Roaring Gap Club

North Carolina, United States of America

Hundreds of millions of dollars have been spent building mountain courses since Roaring Gap opened in 1925. The question persists: is Donald Ross’s recently restored course the most fun of all?

By the 1920s, the Tufts family had done the hard part and turned the sandy scrubland around Pinehurst into a world renowned golf destination. People showed up October through May to enjoy golf under the fragrant pines and fast-draining soils. Yet, Leonard Tufts also watched as such folks retreated in the summer to Boston, New York, Pittsburgh and Chicago. The air conditioner had yet to be invented and the sun’s heat reflecting off the sand was more than most people cared to bear June through September. Working with a who’s who group of investors from Winston-Salem and Elkin, Tufts played a large role in the early development of Roaring Gap. He served as Roaring Gap’s first president and crucially solicited Donald Ross for the creation of its eighteen hole course.

The course opened in 1925 with Tufts proudly describing it as the ‘Aristocrat of Courses’ in the promotional material. For the next eight summers, much of the staff of Pinehurst’s famed Carolina Hotel journeyed 160 miles northwest to work at the 65 room Graystone Inn. The overlap of clientele and staff between the two places made for a wonderful atmosphere. Indeed, Tuft’s own summer residence was located near the entrance to the 1,200 acre parcel. Chris Buie, author of The Early Days of Pinehurst, notes ‘Some may wonder why a club tucked away in the mountains, hours from the Sandhills village, would be considered an integral part of the Pinehurst story. In addition to a superior Donald Ross course, Roaring Gap was managed by Tufts and fully staffed by personnel from Pinehurst. The same style and aesthetic was successfully transported up the road to Alleghany County. Although this made it “the summer Pinehurst”, it was, and remains, more than that. Roaring Gap Club happens to be located in one of the most stunning corners of the Carolinas. The phenomenal beauty of the area has always given the club an allure that rivals the best.’

Unfortunately, the Great Depression rudely inserted itself into the mix and forced Tufts not only to withdraw his expansion plans for 300 more rooms but to cease his involvement in 1933 for economic reasons. The founding families, like the Chathams of Elkin and the Reynolds, Hanes and Grays of Winston-Salem, weren’t profit motivated; their business interests lay elsewhere. Rather, their focus remained true to create a relaxing place for their friends to gather in an invigorating climate. Ross delivered the goods in typical Ross fashion by having the holes play relatively wide off the tee and defending par at the green. As this was meant to be a retreat, the course opened at under 6,200 yards and its elevation of 3,700 feet helped it play a touch shorter. His instructions to build a fun, relaxing course are – bizarrely – rarely issued today by owners/developers. Rather, they are more likely to bellow ‘build us a championship course that will be ranked in the Top 100.’ Such misguided wishes lead to dull 7,200 yard, par 72 courses ill-suited to both their property and potential members.

Meanwhile, Roaring Gap is absorbing to play, requiring an assortment of shots without being back-breaking. Ross expertly used the slope of the terrain both in the fairways and around the greens. A flatlander will struggle during his first few rounds as the course requires some getting to know. When you combine the uncertainty of the fairway lie with the soft shouldered, medium size 5,500 square feet greens, the golfer does not hit quite as many greens as he normally might expect on a courses that measures 6,455 yards.

A highlight is studying Ross’s wonderfully natural green sites: the horizon green at the fourth, the striking volcano green at the sixth, the seventh and eleventh on top of dramatic plateaus, the twelfth perfectly placed in a saddle, the sixteenth located in a dell, and the famed seventeenth green hanging on the edge of a bluff with seventy (!) mile views afforded to the Winston-Salem skyline on a clear day.

At the aptly named Do Drop sixth, ‘do’ hit the green or your ball will indeed ‘drop’ somewhere less advantageous!

