”, ”crown thinning”, and ”crown reduction”. ”Dead wooding” involves the removal of dead, diseased and decaying wood and other hazardous branches, especially on older trees. Hanging limbs can pose imminent safety dangers. ”Crown thinning” involves highlighting the primary pillar branches in the tree by removing excessive secondary branching which filter light and air circulation. ”Crown reduction” involves controlling the overall size of the canopy. Here, ”heading” is a method of cutting the primary branches back to stubs — usually done in situations where the tree has outgrown its welcome or in congested areas where canopies merge and awkwardly compete for sunlight, air, and water.

A certified arborist is also qualified to recommend fertility programs, irrigation solutions, and disease and pest management needs for ailing trees. Modern horticulture programs utilize advanced diagnostics, including aerial infrared photography, vertical mulching, root pruning, deep root fertilizing, large spray operations, and even tree injections. Lightning protection units and cable wire suspension systems can also be affixed to tree appendages to reduce the potential safety hazards caused by wind and hazardous weather. The idea is that trees can play an important role on golf courses and their condition and care should be carefully managed.

12. What does the practice of ‘tree management’ entail?

As golf courses have evolved, it is hard to determine which have been more damaging — newly planted saplings or mature hardwoods that have not been kept at bay. Trees continuously change height, width, and shape, which may negatively impact a golf hole. As such, trees must constantly be accessed, pruned, and removed. It all depends on the type of tree, its structure, and its relationship to critical golf course features.

Ultimately, judicious tree management is the process of evaluating how various tree species interact with their surroundings in the following contexts:

- Course Strategy: How do trees affect the strategic playability of golf holes?

- Agronomics and Conditioning: How do trees impact surrounding turf quality?

- Aesthetic Landscaping: How are trees situated to enhance and/or camouflage potential perspectives and views?

- Safety: How are trees positioned to protect golfers from errant shots?

- Health and Physical Condition: Whether trees need some tender loving care?

Out in the field, the interpretation and application of these principles are not cut and dry, no pun intended. Dilemmas always arise and important decisions have to be made. Clubs often toil over trees that serve contrasting functions. For instance, what if a hardwood is located in a strategically improper location yet is an elegant specimen that serves as a safety buffer for an adjoining hole? What if a cluster of evergreens shades a struggling green site yet partitions the course from the objectionable sights and sounds of a neighboring freeway? What if a decaying hardwood is an eyesore but offers shelter and harbors a food source for endangered woodpeckers and nuthatches?

13. Who should perform the various tree work on golf courses?

There is a distinct difference between ‘tree care programs’ and ‘tree management plans’ and who is ultimately qualified to perform the work. Typically, certified arborists, horticulturists, and trained superintendents will assess the physical condition, health, and well being of trees and complete small-scale pruning and removal operations. Climbing, bucket work, and major tree removals are typically performed by outside contractors. By themselves, however, arborists and horticulturists are not qualified to carry out a tree management plan, as proper evaluation would include more than an inventory and exercise in tree care. Rather, golf course architects with restoration experience have emerged as the most informed and qualified authorities in the field. Today, architects will evaluate how trees integrate with their surroundings in the contexts of golf course strategy, aesthetics, agronomy, recovery play, and safety. Sometimes, consulting USGA agronomists are capable of fulfilling a club’s tree management needs. Both are much more influential and persuasive than superintendents and green committees simply because they don’t have a personal interest or agenda in club politics.

However, it’s important for superintendents to supervise and monitor the removal process. While it’s easy to gauge limbs and trees for removal at the outset, architects cannot always ‘get it right’ unless they are on the scene everyday inspecting the removal process one limb at a time. Clubs are more likely to achieve an anticipated look if a superintendent is empowered to render judgments as the action unfolds.

I truly believe tree management is a team effort. The architect writes the script, the superintendent directs it, and the green chairman produces it for the membership. Each part is integral to the process, all serving as checks and balances on one another.

14. Describe some successful tree removal tactics, which help evade the emotional landmine of club politics.

Golfers simply adore trees. Tillinghast once said, ‘I sometimes take my very life in my hands when I suggest that a certain tree happens to be spoiling a pretty good golf hole.’ Architect, C. H. Alison, agreed that Americans were always ‘enthusiastic tree preservers and planters.’ The mass proliferation of trees that encumber our golf courses today serves as proof. It’s not difficult to discern the prevailing sentiment. An alarmed member once approached our superintendent and inquired, ‘Why did you remove those poplars?’ The superintendent responded, ‘Because the they were dying.’ The member exclaimed, ‘Well I’m dying too — I suppose you’d like to take me down as well?’ Most so-called tree huggers hold a perverse emotional attachment to trees.

