Feature Interview No. III with Bradley S. Klein

November, 2006

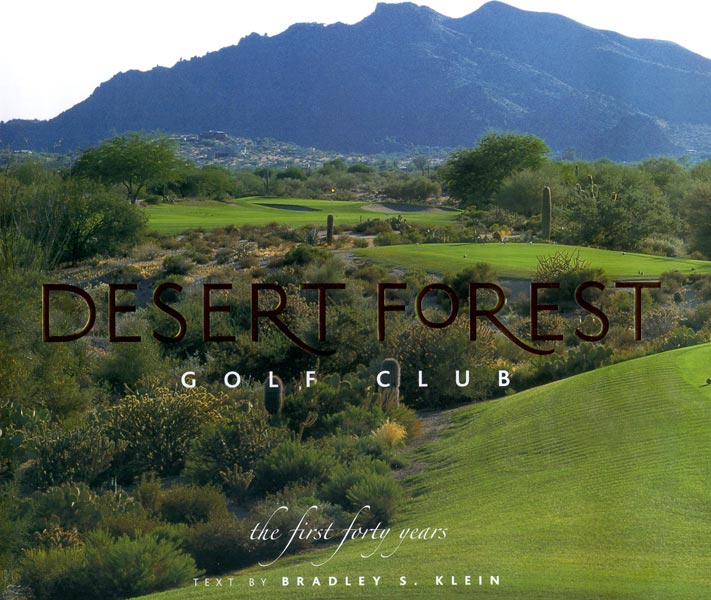

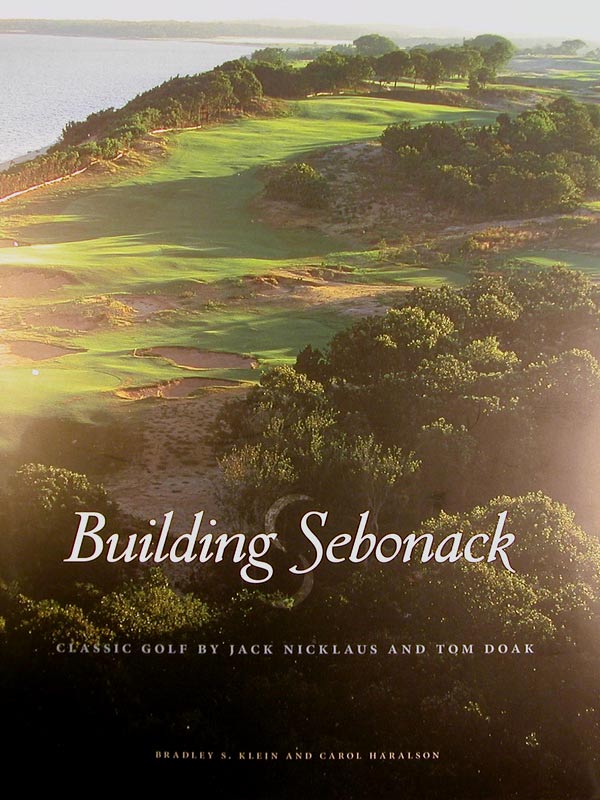

GolfClubAtlas.com’s first Feature Interview in July 1999 with Brad Klein revolved around his book Rough Meditations. Our second Feature Interview in July 2001 looked at Discovering Donald Ross. Since then, Brad has written, in order, Desert Forest Golf Club “ The First Forty Years; A Walk in the Park; Rough Meditations (expanded paperback edn.); and lately, Building Sebonack “ Classic Golf by Jack Nicklaus and Tom Doak.

1. Rough Meditations was first published in 1997 and is now a decade old. What have been the changes “ both good and bad “ that you’ve seen in the publishing of golf books during that time frame?

Golf publishing has changed steadily, with fewer people spending time reading. Magazine attention spans appear to be down as people get more accustomed to the look, feel and pace of Web-screen data. Book sales have been slowed. There are fewer publishers out there interested in serious golf books, fewer avid readers of golf books. The occasional big book will sell, like “The Greatest Game Ever Played.” But the overall audience is getting impatient with the written word.