Just appreciate how the challenge varies at the four holes above! The key at the sixth is to hit the knob-shaped green or your ball will drop down one of the slopes. At the eleventh, the risk is coming up short and rolling fifty yards back down the embankment. Find the green though and you’ll have a relatively flat putt. At the twelfth, many golfers intentionally come up short to diminish the aggravation caused by the green’s wicked four foot fall from back to front. At the penultimate hole, its infinity green tests depth perception. Ross’s disparate green sites ask the golfer sundry questions in the most natural, uncontrived manner possible, which is the very essence of golf course architecture of the highest order.

If the course is so architecturally engaging, why haven’t more golfers heard about it? The answer is two fold. First, it is a discreet membership, seeking neither attention nor course rankings. Second, the course has only in the past few years blossomed again into how Ross originally envisaged it. The usual had transpired over the six decades since Ross’s passing in 1948. Trees had encroached from the sides, robbing the course of his intended playing angles. Greens had shrunk from the edges of their fill pads, becoming both detached from the greenside bunkering and monotonously oval and bland. Additionally, the bunkers overall had lost their ability to intimidate and impress. While Ross’s bunkers had been cut into up-slopes and enjoyed a commanding presence in their day, the ones in 2002 were but two dimensional shadows of their former selves.

Led by Dunlop White, a long-time golf committee member, it all started to change in 2002. He contacted a budding restoration architect named Kris Spence, who also lived in the Winston-Salem/Greensboro area. Together, they accessed the historical information that Dunlop had assembled, much of it from the Tufts Archives in Pinehurst, including a full set of Ross hole drawings, green sketches and a routing plan. A vision appeared of a more dynamic, multi-faceted course than the one that existed.

Armed with incontrovertible photographs as well as Ross’s own notes, White and Spence campaigned for work to be done. The green committee and then club saw the wisdom in pursing a strict restoration and work commenced at a measured pace, first with some prudent tree removal that both helped the quality of the turf as well as opened up long views. Stands of native fescue grasses were also reclaimed throughout the course. America’s 2008 economic recession hindered progress but in October 2012, work to the holes began in earnest once the course closed for the season. As highlighted in the numerous photographs below, the project was a runaway success on all levels. As such, Roaring Gap is now the kind of course that the author cherishes the most: one that is fun to play on a frequent basis courtesy of its series of distinctive holes organically derived from the site’s one-off natural attributes.

Particular focus needs to be given to the green complexes and the work that was carried out to them from 2012 to 2014. They had shrunk from almost 100,000 square feet in 1930 to 72,000 square feet by 2000. The vast majority of the most exacting hole locations had disappeared too. There is no such thing as an interesting 6,400 yard course that features dull targets. Yet today, these green complexes create much of Roaring Gap’s enduring appeal. Ross aficionados will delight in seeing them, in part because they are some of the most genuine Ross greens in the country.

