Cedar Rapids Country Club

Iowa, United States of America

More has been written about Donald Ross than any architect living or dead. Ignore the plethora of kind remarks; it’s more remarkable that less criticism has been leveled at him than any architect in history. Why is that? The answer is multi-faceted but one reason is that his work has touched so many people. Be it the Northeast, Southeast, Midwest, Denver or California, Ross was there and wherever his involvement, the end result became a credit to the game. Ross’s travels and labors are enormous considering the age in which he lived and his accolades are commensurate to his effort.

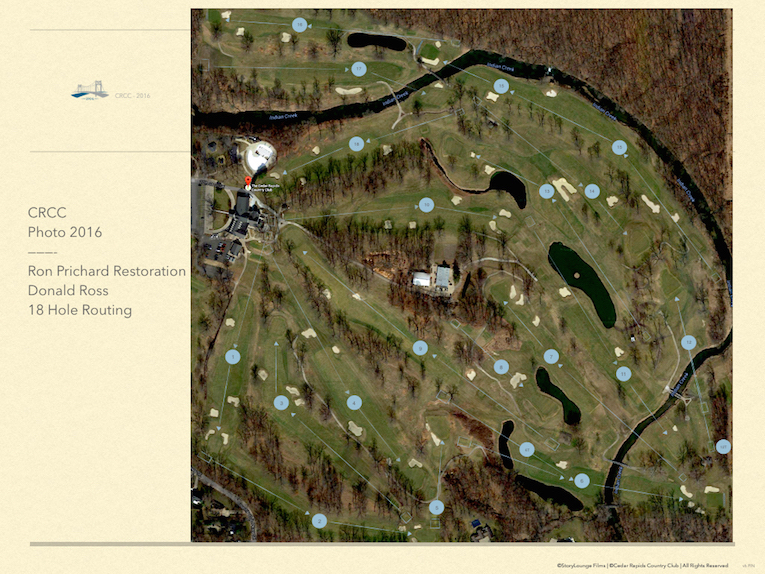

Not all Ross courses were created equal, some he visited, some he did not. Each design has a unique story behind it and so it is with Cedar Rapids Country Club, the only Ross course in Iowa. The Great Man himself was here over 100 years ago in 1914 when he expanded the course to 18 holes by routing holes across a disparate environment of rolling hills and river valley. Recent work here was not only a hugely successful restoration but a beacon for other clubs considering change. In short, the in-house work completed by Ron Prichard and his Design Associate Tyler Rae between 2011 and 2015 is the most economical restoration producing top-drawer results of which the author is aware.

Vaughn Halyard was the Golf Chairman during the restoration and his GolfClubAtlas October 2016 Feature Interview is mandatory reading for any club with a Golden Age course. It begins with Halyard neatly summarizing the founding and early years of the Club:

The interest in golf was sparked in 1896 when George and Walter Douglas, founders of Douglas & Co. the precursor to the Quaker Oats Company, returned from a visit to Scotland with golf fever. With their brother Will, the Douglas’ subsequently laid out several fairway-like environs in Judge Green’s low lying pasture near the Milwaukee Road rail main line running north east out of Cedar Rapids. In 1900, sharing the pasture with livestock soon resulted in tee time conflicts causing a group of ten to lease 30 acres that are now part of the Brucemore Mansion, a National Trust for Historic Preservation site. They built a course that would support more dedicated play with fewer bio-animal hazards. In 1904, as the city grew, a more permanent location was sought resulting in the formation of the Country Club Land Company whose 96 subscribers raised $15,000. The club’s current location, one hundred eighty acres along Indian Creek, were purchased at $75 an acre accompanied by a five-fold increase in annual dues from $5 year to $25. A larger clubhouse was built in 1904 as the Indian Creek adjacent property was converted into a nine-hole golf course with clubhouse.

