Yeamans Hall Club

South Carolina, United States of America

Raynor’s restored classic architectural features mix with unsurpassed lowcountry charm to provide one of the game’s most splendid experiences.

Mozart and Haydn wrote symphonies in three movements and many Golden Age courses have played out over three ‘movements’ as well. There is the beginning in the Roaring 1920s when the architecture expressed a flamboyance that matched the country’s mood. Then a lengthy slow period, started by the Great Depression, followed by World War II and then perpetuated by a general malaise and lack of understanding by clubs as to what they possessed. Sixty years passed from the Great Depression until a renewed interest in classic golf course architecture emerged and restorations took place that returned enjoyment to their respective designs.

As for symphonies, Beethoven elevated the art form and he standardized on four movements. Mozart’s 41st symphony is considered his finest effort and it too has four movements. Regarding golf, the ongoing transformation of Yeamans Hall that commenced in the late 1980s and continues to this day is one of the most remarkable ones in golf. The restoration itself can be broken into two movements and as such, the evolution of Yeamans Hall can be viewed in four distinct movements.

The founding of the Club was the first, which happened to be by New Yorkers. They acquired a 1,000+ acre tract of land ten miles outside Charleston that had been a working plantation in the 1700s under Lord and Lady Yeamans. They contacted Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr., who visited the property in 1915. World War I intervened but the parcel had clear appeal. Two sides were bordered by a broad savannah while the interior of the property rose some forty feet above sea level and featured an uncommon amount of topography for an area with the word ‘low’ in it. High season at this winter retreat would be November through April, which dovetailed nicely with a good time to be removed from the Northeast. Certainly, the original members appreciated the shorter train ride than those that pressed on to Florida.

Even though Donald Ross visited the property, Seth Raynor was ultimately hired and work began in 1923. The course opened in the fall of 1925 and Raynor was on hand in October that year, fully satisfied with the end result. The project enjoyed the talents of William Nugent, the Superintendent of Greens Construction for other Raynor’s projects. On a sad note, Raynor passed away at the early age of 51 years old, just a few months after having seen the completed Yeamans Hall.

The best way to describe the course that Raynor saw before his passing is ‘feature rich.’ Nearly half the holes move up and down over fifteen feet. Unlike Yale which is a sturdy walk, Yeamans is a walker’s dream and rare is the man who stops after playing a mere eighteen holes. As the land wasn’t hilly, Raynor was free to place hazards where they would lend the most value. More than 105 bunkers populated the course the day it opened, an impressive tally even for Raynor. And they weren’t small either. There was the 51 yard long one that patrols right of the Road Hole green and plenty of others longer than 30 yards too.

As for the ultimate targets, the rolling greens averaged over 8,000 square feet and were full of every famous feature that Raynor’s mentor, C.B. Macdonald, loved in Scotland. To boot, a unique aspect here was the incorporation of some sort of a vertical spine in 1/3 of the greens, namely four, five, nine, thirteen, fifteen and sixteen. These spines are much more interesting than the conventional two tiered greens that gained favor in modern design after World War II.