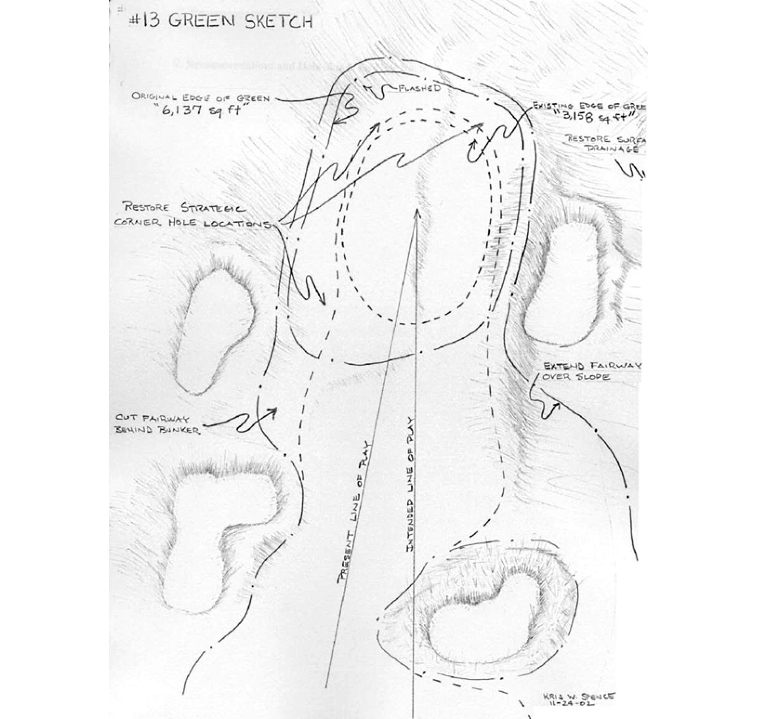

The importance of Roaring Gap’s green reclamation project can’t be overstated because it was the hole locations of exception that were recovered. Take the thirteenth as prime example. Its green almost doubled in size, picking up nearly 3,000 square feet of putting surface that allows for all the best perimeter hole locations to once again be utilized.

By doing soil probes, Spence determined that the putting surfaces had risen some 10-12 inches in the middle and 4-6 inches on many of the sides. This was enough to alter for the worse sight lines from the fairways as well as rendering the targets less interesting overall. Having developed over eight decades from topdressing, this organic matter was removed as part of the restoration. Now the greens bleed off on the rounded edges (examples include front left at the second and back at the fifth) while possessing more interior contour (examples include the spines once again found within the third and thirteenth greens that can be used to funnel balls toward certain side hole locations).

What’s fascinating is the process that was employed. White and Head Golf Professional Bill Glenn were adamant that the restored greens should not look like new greens. The members loved the evolution of their mottled greens and the mix of poa annua, bent and other mutations that had been carefully refined over the years to create lovely putting surfaces. Green Keeper Erik Guinther and Spence stripped back the green surfaces and stacked the sod to the side. They then pulled back the organic matter and cored out to the original green sizes, going down to Ross’s burnt cinders. Finally, they shaped the greens mix and replaced the sod. The rub is that often times they were ~35% short of sod because that’s how much the greens had shrunk over time. Therefore, they borrowed sod from the second green to complete the first green, and so on. By the time they had done the sixth green, all the sod on the first nine greens had been utilized. For the last three greens on the front, they sourced the sod from the 20,000 square foot sod farm they germinated from green plugs near the maintenance facility. The sod from there was of the same composition and enjoyed the same appearance and texture albeit being younger. Importantly, none of the younger grass from the farm was ever mixed with the older grasses on the same green. This process played out over three autumns until the club ended up with eighteen newly restored, seasoned greens.

As seen from back right, the tenth green lays peacefully on the ground yet is full of mischief with its high front left and back corners. Modern architects too often build more compartmentalized greens, which are far more garish in comparison to Ross’s nuanced handiwork.

Taken as a set, these greens offer great insight into Donald Ross the architect. As we see below, the variety found within them is such as to preclude them from being stereotyped – a most laudable quality that has gone wanting in the evolutionary process of some of Ross’s more noted designs. Indeed, the author scratches his head in attempting to come up with just three Ross courses that are as authentic to Ross’s interpretation of good golf as Roaring Gap.

Holes to Note

Fourth hole, 385 yards, Graystone; For all the world, this uphill hole feels like a Home hole as it is perfectly aligned with the majestic, architecturally significant Graystone Inn in the background. Indeed, for the first several years, this was the Home hole. Tufts realized that the members and their guests arrived at the club in the afternoon and relished the prospect of late day golf. Today’s intimate golf shop 3/4 of a mile away had yet to be built. Tufts consulted with Ross, who acquiesced for the fifth hole to serve as the first on a temporary basis. So it went with the fourth becoming the eighteenth. This arrangement lasted for fifteen years, from 1925 to 1939.

Though it should go without saying, wherever there is a Donald Ross uphill green, a premium is gained by staying below the day’s hole location.