Scottish golf course architect Tom Bendelow, designed that initial nine hole course where the longest hole measured 400 yards. In 1914, the land company exchanged some hilly terrain west of fairway #1, for 36 acres of more level ground providing space for tennis courts. In 1914, Donald Ross was hired to lengthen the course from nine to eighteen holes. It has been verified that Mr. Ross was sent to Cedar Rapids by Ralph Van Vechten, older brother of the famous writer and photographer Carl Van Vechten, to extend the course. He made a site visit to Cedar Rapids during a trip west that included visits to Illinois, Lakewood and the Broadmoor. Plans were generated from that visit and there is published verification that Ross came physically to lay out the course in its present location. The plans were received sometime during late fall, November- December 1914 as reported by the Cedar Rapids Daily Republican. The bones of both the Bendelow and Ross routings have been reinvigorated and celebrated by Ron Prichard’s restoration. Prior to the Bendelow routing, the land at current location was an undeveloped mix of woodlands, prairie and sprinkling of swamp. Ross incorporated parts of the Bendelow course within his routing.

Design Associates J.B. McGovern and Walter Hatch had yet to join Ross so construction was carried out by locals. Apparently, the end result was not especially bunkered as Ross relied on the topography and Indian Creek to provide the challenge.

We all know what happened next. Life was grand until October 29th, 1929. The economic depression in North America and subsequent world events exacted their toll as did tree planting which became vogue during the 1960s. The property morphed into something different and lost its character. Amoeba shaped tees and extraneous mounding added by a Chicago architect further diluted the presentation of this Golden Age course. Additionally, Halyard points out, the city of ‘… Cedar Rapids had expanded well beyond and around CRCC. Our rolling Hill/Valley site sits in the Indian Creek Watershed. Our valley vistas are framed by hills which form a geologic gauntlet that bends at the edge of CRCC. Urbanization of historically rural areas upstream created a spate of flash floods on the property. Prior to the restoration, when it rained hard, we closed.’

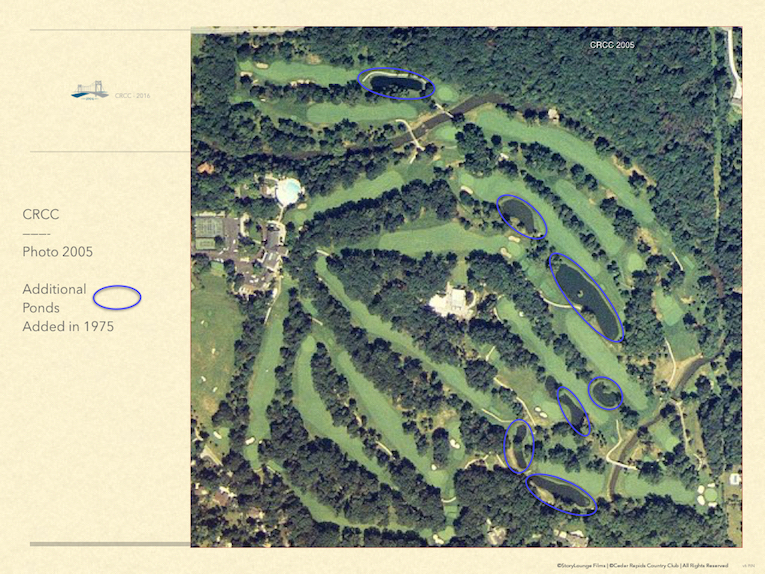

When asked what the impetus was for consulting Ron Prichard, Halyard responded, ‘The course was fatigued, had become costly to maintain and the greens were unhealthy. The intent of our CRCC project was to reinvigorate appropriate Ross characteristics while simultaneously delivering playability for the modern game. Trees and floods altered the original layout moving it far afield from the original sprit of the Ross design. Historical aerials illustrate that 1970 to 2000 was the most prolific era for tree planting and the contraction of fairway and putting surfaces. Additionally, a series of ponds were cut into the property intended for flood and drainage relief but badly out of character with the Ross routing.’