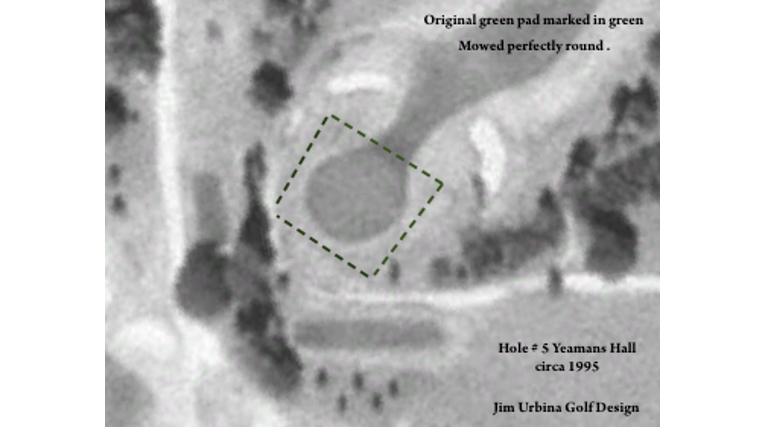

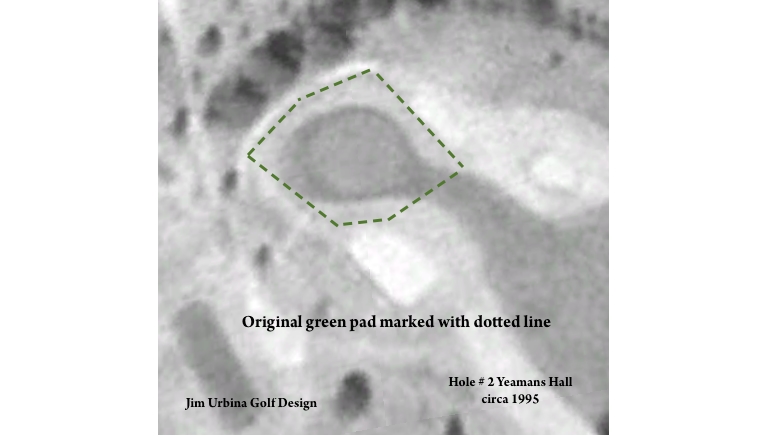

What more could a golfer want from a design? Seclusion, combined with hazards directly in the line of play and compelling targets to which to hit. Alas, like with every other Golden Age course, the period from the Great Depression in 1929 through the 1980s weren’t kind. The second movement for Beethoven was frequently a slow one and so too it was for Yeamans. Raynor’s bunkering schemes and greens became compromised. Greens like the second, fifth, seventh, and sixteenth shrunk by more than half with the once large, boldly contoured putting surfaces becoming bland circles. False fronts to greens like those at the fourth, eleventh and fifteenth, which encourage run-up shots, were lost. Rather than having the putting surface flush to the edge of Raynor’s infamously deep bunkers, the greens in some instances had pulled back twenty (!) paces. In addition, the strategic merit of Raynor’s fairway bunkering faded as they were either grassed in or removed altogether.

Now for the third movement. Beginning in the late 1980s, the Club began to reverse the neglect that the course had suffered. First, a past Green Chairman, Henry Terrie, created the ‘Friends of Seth Raynor Society.’ This entailed a donation of $50 per member per year in an effort to raise a little money for restoring one or two Raynor features each year. Over the next several years, this action led to restoring the thirteenth green, which helped highlight the hidden potential that the course possessed. Eventually, a fund-raiser was conducted in 1996 to restore the remaining seventeen greens.

The Club then found the appropriate professional architect to oversee the project. They had no interest in hiring a name ‘architect’ with little experience with Raynor designs – they were result oriented. In Renaissance Golf Design and Tom Doak, the Club found an architect who understood Raynor’s work and came highly recommended from his restoration work at Camargo, a Raynor gem outside of Cincinnati. The Club’s insight proved wise as Doak’s team later went on to work at Chicago Golf Club and Shoreacres as well as create Old Macdonald at the Bandon Resort.

Doak and his men, in particular Jim Urbina, went to work in May 1998, and the greens were – remarkably – back in play by September of that same year. The greens were restored to 140,000 square feet from 80,000 square feet, a stunning 75% increase in size! Jim Yonce was the Greenkeeper at the time and took great pride in fostering Raynor design aspects throughout the course. Indeed, Yonce’s discovery of the original maps and survey equipment set the stage for so much that was to follow.

The end result was a superior set of greens with classic features including 90 degree corners, thumb print depressions, a Maiden green brought back to its full glory and a host of greens with interesting spines of the kind that Raynor was fond of building. One result of having greens with such character is that the Club has tremendous latitude in how hard/easy they choose to set up the course. Take the third hole for instance. If the hole is in the gathering horseshoe or just shy of it, birdie becomes realistic. However, put the hole just behind or on either side of the horseshoe and the golfer looking for a level putt is afforded a much smaller effective target. A seven foot deep bunker directly behind the green snares a slightly bold approach. Indeed, saving bogey from the back bunker to a short sided back hole location can be an accomplishment in itself.

At this point in its history, the author started to have the great fortune to see the course on an increasing basis. By 2010, I had concluded that the greens might well be the finest set in the country. In fact, I wrote in Doak’s Confidential Guide Volume 2 in 2015 that ‘There is no place I would rather play in the South.’ Such sentiment was prompted in part by the attention to detail with, for instance, short bunkers on the Redan and Eden being re-installed. The design seemed to be approaching flawless. Hindsight has shown how wrong I was, as perfection was saved for the fourth movement.