The picture perfect clubhouse at Roaring Gap is found between today’s fourth green and fifth tee. Its exterior has been faultlessly preserved for nine decades.

Fifth hole, 395 yards, Blue Ridge; Given Graystone’s splendid location along the hillcrest, no surprise to find that this hole (and the next several) falls downhill. While it may be easy to imagine this as an opener with its generous landing area, the green itself is quite wicked, having been a chief beneficiary of Spence’s recovery work. Left and rear hole locations have been restored. Indeed, the back third of the green follows the general slope of the land from the tee (i.e. the green falls away from the golfer) and the closely mown banks work to sweep the overzealous approach shot well away from the putting surface. As well as any hole here, the fifth epitomizes the concept of room off the tee while challenging the golfer at the green. Given that the green is open in front, it’s also a prime example of how a grandfather, his son, and grandson can all enjoy playing the same hole. A high, soft approach with plenty of grab as executable by a strong player might be ideal for certain vexing perimeter hole locations but the wily veteran can also access them with a finely judged running approach shot that takes into account the general right to left tilt of the green and its surrounds. One envisages Ross himself playing it just that way, cagily making sure he carried his own bunker some thirty yards short left of the putting surface and then watching as his ball scampers onto the open green.

As seen from short right, the fifth green is open in front. See the low mounds around the perimeter of the green? In 2002, they were five paces removed from the shrunken putting surface. Ross’s features are again part of the putting surface where they influence play.

A common sight: the right to left sloping fairway produces too much draw and a player’s approach hits the left edge of the green, only to release down the tightly mown bank.

Sixth hole, 145 yards, Do Drop; Unlike C.B. Macdonald and Seth Raynor, Donald Ross didn’t believe in template holes. One imagines him thinking, Every site is unique and so too should be their holes! However, one particular type hole did seem to capture his fancy and that was a one shotter to a knob green falling away on all sides. Some dub it a volcano green and examples are found in Pennsylvania, upstate New York, New Hampshire, Florida and elsewhere in North Carolina. Even for Ross who designed well over one thousand one shot holes over five decades, Roaring Gap’s volcano green complex must rank near the top. As at Rye, the second shot is often the more important one! While its modest yardage might seem manageable to the card and pencil sort, the sixth features a domed green that measures 3,950 square feet – and plays much smaller. Akin to some of the most wicked greens such as the fifth and sixth at Ross’s beloved Pinehurst No. 2, only ~40% of the green is suitable for hole locations. The front third of the putting surface is one long, slow, agonizing false front. Watching from the tee as a ball lands six paces onto the putting surface before beginning a trickling retreat fourteen paces off makes for one of those indelible moments that Ross could create – and that many modern architects don’t. In the 2008 Carolina’s Senior Amateur, not confined by the one ball rule, contestants switched to the low spinning Pinnacle golf ball on this tee so that the first (and second) bounce would be forward on this putting surface.

Do Drop is one of the state’s most iconic holes. Its green size was expanded 19% during the reclamation project, allowing balls to depart the green at a greater velocity, ending up in more places. A wider range of recovery shots is required, which highlights an indisputable but often overlooked fact: larger greens actually make certain holes more challenging.

As seen from the left, Ross draped the putting surface with both a false front and false back. The more you play it, the tinier the effective hitting area in the middle of the green becomes!

This gentleman’s tee ball was rudely kicked to the side and down, leaving this problematic recovery.

Seventh hole, 520 yards, Hillandale; This is the first of two bunkerless three shotters. Let’s face it: the notion of sandy hazards (a.k.a. bunkers) is a bit out of place on top of a mountain. Ross only employed forty-six bunkers at Roaring Gap, instead using the natural attributes (pronounced landforms, creeks) to provide the challenge. To that point, Ross located this fairway between a hill right and creek left. Each shot becomes progressively more challenging as one tacks his/her way down the hole, thus fulfilling the definition of a classic par 5. Assuming that the golfer can avoid both obstacles on his first two shots, he is left with a pitch to an elevated plateau green tilted markedly from back to front and right to left. The tension of carrying the fifteen foot embankment on which the green is perched while staying below the hole has never wavered in its appeal. Indeed, with today’s swift green speeds provided by the native poa annua and bent mix, a canted green like the seventh prays more on the nerves today than it did in Ross’s day when the greens ran 25% slower.