Prichard’s initial visit to the Club was in 2011, which resulted in him submitting a Master Plan. Ross’s plans didn’t exist and there wasn’t much historical information from which to work. Prichard, whose career is littered with successful Ross projects, did what he does in such situations: read the land and imagined what Ross would do. Where there was a little rise or knoll, he inserted bunkers, if they would add to the golf, as he did near the fourth and fifteenth tees. He even sketched in a hairpin bunker, the like of which is found at Inverness and Aronimink. Tree removal, tee work, a complete re-work of the bunker schemes, and green expansion dominated the to-do list. Here is the rub: 2011 wasn’t a great time for private clubs in the United States. The impact of 2008 Great Recession was still being felt and undertaking a costly capital campaign wasn’t in the cards. Yet, the board was duly impressed with Prichard’s vision and they realized action was required.

Restoration Committee Chair Jason Haefner (who later became Club President) was instrumental in gathering support. As a demand for action grew, in stepped Greenkeeper Tom Feller. He knew Cedar Rapids possessed something special and that it wasn’t the time to undertake a capital campaign. As he says, ‘It was time to get creative’ and he suggested that most of the work be done in-house. Prichard and Rae were open to the plan. Head golf professional Dustin Toner writes, ‘Tom Feller decided to be bold, jump in head first and take the risk that many superintendents would not be willing to take. If he had failed, it would have jeopardized the club in many ways from course quality, future capital and operational budgets and potentially the greatest revenue line at any private club, membership. Had he failed, it could have been the end of his tenure at CRCC.’ From Feller’s perspective, he had done enough construction to know what he was signing up for and he didn’t have one shred of doubt that they were doing the right thing. Plus, he took the risk because he enjoyed complete confidence in his First Assistant, Tim Salazar, who assisted in managing irrigation projects, tree removal, drainage installation, and interpretation of Ron and Tyler’s drawings.

If Feller and his crew could shoulder the workload, the project could proceed. And that’s what happened. Rae returned in the spring of 2013 and work was done to three of the most visible holes, the first, fourth and tenth. All three play away from the elevated clubhouse so that splendid views of those holes are enjoyed from the patio. Rae notes that working in the rich Iowa dirt was a pleasure.

… and the view in 2017! Talk about transformational, the impact of this work helped create momentum.

As evidenced by the ‘before’ and ‘after’ photographs, it’s no surprise that the work opened to raves and support swelled within the club to fully execute the Master Plan. Five more holes received work in the fall of 2013. Rae would rake in the general shapes on the dozer while Feller was on the excavator, setting the stage for the drainage and sod work that quickly followed. Most of the work was done in the shoulder seasons so that the course never closed. Temporary greens were employed only when the putting surfaces were being expanded to the edge of the green pads. Ultimately, the work concluded in 2015.

Nothing was hurried and there is a beauty to be found in the slow measure of the work. After years of doing new construction, some contractors make things too smooth, too tidy, too new so that the old world look eludes them. Feller and his crew hadn’t built anything and had no bad habits to break. Everyone – the Club, Prichard, Rae, Feller and his crew, the members – stayed with the mission. ‘We wanted an antiquated course when it opened that was fit for the modern game.’

Toner was impressed, ‘Tom’s creativity was one of the most intriguing things to watch as the project was buttoned up. When forward tees were moved Tom would transfer bent grass to expand the fairways, saving time and financial resources. Feller found local sand from the Iowa River that the USGA has rated highly and he shaped several tee complexes himself over the winter months.’

The end result was the removal of hundreds of unhealthy trees, a 35% increase in fairway width, and a 22% increase in green size. The number of bunkers increased from 26 to 59 but that is only part of the story. The key was that the bunkers were placed where they were relevant for today’s game. Playing angles now hinge on the placement of hazards rather than tree growth.

A primary beneficiary of the work was the seventh hole. As seen in the 1975 map (above), very un-Ross like ponds were found left and right of the fairway. Rae filled in the right pond leaving a retention area that Indian Creek fills during floods. What a great solution – all sorts of varied lies are served up in that low lying area but at least the golfer gets to play a shot rather than incurring a penalty. One litmus test for a restoration’s success is how much the worst holes/features are improved and Cedar Rapids passes that test with flying colors.

Indian Creek is in the foreground and the shallow depression to the right of the 7th fairway is infinitely more interesting – and functional – than the pond that was there.