In the fall of 2015, an extratropical storm was unkind and then an additional two feet of rain were deposited in what amounted to a once in a generation event. Both the fairways and the putting surfaces were left in ruinous conditions, which was heartbreaking because much of the game here centers on the ground conditions. The task to right the ship fell on Brooks Riddle, who had become the Greenkeeper in May the prior year. He determined after performing several trials that the best plan was to convert their 419/Common bermudagrass fairways to the newer variety of Bermuda called Celebration. He notes, ‘We decided to use Celebration because of its ability to tolerate two of our biggest pests, Bermuda grass mites and nematodes. One of the issues we had with our old fairways was the inconsistent playing conditions presented by Common Bermuda because it lost its leaves in the winter time, creating areas where golfers would hit their ball off dirt. The Celebration Bermuda proved through our trials to maintain a very tight, thick canopy during the winter time, enhancing the firm and fast playing conditions which best define Yeamans Hall.’

As part of the re-grassing the entire course in summer 2017, strict attention was paid to recreating the size of the playing corridors and playing angles that existed in Raynor’s day. Nearly eight acres worth of fairway were gained, much of it by moving fairway lines outside of fairway bunkers. Huge beneficiaries were the fairways at the fifth, seventh, tenth, twelfth, seventeenth, and eighteenth. As the course presently stands, a positively stunning 35 bunkers are primarily surrounded by fairway. The author knows of no other course with so many central hazards in the United States. Without question, Yeamans Hall is one of the most intelligently bunkered and presented courses in the country.

Jim Urbina, who became the Architect of Record in 2009, can’t believe his good fortune to have been associated with this restoration for twenty years. He says that patience has been the key. Nothing was ever hurried but every aspect of the design was under review. The reinstallation of central hazards that define certain template holes like the Bottle and Lido weren’t done simultaneously as such teeth-gnashing features can upset the momentum of any project. The Bottle hole was tackled in 2007 and it wasn’t until the summer of 2017 that the central bunkers at the Lido were brought back. How that would make George Bahto happy! He wrote in The Evangelist of Golf in 2002, ‘Sadly, it appears no unaltered difficult versions remain. Memberships unable to appreciate strategic excellence of design filled in most fairway bunkers – negating the design strategy.’

Another example that highlights what Urbina did in 2017 is the transformation of the Punchbowl seventeenth. It starts at the tee, which was returned to grade, a drop of some three feet. Urbina notes, ‘With the teeing grounds set at the right grade now, Raynor’s bunkers rise out of the ground and make the green site even more tantalizing.’ Ahead, a front left bunker was oddly found twelve yards prior to the green. It didn’t appear that way on Raynor’s plans and so the decision was made to push it flush to the green and in doing so, give the bunker wall appropriate height to help produce a proper Punchbowl green. This hole was already a fan favorite but almost to a person, the improvements here have come to symbolize the work accomplished over the summer of 2017.

The Punchbowl green complex has been made all the more appealing by the return of this high wall bunker tight to the green. It acts as an important counter to the wraparound bunker back right.

With the Celebration Bermuda on the fairways and Champion G12 on the greens, the course is at an elite level. Other than the Short and Alps holes, every green accepts a running shot and Riddle insures that the playing conditions exist to try such shots. Can one skip the ball back onto the top tier of the Plateau green? Can the golfer scoot his approach up the false front at the Bottle hole? Can he sling a hook down the Redan green? How about chase a ball up the bank of the Road Hole green? Etc., etc. These are the fun dilemmas that make golf at Yeamans so engaging for both the Tiger and the less accomplished player. Such wouldn’t be possible without the firm, uniform playing conditions that Riddle provides.

Cumulatively, the holes share a characteristic – to lose a golf ball brings shame on one’s family. Along with Pinehurst No.2, this is one of the few top shelf courses in world golf where a member conceivably could play with a single sleeve of golf balls for an entire year. The walk is uninterrupted by the ugliness of searching for balls – the magnificent live oak trees draped with Spanish moss and other natural surroundings which frame the fairways enabled Raynor to design 80-90 yard wide corridors in which the game, and the physical environment, may be enjoyed.

The elegant clubhouse is cloaked in a copse of live oaks. Though it is located on a high point, the golfer only sees it on the 1st tee and coming down the 18th fairway. Discretion carries the day at Yeamans Hall.

As noted below, all the classic Macdonald template holes are present. A few might be the best of their sort in the country (Plateau, Narrows, Knoll – long version) but what is more impressive to the author is that all of the templates would be in the top several of their class. From top to bottom, the holes at Yeamans Hall are of an exceptional standard. See if you don’t agree.

Holes to Note

First hole, 425 yards, Plateau; The newly expanded practice green and practice field are snug beside the first tee and the day’s opening drive is across a gentle valley to a 65 yard wide fairway that attractively flows to the right. The sunken dirt entrance road from the gatehouse crosses the fairway 130 yards short of the green. Naturally, golfers have the right of way at all times! Right away, the golfer is exposed to a key design tenet: there is a preferred section within the wide fairway from which to approach the green.

