Feature Interview with Stephen Goodwin

May 2006

Stephen Goodwin, the author of Dream Golf: The Making of Bandon Dunes, was a contributing editor at Golf Magazine from 1988 to 2001. He has written extensively about golf course design and golf history, and his first golf book was The Greatest Masters, a narrative of the legendary victory of Jack Nicklaus at the 1986 Masters. His articles and essays on golf have appeared in Links, The Met Golfer, Golf Connoisseur, The Washington Post, The United States Open Program, and The Masters Annual. In addition, Goodwin is the author of three acclaimed novels, the most recent of which is Breaking Her Fall. Among his awards are fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts and the Guggenheim Foundation, as well as magazine writing awards from the International Network of Golf and the Golf Writers Association of America.

1. What do you hope the reader will gain from reading Dream Golf:

The Making of BandonDunes? Two things. First, some inkling of the complexity of building a golf course. The story about Bandon Dunes that was repeated in most magazine accounts was inevitably a huge oversimplification. It went like this: Mike Keiser found great land in Oregon, cleared some gorse, hired a couple of architects who waved their arms, and volia! Bandon Dunes was born. The fact is that Bandon Dunes took years of planning and patience, and the place is the result of hundreds of decisions — any one of which could have led to a different result. And the second thing is that I wanted readers to see how the place is infused with the personality and character of the men who were most responsible for it. Several readers have told me that what they enjoyed most was learning about what Mike does when he’s not at Bandon, and about Howard McKee, Mike’s partner from the start and the one who succeeded in getting the permits and planned the resort.

2. Why were you selected to write this account?

In a way, I was like David Kidd — a dark horse, certainly not the obvious guy to write the book. There are many established golf writers who know more about architecture than I do. But I’d done some work for George Peper when he was editor of Golf Magazine, and when he became a consultant to Workman Publishing, he recommended me. Not because of the golf writing I had done for him — it was because he had just read a novel of mine. From the start, Peter Workman knew that he wanted this book to be about more than the specifics of golf design. He saw it as a quest, as the story of one man’s effort to fulfill a dream. In other words, he saw it as having the shape and dimensions of a novel.

3. Did you know Mike Keiser before you started work on the book?

No. We’d never met. Before I signed on to write the book, I wanted to make sure that I would have full editorial freedom and also that I would get along with Mike. We were going to have to spend a lot of time together, and I was afraid he might be a controlling type, someone who wanted his image burnished. And he had to trust me, too. So Peter Workman set up a round of golf to give us a chance to see how we got along. Right away I realized that Mike was great company — accessible, witty, and completely without pretense. Plus, we have the same tastes in golf course design, and play golf at about the same level of futility. We both like links golf, we like to walk, and we like to play fast.

4. How would you describe Mike’s taste in architecture?

He likes courses that have character and individuality. He has little fondness for most modern courses. He doesn’t like contrivance or artificiality. When he criticizes a course, one word comes up over and over — “boring.” He is a man who bores easily, and he can’t stand a course that plays the same way day after day. And he loves nature — his idea of great golf is that the golfer should have the experience of being at one with the land and the elements.

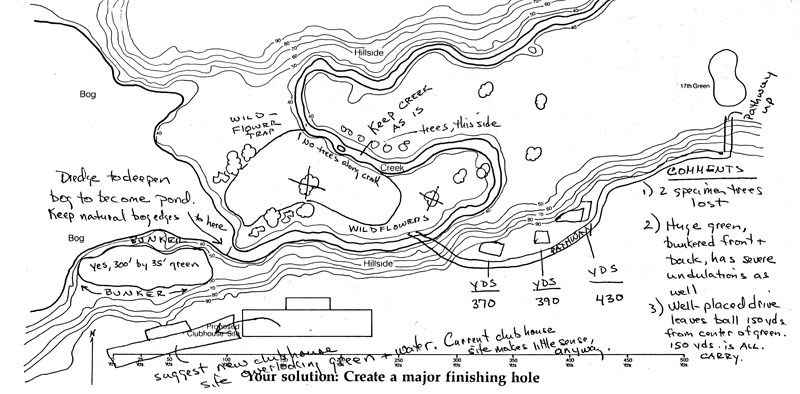

Mike Keiser’s hole entry in Golf Digest’s design contest.