Shockingly, the back markers stretch the course to more than 7,200 yards which means nothing to the author as that distance would take too long to walk. However, the importance of length was driven home from a conversation with Toner. There are two well-placed bunkers down the left of the sixteenth. As the author imagined how the bunkering impacted play for both hickories and steels, he asked Toner how he played the hole. The casual, non-braggadocios response, ‘Well, from this tee, I might try and drive the green.’ We were standing 350 yards from the front edge of the green (!) and the author was surveying a patch of fairway 50 to 90 yards shy of that surprise answer! No point in denying how rapidly the game has changed in the past decade and keeping Ross’s handiwork intact during such times is more challenging than ever. At 4,600 square feet, the sixteenth green (which was rebuilt by Rae) is the smallest target on the course, so hitting it with any club (including a driver!) is never a given.

Total cost for the entire project? $660,000. That’s right, there are still a few outposts in this country – Maine, Iowa – where common sense prevails. What was accomplished here is a rare example of actually receiving value for money. Even a Green Committeeman in the United Kingdom, where many clubs abhor America’s waste, would congratulate Cedar Rapids for a job well done. In all respects, the intelligent decisions and economical work undertaken here epitomizes a Midwest sensibility of the highest order. Have a look at some of the standout holes below and see if you don’t agree.

Holes to Note

(Please note: the yardages below are from the 6,624 yard blue tees, not the black tees which tack on another 600 yards. We cite the black tee distance in hope that one day this course will be seen on television as host to an important event.)

First hole, 340 yards; This quintessential Donald Ross handshake opener features a high tee, low fairway, elevated green that is the devil to hit. Before the restoration, the fairway was bowling lane narrow between trees and the task was merely defined to hit a straight drive. Who can hit the straightest ball is something that can be settled on a driving range; golf is meant to be something far more. If the player isn’t made to think, then he is unlikely to remain engaged through the course of play. Here, staggered bunkers were introduced in the landing area and now every class of player has a decision where to aim and what club to hit from the tee. The steeply pitched back to front green is over 100 years old and one of the course’s most canted putting surfaces.

The proximity of the dining patio to the back marker is evident. While the tables and chairs have been stowed for the season, the deep fairway bunker 85 yards short left of the green is on sentry!

Second hole, 365 yards; The golfer on the second tee is quickly alerted to the up-and-down nature of the front nine as he faces terrain opposite to the first (i.e. low tee, high fairway, low green). As with numerous other holes, there is a gentle bend (not a sharp dogleg) in the fairway that needs to be considered from the tee. In this case, the fairway bananas from right to left and its expansion left and right exacerbates its crowned nature. The player dearly wants to hit a draw but if it is too hot and scuttles left, the extra short grass will propel it somewhere less advantageous.

This view of the green from near the fairway’s crest surely confuses the golfer who thought of Iowa as farm country.

Third hole, 380 yards; This hole features the only true dogleg on the course and is capped with a wonderful two tiered green of antiquated flavor. In general, the course’s most confounding putting surfaces are those out of the flood plain and Rae thinks he knows why: ‘When Indian Creek floods, sediment is deposited on the greens in the river valley and while that sediment is scrapped-off, it nonetheless collects in the low areas and over time, the subtle dips and hollows have been lost. Most of my favorite greens – the 1st, 2nd, 3rd, 9th, 18th – are on the elevations away from harm. The same would apply to the 12th and 14th as well.’

One of Rae’s favorite pockets on the property is the shallow valley in which Ross located the 3rd fairway and finished the hole at Bendelow’s 3rd green, which is wickedly sloped from back to front.

Rae ringed the back of the green with irregular mounds, simultaneously diverting rain water off the hillside and given the green complex an antiquated flavor.

Fourth hole, 400 yards; Ross utilized the shoulder of a hill within the fairway. In the days of hickory, a golfer would hit a ball down the left center and let his tee ball cascade off the slope and peel right to open up the approach. A new back tee stretches the hole to 475 yards and re-establishes the strategy that applied when the hole measured 380 yards in Ross’s day. Flexibility to find back teeing areas preserved this hole’s charm/meaning and highlights how a 100 year old Ross hole can retain its playing qualities.

