Pebble Beach Golf Links

California, United States of America

Few places conjure powerful images and thoughts to golfers and non-golfers alike. Pebble Beach is one of those magical spots. So much has been written about the place and so many comments have been rendered, it’s almost cliche. We add these few thoughts on its evolution:

- The course opened for play in 1919 measuring a bit over 6,000 yards. Jack Neville and Douglas Grant’s routing provides the bones of today’s course and they deserve accolades for the imaginative manner in which the holes move along and away from the storied shoreline.

- H. Chandler Egan, however, is the man most responsible for how the course plays today. In 1928, he replaced sixteen of the eighteen greens (leaving Alister MacKenzie’s eighth and thirteenth greens untouched), completely reconfigured the bunkering schemes and made the course into a strategic marvel. Black and white photographs from the day highlight incredibly artistic faux sand dunes, though they were surely maintenance nightmares.

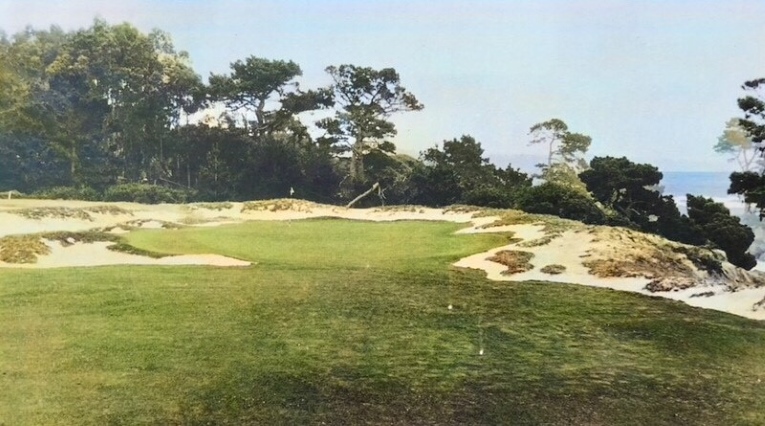

Egan’s dune handiwork is evident around the 4th green. It is every bit as handsome as it would be difficult to maintain in such a blustery environment.

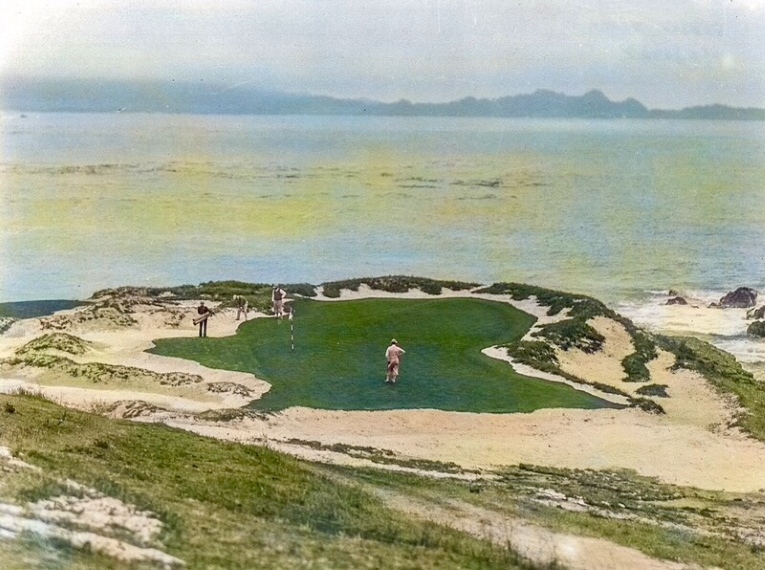

Same for 7th. Bunker depth is required to keep the sand in place on the 7th’s exposed point; to imagine anything else is wistful thinking. On the positive side, Egan’s hazards were connected to his putting surfaces. Too many of today’s greens have an awkward 3 to 9 foot band of rough between the ‘greenside’ bunkers and the putting surfaces. Pity more short grass isn’t incorporated around the greens for variety sake.