The same goes for golf course architecture, which is a more avid, hard-core sector of the golf consumer market but reluctant to read seriously and to buy books. There’s still a dedicated group, but they are smaller than they think and reluctant to spend money on a well-produced book, which is discouraging, since production values in golf course architecture are crucial. You cannot get away with a cheaply produced book in course design and hope to sell it.

Production values and writing are still important. There’s a common myth that all architecture books sell the same number. That’s not the case at all. The informed golfing public isn’t foolish and won’t buy just anything. It has to be high quality, and those production values help distinguish poorly selling books from well-selling ones.

2. How does this version of Rough Meditations differ from the first edition? What drove you to revise it?

It’s simply about 20 percent longer, with about 30 pages of material from some recent essays and my “best and worst” selections. I have plenty of additional material, both published and unpublished, for another collection, and I’ll be working on it soon enough. But the hardcover edition sold out and the original publisher folded, so I thought it was simply time to do a paperback version of “Rough Meditations” with a new publisher, Wiley, and so I used the material as a modest incentive for anyone interested in buying it.

3. What other book(s) can we expect from you in the future?

I work in terms of five-year plans. The plan I am working on includes another collection of essays, as yet-unnamed, dealing with club management issues and how to mess up your golf course. I’m also now working on another high-end, private club history, like the Desert Forest and Sebonack books. I also have a design biography I’m starting, slowly, this one of a contemporary designer. And down the road there will finally be this kind of ambitious, more scholarly volume on the social history of golf course architecture. That might require another five-year plan to complete. I know there are some folks on GCA who like to talk through their work on the Website, even do some of the research there. I prefer working quietly, then sounding the drums when it’s out.

4. I have never been to Desert Forest Golf Club but in reading your club history, it appears that with each passing decade of expansion in Arizona, the course and club become all the more unique. Is that an accurate read?

That’s a fair read. It’s an unusual place “ no tennis courts, no spa, and no swimming pool or daycare center. Not even regular dinners. They do one club dinner a month, otherwise it’s a basic, 7,500 square foot clubhouse that barely manages to hand out lunch and drinks. It’s a golf club, for golfers, not for people who want to be seen or for celebrities who are pretending they don’t want to be seen. Everything else in the Scottsdale area is about glitz, money and show. Desert Forest is about golf.

5. Who was Robert ËœRed’ Lawrence and how did he develop such a keen sense for classic architectural features?

The real interest of the book is how unusual that course was, even for Red Lawrence. He lived 1893-1976, was originally a greenkeeper, a construction foreman who worked with William Flynn, then became a very mid-range designer in Florida and, after 1957, in the southwest. Lawrence would have simply drunk himself into oblivion except for two standout projects. The first was Desert Forest, 1962, in Carefree, Az.; the other, in 1966, was the University of New Mexico-Championship Course in Albuquerque. Both sets of greens are pretty interesting, but the convex fairways at Desert Forest are way more compelling.

I tried to explain how Desert Forest turned out so well. I think the key was the developers, two speculators, typecast right out of a Hollywood screenplay, named Tom Darlington and K.T. Palmer, who had no money to work with. Desert Forest was built on a shoestring. The shaper/builder, who died in a bar room brawl a few weeks after he was done with Desert Forest, got everything right. Maybe they were all drunk at the time. I guess they were taking after Macdonald, MacKenzie and Tillinghast.

6. Desert Forest has no fairway bunkering yet it calls for exact shot making off the tee. Please give a specific hole example as to how Red Lawrence accomplished this.

I always like to say that the course only has one big fairway bunkering “ the desert floor. The best example is the par-4 5th hole, 453-yards from the back tee, an “early dogleg” left, meaning the bulk of the turn comes on the near side of the tee shot landing area and so you’re always in danger of hitting it through the fairway on the right side. Bailout right and the fairway dead ends there’ leaving you in a pocket of safe turf that affords no way to reach the green. The landing area looks wide, about 40 yards across, but is turtle-backed and kicks out on both sides so that your effective landing area is less than half of that. The ideal tee shot is bold beyond imagination, over a clump of cacti on the inside left that looks impossible to try but, if played properly, leaves you with a clear if still long second shot in. The hole always drives me nuts. It’s one of those par-4s I try really hard to get in front in two on, and a bogey is a very good score.