The creek left and sloping land right provide plenty of natural challenge. No need to clutter the hole with bunkers.

Eighth hole, 400 yards, Meadow Brook; Roaring Gap is a wonderful walking course, with no real hilliness to speak of save for the stretch from the elevated eighth tee to the twelfth green. While the golfer might not take kindly to the uphill walk to the tee here, all is forgiven when he turns around and sees the sweep of the broad fairway some sixty feet below, as captured by the lead photograph of this course profile. Done too often and the course becomes unwalkable but this joins the tenth as the two great drops tee to green on the course. They are timely reminders that you are indeed enjoying mountain golf. After the round, you might well scratch your head wondering when Ross ever took you uphill the same amount but such is the skill of a master architect!

Tenth hole, 370 yards, Spring Branch; Across the road from the golf shop, Ross intended this pleasant downhiller to be the first hole yet, it never once served that purpose! Once the golf shop opened in 1939, the decision was made that Ross’s tenth (today’s first) would be the opener. Why so, one wonders? Well, today’s first tee is both closer to the golf shop and the practice area. More importantly, one imagines that the singular allure of ending with the glorious valley views afforded from today’s penultimate green (Ross’s eighth) was an overriding consideration. Also, Ross’s own Home hole (today’s 300 yard ninth) wasn’t as inspired a conclusion as the indomitable 235 yarder that is today’s finisher.

The obvious task at hand on the approach to the 10th is to avoid the deep greenside bunker. The less obvious challenge is to make sure one’s ball stays below the day’s hole location. The green follows the flow of the land, making it extremely quick from back to front.

Eleventh hole, 515 yards, Eleventh Heaven; Roaring Gap opened in the age of hickory golf and the seventh and eleventh would have been largely unreachable in two blows back in the day. Roll the clock forward to 460cc drivers and steel fiber shafts and the accomplished golfer can carry a draw far enough to get additional scoot to reach either green in two. Plenty of other sub – 6,500 yard courses might be overwhelmed by the relentless onslaught of technology but not Roaring Gap: its green complexes are too well conceived. Both at the seventh and again here, the plateau green with its steep embankment in front is a trying target to hit from 220 plus yards away. In the case of the eleventh, its embankment is double in size of the seventh’s and shots just short roll back a good 50 yards, leaving the dreaded half wedge shot. Similar to Pinehurst, having the ball return to your feet after an inadequate wedge shot is disgruntling, to say the least. As well or better than any architect before or after, Ross’s fine targets stand the test of time.

Twelfth hole, 370 yards, Silver Pines; What a beast this hole would have been in the age of hickories! Not only is the drive a forced carry over broken ground but the hill’s shoulder on the far side would have stunted forward progress. Most golfers would have been left with a mashie (5 iron) or more into the course’s most viciously sloped green, featuring nearly four feet of fall from back to front. Though the green may look innocuous as it lays peacefully in its own saddle, any ball fractionally beyond the hole location is a genuine struggle to get down in two shots. Many a member advises of the merit of an uphill chip from just shy of the green versus a sidewinding first putt. If Sir Isaac Newton had been a golfer, he would counsel to use gravity as your friend and not fight it.

The most intimidating tee shot comes at the twelfth. The hill’s pronounced shoulder shunts tee balls left to the point where the overhanging branches from the massive oaks become a consideration.

This side view across the twelfth (and up toward the one shot thirteenth) only hints at the green’s terror.