Though the 1st fairway is broad, the approach is better from the right as the Principal’s Nose bunker 70 yards shy of the green obscures views from the left.

The course’s most convoluted green is the 10,890 square foot Plateau found at the 1st. The right side accepts a running shot while the left half sweeps up from the fairway to the first plateau. The golfer above witnessed his approach land several paces onto the green only to have it unceremoniously shunted back well into fairway. The day’s hole location is on the back plateau, which is a prime example of how a large green can require great accuracy.

The Principal’s Nose bunker is evident looking back down the 1st fairway. Obvious too is the day’s fun hole location in the trough between the two plateaus.

Second hole, 375 yards, Leven; With the second a perfect example of the benefit of restoring the greens to their original size, the wise golfer now inquires in the professional shop where the day’s hole location is as it makes a difference off the tee. This green tripled in size (!) from 1997 to 2017 and now stands at 9,468 square feet. Some fascinating hole locations were recovered, especially behind the left front bunker. When the hole is tucked there, the play from the tee is long right on this dogleg to the left. Conversely, if the hole location is middle or right, a hard running hook up the inside left of the fairway is ideal. Before the green restoration project, it mattered not a lick where one placed his tee ball as the green was a small, flat oval pad well removed from the left bunker – no angles were in play. Raynor expert George Bahto suggests the fifth at Piping Rock built in 1912 was an early inspiration to Raynor for this type drive and pitch hole. It is a rare example of where bunkers on the outside of a dogleg work well strategically.

The graceful sweep of the 2nd fairway is made all the more intriguing by three bunkers encased by fairway on the outside of the dogleg paired with a deep left greenside bunker.

Compare this 2005 view of the approach to the 2nd green …

…with this view in 2017. The pines and magnolias are gone as a comforting backdrop and indeed, the flag is now seen on the distant 3rd green.

Third hole, 145 yards, Short; The horseshoe contour in the middle of the Short green must be seen to be believed, but it is clearly marked on Raynor’s plan for this hole. Indeed, Raynor also incorporated the same feature into his Short green at Yale Golf Club but sadly the feature has been gone from Yale’s fifth green for over five decades. The savannah behind the third green at Yeamans Hall makes depth perception difficult but such was not always the case. In Raynor’s day, a wall of trees acted as a backdrop but Hurricane Hugo changed that in 1989. Without doubt, Raynor would prefer today’s hole as the wind is much more of a factor.

Yeamans Hall is one of the few courses in the United States that warrants years of study. One aspect that the golfer learns through trial and error is where to miss the ball around the greens. In the case of the 3rd, the front bunker is half as deep …

Fourth hole, 495 yards, Bottle; The fourth and fifth holes move away from the savannah and play across a rare portion of the property that could be considered flat. Raynor didn’t have the option to continue the fourth along the savannah as that area was reserved for homes (which were never built thanks to the Great Depression). When faced with this flat section, Raynor didn’t undertake superfluous wall-to-wall shaping from tee to green to liven matters but instead concentrated on central hazards and the green complexes. In the case of the fourth, the long central bunker that gives the hole its name was restored in 2007. The green is one of the finest on the course with an attractive false front that is the devil to negotiate. The small spine down the middle of the green adds to the golfer’s worries.

There is no better example of the Club’s unflinching desire to restore all of Raynor’s design features than the reinsertion of the Bottle bunker smack in the middle of the fairway some 220 yards from the green.

As seen from the right rough, chasing a ball up the false front requires fine judgement and is a very satisfying shot to play.

Fifth hole, 420 yards, Alps; Donald Ross had a knack for looking at a topographic map and quickly deciphering high points for greens and tees and then cutting bunkers into up-slopes. Nature spoke and Ross listened with French Lick and Plainfield being thrilling examples. Yet, when given flat land, an architect’s hand is free. He can place his hazards and green wherever he so desires as he isn’t following nature’s lead. In fact, it is incumbent on the architect to lend such holes their golf quality. To understand why the author ranks Raynor among the top half dozen architects of all-time, look no further than this hole. The fairway is a minefield of bunkers and cops and lend this straightaway hole an inordinate amount of character. Raynor only built hazards where they mattered: directly in the line of play and this plays out time and time again at Yeamans Hall. Coupled with the seventeenth, the author has never seen two finer holes on flat land on one course and that speaks volumes as to how well Raynor (a mediocre player himself) understood the game.