7. Please describe your favorite hole at Desert Forest and what makes it so.

Without doubt, my favorite hole is the par-5 7th, 534-yards, with a true split fairway option of the tee, a barranca dividing the second shot landing area, and about five different ways to reach the hole. The risk line is way right, just bomb it over trees to a blind fairway, and hope you have a level lie. And the green defies imagination, always seems to repel the ball. Ever since they took out dozens of trees a few years ago and recaptured the playing width and options, the hole has represented to me that rarest of achievements with par-5s, a true double-fairway of options, and lots of strategy for high- and low-handicappers.

The one of a kind three shot 7th at Desert Forest

8. Desert Forest doesn’t overseed during the winter, yielding optimal playing conditions with the ball running out more than if it was overseeded. Given the extreme high regard that Desert Forest is held in the golf world, why don’t more Arizona courses follow their lead?

They now overseed. I fought it for a while, as did the leadership, but the demands and expectations of members and the need to attract new members in that market led them to cave in. To be fair, the winter conditions could get pretty messy, especially with any moisture, and the course got really beat up from the winter play, though it was fun playing that thing when it was crispy brown and pure links-like. But the members caved in. The new superintendent, Karl Olson, who was previously at National Golf Links of America for 17 years, is working really hard to ensure a light overseed and to preserve firm conditions. I go out there soon to play it overseeded for the first time.

9. Bill Coore prefers the challenge/professional opportunity to build courses on wildly different pieces of property; therefore, he stays fresh and avoids repetition. As an author, do you feel the same (i.e., was the opportunity to write the Sebonack book after Desert Forest especially pleasing, since the two are so disparate)?

The properties are totally different, as are the stories. Desert Forest was my “City Slicker” venture; an eastern kid, from New York City, now living in Connecticut, discovering the Wild West. Sebonack was a homecoming for me, though I grew up on the other end of Long Island. In both cases, I started in the beginning. With Desert Forest, that meant looking at the natural history of the desert, the Native American past, and then the odd saga of Arizona speculative land development. Sebonack started with glacier geology, then morphed into a more traditional tale of classic American golf design. You’re trying to discover a story and to tell an interesting tale. If you do your homework and look carefully, the stories are always very different. With Desert Forest I had to pry the story out of these characters; made me feel like I was doing “film noire,” somewhere this side of “Chinatown.” Sebonack didn’t have the mystery or intrigue, but it did have a lot of technical planning and site work that I could document.

10. Sebonack owner/developer Michael Pascucci and Jack Nicklaus are long time friends. How did Tom Doak get involved in Sebonack?

Pascucci decided he needed something different. The Nicklaus routing he got was done based upon some site constraints and expectations as to clubhouse location and entrance roads. Doak sent in a routing that overlapped somewhat with some of those holes but had a very different flow because he wasn’t worried about any of the roads and buildings. In fact, it was done entirely off a topo map and yet made very good use of the native dunes, and its rhythm took it to the water’s edge at the outset, the middle and the very end of the round. Pascucci was loyal to his longtime friend but he was also intrigued by Doak’s work. I admire him. It took courage for him to do it and it took courage for Nicklaus to agree, as well.

11. Both Nicklaus and Doak are strong willed personalities. What is your sense as to how they interacted during the design process? Given the different approach that the two design teams take when building a course, was it even harder for the respective design teams to interact?

They were professional about it. They both brought their strengths to the project and were backed by their respective teams. I think Nicklaus ended up learning a lot about building in what his associate, Jim Lipe, called “a sand-based medium.” Doak also learned about dealing with a little different clientele than he was used to, and he was forced to confront his own penchant for quirky ground game options. The differences all along were evident. Doak builds for ground-game shot makers, and his associates play golf that way. Nicklaus builds for power golfers used to hitting the balls miles in the air to a well-defined target, and his associates play golf that way, too. There was some awkwardness, but it gave way.