There are a number of ways to ‘stump’ the opposition. Most importantly, don’t notify or alert the membership. Slip-up and mark a tree for removal with an orange ribbon or a surveyor’s flag, and enraged golfers will stalk you down in protest. An ‘X’ drawn on the tree trunk with red spray paint is much too conspicuous as well. Unless it is an outright specimen, don’t bother trimming overgrown trees either. The wound typically leaves an apparent scar to remind all golfers of your exploits. More often than not, the best place to trim a tree is right down at the base.

Begin tree removal on the interior of the course, as opposed to the holes adjacent to the clubhouse or roadways, to avoid early detection. The best time to remove trees is when the club is closed or when no one is around. If trees are removed in the middle of winter, no one will usually notice the next spring. Similarly, if trees are removed in the dead of night, no one will likely miss the trees the very next day.

Case in point: historic Oakmont Country Club just outside of Pittsburgh, (Pa.). Throughout the 1990’s while members were home asleep, superintendent, Mark Kuhns, supervised a small squadron armed with high-powered spotlights and a battalion of eighteen-inch chainsaws as part of their Board sanctioned operation to remove trees in the pre-dawn hours. Chippers, stump grinders, tarps, vacuums, and fresh sod were all brought along to tidy up the mess. As they cut deeper through the impinging hardwoods, Oakmont rediscovered the innate beauty and genius of Henry Fownes’ 1903 masterpiece long before the membership detected or noticed any transgressions. As a critical part of their long range restoration plan, Oakmont — site of the 2007 United States Open and home of 13 USGA national championships — eventually removed over 4,500 trees, leaving only 68 specimen hardwoods standing.

”]![At daybreak, superintendent Mark Kuhns watches trees fall behind the 'Church Pew' bunker at Oakmont Country Club in the early 1990's. [By: Mark S. Murphy of Golf Digest]](https://golfclubatlas.com/images/DWOakmont.jpg)

With tree removal, a discrete and methodical approach builds consensus. Do not send the membership into a state of shock or panic. Prioritize and start removing judiciously. By the time members start noticing tree loss, they will be supporting an agenda that they never would have honored at the outset. Typically, members who are emotionally attached to hardwoods are the ones taking credit for their removal once they have ‘mysteriously’ disappeared.

Superintendents should also be prepared to answer membership inquiries. As clublore goes, a superintendent once nicknamed his two McCullough chainsaws, ”Ice” and ”Lightning”. As tree loss became apparent over time, the superintendent honestly reported that ice and lightning destroyed the missing trees during the last storm.

In dire situations, copper nails and toxic chemical applications are fine choices to promote a slow departure. Ordinarily, members don’t object to the removal of rotten, brown hardwoods once they have inexplicably perished. Golfers will offer good riddance when these trees become unsightly and pose imminent safety hazards.

15. What are the most successful methods of cultivating membership support for tree removal?

Education! Show the membership the archival material — the topos, the overhead photos and the design plan — and trace the evolution of tree plantings and tree growth throughout the golf course. Stimulate a greater sense of appreciation for your architectural heritage. Convert revealing aerial photographs, evocative of the open nature of the original design, into informal placemats for all members to examine before meals or after rounds. Hire expert witnesses, who don’t have a personal interest or agenda in club politics, to give talks, slide shows, and/or PowerPoint presentations to the membership on the benefits of tree removal.

Prepare other appropriate visual displays for the membership. Photographic evidence is an excellent way of ”logging” support and patronage from your membership. Other courses, which have embarked upon tree management programs, have taken series of ”before-and-after” photos and the results can be quite convincing. For example, look at the remarkable transformation below when an understory of evergreen saplings was removed from this dense woodland area.

Before:Thick vertical walls of vegetation outlined the fairway on Hole 8 at Roaring Gap Club (NC), a Ross relic in the North Carolina mountains.

After:Here, tree management involved extracting volunteer evergreens and impinging vegetation from the understory, a process that brought to view magnificent hardwoods and provided room for recovery play.

While the digital camera is a great tool for capturing ‘before-and-after’ comparisons, Adobe Photoshop software allows you to edit a current image of your course to assess how tree removal would look at a specific location in question. These are called ‘now-and-future’ comparisons, which can be equally persuasive.

Now:Because of tree encroachment to the right, only the left half of the tee box could be used on Hole 6 at Roaring Gap Club (NC) in 2004.

Future:With Adobe Photoshop editing software, I peeled back the overgrowth on both sides of the tee to offer a sneak preview of how the hole would look with full scale playing lanes and site-lines through the green on Hole 6 at Roaring Gap Club (NC).

A negotiable approach is advised where club democracies demand membership approval and consent. Because members are more concerned with good agronomics than with strategic shot making, it would be good politics to approach tree removal with the emphasis on the ability to grow healthy turfgrass. Architectural principals are generally less accepted as justifications for tree removal. Focus instead on course conditioning.

