Kahuku Golf Course

Hawaii, United States of America

Kahuku represents affordable golf in an invigorating setting on the North Shore of Oahu. This view is across the graveyard that borders the par 5 2nd.

One of the charms of Scottish golf is how in so many towns the golf course occupies, both literally and figuratively, the town’s heart. The golf courses are often so much a part of that town that it is beyond challenging to imagine what that town would be without golf. Think about St. Andrews, Carnoustie, Machrihanish, North Berwick; what would the character of each town be in a golf-less world? The golf course can provide the center for that town in terms of recreation (whether golf or walks with the dog) and social interaction. Well-known courses can contribute significantly to the town’s employment and economy, such as with Carnoustie. The Scottish tradition of naming golf courses after their towns reinforces the key role that the course plays in the fabric of its environment. To many, the line between the course and the town becomes blurred, as they are often so closely associated with each other.

Kahuku Golf Course does not share this tradition, for golf is very much a supporting act on the iconic North Shore of Oahu, where surfing is king (with the Kahuku High School’s Red Raiders football team not far behind). However, flying under the radar suits this gem of a course, whose scorecard needs to state that “Shirts must be worn at all times. No slippers [flip flops] or barefeet.” Like so many favorite Scottish courses (such as Dunaverty, Kilspindie and Stonehaven), Kahuku is intended for fun, casual, inexpensive golf among friends; it was not designed to host serious tournaments or to appeal to those with bucket lists.

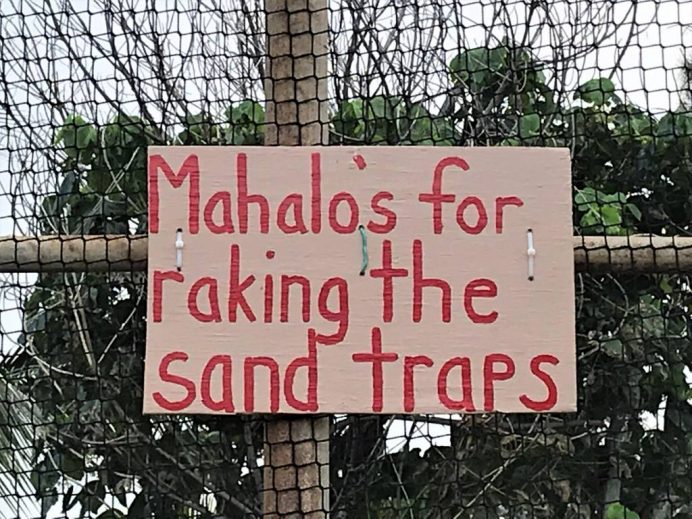

Etiquette always matters in this great game, no matter where in the world it is played.

Joevan Joaquin, Customer Service Representative at the course and former golf coach at Kahuku High School, grew up in Kahuku and remembers the many uses other than golf for the course, including playing tackle football on the 5th fairway, riding block ice down the hill by the 3rd green, parking and making out along the 7th fairway, and taking four-wheelers out onto the beach. However, golf was still a big part, even though he didn’t become became hooked on the game after his roommate at the University of Hawaii at Manoa took him to a driving range, inspiring him to invest in his own clubs the very next day.

Consider the basics of Kahuku: A nine-hole municipal course (owned and operated by the City and County of Honolulu), a barebones course maintenance and operations budget (with one example of the appealing way the fairways and rough are mown at the same height by the same equipment), the unusual mix of holes (four par threes, three par fives and two pars fours), and several unique design features from an architect (whose identity is not known to the course management and Hawaii State Golf Association). Sound like the recipe for a forgettable course? Just the opposite, as with Himalayan Golf Course, these elements combine wonderfully and complement each other to provide a course and experience that the golfer will never forget and will long to return to play again and again.

This seems an odd premise to suggest on a website devoted to golf course architecture, but could it be that an architect of the one-and-done variety (such as with Kahuku and Himalayan Golf Course) actually enjoys an advantage over professional architects? In most professions, a person becomes more skilled at his work with the more projects he undertakes (as Malcolm Gladwell would agree). However, there does tend to be a bell curve with the artistic angle – the early work is promising if raw, the middle work is the best, and the latter work shows signs of tiredness. Why is that? At first did the artists (including architects) feel as though they finally had the opportunity to show off their ideas (which had been internalized previously) and intended to take full advantage of the change to express themselves? The desire to impress future clients? The fact that they still had fresh ideas?