12. What role did Mark Hissey play throughout?

I never did get his “title” right, if he had one. He was project manager, baby sitter, the bill payer, the go-between, somewhere between nanny and executive director. Every successful project has to have someone like that. I can’t imagine how many cell phone calls, memos and meetings he had over the 4-5 years. But what was really unusual is the extent to which owner/developer Michael Pascucci ran the show. Hissey was a genius at mediating, at times going into Pascucci’s office and telling him what he needed to hear and what he needed to consider. Hissey was very good at knowing when to intervene and when to stay back.

13. What are the design strengths of Sebonack? Its weaknesses?

Sebonack’s design strength is the routing, the sense of a circular journey that starts by the water’s edge, returns to it mid-round and comes back at the end. You’re always turning, playing to the shoreline, away from it, and while you always have a sense of the other holes “ something I love, I just hate the notion of each hole in its isolated cocoon “ the “room” for each hole is very much of its own making and character.

The one weakness is that there’s a lot going on at and around the greens, sometimes too much for the surface area of the putting surfaces. I’m just not good enough of a vertical, power golfer to parachute shots into those targets, and I wish there were more room behind for softer recovery and more diverse options. You get a few too many of those downhill bunkers shots to greens that are a bit sloped and it gets very taxing.

14. What is your favorite hole at Sebonack and why?

No question: 15th hole, par-5, 616 yards from the back, though I play it at 580 or 536. It’s like a big, blow up version of the 4th hole at Bandon Dunes in how the water looms up behind the green, but only after you’ve turned the corner of the dogleg right. A massive diagonal bunker protects the inside of the dogleg. There’s plenty of room to play left, but I like challenging the left side of the bunker anyway. The second shot is sort of semi-blind, and while it’s easy to drift right here, that side leaves you no angle in to the green; you have to keep it left. I just like the space, the sense of apparent vastness yet with lines of play that you can think about. And the green sits like a stage in a proscenium arch, with bunkers all around and all sorts of slopes, and a handful of tall pines at the back of the stage, with the water visible through and under them.

15. Your 350-plus page Discovering Donald Ross established you as the preeminent authority on Ross and his designs. As you travel around visiting Ross courses, what are you seeing being done to them?

I’m seeing a lot of thoughtful clubs finally making amends for years of frightful neglect, or worse yet, for careless work by a generation of “landscape architects” who had turned their back on classic golf design. Every region had its local hacks, and now their work at these courses is being undone. The hard part of the process is the time it takes to get it right Usually, it’s not until the committee has messed up a project that they figured out what to do, and by that time it’s too late, the course is hacked around or the committeemen are out of power and a new group gets appointed and has to start over again.

The politics are often brutal. Most well-intentioned boards spend 90 percent of their time paralyzed and defensive in the face of criticism by 10 percent of the membership. It takes bold leadership, and it takes a membership that will allow itself to be led.

I also see a lot of really stupid projects, like $10 million clubhouse renovations preceding work on the golf course. Or members who are young and flush with money who think that their money will solve everything, and they are more impressed with “signature this” and “7,200-yard that” without looking into the substance of a classic design that, like all of Ross’ best work, defended par at the green and with ground contour. At least the word is now out on trees. They are finally coming down in droves. The only two classic courses I know that are still intent on planting trees are Augusta National and East Lake. Everyone else in the country has figured out that you need to simplify your trees, focus on mature specimens and not clutter the place with little dopey junk trees.

16. Besides writing on architecture and maintenance, you’ve also written widely on the golf market and the challenges facing private club, course owners and developers. What are three examples of different issues faced at facilities that you commonly see?

Clubhouse renovations are generally out of control. They all cost too much, overrun their budget, polarize the membership and generate no return on investment. If people want to spend available money from an accumulated capital fund, fine, but doing into debt or laying down an assessment for clubhouse work is really myopic.

There’s also way too much pressure on superintendents to produce one version of good maintenance (lush turf, fast greens, flawless bunkers, consistent rough). Greens are generally too fast for most members to play golf by the rules of golf “ or in a timely fashion. The result is that greens get stressed out, as do superintendents, and they are led to extract more from their golf course than the natural carrying capacity of the physical plant (the turfgrass) will reasonably allow. Maintenance expectations are far more extreme than they ought to be.

