Feature Interview with Bradley S. Klein No. II

July 2001

Bradley S. Klein of Bloomfield, Conn., has just published Discovering Donald Ross: the Architect and his Golf Courses (Sleeping Bear Press, 415 pages). He is editor of Golfweek’s Superintendent News and architecture columnist for Golfweek, where he runs that magazine’s ‘America’s Best’ lists of top-100 Classical (before 1960) and top-100 Modern (1960 and after) courses. He is also the author of Rough Meditations (Sleeping Bear Press, 1997), a collection of essays about course architecture. A former PGA Tour caddie, he holds a Ph.D. in political science and taught at the university level for 14 years before ‘retiring’ in 1999. Klein carries a 15 handicap and is a member of Wampanoag CC, Conn. and Royal Dornoch Golf Club.

1. How did you go about researching a design biography of Ross?

It took three years, which is long by golf writing standards but not by academic standards, and I took a more academic approach. I made about a dozen trips to the Tufts Archives in Pinehurst, spent a week in Dornoch, visited about 100 Ross courses, and visited eight of the houses he lived in – and even slept in his bedroom at Little Compton, though he did not appear in my dreams. Read thousands of letters and telegrams. I also tracked down people who knew him – former caddies, family members and the children of friend and associates, architects who worked with him – not easy, since Ross died in 1948.

2. What surprised you most about his life?

Well, I have to say I was disappointed there were no scandals or major fiascos in his life. That made it tougher to write about. I was amazed at his incessant train travel schedule; also at the amount of paperwork he and his small staff produced – literally a mountain of letters, design plans, telegrams. Too bad he had his secretary, Eric Nelson, burn so much of them upon his death burn, though I suspect it was the personal correspondence and business documents that were lost, not the design plans. I had also not realized before what a keen businessman he was and how actively he promoted his name and services.

3. Did you discover any hidden gems or lesser-known examples of his work?

Sure: Sakonnet GC in Rhode Island, a 5,891-yard, par-69 gem on the coast which Ross spent more time reworking than any other course he did outside of Pinehurst.

Teugega GC in Rome, N.Y., where Ross spent much of the summer of 1923 has some amazing features and loads of native fescues.

Hyde Park G&CC in Cincinnati, has some phenomenal ravines and swales that come into play.

I wouldn’t call White Bear Yacht Club in St. Paul, Minn., or Holston Hills, Knoxville, Tenn., hidden gems, but they sure are stunning and powerful for their ground contours.

Kebo Valley in Maine, Country Club of Columbus, Georgia, Misquamicut in Rhode Island all deserve more credit than they’ve gotten for their character.

I’ve been playing The Orchards in Mass. for 25 years and bringing people to see it, but perhaps that’s still a hidden gem.

My favorite ‘find,’ if that’s what you’d call it, is Wilmington Municipal in N.C., where guys pay $17 to play a pure Ross gem and don’t even have to wear a shirt.

4. How much time did he actually spend on his courses?

He saw most of them, even if only once. It varied. I tried to document which courses he visited and included a detailed chart in the book that indicates, among other things, the courses where evidence was available that he visited. Of the 399 courses for which he gets design or redesign credit, I figure he visited three-quarters of them, though in many cases it seems to have been only a single visit. But some he worked repeatedly, maybe about 40 of them. It’s strange; we criticize modern architects who do fly-by design, but Ross did his own version of mass production and it seems to have worked out well. That’s because he had great associates, Walter Hatch and J.B. McGovern, who worked with him for decades, and he had a sound way of routing courses.

5. What are the best-preserved examples of his work today?

Essex County Club, Salem CC, Whitinsville in Mass., and Wannamoisett CC in R.I.

Two well-preserved sleepers, in both cases at 36-hole clubs whose better-known ‘championship’ sibling courses have been much changed, are the North Course at Detroit GC and the West Course at Oak Hill CC, N.Y. Holston Hills is in great shape, though as much through restoration as preservation. Wilmington Municipal falls in the same category. Pinehurst No. 2 is authentic to Ross’ strategy, though the domed greens are a not at all characteristic of Ross and have become more severe than anything Ross ever built there.

Most of Ross’ famous layouts have been tinkered with and renovated, which is too bad. I think the greens at Brookside in Canton, Ohio are as pure a set of strong contours as I’ve ever seen. There are some amazing examples of intense restoration undoing years of tinkering. That list is what most encourages me about Ross’ work today: Lake Sunapee’s turnaround under Ron Forse’s tutelage is really impressive. I’ve also been struck by what Ron Prichard has done at The Orchards, Skokie CC in Ill., Longmeadow in Mass., and both Metacomet and Point Judith in R.I.

Essex County is a very well preserved Ross design.

6. What can modern architects learn from Ross’ work today?

A lot. They can learn how to route holes and put greens next to tees and how not to waste space or rely upon cart paths. They can learn to push putting surfaces to the edge of the fillpad and tip the edges of the greens to the outside so that the ball tumbles off. They can see the value of carry bunkers and diagonal hazards rather than placing everything at 270 yards from the back tees. They can learn to make approach areas inviting for the ground game. The biggest strategic thing they can learn is to stop putting all their features on the side and to start putting them down the middle so that players have to play around them.