Over the course of 18 holes, the golfer is asked a variety of questions. Most of them center on how to use certain landforms to his advantage as well as to circumnavigate Indian Creek.

Fifth hole, 150 yards; Toner enthusiastically expounds on the transformation of this one-shotter: ‘The fifth green complex has taken on a new life. Trees had encircled the green and dictated its small, round shape. After their removal the green was expanded in all directions, recapturing much of its original characteristics. Bent grass was extended front right of the green to provide another option for the player for a front pin. This slope plays like a Redan kicking the ball forward and to the left. With the target of the green enlarged by nearly 50% and the added Redan feature, the hole plays much easier for a novice player. However, for the tournament player it can be extremely difficult as we saw in our Golf Week Challenge. The shortest hole on the course played that day into the wind to a back left pin and finished the day as third most difficult!’ Think about the magnitude of that statement. A bland, modest length hole evolved into an option-filled classic with teeth. What more could any club possibly ask for?!

The beautifully presented 5th. Note the rise and complimentary graceful swoop down, left and onto the putting surface.

The tee ball becomes more difficult once the golfer appreciates the strife that befalls him should he be long.

The different landforms intrigue the eye as the hill of the 5th gives way to the river valley at the 6th.

Sixth hole, 440 yards; The course was inaccurately described to the author as ‘an interesting mix with the front nine set through hills and the back nine in a river valley.’ That statement isn’t precise as we head into the river valley now. Indeed, the seamless interplay between the hills and the river valley occurs on both nines, making variety a cornerstone of the overall design. A trio of bunkers arise 65 yards from the green and diagonally front it without ever abutting the putting surface. They constitute the perfect hazard for a three shotter of modest length as no one wants the dreaded 45 yard bunker shot.

Today, the 6th is open and expansive, not to mention a back tee that makes the hole nearly 500 yards. From near where this picture was taken, 14 holes are visible. Previously, the teeing area was encased in trees and the golfer had no sense of place.

A bridge crosses the river that bisects the fairway 190 yards from the green. An attacking golfer has to clear two diagonal hazards to reach the green.

Even if the golfer clears the three bunkers, he may find this soft fall-off, which collects many a shot. Rae gently raised the green and added character to what was one of the least interesting putting surfaces on the course. As with any Ross design, par is defended at the green.

Eighth hole, 180 yards; What an interesting play on greed with a lake left, field right and a large putting surface in the middle. Say what you will about blind shots and the nuance they may create (the author loves them and cites the next hole as a prime example why), but when everything is clearly revealed, the result is on the player and not in the lap of the Gods.

How much duller would this hole be if the water was flush with the green or if deep bunkers were on the right? As it is, imprudent tactics are encouraged, a far more clever way to undo a player.

The golfer who misses the green right has short-sided himself today and will need good fortune (and likely a ten footer) to get up and down.

Ninth hole, 520 yards; Typical of many Golden Age designs, the clubhouse sits on the property’s high point and the opening holes of each nine cascade down while the closing holes stampede uphill. Three shotters are a fine way to cover both dull ground (e.g. Pacific Dunes) or severe terrain (e.g. Yale). This is an example of the latter as the hole climbs mercilessly from the tee before ending at one of the course’s most clever green complexes. Prichard’s created a wonderful, soft punchbowl green after expanding the putting surface by as much as 20 feet in some directions including the high shoulders at the rear. The green slopes predominantly from back left to front right affording a vast number of hole locations. Uphill holes can be demoralizing but if there is an amiable target for the elevation, it is surely a gathering punchbowl.

After a big drive, the golfer launches a shot up and over the crest of the hill in hopes that it takes the far slope and tumbles some thirty yards downhill …

… to the open green. Be it the second or third shot that clears the crest of the hill, the golfer enjoys the stroll and the tantalizing prospect that his approach is close.