- Should Egan’s redo be viewed as one of the singular moments in the development of American architecture even though it didn’t stand the test of time? Yes, emphatically so. Look no farther than the third hole for a shining example of how Egan oriented a green to be approached from a certain side of the fairway and how that proper side was protected by an interesting feature (a ravine in this case).

- Poorly considered bunkers have been added in modern times to the outside of the third and along the right of the thirteenth fairway. They should be removed as they fly in the face of Egan’s ‘less is more’ principal. The golfer has already suitably penalized himself by being out of position. Besides, approaching those greens from the rough is more problematic than from the sand for the good player.

- Broadly speaking, California has been a poor custodian to its Golden Age gems, despite notable exceptions at Los Angeles Country Club, the California Golf Club of San Francisco and the Valley Club of Montecito. One can only hope that Pebble Beach – the very definition of a national treasure – will one day emulate a similar, detail-oriented restoration. In particular, the greens at Pebble are surrounded by thick-rough more than bunkers and that is not what Egan intended.

- Ironically, the greens have gained fame as being the smallest and most fiercely pitched greens of any U.S. Open course. The effective playing surface of Pinehurst No. 2’s greens might be similar but the average green size at Pebble Beach is a mere 3,500 square feet, a whopping 44% less than Pinehurst’s No. 2’s average 6,200 square feet. Hitting the middle of each green at both historic resort courses leaves a manageable length birdie putt but in the case of Pebble Beach, this was not Egan’s design thesis.

- On the bright side, more so than any course to host a major in North America, a good competition at Pebble Beach is not reliant on green speed. Rough will always be suitably thick in the moist coastal climate. Throw in small targets and a breeze and the hosting organization has little to do to get the course set-up right.

The 13th is one of many fine inland holes, made so by how Egan’s sprawling sandscape worked in concert with MacKenzie’s severely canted, right to left green.

- Britain’s Herbert Fowler deserves credit for the tee location jutting into the ocean as well as the clever placement of the Home green. In 1921 he pushed it back some 170 yards around a bend in the cliff line to transform Neville and Douglas’s tepid 325 yard two-shotter into one of the game’s iconic par 5s. Fowler’s crescent shaped fairway is full of interesting playing options and with today’s technology, golfers have to commit to a bolder line from the tee to hold the fairway with a driver.

- Some people say the Home hole is overrated – they grouse it is ‘a three wood, lay-up, wedge.’ Talk about jaded! Technology has actually made the eighteenth more fascinating as strong players go for it in two with ever increasing frequency. Similar to the ‘coming home’ sensation at St. Andrews, the walk is made all the more uplifting by the delightful prospect of a potential birdie. Pity, so many modern architects haven’t followed Fowler’s lead, instead opting to end their designs with some sort of grueling two-shotter that browbeats players into submission.

- Some contend that the long fairway bunker along the seawall on eighteen is awkward and should be eliminated. Let the ocean defend the preferable left side versus having a hazard beside a hazard, they espouse. Truth be told, the spray from the salt-water crashing into the rocks is such that it is impossible to present healthy turf along that section and the long bunker is a neat solution to the dilemma posed by Mother Nature.

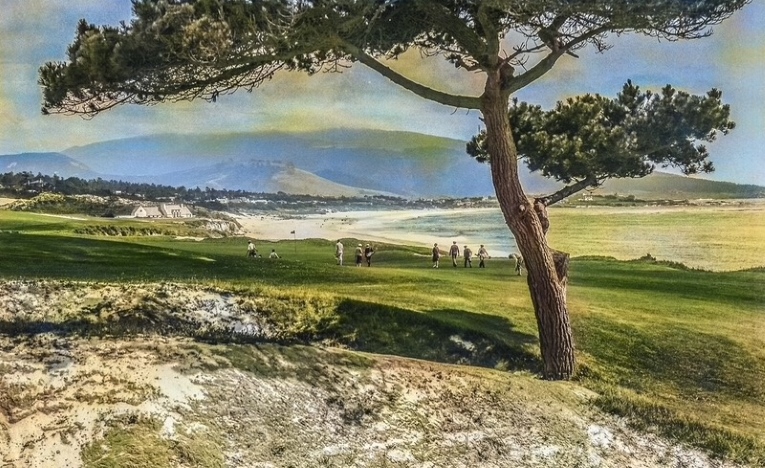

This postcard from the 1930s was before the building boom around the Hotel del Monte. Can you imagine playing there then?! First time visitors these days are often surprised by the level of non-golf activity swirling around holes 1, 2, 3, 4, 15, 16, 17 and 18.