An architect who does not have any aspirations beyond the design at hand is free to do what he wants for the specific goal of that project. An amateur architect can also know the latitude to do what he thinks would be fun or interesting, without being burdened by the need to conform to industry norms (with the fifth green at Kahuku as a striking example of that creative freedom). We can only speculate as to the thought process of the unknown architect of Kahuku. Based on the challenging greens of the first, third, fifth and seventh holes, he was clearly not content with designing a rudimentary layout for employees merely to bunt the ball around; the architect evidently wanted to present a fun, rather than bland, set of holes and did so through a keen appreciation of the site’s special features.

He demonstrated remarkable commonsense throughout the design. Take the second hole as example. As with world-class designs such as Pacific Dunes and Ballybunion, the architect chewed up the flatter property with par fives, both here and the parallel seventh. The distant Ko’Olau mountains provide a sense of tranquility. Thereafter, the player clambers over the dune behind the green to face holes 3-6, which go over, around and back up to that dominant dune. Nonetheless, the second provides a wonderful ‘quiet’ moment before the make or break portion of the round commences.

Two of the key elements of Kahuku are its sandy soil (somewhat rare in the volcanic islands of Hawaii) and the wind.

The course was built in the 1930s for employees of the nearby Kahuku Sugar Mill. One assumes that the architect likely was to be a regular player of the course, and therefore, it was in his own interest to lay out a course that he would not tire of playing. That by itself is a fascinating point: How many courses would be different if the architect knew that he was also designing his home course? Is it any wonder that National Golf Links of America (Charles Blair Macdonald), Pinehurst No. 2 (Donald Ross) and Pasatiempo (Alister MacKenzie) all appear on short lists of courses that one person would happily play for the rest of one’s life?

Would a professional architect have designed the bold third green or the ingenuous fifth green, used the abrupt fall-offs around several greens, or incorporated only two pars fours (which tend to be the least fun type of hole to play) into the design? Unlikely for all, and the course is emphatically the better for it.

Holes to Note

First hole, 165 yards: The opening hole calls for an uncomfortable middle iron for the first shot of the day, and the tiny (less than 2,000 square foot) green with redan features requires the player to shake off any cobwebs before stepping to the tee. With the exposure to the wind and the view of waves in the Pacific Ocean beyond, this opener whets the golfer’s appetite and has him itching to see more of the course.

The opening hole captures the appeal and simplicity of Kahuku: A hole that plays harder than it looks and exposure to the elements with the Pacific Ocean as a most attractive backdrop.

A long miss on the opening hole will introduce the golfer to Kahuku’s sharp drop-offs around many of its greens.

Third hole, 150 yards: The second one-shotter features the most dramatic green site on the course, both in terms of natural defenses and proximity to the beach. At first, the extreme two-level green that drops from the right to a small left side seems to be the main challenge of the hole, but it is really the green surrounds that make the golfer thrilled to find the green from the tee. Short as well as right are sharp drop-offs from which few pars made; left is the dunesland by the beach (defined as out of bounds); and behind is an undergrowth-covered dune.

The natural setting for the 3rd green creates a demanding shot, with the beach (out of bounds) to the left, the raised green, and the drop-off to the right.

From the higher right side of the 3rd green looking to the lower, very small left side that is hard by the boundary.

Fourth hole, 110 yards: With the dunesland and wind to provide the appeal and challenge to the course, there is no need for heavy bunkering. As a result, this short drop-shot hole to another sub-2000 square foot target ringed by bunkers comes as a striking surprise. The tee shot falls from the dunes into the flat, and the three bunkers surrounding it present a varied obstacle. With the exposed nature of the tee and the difficulty in maintaining good turf on such an exposed shot where wedges are used by most golfers, the course wisely elected to stop fighting that battle and install a couple of artificial mats to be used for tee shots. Self-righteous purists may gasp as the prospect of the use of mats on a permanent basis, but the author believes that teeing areas in general are low-hanging fruit for the efforts to make the game more sustainable and encourages other courses not to shy away from this solution or to become more comfortable with less-than-perfect tees (Fano in Denmark is a prime example). It is embarrassing how much time and resources are spent maintaining areas where a golfer is allowed to tee his ball.

The simple presentation of Kahuku may not be to everyone’s taste, but the course is none the worse for it.

Kahuku features (and needs) only 13 bunkers for its nine holes, so the three bunkers on the 4th get the player’s attention.

The only shame of the attractive and challenging 4th is not the mat for the tee but rather the fact that the attractive green complex is not fully visible.