This view from behind conveys the thrilling opportunities provided by the forward portion of a punchbowl green.

Tenth hole, 375 yards; Sure enough, back down we go. Just like holes one and two, the contrast between holes nine and ten could not be more refreshing. The tenth green and the ninth tee are at grade to one another and the same is almost true for the ninth green and tenth tee. The tee ball at nine is stunted due to the fairway’s uphill nature while at ten maximum run out is afforded. In fact, the good player might be keen not to get too close to the tenth green under certain circumstances.

All is on display at this sharp downhiller, including the day’s hole. A forward location may well tempt one to lay back a bit to leave the prescribed distance for the desired spin for the approach.

Eleventh hole, 425 yards; Here’s the first of five appealing flat holes. A carry of nearly 240 yards is required from the blue tee to get past the sole fairway bunker that protects the most expeditious route to the green. If successful, the golfer enjoys a mid iron approach. If unsuccessful, that is, the tee ball lands in the bunker or rough, carrying Indian Creek fifty yards short of the green becomes a chore. Good driving matters at Cedar Rapids! A missed drive doesn’t mean searching for the ball but it does mean that the player finds himself out of position and challenged to make par. Many of the crescent-shaped holes build upon the tee ball, and the eleventh is a prime example benefitting the golfer who can fashion his drive.

Golden Age architects left it to the player to decide his or her own route to the hole. Cedar Rapids again enjoys that characteristic.

Twelfth hole, 220 yards; There must be something special about the land when a one shotter is bunkerless and really good. In this case, a 1 1/2 acre rise in the valley floor was exploited by both Bendelow and Ross. Currently, the twelfth and fourteenth greens back up to one another on this elevated mound, rumored to be an Indian burial ground. The triangular twelfth green was enlarged from 5,100 to 7,200 square feet during the restoration but it isn’t the 40%+ increase in size that matters but how so many of the best hole locations were recovered. Almost ten hole locations were recovered along the left, in the far back where the green narrows, and along the right where a tightly mown bank whisks balls off the side. Toner advises that the hole location alters club selection by as many as four clubs, so be alert on the tee. Indeed, the hole’s flexibility makes it one of Rae’s handful of favorite holes: ‘Can you imagine having an event here? One day the flag is in the middle of the green and is played from the 285 tee. The next, it is played from the white tee at 180 yards to a back hole location where the green narrows and you might play a bank shot. It calls for two wildly different shots.’

Golden Age architects didn’t mind asking the player to hit a driver to a par three green. In fact, some, like William Flynn, thought it was a weakness not to. A new black tee allows this hole to play as long as 285 (!) yards.

The joy of a long par three can be determined by the amount of time it takes for a shot to play out. Here, the golfer is wholly attentive to whether his ball climbs the five foot rise in front of the green or, perhaps, ricochets off the left side wall. It is a shot to remember.

This back hole location didn’t exist prior to the restoration and the recovery of 10 yards of putting surface in the rear.

Thirteenth hole, 405 yards; Terrific, even if the high to low point on the hole is merely three feet. Tee balls are slotted between a pond left and a horseshoe bunker right but it’s the green complex featuring short grass on both sides of its raised three foot pad that shines. Eight yards short of the green lies a hated bunker. As it was being built, more than one member voiced disapproval but that only confirms that the hazard was well placed. Hazards directly in the line of play are always the biggest irritant; every course could use a few more!

The prospect of finding water left pushes many a tee ball right into this hazard where there’s no guarantee of a level stance/swing.

This maddening pit of a bunker receives plenty of visitors. Its irregular shape is a thing of beauty and speaks as to the hands-on, unhurried approach that the project enjoyed.

Rae scrapped away the ‘fat’ that had been added by modern architects to both sides of the 13th green. After the removal of the framing mounds the perched green is once again a most handsome target. Feller calls Rae’s bulldozer work here ‘phenomenal.’