5. What do you mean when you call Mike Keiser the ‘anti-tycoon’?

Mike has no need to blow his own horn or call attention to himself. The more I got to know him, the more I realized that he likes to operate in an old-fashioned, non-corporate way. He likes to look people in the eye, and he likes real give-and-take in discussion. His company, Recycled Paper Greetings, became a big company, but he ran it like a small business (this winter he sold a controlling interest, but he is still one of the key players in RPG). He has refused to take any title like president or CEO and once told a lawy

er that he was the “baron” of the company — a joke, but his point was that titles can create rifts and artificial distinctions. There’s nothing fake about Mike, and I know his modesty is real. When he saw the manuscript of the book, he wanted the story to start at Part II — leaving out the whole first part, which is about him.

6. What are some particularly favorite quotes that emerged from doing the book?

I used many of my favorite quotes to set the tone for each chapter of the book. Here are three favorites: David Kidd: “The way I’d put it is that both Tom and I built links courses, but Bandon is a modern links . . . Bandon looks forward, whereas Pacific looks back to the historic links and plays more as they do.” Bill Coore: “I can’t compete with nature, and it would only showcase my futility if I tried. So I try to cooperate.” Grant Rogers, Director of Instruction: “When people ask me if this is true links golf, I say the only difference between here and Scotland is we don’t have the skylarks.”

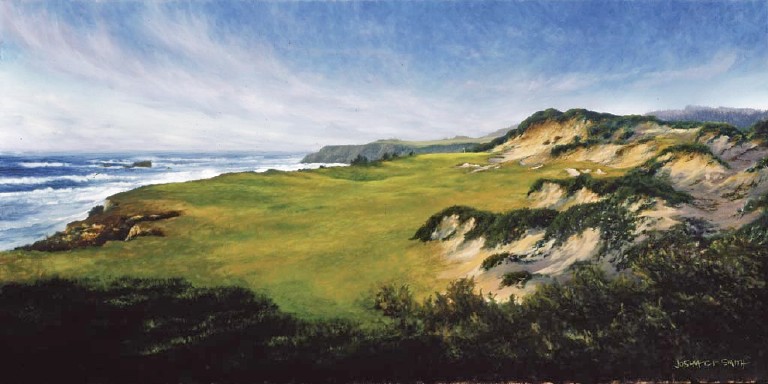

The 1st hole at Bandon Trails as captured by artist Josh Smith.

7. You quote Mike Keiser as saying, ‘George Crump is my hero.’

Please expand. Pine Valley, more than any other course, was Mike’s inspiration. He modeled the Dunes Club on what he had seen at Pine Valley. Beyond that, he admired Crump’s nerve and his willingness to do something completely original. Mike even likes to work the way that Crump did, very hands-on, asking lots of different people for their opinions.

8. During this same time period, Mike bought 60 wooded acres in New Buffalo, Michiganwithout the intention of turning it into a golf course.Please describe theevents that led Mike to consider and then proceed with building the nine hole Dunes Golf Club.

Mike bought the 60 acres as a “defensive purchase,” to protect the privacy of his summer home on Lake Michigan. At about the same time, he was looking at larger tracts of land in other parts of the country where he could build a golf course — but he was frustrated. When some adjacent property became available in New Buffalo, Mike bought it. He had already realized that his wooded dunes were similar in character to the land at Pine Valley, and he was by this time a full-blown armchair architect — so he decided to go for it, to build a 9-hole course that could capture the flavor of Pine Valley. But he didn’t do it alone. He hired Dick Nugent to do the design. He did a routing of his own, but Nugent told him, kindly, that his plan was a disaster. The Dunes Club was a great success, of course, and the lesson for Mike was that he didn’t want to be the architect — he wanted to be the producer, the impresario, the one who put al the different parts of the project together.

9. Some people erroneously think that it was a no brainer to proceed once the land was found that became Bandon Dunes. What were the negatives to proceeding?