Fifth hole, 310 yards: Even though this hole occupies the part of the property that is the most removed from the ocean, this hole shines as the best on the course and the work of true genius (if only we knew whom to credit!). From the tee, the prospect is not thrilling: Just over 300 yards (which plays shorter with the prevailing wind) straightaway to a flagstick whose top half is visible. There are no bunkers or penalty areas. There is out of bounds to the left and a tree-covered dune to the right, but only a rank bad shot would find either. What makes the hole is a green unlike any other the golfer has seen: a slender, two-level figure-eight set at a slight angle to the fairway and sloping from left to right. As the trees on the right are closer to the green than the white boundary fence to the left, the golfer is tempted to err to the left from the tee, resulting in a most challenging pitch to a target that now appears alarmingly shallow and runs away from the player. Even though there is no sand or tall grass involved, finding the putting surface from just ten yards left of it is an accomplishment!

Similar to many approaches on the Old Course at St. Andrews, this view from 50 yards out on the 5th provides no idea of the challenges the golfer faces.

The ingenious 5th green – narrow, pinched and sloping left to right. Not an easy target from any distance!

Sixth hole, 120 yards: A classic for fans of skyline greens, with an uphill pitch (often with a strong right-to-left wind that makes players believe it is impossible to start the tee shot too far to the right) to a green perched on top of a hill, with drop-offs short and long. Amazingly, there used to be Ironwood pine trees guarding the front of the green, which must have presented an intimidating prospect. Originally this was the opening hole, with a starter’s hut or honesty box near the tee.

The dramatic skyline green on the 6th is enhanced by the wind-shaped tree.

Seventh hole, 550 yards: While this is the flattest hole on the course (thanks to the need to turn it into an airstrip during World War II), the 7th packs a punch thanks to a fairway bunker that is in just the right spot on the left and a two-level, figure-eight shaped green, with bunkers pinching in at the waist. When the hole is on the back part of the green and the player is not approaching the green from dead-on, the bunkers make for quite the awkward pitch.

The long 7th, with the beach and ocean to the right good for surfing (and other activities!).

A generous front hole location greatly simplifies the 7th hole, as the player does not have to negotiate the pinched waist and small, raised back portion of the green.

Eighth hole, 365 yards: With the fairway crossed by two footpaths to the beach (for surfers more than dog-walkers) and a blind approach, the eighth is the most Scottish-feeling hole on the course. From the tee in the edge of the dunes, the golfer needs to decide how close to the sandy paths (from which free relief is not available) to place his tee shot. With the prevailing wind from behind, he may choose to lay back or to bang away with his driver, in hopes of getting lucky with a lie and stance. The blind approach aimed towards the tall directional post behind the green must be accurate to find this narrow, pitched target.

Two sandy paths cross the 8th fairway to take surfers to the nearby surf break. The golfer must decide whether to challenge them from the tee and get lucky with the lie or lay back and use the directional post for his approach.

Ninth hole, 475 yards: This rolling three-shotter points the player back toward the simple clubhouse and offers a new backdrop of the Ko’ olau mountain range, more garden-like scenery than links-like. This straightaway hole leads to a green that is sheltered between the last hill of the fairway and the small ridge behind on which the clubhouse and parking lot sit. A large bunker dominates the front of the green, but there is just enough room (and contour) to allow a long second shot to bounce onto the front-left part of the green between the front bunker and the left bunker.

This view from behind the 9th green shows the opening at the golfer’s front-left that is just wide enough to tempt him to chase a 3-wood onto the green.

While the golf course was built in the 1930s for employees of the Kahuku Sugar Mill, it was later leased to the City of Honolulu. After a developer owned the property for a stretch but was ultimately not able to do anything because of strong local opposition (where a popular rallying cry against new developments remains “Keep the country country”) the City purchased the course in 2017.

There have been proposals by some to expand Kahuku to 18 holes and increase the number of rounds played there to help the City of Honolulu generate more revenue to support its many needs. It is a tough situation, as a large part of the author would hate to see a single aspect of the course and operation change. On the other hand, a far worse fate would be if Kahuku ceased to be a golf course through insufficient revenue. In that regard, change to the golf course is much preferable to no golf course. However, if Kahuku does need to evolve to survive, the utmost care and sensitivity are needed to ensure it remains the special course and place that it is.

Surfing and golf co-exist quite nicely; in fact, it is surprising that there are not more examples where they do. After all, with one sport in the water and the other on land, there is no inherent conflict – and what golfer doesn’t enjoy playing by the sea? At its best, each sport highlights the greatness of nature. An enduring example of this relationship is the well-known surf break “Seventh Hole” immediately next to, you guessed it, the long seventh at Kahuku.