- No one would design Pebble Beach the same way today. No telling how a modern architect would handle the section of property that houses the sixth, seventh and eighth. Modern viewpoints might condemn those holes as respectively being too uphill, too short and too blind – and that would be tragic.

- Egan did all he could to lend the seventeenth playing interest with his creatively angled hourglass green. Still, it is puzzling how people consider this a ‘great’ hole, even after the green was mercifully expanded by 40% in 2015 to 5,000 square feet. Alas, the hole occupies dead flat land and left hole locations remain too much of a” hit and hope.” Sadly, the other one shotter on the second nine is even more poorly presented. Like the penultimate hole, the twelfth only permits a high, towering shot, which is a ridiculous demand of the player in such a windy environment. Both holes are in need of better ground game options.

The penultimate hole stretches away in the distance and Egan did a fine job in filling up the space with the unique green configuration. Note how his bunker does not wall off the entire left side of the 17th green.

- Some things have improved with time; the new fifth by Jack Nicklaus in 1998 with its lay-of-the-land green peeling gracefully away from front left to back right is the most obvious.

- Pebble Beach joins Oakmont among the hardest courses for a first-time visitor to play to his single digit handicap. Others might cite Pine Valley but its large fairways and greens comfort the good player. At Pebble, even on a calm day, the player faces tiny targets and thick rough in a setting that is bound to distract.

- Don’t fret about eight, nine, and ten as you are going to pile up strokes even when playing well. The key to a good round at Pebble lies with the less known holes. It’s hard to fathom recovering from mishaps at holes one, three, four, eleven, thirteen, fifteen, and sixteen, which adds to the pressure of playing them well.

The Pebble Beach of yesteryear featured fairways more than double in width of today’s version. Egan’s greens were much larger – look at how the 9th green flairs out front left, back left, front right and back right.

- As is often the case, the most dramatic moments garner the greatest attention. At Pebble Beach, holes seven, eight and eighteen are the crowd-pleasers. Yet, all told from tee to green, we would nominate nine as the best hole, closely followed by ten.

The approach to the 8th demonstrates the enormous benefits derived from the Pebble’s jagged coastline. Such a glorious moment is not possible if the coastline was merely linear.

- Lost in the shuffle is an outstanding collection of three shot holes. In the days of hickory golf, even the second hole had great merit with its fine cross hazard 90 yards shy of the green. Today, the sixth, fourteenth and eighteenth comprise as fine a set of three shotters as those at Muirfield and Cape Breton Highlands. Why so? The uncompromising nature of their second shots puts great pressure on the golfer to get the tee ball into the fairway.

- The fourth through the tenth is surely the most inspired sustained stretch in world golf. Any of those holes could make someone’s version of Pat Ward-Thomas’s eclectic 18. How highly one regards Pebble Beach is more reflective of how its weak holes are tolerated rather than quibbling over its plethora of world class ones.

- Only the architect of Spyglass Hill would rate his course close to Egan’s superior, strategic design.

Despite everyone’s lofty expectations, Pebble Beach usually exceeds them; that is truly amazing. No education in golf architecture is complete without a visit, though one must be cognizant of just how much has changed over the decades. We hope the colorized postcards convey a sense of the great artistry that has been lost so that the course may cope with the crush of 50,000+ rounds per annum.

The End

![The Park, West Palm (Lit 9) [2023]](https://golfclubatlas.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/IMG_7092-2-scaled-500x383.jpg)