7. Does it make sense today to engage in pure restoration, or are concessions to the modern game of length and aerial attack inevitable?

I spend the last third of my book on this topic. I know people think the game has changed a lot, and it has, but I’d always advise starting with the assumption that the course needs to be restored. I get sick when I meet up with designers whose first instinct is to alter or renovate under the presumption that the modern game and agronomy have bypassed classical design. The presumption has to be with restoration, and then maybe you relax a little from that.

A good rule of thumb is to expand greens, recapture bunkers, and if you’re going to add length, do it at the tee, not by moving bunkers or, god forbid, moving greens. Green speeds have gotten a little out of hand. They didn’t have Stimpmeters then, but Ross was designing for greens cut at 1/4 inch that were rolling at about 5-7 on today’s meter. Nowadays, they cut fairways that tight, and greens can be cut down to 1/10th of an inch. That worries me a lot, but in any case, I’d always advise restoring, then adding length on the long holes, not on the short holes.

8. What architects are presently doing the best (i.e. most faithful) restoration work on Ross courses at present?

Ron Prichard, Ron Forse, Tom Doak & Bruce Hepner are real good. There are others whose work I like a lot and many others whose work is scary. I’m always reluctant to pigeon hole architects – there’s too much of that at GCA, and I’d advise being more discriminating.

There are some architects who are interested in strengthening the identity of the course, which is fine. There are others who are good at recreating features but perhaps a little quick to update or to build lush, densely turfed features that are more polished and edged than Ross ever built. I’d be careful to avoid using bulldozers; restoration work needs to employ back hoes and hand work. I’d really avoid all of those architects who subscribe to modernization and who assume that old is dated and obsolete. It’s tough to make these distinctions, because some architects are great salesmen and can talk such a good act. I’d avoid people who don’t show reverence and respect for classical features.

The other thing is the choice of a builder/shaper. The best architects are worthless without a good shaper. The best restorationists spend a lot of time on site and pour their hearts and minds into it. I’ve been encouraged by the number of serious students of design who are interested in restoration with whom I’ve had great conversations about this. They were also helpful in the book. Not all of them have done a lot of – or even much – Ross restoration work, but their interest seems genuine – Todd Eckenrode, Kye Goalby, Keith Foster, Gil Hanse, Tim Liddy, David Savick, Brian Silva, Steve Smyers, Bobby Weed, Crenshaw and Coore, plus the ones I named above.

9. Two of his most interesting courses (the heavily bunkered Broadmoor and French Lick with its amazing green contours) are located in Indiana. Did he spend much or any time at either course? If he didn’t, who deserves the hands-on credit for them?

I’m not sure. I walked both of them without playing about seven years ago, but in winter and didn’t play. They are amazing, with Broadmoor having a wonderful, soft flow on pretty level ground. That was typical of Walter Hatch’s work, but I’m not sure. As I recall, they’ll need to remove a great number of trees there, but it’s all there. French Lick, by contrast, is built on hillier terrain and has some wild greens. That was certainly not Hatch or J.B. McGovern. I love the idea that it hosted the 1924 PGA. I can’t wait to see it again when we take our Golfweek Raters Cup there Sept. 20-22.

The 18th at French Lick highlights the rolling property.

10. What impresses you the most about the job that Ross did at Beverly CC, Chicago?

I wish there were design plans from Ross’ work there. And incidently, the ‘Architects of Golf’ book and other sources dating Ross’ work there to 1906 are wrong. It couldn’t have been before 1913, probably around 1916. I’m not even sure Ross’ work was completed, but he made great use of that ridge line and played up and off it to great effect. There’s a surprising amount of elevation change, at least 30 feet. It’s tough to get an interesting routing on a perfectly rectangular lot, and Ross did it with constantly changing directions at Beverly and no sense of parallel, back and forth.

The tee shot on the 2nd hole at Beverly CC drops some 40 feet to the fairway below.

11. What are Ross’s five most impressive sets of green complexes with which you are familiar?

That’s easy to answer:

- Brookside, Canton, Ohio

- Wannamoisett, R.I.

- Plainfield, N.J.

- Salem, Mass.

- Pinehurst No. 2, N.C.

The 13th at Salem CC is capped off by one of Ross's all-time best greens.

12. What are your thoughts on Metacomet CC in Rhode Island?

Great, unheralded Ross gem, squeezed into about 100 acres. Great collection of par-4s, and an amazing variety of par-3s, from a drop-shot short-iron at the downhill, 160-yard 7th hole to a driver at the 242-yard 12th hole. And that finishing run of 6 consecutive par-4s, each so different!

The par-5s (nos. 2 and 9) are too short. But what a job superintendent Paul Jamrog has done in restoring the classical look and feel through tree removal and fescues. Prichard’s plan has been great there. I just wish the membership were more appreciative of the gem they have.