… cops along the left need to be avoided as one makes his way down the 5th fairway. Even so, it remains the world’s flatest Alps!

Unusual for a green built in the 1920s, access to the 5th green is completely walled off by a fronting bunker. When Yeamans opened for play in the days of hickory shaft clubs, the 5th measured 400 yards. The approach would have been with a long iron or even a wood, making the carry of the Alps bunker a daunting task.

Compare this black and white photo from 1995 to the one above and one readily gains a sense of just how far this design has come.

Yeamans Hall Club

South Carolina, United States of America

Sixth hole, 185 yards, Redan; A classically manufactured Redan hole and one that stands out for the width of its green complex. No kidding, the line off the tee can vary one day to the next by 30+ yards, something that is unheard of on a one shot hole. As a result, one could merrily sit on the tee with a small bag of balls and try to get the draw just right. The Club wisely allowed Urbina to extend the tee box back another twelve yards in 2003 to force the better player to keep a mid iron in his hand. The ground game aspects of a Redan green complex do not function as well if the player is hitting in too short (i.e. too high) a club.

Yeaman Hall’s attention to detail is admirable: the bunkers 40 yards shy of the putting surface were restored in 2006 and harken back to the short ones at North Berwick.

The early morning light highlights the pronounced kicker slope that dominates the play of the Redan with the thinking golfer using the right to left slope to access back left hole locations.

As at North Berwick, three bunkers guard the rear of the green. The odds of a successful up and down to a green that races away are not in the golfer’s favor. Recovery from the front left bunker is much easier as the golfer can use the slopes to his favor.

Seventh hole, 430 yards, Road; The essence of an approach to any Macdonald/Raynor Road Hole is how one runs the approach shot past the front left Road bunker while avoiding the long bunker along the right that simulates the road at St. Andrews. In this case, like the Road Hole at Piping Rock, the approach is uphill. The fact that is still plays well is a testament to the firm conditions that Riddle provides. As of this writing in December 2017, the author doubts the course has ever played better. A recent round was highlighted by two shots. The first was seeing a bullet approach with a hybrid hit just shy of the Bottle green, climb the false front and onto the putting surface, run, and then scurry off the back and down the tightly mown slope. The second was a crisply struck approach with a mid iron to the Road green that just carried the Road Bunker, the ball then released down the slope of the green which runs away back left and again was dumped off the green. The playing conditions are that pristine and firm at the moment. When asked, Riddle thinks he will be able to maintain the new Bermuda Celebration fairways and Champion G12 greens that firm for years to come.

The 10,000 square foot green is draped on the crest of the hill with the front half facing toward the golfer and the back half running away. Only a precisely judged approach will do given the firmness of the turf.

Eighth hole, 425 yards, Creek; After the fourth, the preponderance of playing corridors is straight on the non-one shot holes. Yet the golfer is unlikely to realize that fact as either the placement of the hazards or the greens or the backdrops greatly vary. Here, this natural hole falls over the property’s most dramatic terrain and impresses as it heads toward the savannah. Several paces beyond the back edge of the 44 yard long green is Goose Creek. The deep green paired with the clean backdrop combine to create depth perception issues and make it difficult to chase after back hole locations with the required conviction. Consequently, this is home to an abnormal amount of three putts. Interestingly enough, the most spectacularly situated green site on the course features the shallowest greenside bunkers.

The attractive lowcountry backdrop to the downhill 8th. On the odd occasion such as with the 15th at Shoreacres, a favorite hole emerges when Raynor broke from building a template and created something original.

The entrance onto the putting surface is at grade with the fairway and sure enough, that means that the greenside bunkers are the most shallow on the course.

Ninth hole, 530 yards, Long; As recently as twenty years ago, there was only one bunker tee to green, thus robbing this three shotter of much playing interest. Four of Raynor’s original five bunkers have been now restored and the golfer needs to negogiate past them to set up a pitch to the built-up green complex. The green features one of the most pronounced north/south spines on the course and the golfer is wise to use its slopes to access perimeter hole locations, rather than flirt on his approach with the deep greenside bunkers. While this isn’t among the course’s best holes, it is among the most improved. Though it may seem counterintuitive to focus on the worst as opposed to the best, one way to judge a course is take a look at its bottom third holes (i.e. your six least favorite holes) and if they are of the standard of Yeamans Hall’s, then you have something special.

As seen above with the ninth tee markers, a fastidious effort has been made over the past several years to return any built-up tees to grade. Removing such artifice only shines the light on the natural environment. The railroad track tee markers pay tribute to the Club founders and how they arrived via train from the North.