Fourteenth hole, 345 yards; Yes, we are on the middle of the river valley but the golf is anything but uninteresting as this hole is capped by the back half of the enormous mound first encountered at the twelfth. Here, the mound is even taller and hitting the correct short iron approach is one of the day’s finest accomplishments. Toner shares his local knowledge and states that this green gets baked and wind-polished more than any other putting surface. Chasing after hole locations by flying the ball deep onto the green isn’t nearly as wise as using the green’s firmness and its high left to low right cant to feed balls to the desired area.

Benedelow had fashioned his 5th green on this mound but his approach was from the right. Ross’s orientation enables the massive 7,800 square foot putting surface to play like a Reverse Redan with a high left to lower back right cant.

Typical for a Reverse Redan style green, front left hole locations are the most diabolical and those back right, like the one above, are the most fun.

Fifteenth hole, 565 yards; There should be a consequence for a failed second shot on a three shotter. One design ploy is to place the green forty yards beyond a stream. That way if anything goes awry on either of the first two shots, the golfer finds himself in a pickle. At 627 yards from the Black, this is one of the longest holes in Iowa and like the 285 yard twelfth is a neat example of how the architects enabled length to mirror fun.

Several ‘top shot’ bunkers were installed as part of the restoration. This one is a mere 90 yards from the blue tees. Imagine the hole without it and you gain an appreciation for how it breaks up the landscape.

Seventeenth hole, 395 yards; The old back tee became the blue tee after Prichard found a pocket fifty yards back. Now, instead of hitting toward a narrow fairway with a weeping willow as the aiming point, the golfer aims at the Swinging Bridge. Assuming a forty yard long bunker is avoided on the right, the golfer is faced with one final approach over Indian Creek. Appropriate for a penultimate hole, this green is a mere seven paces from the water and is the closest to Indian Creek of any on the course. Again, pressure is placed on the golfer to find the fairway from the tee. Numerous perimeter hole locations were returned after the putting surface was expanded back to the edge of the green pad, increasing the green from 5,000 to 7,200 square feet.

Front hole locations are particularly troublesome on this original, beautifully perched green that has rarely flooded.

Eighteenth hole, 350 yards; This uphiller crafted as Bendelow’s ninth has been in use for over 110 years and has been the only Home hole that the course has known. Its green was built when greens ‘stimped’ at 5 or 6, so it is an absolute terror at today’s green speeds as it features the most pitch of any on the course. Ball position is critical and a twenty foot putt from below the hole is infinitely more appealing than a ten footer from above. The beauty of this finishing hole is that it preys on the nerves, which is the last thing that any golfer desires at this stage.

For takeaways, what’s not to admire? High quality work was performed at a fraction of what it would have been if the work was contracted out. Feller’s entire team remains with him to this day, so the work wasn’t too onerous. An enormous amount of pride exists among the crew for a job well done. As for the members, they enjoy an infinitely superior playing experience without being burdened by ongoing assessments. In fact, as a new found appreciation took hold in the region for this course, guess what happened? 88 new members have joined since the work was completed in 2015. Talk about a ringing endorsement!

To be sure, the tack of doing this much work internally isn’t for every club. The Greenkeeper must have the vision, talent and personality to drive such a project and the club board needs to be staunch in their support. However, in this mind-numbing age where clubs are signing up for $10,000,000+ restorations that leave the course starched and pressed, this hands-on approach has huge appeal. One of Prichard’s legacies will be that he led many projects that were both cost effective and transformational. To that very point, the author is thrilled to report that Prichard and Rae are in the process of replicating this in-house method at three more courses: Northland in Minnesota along Lake Superior, Riverton in New Jersey, and Riverside in New Brunswick, Canada.

Where does Cedar Rapids fit within the lexicon of Ross courses? It isn’t on the Atlantic like Seminole or have incredibly sophisticated greens like Pinehurst No.2 but it possesses something equally important and that is a mix of holes that any member would delight in playing on a regular basis. The hills and creek constitute an oasis even though the Club is just over two miles from downtown. Such a secluded environment so close to home and work is a rare delight. So too is finding a course with so many good holes and so few weak ones.

![The Park, West Palm (Lit 9) [2023]](https://golfclubatlas.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/IMG_7092-2-scaled-500x383.jpg)