First, it was a minor miracle to get the permits — that process took five years, and it wouldn’t have happened if Howard McKee hadn’t been on board. The previous owners had tried for years to get golf permits, and failed. There were big doubts about whether or not there was enough water on the site. The place was hours away from any “market.” The original setback requirements meant that the golf holes would have to be placed at a considerable distance from the edge of the cliffs. Even though Mike owned more than 1200 acres, the original site for the first course was constricted, with a much shorter exposure to the ocean. And once all these problems were solved, there was still the enormous challenge of designing a course worthy of the site. Anyone who is in doubt about the difficulties of designing on seaside terrain should take a look at the New Course at Ballybunion, designed by Robert Trent Jones. Great piece of land, but the course is damn near unplayable.

10. Mike became a founding member at Sand Hillsbefore seeing the property. He then made visits during its construction. What points did he learn from those visits in regards to the pending development of Bandon?

Mike loved Sand Hills and he became a big fan of Dick Youngscap, the owner, and of Bill Coore and Ben Crenshaw. Seeing what kind of course Youngscap had brought into existence in such an off-the-map location confirmed his belief in the Bandon site. Some golf people were telling him that Bandon would never work because it wasn’t near a “market,” but Sand Hills isn’t near a market, either. What mattered was the ground. And Mike says he would have hired Coore-Crenshaw — but he didn’t want to seem to be copying Youngscap. He did, by the way, offer Youngscap a job as construction manager at Bandon Dunes. He was impressed by how inexpensively Sand Hills had been built.

11. Of David Kidd’s original routing, how many holes bear a resemblance to the course of today?

Only one, the 17th. And the original name for the course was MacKenzie National. If that course had been built, and that name used, I doubt that anyone outside of Coos County would have heard of it.

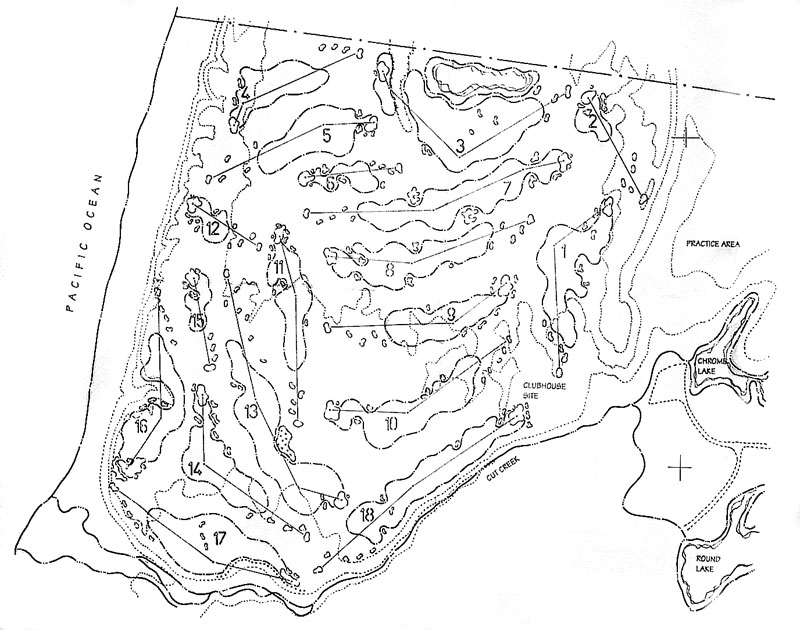

An initial Kidd routing, from 1994.

Another Kidd routing for the course that was tentatively going to called MacKenzie National. Though much of the second nine is as was built, the extra land to the north for the front nine had yet to be acquired as of this 1995 routing.

12. How did the final routing evolve?

You have to remember that David had spent less than a week on site when he did that original routing. The place was covered with impenetrable gorse, and he was working with lousy maps. Over the course of the next year, he spent months there, and a lot of the ground was cleared, and his routing was completely revised. Mike came out often with groups of friends — his “retail golfers,” people whom he thought of as representative of the kind of golfers he wanted to attract, the golfers who’d pay to play. They hit shots and talked about the routing. But it still wasn’t right. In Mike’s opinion, the front nine had a dull stretch of holes from No. 5 to No. 8, and David told him he didn’t see how he could do anything more. There just wasn’t any land. That’s when the serendipitous purchase of an adjoining parcel of land opened up new possibilities — and gave David a place to create the existing No. 5, 6, 7, and 8. And as we all know, that stretch of seaside holes on the front nine — 4, 5, and 6 — is one of the most exciting sequences in golf.