The 1st, 7th and 9th tee balls feature the only forced carries on the course, and all of those are under 80 yards. If there is a finer course in the United States on which to learn the game and then enjoy it for life, the author hasn’t seen it.

Tenth hole, 360 yards, Cape; As previously noted, one aspect of the 2017 restoration is the addition of eight acres of fairway, with the tenth hole being a prime beneficiary. Interestingly enough, a non-Raynor bunker was removed left of the fairway and, if anything, the tee shot became harder as errant tee balls left now scamper unimpeded until they find worse trouble than the shallow bunker that was removed. The author paced off the fairway and started laughing less than half way through as he realized he had already covered the distance of many a parkland fairway. Picking the line off the tee is a matter of interpretation and hinges on the day’s hole location. The manner in which the green’s right side rises into a shelf and protrudes into the steep right bunker is how the hole garners its name. Far right hole locations are among the toughest on the course and the approach angle on such days is immeasurably improved by a drive long left. Long time Head Professional Claude Brusse is a big fan and notes, ‘The clearing has opened up more options off the tee and creates more depth perception problems. Yeamans Hall is a course where Raynor wanted you to have multiple lines to the green with risk-reward, also doubt is created when you put yourself on a line to the green where the surface cannot be seen and the depth of the green cannot be determined.’ The tenth embodies those very sentiments.

The 68 yard (!) fairway stretches out of view. The player delights in finding a shortish length two shotter at the start of the second nine as he has just played four difficult two shotters in the past six holes. Yet, don’t let the wide fairway fool you as the green is the smallest target on the course plus it has the fiercest interior contours with a deep horseshoe imprint.

Trees were cleared behind the green and the short iron approach to the 10th holds plenty of interest as…

…deep bunkers left (seen above), right and behind make for a taxing recovery. As with many Raynor designs, the bunkers aren’t so much deep as the green pad is tall.

This golfer’s approach was sucked down into the thumb print indentation. Instead of a short birdie putt, his hands are now full to avoid three putting.

Eleventh hole, 410 yards, Maiden; Yeamans Hall’s trump card over Raynor’s design at nearby Country Club of Charleston is the rolling topography with which Raynor had to work. He made perfect use of it here whereby a forty yard gulley intersects the fairway starting 215 yards from the tee. Tee balls down the left have a clear view of the Maiden green but Raynor’s bunker cut into the far side of the gulley insures that many an approach is blind. The concept of a blind approach in the lowcountry is novel indeed (!) but the hole’s lasting attribute has to be its rolling Maiden green, with its elevated back left and back right sections.

… it is anything but as this view from the gulley indicates. In fact, what a fascinating photograph: the green would be visible had it not been for Raynor’s high bunker wall. This is a prime example of an architect in the Golden Age actually creating a blind shot, something many modern architects are timid to do.

The two approach shots provide radically different putts. The tight turf even looks fast on this winter’s day!

Twelfth hole, 360 yards, Narrows; A drive and pitch hole of exception, to the point that it might be the course’s most underrated hole. Should one lay back from the penal left fairway bunker that pinches in at the 245 yard mark? Or risk a driver to carry past the ridge that the bunker is cut into and thus be on the same level as the green? As part of the 2017 restoration, a non-Raynor bunker was removed from the right side of the fairway which was expanded to once again offer the optimal angle into this angled green. When a club has the fortune to be custodian of a work by one of the all-time master architects, duty falls on it to do the right thing. As it is presented, Yeamans Hall reeks of being authentic to the architect’s intent as opposed to being a hodge-podge of different board’s interpretations based on fads of the time. Augusta National, please take note.

As with the modest length 10th, the fairway is astonishingly wide – and the green complex is equally ornery. At 5,635 square feet, this angled green is second only to the 10th as the smallest target on the course.

This view from near the 13th tee highlights how the 12th green feeds balls into the long back bunker. In addition, this is but one of many instances where the golfer enjoys a short green to tee walk, making Yeamans Hall one of the game’s finest walks.

Yeamans Hall Club

South Carolina, United States of America

Thirteenth hole, 195 yards, Eden; As patterned after the eleventh on the Old Course at St. Andrews, the classic Eden hole is exposed to the elements and enjoys long views beyond the green. In the United States, the eleventh at Fishers Island is preeminent for those reasons. Here, the hole is laid across the property’s high portion, making it well exposed to whatever wind is about. As part of Yeamans’ relentless march to do the right thing, small pines and brush behind the green were removed, exposing more long views to the savannah as well as increasing the wind’s impact. Relative to other Edens, a differentiator here is another of those wonderfully soft north/south spines. Consequently, the hole is rarely in the middle section of this wide green. Yet, to drop a ball into the Hill bunker left or the Strath bunker right is to not understand the opportunity that the architect affords at the green to work a fade or a draw off the spine. Shaping shots like this tee ball or a draw off the second tee, a power fade at the fourth, a drawn approach at the seventh, etc. remains an art form at Yeamans.