Fourteenth hole, 385 yards, Miss Alice; Aerials of the property from the 1920s show that Ross carved the first nine through a forest. That’s typical of most mountain designs but what is surprising to discover is that the middle section of the second nine was much more open, almost a meadow in fact. The golfer senses that here but it isn’t until he crests a ridge some 140 yards beyond the tee that its full expanse manifests itself. One of the most captivating spots on the course, the fourteenth green lies ahead over a creek at the base of a hill. To the left, the full effect of the downhill tenth is enjoyed as is Ross’s clever use of the twisting topography at the eleventh. To the right, the massive 120 yard wide shared fairway of the next two holes is evident.

Ever faithful to Ross’s hole diagrams, Spence restored this ‘top shot’ bunker that Ross had carved into the crest of the hill some 140 yards from the tee. Once beyond it, the fairway tumbles down a steep valley hill.

Fifteenth hole, 410 yards, Straight-A-Way; To gain a sense of how much was accomplished from the Spence restoration, look no further than this hole where four crucial events dovetailed together. First, there was an additional fifty yards behind Ross’s tee that allowed this hole to be stretched to 410 yards, making it the longest two shotter on the course. Second, Spence followed the old aerials, removed a row of eleven pine trees that had been mistakenly planted to divide the fifteenth and sixteenth, and reclaimed the shared fairway. All the bunkers on the hole regained a three dimensional quality as depth was returned to them, which additionally turned them back into true hazards that need to be avoided. Finally, the green was expanded a whooping 55% with numerous hole locations recovered front left, front right, and along the back; it’s now the biggest green on the course and perfectly punctuates the longest two shotter. Many good players consider this their favorite hole on the course, both because of its aesthetic appeal as well as its stout golf requirements. When the author originally played it in 2001, the 360 yard hole from the lower tee to a small oval green generated little affection. No more!

Sixteenth hole, 540 yards, Dolls House; Living in Pinehurst/Southern Pines, the author is both perplexed and disappointed that the closest modified punchbowl green by Ross is three hours away in the mountains. After all, sand soil is typically what is required for such a green complex to drain properly. Nonetheless, Ross’s imaginative green placement in a natural dell area makes the sixteenth a standout. Golfers going for the green in two – or those who get in trouble along the way – face a blind shot. As with the fifth green, the golfer must use the surrounding slopes to work the ball in toward the hole. Learning how to judge such approaches is something that the golfer never tires of trying. Architect and course critic Tom Doak was so captivated by this feature and the other par fives that he listed Roaring Gap as possessing one of the world’s best collections of par 5 holes in his 1994 Confidential Guide, joining such household name courses as Pebble Beach and Augusta National. The severity of the side-sloping green site – and the options available to a creative shot maker – reminds the author of one of his favorite greens in the world: the fifth at Merion.

… the sunken green reveal itself. From the spot of this photograph, the author witnessed perfection: a member punched a low rolling draw with a hooded seven iron at the large oak tree behind the green. The ball scooted onto the green on line with the smaller tree beside it. As the ball slowed, it dutifully started to break left … and continued doing so. By the end, the ball was traveling perpendicular to the line of the shot and finished a few feet away.

Seventeenth hole, 345 yards, Valley View; A short-ish length two shotter, this hole has great strategic value and yet is the sort of hole rarely built these days. The infatuation seems to center around drivable par fours twenty to fifty yards shorter versus ones like this that is more of a two shot chess match between architect and player. Pity. In this case, two fairway bunkers and out of bounds right and a serpentine greenside bunker left that wraps in front of the green create the enduring playing angles. The ideal tee shot flirts with the trouble down the right in order to give the golfer a clean look down the long but narrow green. A ‘safe’ tee shot to the left leaves a trickier approach over the serpentine bunker on an oblique angle to the green.

An impeccably conceived golf hole, where the playing strategy is a near match for the hole’s natural splendor.

The pay-off for flirting with the two fairway bunkers is this uninterrupted view of the putting surface.