13. What role did Jim Kidd, David’s dad and the Director of Agronomy at Gleneagles, play in the whole process?

Jimmy Kidd and Mike just hit it off. Jimmy’s enthusiasm for the project, coming from someone who was a pillar of Scottish golf, did a lot to confirm Mike’s faith. Mike’s concern about American architects was that none of the famous ones knew how to build a real links course — but links golf was Jimmy’s birthright. And the very specific thing that Jimmy did was to figure out what kind of grass mix would work at Bandon. He started test plots to try out mixtures using fescue so that the first course would have true links turf. And the other Bandon courses use the same blend.

14. Every project has good and bad things happen along the way. What is an example ofa serendipitous event?

I mentioned one earlier — the purchase of 400 acres that gave David Kidd room for those great Cliffside holes. That same 400 acre parcel is now the site of Pacific Dunes, but there was still another piece of serendipity. At Pacific Dunes, Tom Doak needed more room to the north, and Mike had been able to purchase that land, too — and it is now the site of holes 13 and 14. Just think of it: Some of the best holes at Bandon Dunes, and all of Pacific Dunes, are located on land that Mike didn’t own when the project started.

15. What about a not so lucky break?

Probably the biggest disappointment was that no course could be built in the area of big dunes — the area where Bandon Trails No. 1 is located. This is the part of the property that fired the imagination of the first visitors, including Mike, and where he wanted to locate the first course. But there were environmental concerns about a rare plant called the silver phacelia (sounds like a venereal disease, said caretaker Shorty Dow). Later, Bill Coore and Ben Crenshaw tried hard to find enough room for 18 holes. But they couldn’t — so there are only three holes in those dunes. On a more prosaic level, a big headache and a major expense was drainage. Everyone expected the sandy soil to drain well naturally, but the water table was so high that extensive and deep drainage had to be installed.