For instance, if you explain that the tree was removed from behind the green because the grass was brown or because its roots were penetrating into the fill pad, then you will ordinarily satisfy those who are most alarmed. However, if you try to convince a committee that the tree was unoriginal, unattractive, unduly penal, or strategically improper, you had better hide beneath that very tree for cover.

Also, never refer to the operation as a ‘tree removal program’. Instead, label the project, as a ‘tree management program’ or a ‘light enhancement program’ and members will less likely resist.

Compromises work just as well. Golfers, who are sentimental about trees, ordinarily appreciate flower gardens and other formalized beds adorning the premises. Focus on such arrangements in conspicuous sections around the clubhouse. Thus, if you erect a shrub bed beside the parking lot, you will not appear as ecologically insensitive for logging a few menacing trees on the golf course.

Committees should always endeavor to reassure their members and limit their initial fears by transplanting trees at the beginning of a project. A preliminary presentation of tree care is essential. Relocating smaller trees into proper places on a golf course is a successful political tactic if implemented at the outset of the program.

Also, never divulge the actual number of trees designated for removal. Initially, three hundred (300) trees sounds devastating and will likely send shock waves throughout the club. Most members, however, do not realize that an average golf course contains between 20,000 and 30,000 trees. It is better not to explain. Instead, hedge significantly to the downside if disclosing the actual numbers.

16. Describe the principal challenges involved with clear-cutting.

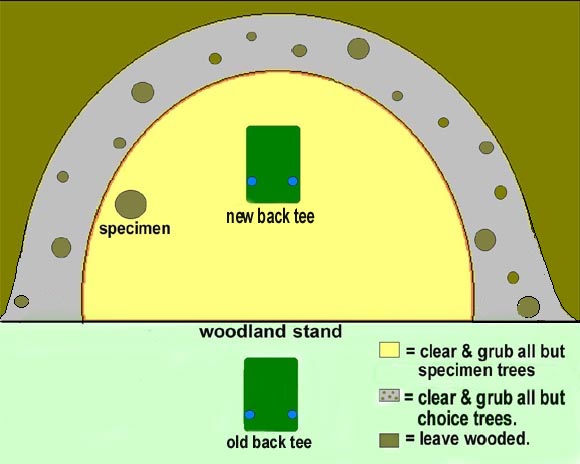

When clear-cutting through woodland areas, make sure the opening corridor is large enough, and the ensuing tree line has a natural, loose-fitting shape to it. Try to avoid slicing your way through a forest, resulting in one-dimensional, vertical walls of foliage. As a rule of thumb, mark two rough perimeters for clear-cutting — an outer-perimeter and an inner-perimeter. Between perimeters, clear-and-grub all but choice, hand-selected hardwoods. Here, look to retain some of the finer trees. Be more selective within the inner-perimeter, which should be cleared-and-grubbed of all vegetation, except bona-fide specimens. Here, only the cream-of-the-crop should be salvaged and integrated into the golf hole, if possible. Clear-cutting is an art form. You simply don’t clear away everything in your path as the term implies. Today, making room for new back tee boxes for extra yardage often requires clear-cutting through a woodland stand behind the hole. See the diagram below for an illustration. Also, don’t forget to sell the lumber.

17. What are the advantages of tree transplantation?

If a strategically important tree dies, don’t let it ruin your golf hole. Instead of replacing it with a smaller version from a commercial nursery, why not hire a tree spade service to transplant one of similar size and structure from another part of your golf course? As an oversimplification, the tree spade basically scoops up the entire tree and secures the rootball. Then, a crane transports the upright tree to its new home where an excavator has prepared a hole for it to be planted. There are many instances where tree relocation can be beneficial. First of all, the savings are extraordinary. The cost of purchasing a new tree can be an expensive proposition. For instance, an oak with a 12-inch trunk runs about $3,000.00, plus installation, which totals about $4,000.00. In contrast, tree-transplanting fees run about $2,000.00 per day, a savings in itself. But potentially three trees can be moved in a single day.

18. List some of the dos and don’ts when planting trees.

- Avoid planting trees too close to bunkers or other hazards. Together they would create a double hazard.

- Avoid planting trees that block clear visuals of bunkers, creeks, and other hazards. Hazards should stand prominent in the mind’s eye.

- Plant trees in distinct groupings or self-contained clusters. Scattered trees typically make a mess of open spaces.

- Within these groupings or clusters, plant trees far enough apart as to prevent competition (tropism). Also, plant varieties of deciduous trees. Disease, therefore, may kill one without spoiling the entire grouping.