As the golfer shies left off the tee, his approach shot becomes progressively more complicated thanks in large part …

Only here did Ross employ such bold greenside mounding. No written word exists as to why but a popular belief is he did so to mimic the distant mountains.

Eighteenth hole, 235 yard, Hill Top; Not to belabor the point, but Ross never intended this long one shotter to be the Home hole. It was always his ninth. Regardless, like Brora Golf Club in Scotland north of his Scottish home of Dornoch, a testing one shotter makes for a fitting conclusion. This one is an engaging 1/2 par hole with most pars secured via a one putt and avoiding the attractively deep bunkers. Ending with such a taxing shot is but one of the reasons why many folks don’t realize that they just concluded a round on a sub 6,500 yard course. It’s a very neat – though hard to accomplish – trick that Ross pulled off: make the design so diverse and compelling that length becomes largely immaterial.

Roaring Gap requires all sorts of shots, including a big thump with a three wood to reach the Home green. The far upslope provides the perfect canvas for some of the deepest bunkers on the course.

The better the information going into a restoration, the better the outcome. White made sure that Spence had every scrap of information possible (black and white photos, Ross’s hole diagrams and notes). As example, this photograph was taken in 1926 (well prior to the golf shop being constructed). The accuracy of Spence’s work speaks for itself. The measured pace of the twelve year restoration process allowed all pertinent information to be discovered and analyzed.

This side left view captures Ross’s beautiful contours that Spence returned to the interior of the green. Before the restoration, the green was oval, puffed up in the middle and featureless.

The hallmark of all great courses is captured simply: how strong is the desire to play it again? After holing out on eighteen, this view back across the last two holes tempts one to return immediately to the first tee, which happily is a scant 40 yards away.

At 6,455 yards in the thinner mountain air, Roaring Gap might not be ‘great’ by modern definitions but that only signifies that such definitions are in dire need of being revisited. Nothing more asinine than a course that is ill suited for its membership. Neither restoration chair Dunlop White, a gifted player and six time club champion at Roaring Gap, nor Kris Spence saw need for much additional length. Yes, back tees were found for holes eight and fifteen to give the course two par fours at or over 400 yards. Otherwise, only another 100 yards was added over the other sixteen holes. Ross’s greenside slopes and Guinther’s ability to produce fiery playing surfaces in the mountain clime sufficiently tax the talented club golfer. White notes, “Five straight club championships I was more over par at Roaring Gap than I was at Old Town.” So much for those who wish to dismiss Roaring Gap as a chip and putt. More length would have been meaningless to 90% + of the members; the irony is that few other clubs take such an intelligent stand and resist adding pointless length. Back in the days of hickory golf, Roaring Gap was lauded as the finest mountain golf course in the country; that sentiment contains a much greater degree of accuracy than some realize today.

Most people arrive at Roaring Gap either from the south or east. A winding 4.8 mile drive known locally as the Blue Ridge Rampart transports the person from the North Carolina foothills three thousand feet up to the entrance of Roaring Gap, which is unmarked but for a low key wooden sign well inside the turn. Once on the property, decompression begins and there is no compelling reason to leave. The club’s diverse offerings include clay tennis courts, a beach club, stables, and a nondenominational church.

All in all, Roaring Gap is just what the founders envisaged – an engaging place for all to enjoy and escape the summer heat. Its golf course once again epitomizes the joys that can be derived from mountain golf. Ross’s superlative routing capitalized on the varied natural features and stands in stark contrast to many modern Carolina mountain courses where the land was tortured during the expensive course construction. Too bad more owners don’t allow today’s architects to worry less about distance and difficulty and focus more on intricacies and charm. No wonder golf is in the mess that it’s in, not that the perfectly contented members at Roaring Gap would know or care as they happily go about playing a sport that is actually quite fun.

The End

![The Park, West Palm (Lit 9) [2023]](https://golfclubatlas.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/IMG_7092-2-scaled-500x383.jpg)