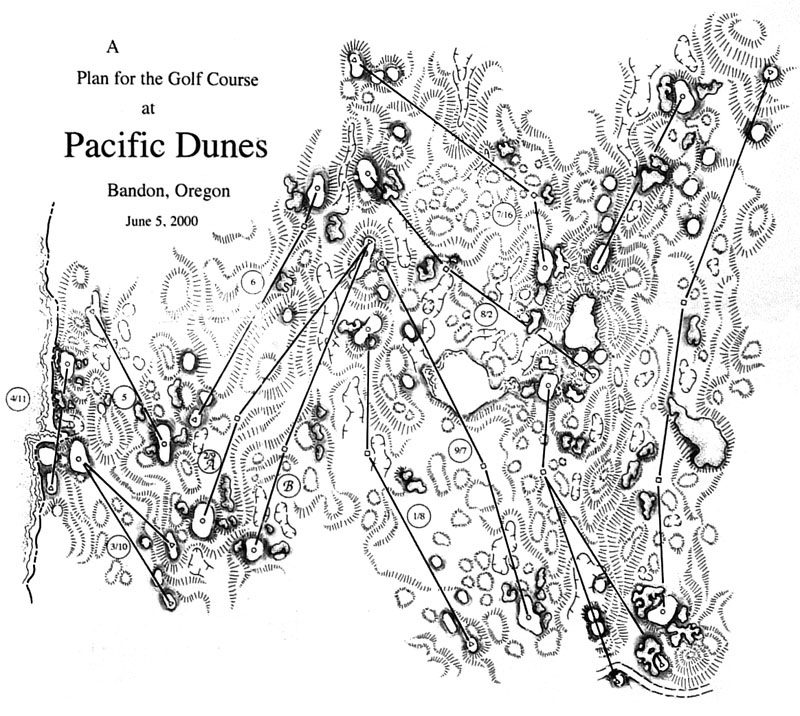

16. Pacific Dunes opened in 2001. How did it affect Tom Doak to be building the second course?

Tom wanted to build the first course. He visited the site in 1994 and lobbied hard to get the commission, but Mike thought he would be too controversial. He knew he wanted to work with Tom, though, and as it turned out, Tom got the best site — even David Kidd agreed that the topography of Pacific Dunes is more dramatic and varied than that of Bandon Dunes. Also, being the competitive guy that he is, and being such a contrarian, Tom worked very deliberately against the model of Bandon Dunes. Whatever David did, Tom was going to do differently. Having Bandon Dunes as a neighbor pushed him to define some of his ideas and give them bold expression. And finally, as Tom readily admits, it was probably an advantage that Mike had already been through the whole process with David, and willing to take even greater risks with the routing and design of the second course. Of course we can never know if Pacific Dunes would have been the same if it had been done first, but my guess is that it was a blessing to Tom that he was able to go second.

An early Pacific Dunes routing with many of the holes that eventually were built. The property where today’s 3rd, 4th, 12th, 13th, 14th and 15th holes are not included in this routing.

17. What was Jim Urbina’s role?

As Bill Coore said, “Without Jim Urbina, Tom’s wagon would have a wheel in the ditch right quick.” Jim managed all the administrative details of the project, and he was on site for something like 170 days, and Tom was only there for 50. The course was already built when I started to work on the book, so I didn’t get to see the design process, but even if I had I’m not sure that I would have been able to tell where Tom left off and Jim started. I’m not sure that they can always tell. And other Renaissance associates played key roles, too. I’ve talked to several of them, and to Tom and Jim at length, and I know that they all see Pacific as a collective achievement.

18. What is an example of how the courses continue to evolve?

The big blowouts on Pacific # 13 keep getting bigger — all the blowout bunkers require attention. Sometimes the wind scours out the bunkers and makes shapes that are downright weird. The bunker on the right front of Pacific # 18 is a source of constant discussion for Troy Russell, the chief superintendent, and the many others who have a say. On Bandon Dunes, the gorse was originally cleared almost completely — but there are many holes, like the 14th, where it is definitely back in play. And there have been many design changes at Bandon Dunes, like extending the left side of the fairway on the 16th so that an errant drive doesn’t result in a lost ball. One of the great things about Bandon is that the architects have all remained involved, and they work with the green keepers, like Troy or Ken Nice — who went from Pacific to Bandon Trails — who have grown up with these courses and are totally committed to keeping them in top shape.

The 13th at Pacific Dunes by artist Josh Smith.

19. Do you have a favorite course? Favorite holes?

Impossible question! If you listen to any group of golfers at Bandon, you realize that there’s no consensus about the best holes — there are so many good ones. I absolutely can’t choose favorites among the par 3’s since the whole collection, on all three courses, is so superb. But for sheer exhilaration, my list would have to include Bandon Trails #1, Bandon Dunes #4, and Pacific Dunes #2.

20. Will success spoil Bandon Dunes?

No, but I have to admit that I hear a lot of people talk about how the place has changed. It certainly has grown, and there are plans for a fourth course and perhaps more building. The original mystique was, here’s this remote, rugged, beautiful, unspoiled place with fantastic golf — but people who’ve been going for a while note that there are more creature comforts, and the price keeps rising. True Bandonistas, the people who think of a place as a club, don’t like to reminded that it is also a business.

21. What lessons did you take away from the experience of writing the book?

I was reminded that almost every great achievement, once somebody has pulled it off, looks simple and inevitable. But anyone who reads the book will be surprised, I think, at how many critical junctures there were, how many times Mike had to make the right call. There was nothing inevitable about it. Beyond that, and speaking very personally, I started working on the book at a time when I was feeling more than a little jaded about the game — but Bandon quickly reminded me of what I love about golf. It’s an inspiring place, and I got to know it better than I know my home course. There’s absolutely no place on earth where I’d rather play golf.

The 3rd at Bandon Trails by Josh Smith

The End

Postscript: for more information on art work by Josh Smith, please contact him at telephonenumber 925.639.8446 or via email at jcfsmith@aol.com.

The End