I’m seeing a big increase in the quality of club managers. The really well-run clubs vest their power there and don’t emphasize board governance as much; nor do they presume that an annually rotating president who gets to make all new appointments to various committees makes much sense. Along those lines, you are also seeing clubs where green chairmen get to stay for a few years and learn the ropes. That helps a lot, along with professional management at the top.

17. Golfweek’s annual rankings of modern and classic courses, which you run, have taken on a life of its own, generating much heated debate within the Discussion Group of GolfClubAtlas.com and other places. Are you pleased with its progress since its 1997 inception? Is there any aspect that you wish was different (though it probably never will be)?

I wish I had more staff support. I’m not just presiding over the ratings and the editorial output. I sometimes feel like I’m also baby-sitter to 400 raters. They are a great group, very enthusiastic, and they take their responsibilities seriously but I didn’t realize when I took this on “ who could? – that I’d be their travel agent, confessor, career consultant, and occasional editor, as well as mentor on golf course architecture. I’m glad to say that in many cases I’ve also become their friend. I also had no idea how big the whole program would become. We now do five 4-5 days meetings a year, with 50 raters in attendance at each one, and I put together the guest speakers as well as do a different PowerPoint presentation each time.

The main thing is we are taken seriously by the industry. Even though Golfweek has the smallest circulation of the major publications that are doing national course rankings, we seem to have found a place at the table for serious debate on the topic.

18. You’ve just landed a plum assignment — as a member of the consulting design team for the fourth course at Bandon Dunes resort. What can we expect of that course and what role will you play?

We can expect another very fine layout at Bandon, this one by Tom Doak and Jim Urbina. The fact that the two are getting co-equal billing is interesting, and it is appropriate, even overdue, given the significant role Urbina has played for over a decade in Doak’s design operation. This fourth site is entirely inland, unlike the original Bandon Dues course and its successor, Pacific Dunes. It also doesn’t have the transitional ground, long vistas and parkland areas of the third course at the resort, Bandon Trails. As for my role, it will be a very subordinate one, which is appropriate.

The fourth course at Bandon is going to be called Old Macdonald and will, according to owner/developer Mike Keiser, be an ode to the design genius of Charles Blair Macdonald, including versions of some of the famous holes that were seen at National Golf Links of America. It’s not a “best of Macdonald,” nor a recreation of NGLA or the long-lost Lido Club. But it will be an effort to create Macdonald’s style of strategy and design, as well as his panache and sense of the outrageous and bold.

To help the design team “ not that they need any help “ Keiser has formulated a little consulting group, including myself, Macdonald-Raynor expert/biographer George Bahto, and former longtime NGLA superintendent Karl Olson. We had a first meeting out at NGLA/Sebonack during Halloween “ good timing. All we did was walk around a lot, talk a lot, take notes, and come up with ideas. Half of design is talking and walking. The other half is problem solving. We talked about whether the course should be 6,600 yards or 7,200 yards from the back tees; whether it should have blind holes, and if so how many and what kind and with what severity; which holes from the Macdonald template we’d like to see in the routing; and whether the teeing grounds would be square or more naturalistic in shape. The main thing we decided is that we want to have fun doing it, that it ought to be a serious effort, and that the resulting course ought to be different and enjoyable to play while also being something of testament to classic course design

We also agreed that we’d spend most of our time exploring openly and thoughtfully these issues, and that instead of letting every detail out in blogs and Websites and promotional news items we’d try to focus on the overall style and approach of the golf course.

Much depends upon the routing and where certain design elements might best fit. I think the most important work the committee can do is to stand over the shoulders of Doak and Urbina and say things to them openly, critically, supportively, or even as skeptics and as ruthless critics, about whether the proposed plan is likely to work on that wind-blown site, whether the features are appropriate in scale “ which might actually mean whether they are as outrageous and as brash as they need to be while still working for golf. We’ll probably meet out on the site again in the spring and review the Doak-Urbina routing and see how the site works with that routing. All of us have been involved in dozens of these sort of things on one (informal) basis or another. Architects and planners call it “a charette,” which is a fancy French term for brainstorming about design. The term originally referred to an exercise that was rushed, heavily constrained and had to culminate in a design sketch. For now, we have the luxury of time, but eventually, Doak and Urbina will have to produce that sketch and then convert it into a golf course.

The End