- Don’t plant low-limbed, evergreen species, such as eastern white pines, hemlocks, spruces, cedars, and firs. They possess shallow surface roots, a maintenance burden. They also block air, sunlight, fair opportunities for recovery, and desirable cross-course vistas.

- Favor tree plantings on the perimeter of the premises to partition unattractive structures and noise. Favor tree removal on the interior of the golf course to expose beautiful sweeping perspectives.

- Avoid planting trees in formal arrangements, such as rows of trees between fairways. A single-file, row of trees appears contrived and forced in a natural landscape. Plus the loss of a single tree destroys the form created.

- Tree plantings are accepted to the north or west sides of play as opposed to the south and east sides, which block critical turfgrass areas from receiving exposure to essential morning sunlight.

- Don’t plant trees in close proximity to grand hardwoods. Bring to view the specimens.

- Avoid planting trees to the inside corners of doglegs or abutting typical landing areas. Blocking corner angles and squeezing landing areas promotes target golf; therefore, these locations are to be avoided. Instead, peripheral trees may be planted between typical hitting areas and typical landing areas. Here, trees cannot obstruct or stymie the next shot. Rather, they will affect the curvature or trajectory of the next shot in proportion to the error of the drive. Thus, planting peripheral trees before and beyond typical landing areas advances the classical attributes of strategic shot making.

- It’s always good advice to avoid planting memorial trees. Allow one, and soon your course will be inundated with them. Someone once said that the best way to honor loved ones is to take a few trees down in their name instead.

- Avoid planting trees behind every green. For variety, a framework of trees does not need to shore-up all backdrops. Boundless vistas enhance the visual challenge of determining the depth and distance to the hole.

19. What proved to be the most valuable sources of information as you compiled your tree thesis?

- ‘Trees on Golf Courses: Do they Really Belong?’, Rough Meditations, page 69, 1997, by Bradley S. Klein, Sleeping Bear Press, Chelsea, Michigan, USA

- ‘Proud, Tree Loving Golf Host Often Out of their Tree’, Golfweek, page 46, August 18, 2002 by Bradley S. Klein, Turnstile Publishing Company, Orlando, Florida, USA

- ‘Reversing the Tree Planting Trend’, Superintendent News, November 9, 2001 by Jeffrey D. Brauer, Turnstile Publishing Company, Orlando, Florida, USA

- ‘Transform Boring Targets by Removing Backdrops’, Golfweek, November 2001, by Bradley Anderson Turnstile Publishing Company, Orlando, Florida, USA

- ‘Tree logic: If it’s in the game’s way, take it down’, Superintendent News, November 10, 2000, by Bradley S. Klein, Turnstile Publishing Company, Orlando, Florida, USA

- ‘Vegetation as a Hazard’, Anatomy of a Golf Course, page 176- 185, 1992, by Tom Doak, Burford Books, Short Hills, New Jersey, USA

- ‘William Stephen Flynn’, The Golden Age of Golf Design, page 114, 1999, by Geoff Shackelford, Sleeping Bear Press, Chelsea, Michigan, USA

- Golf Course Architecture: Design, Construction and Restoration, Page 94, 1996, By Michael J. Hurzdan, Sleeping Bear Press, Chelsea, Michigan, USA

- ‘Strategic Open Space Gives Choices’, Golfweek, March 13, 2000, by Jeff Mingay, Turnstile Publishing Company, Orlando, Florida, USA

- ‘Trees on the Golf Course’, Golf Illustrated, 1928, by A. W. Tillinghast

- ‘A Year’s Worth of Design Distinctions’, Golfweek, page 46, March 13, 2000 by Bradley S. Klein, Turnstile Publishing Company, Orlando, Florida, USA

- ‘Mission Unpopular’, Golf Digest, page 100, October 2002, by Peter McCleery and Mark S. Murphy

- ‘Developing a Tree Care Program’, USGA Green Section Record, March/April 1996, by James Shorulski

- ‘Root of all Evil: This Old Course’, Sports Illustrated: Golf Plus, June 5, 2001, by John Garrity

- ‘Agronomy: Operation Lumberjack’, Superintedent News, 1999, by Bradley S. Klein, 1999.

- ‘Trees’, Golfclubatlas.com, December 12, 2004, by Tom MacWood

- ‘Avoiding Legal Sandtraps on the Golf Course – How Liability is Apportioned for Golfer’s Bad Shots’, Willamette Sports Law Journal, Winter 2004, by Lincoln Scoffield

- ‘The 85th PGA Championship: Who and What to Watch For’, Sports Illustrated, by Sal Johnson, August 11, 2003

- ‘The Tree Mission: Getting Back to Roots’, The BoardRoom Magazine, page 10, Vol. VII, Issue 65, by John G. Fornaro.

The End