Though a great admirer of the Eden at St. Andrews, C.B. Macdonald felt the hole had one weakness and that was that the golfer could putt the ball from tee to green. Thus, bunkers were placed short of the green complexes on many of his, and subsequently Raynor’s, adaptations of the hole. True to Raynor’s original design, these short bunkers were restored in 2004.

Fourteenth hole, 410 yards, Knoll; A ridge confronts the golfer in the tee ball landing area, insuring that a level stance is rare as well as robbing the ball of needed run. This is unsettling because the approach shot is the course’s single most intimidating shot. More dirt was moved in the creation of this green pad than on any other. The result is striking, with a twelve-foot deep bunker diagonally across the left and a seven foot deep bunker down the right. More than a few members consider this to be not only the course’s best hole but also the finest hole in the Palmetto State, which is saying something for a state with the Ocean Course at Kiawah and Harbour Town. Named Knoll, its length has increased thirty yards since Raynor’s day. Most Knoll holes are short, so Bahto considered this to be a standalone long version of a Knoll.

The 14th plays across two valleys, a shallow one off the tee and a more pronounced one for the approach thanks to the massive amount of dirt that Raynor pushed up starting forty yards shy of the putting surface.

Fifteenth hole, 450 yards, Lido; As explained in George Bahto’s Feature Interview , the Lido, also referred to as Raynor’s Prize Dog-Leg, is often the hardest two shotter on a course, so when it is sandwiched between the bruising Knoll (long version) and a Biarritz, the player’s mettle is sure to be tested. A friend of no man, the hole’s length generally means that most pars are the result of a one putt. If the drive doesn’t find the fairway, just clearing the two central hazards that now wall off the fairway 80 yards shy of the green becomes problematic. Urbina’s installation of these bunkers in 2017 was among the last central hazards that begged to be returned to their former glory. For decades, it was felt the hole was difficult enough without them and certainly, a weak Green Committee wouldn’t have the constitution to proceed. Yet, to think that golfers playing with hickories cracked on with such central hazards in place while modern players whinge is surely a poor testament of the modern golfer. It probably highlights too the difference between beating your mate in match play versus today’s fixation with medal play. Up ahead, the underrated hog’s back green is the final ‘salt in the wound’ to prevent the desired score.

Sixteenth hole, 225 yards, Biarritz; The original intent of a Biarritz green design was to allow the golfer to hit a low running three wood, see the ball disappear in the trough, and then reappear on the green. There is no denying the fun derived from such a well executed shot. To have the word ‘fun’ linked to such a long one shotter is a tribute to the lasting merit of the Biarritz design. The sixteenth at Yeamans enjoys one attribute that other Raynor Biarritz holes are losing with the march of technology, namely the ability to continue to lengthen it so that Raynor’s desire for the golfer to play a fairway wood into a green can be preserved. Several other of his Biarritz holes are ‘stuck’ in the 200 yard range, merely a mid iron for a low marker today. There is a good thirty yards back toward the fifteenth green that the Club can utilize, should it so desire, which would even reduce the green-to-tee walk.

Seventeenth hole, 420 yards, Punchbowl; The start of a perfect finish, with the harder hole being the penultimate one. The punchbowl green is deeply bunkered front left, along the right and behind, leaving one to marvel as to how Raynor created such depth on relatively flat land without seemingly disturbing the surrounds. As seen below, the hole is littered with hazards from tee to green and they all interconnect and play off each other. As such, a game at Yeamans distills into a chess match with Raynor.

… a distinctly more complicated approach thanks to Urbina’s recent bunker work. With the restored front left bunker once again flush against the putting surface and its wall of appropriate height, it combines with …

… the deep back wrap around bunker to provide a true Punchbowl effect. The irony of both an Alps and a Punchbowl on flattish ground is rich. It certainly shows Raynor’s inventiveness at interpreting Macdonald’s design concepts.