13. Please list your all eclectic Ross 18, being faithful to the hole’s number.

Here goes:

- Whitinsville, Mass., par-5, 526-yards

- Sakonnet, R.I., par-3, 180-yards

- Lake Sunapee, N.H., par-4, 443-yards

- Seminole, Fla., par-4, 450-yards

- Longmeadow, Mass., par-4, 318-yards

- Plainfield, N.J., par-3, 141-yards

- Inverness, Ohio, par-4, 452-yards

- French Lick Springs, Ind., par-4, 377-yards

- Wilmington Municipal, N.C., par-5, 490-yards

- Wannamoisett, R.I., par-4, 416-yards

- Beverly, Ill., par-5, 594-yards

- Hyde Park, Ohio, par-3, 225-yards

- Franklin Hills, Mich., par-4, 298-yards

- Metacomet, R.I., par-4, 448 yards

- Holston Hills, Tenn., par-4, 380-yards

- Brookside, Ohio, par-4, 387-yards

- Pinehurst No. 2, N.C., par-3, 190-yards

- Essex County Club, Mass., par-4, 402-yards

The dramatic view from the 18th tee at Essex County.

Out: par-35 3,400-yards

In: par-35 3,340-yards

Total: par-71 6,750-yards

14. When Ross first arrived in Boston, Myopia Hunt and The Country Club were dominant courses. Is there any clear indication if these (or any other courses in the New England area) had a specific influence on Ross?

I don’t know. I never got a sense that Ross thought that way. He certainly was familiar with both courses, played them a lot, and knew people at those clubs. And Essex County certainly bears some resemblance to Myopia Hunt. Interestingly, Ross did a plan for a second 18-hole course at The Country Club in 1921 that would have required shortening the 15th and swinging it to the right. The plan was never adopted.

15. Scioto, Inverness, and Oak Hill are three famous examples of Ross courses that have been remodeled for the sake of hosting major events. Do you think other clubs have learned from the mistakes that these three clubs made?

No question in terms of Inverness and Oak Hill. They are widely regarded as how not to proceed in terms of club politics and changes getting out of hand and undoing what was there. Tom Fazio today agrees that the work he and his uncle, George, did there was a mistake. Not many architects will acknowledge that.

Scioto is more complicated. The changes were done in the early 1960s, but not to host a major. They kept their routing, and the only new green site was at the par-3 17th. But Dick Wilson, Robert von Hagge and Joe Lee raised the greens 2-3 feet and created that flashed up bunk er look on every hole, including half a dozen back bunkers. Unlike Oak Hill and Inverness, Scioto achieved a consistent look rather than having old and new holes side by side. But I wouldn’t be surprised to see Scioto address this in the near future.

16. What is the strength of Ross’s design at Holston Hills? How does it compare within the context of Ross’s other finest designs?

It’s very impressive. He had a construction team that was not afraid to open up slopes and create vertical drama on a diagonal line – perhaps it was the Mashburn Bros. out of North Carolina, who seem to have done some of Ross’ strongest work in the southeast/lower Midwest. There’s a boldness, an unpredictability there – love those cross mounds on the par-4 15th and hope superintendent Ryan Blair can carry through his restoration plan and reclaim the double fairway on that hole.

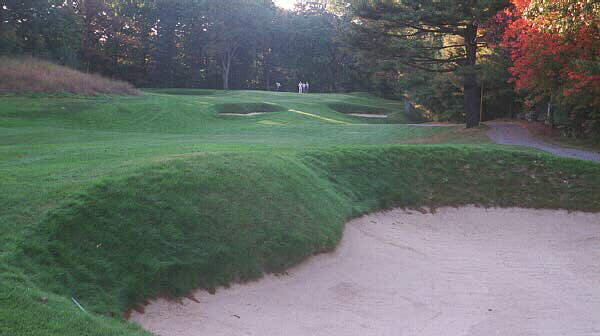

These unique cross mounds stretch across the entire 15th fairway at Holston Hills.

17. What impressed you about the design of Pine Needles during its staging of two U.S.Womens Opens?

The key to setting up Pine Needles is that you can calibrate the tee markers so that players are hitting into upslopes rather than carrying the crown of the fairways and running all the way downhill on their drives. That way, it plays so much longer than the yardage. You can still do that there for women pros, not for men (Pine Needles isn’t that long). The women were constantly facing uneven lies to greens that are extended out to the edge of the fill pads and rolled off into chipping areas and bunkers. And yet most of the greens are wide open up front. What a simple, elegant formula.

Many of the golfers in the 2001 U.S. Women's Open landed into the upslope on holes like the 2nd at Pine Needles. The resulting fairway wood to this green often met with a bogey.

18. Given your knowledge base on Ross, it seems logical that you could/would consult to clubs that have Ross courses. Do you have any plans to do so?

I’m a lecturer, an academic and a researcher by heart and by training, and so I’ve helped a few clubs look into their design history and identify strengths and weaknesses. But I’m not a designer, don’t carry any liability insurance, and have no plans to become one.

I find that much of the trouble clubs have is by way of in-house politics. There’s a great need for educating members, cultivating a sense of history and tradition, and having governance procedures that allow them to plan for the long run instead of zig-zagging year to year with new committee chairs. So I encourage clubs to develop and adhere to master plans and to hire architects to do that.

The End