Eighteenth hole, 530 yards, Home; A reachable three shotter (e.g. Pebble Beach, Castle Stuart) or a drivable two shotter (e.g. Durban, The Old Course) are magnificent ways for a course to conclude as anything from an eagle to a double bogey awaits. The author thinks the one at Yeamans is ‘on par’ with those four mentioned and sure enough, this is my favorite hole on the course. The extended tee area coupled with the restored serpentine bunkers at the sixty yard mark from the green dictate prudent tactics. The last hundred and twenty yards feed down into a natural amphitheater where the golfer is surrounded by azaleas, live oaks and the white clapboard cottages near the clubhouse. Meanwhile, the high back left to lower front right slope on the green is appropriately the most severe on the course, and the match is not over until that final ticklish putt drops. This finish – charming, thoughtful, and well laid out – is the kind that the course deserves. Interestingly enough, Raynor originally had it as a long two shotter from the forward tee. Going back to the fourteenth, and playing the eighteenth as a two shotter, these five holes comprise the most difficult stretch of holes that the author has seen on any Raynor course. Indeed, though ‘charming’ is the word most closely associated with Yeamans Hall, Bahto considered this course to be among Raynor’s three ‘toughest’ designs when the courses originally opened for play (the other two being Chicago Golf Club with its relentlessly deep bunkers and Yale Golf Club with its heaving, rocky topography).

One of the most heavily bunkered areas on the course is the last 130 yards of the Home hole. It is rare indeed to find a second shot on a three shotter of equal interest.

There you go – Beethoven would be proud of the four movements. Here’s the thing: with a symphony, a single artist creates a composition and demands it be played as the notes prescribed on the sheets. Raynor could never have envisaged the Great Depression nor the outrageous improvements in agronomy. Raynor’s only thought was that his course was one ‘movement’, i.e. his original work. And yet, as Yeamans Halls exists today, surely he would celebrate the joy that his work of art brings to all. It is the best it has ever been.

Very few clubs possess the understanding and can muster the conviction to enter into the all important fourth movement. The famed line from Lampedusa’s The Leopard comes to mind: ‘If we want things to stay as they are, things will have to change.’ By the early 2000s, the Club had gained a clear sense of how good the course had become yet knew what remained. The absurd four feet of rain that fell in the fall of 2015 helped set the stage for the final push for it was in this fourth movement that the most controversial features were dealt. In the case of Yeamans Hall, there was tree and branch removal as well as the insertion of central bunkers in the positively most annoying, confrontational places. Coupled with the agronomic improvements, Yeamans Hall is simultaneously more fun (wider playing corridors, loads more short grass) and more difficult (firm playing surfaces, who put a bunker there?!). What a neat trick that is. If ever one wishes to know why Golden Age courses are put on a pedestal, come study here as it strikes the perfect balance of enjoyment and challenge for all.

Everyone is sitting up and taking notice as to the attention of detail in how Yeamans Hall is being presented.

Appreciating what an important time this is in the evolution of the course, member Charlton deSaussure has penned a nearly 100 page book titled The Golf Course and Grounds of Yeamans Hall that will be published in 2018. He traces the founding of the Club and the progression of the course. In a book full of fascinating insight and lines, one of the best is at the very start. A key driver to the formation of the Club was Thomas Lamont, who followed J.P. Morgan Jr. as the Chairman of Morgan Bank in 1943. deSaussure’s research reveals, ‘Upon his death in 1948, The New York Times wrote of Tom Lamont’s “unremitting search for the good, the full and the gracious life.”‘ If any line – the good, the full and the gracious life – can accurately convey a sense for a place, that’s the one.

Yeamans Hall’s clean scorecard reads, ‘Yeamans Hall Club, Charleston, South Carolina, Seth Raynor, Designer, 1925.’ Raynor himself best summed up its virtues in 1925 when he wrote, ‘I would say this course is going to combine the sandy seaside features and the rolling dune effects so desirable in the coastal area. The fairways are made beautiful by the magnificent live oaks and large pines bordering them. The encircling trees give a warmth to the course in the wintertime which is very delightful. This, combined with the invigorating climate and all the other fine features this spot contains, is bound to make one fall in love with golf at Yeamans Hall.’ Those sentiments have never been more true than they are today. Raynor’s vision has been comprehensively reinstated on playing surfaces that are firmer, faster and more uniform than anything the Maestro could have envisaged.

The founders of Yeamans Hall saw the potential to expand upon an environment that would delight the senses. Time has proven their vision correct and over the past thirty years, the Club has elevated the course to possess an appeal every bit as timeless as that of the lowcountry itself.

![The Park, West Palm (Lit 9) [2023]](https://golfclubatlas.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/IMG_7092-2-scaled-500x383.jpg)