Yale University Golf Course

Connecticut, United States of America

Inland golf’s only near equivalent for drama to the sixteenth at Cypress Point is the awe-inspiring ninth at Yale.

How well does an architect’s work stand the test of time? In the case of Seth Raynor, there is something uniquely appealing about his engineered style and many of his courses have withstood the time test. Shoreacres, Fishers Island, and Chicago Golf Club play largely as he intended. Recent restoration work at Yeamans Hall, Lookout Mountain, Camargo, The Creek, Mountain Lake, Country Club of Fairfield,and Country Club of Charleston have returned many of the best design features to those designs as well. Despite the overall excellence of these designs, Raynor’s work at Yale University may be fairly considered his monumental achievement.

Set on 700 acres (!), Seth Raynor incorporated the lakes, ponds, hills, mountains, and rock outcroppings to create a course of such massive scale as to make most courses seem puny. The holes are big and burly with fairways that range to sixty yards in width and several greens greater than 10,000 square feet in size. The bunkers are deep and deeper with some requiring flights of steps and the contouring of the greens is unsurpassed in the United States for boldness. When Yale University opened for play in the autumn of 1926, it was the most expensive course built to date as the result of working with the rocky, hilly New England land. Given the severe terrain, the course was going to be a hit or miss – the architect would either get it right and create holes that would never be duplicated elsewhere or he would get it wrong and forever be fighting the land.

Thanks to Raynor’s superior routing skills, and with input from C.B. Macdonald on the advisory committee, the end result is an original all the way with none of the holes reminding the golfer of those from other courses. There is no hint or whiff of blandness; nor is there any sameness that plagues fine but not great courses. For boldness of vision and construction execution, it ranks right there with other such monuments of design as Pine Valley, Oakmont, and Macdonald’s own National Golf Links of America. However, to be clear, it is Raynor and not Macdonald that deserves the credit for the design at Yale University. As proof, George Bahto, the world’s leading Macdonald/Raynor historian,frequently points to an article from Charles ‘Steam Shovel’ Banks, who worked on the Yale University construction team. The article appeared in an Alumnae Bulletin in 1929 where Banks wrote that Raynor deserved credit for ‘what is today considered by many to be the outstanding inland golf course of America.’ Banks went on, ‘Mr. Macdonald, who served on the advisory committee, was familiar with the plans from the outset, but Raynor was the real genius of this masterpiece, who made the layout, designed the greens, and gave the work of construction his supervision from start to finish.’ Not exactly an ordinary putting green – notice the depth of the swale in the middle of the one-of-a-kind ninth green relative to the flagstick!”

Starting in 2003 with the hiring of Scott Ramsey as the new Green Keeper, diligent work has been performed to reverse several decades of neglect. Ramsey immediately started to set the stage for better turf conditions by overseeing a significant tree clear program that saw over three thousand trees felled. Long views were opened up within the interior of the course.Playing corridors were expanded at the second, seventh, tenth, eleventh, twelfth, fourteenth and eighteenth holes. Trees were cleared around such greens as the sixth and thirteenth to improve airflow and circulation. With the trees gone, attention was turned to improving the fairway drainage, with particular beneficiaries being the fourth, sixth, seventh and eleventh fairways. In addition, right from the start, Ramsey focused on getting the fairway and green mowing patterns correct. He was able to recover lost putting surfaces at every hole with as much or more than1,000 square feet (!) being restored at the first, second, ninth, twelfth, and seventeenth greens. In addition, the steep pitch of the Eden green was recaptured, allowing it to once again function properly. The end result of all this hard work is that conditions are now set for better turf to follow. Once the turf quality begins to match the excellence of the design as we see in the Holes to Note section below, Yale University will once again be viewed as a course with few peers.

Long views have been opened up such as this eight hundred yard one from behind the second green all the way up to the seventh green on the right.

Holes to Note

First hole, 410 yards, Eli; The adventure begins right away with one of the most intimidating opening shots in American golf. From a tee high above Griest Pond (the name comes from the 700 acre Griest Estate which Mrs. Ray Tompkins gave to Yale University in 1924), the golfer feels dwarfed by his surrounds. Everything is on a scale: the elevation changes, the forced carry, the wide fairway, the huge green, and the deep greenside bunkers. A mid iron approach may well see the golfer onto the green. A snap hooked mid iron might also see the golfer onto this massive 10,300 square foot green as well! Its contouring looks like nothing more so than a heaving sea with a ridge dividing the green left into a punchbowl and right into a higher plateau. This arrangement with the spine running from back to front through the middle is far more appealing than the modern, common place version where the spine runs left to right.

Especially remembering that Yale was built in the days of hickory golf, such a start with a forced carry over Griest Pond signifies that Yale was always designed to be a brawny challenge, reflective of its rugged surrounds.

Second hole, 375 yards, The Pits; Bahto has discovered that two rather large mounds were removed from the middle right of the putting green in order to promote ‘more accurate putting.’ Unfortunately, the well-meaning individual who drove this change did not understand how those mounds could be used by the golfer to help work the ball over to the tricky left hole locations. On the bright side, Ramsey has expanded the existing green in the front and especially along the left side, thus creating some terrifying hole locations overlooking the cavernous bunkers. Despite the bunkers having been tinkered with by a professional golf architect who didn’t demonstrate an understanding of Raynor’s engineered design style, the hole’s inherent quality still shines through.

Even back on the tee, the steps that lead down into two pit bunkers that guard the left of the green are evident. This is the golfer’s first exposure to steps leading into/out of bunkers and it won’t be his last.

A true Cape hole features a green that juts out, and the second fits that bill as well as any.

Third hole, 410 yards, Blind; A fine strategic hole as the closer one drives to the pond on the right, the less of the hill one must carry on one’s approach and the better the angle. Unfortunately, when Raynor’s original double punchbowl green was moved away from the pond to its current position,the replacement green built lacked the same imagination that Raynor enthused into all the other greens. The two most exciting projects upon which Yale University Golf Club could presently embark would be to restore Raynor’s double punchbowl green here at the third as well as to return the sixteenth green complex to Raynor’s original location.

Drives that flirt with the water down the right leave an easier approach over the hillock to a hidden green marked by the distant Yale flag.

This view is from the top of the hillock that makes most approach shots blind. The circular green itself is bland, especially by Yale’s own high standard.

As seen here during construction, Raynor’s green was twenty yards to the right and was twice as big with a punchbowl section that extended close to the pond on the golfer’s right. The incentive to hug the water off the tee was greater as right hole locations could be seen from the right portion of the fairway.

This view from the fourth tee shows the direction marker behind the current third green.

Fourth hole, 435 yards, Road; One of Ben Crenshaw’s favorite holes in golf marks the end to an all-world start. National Golf Links of America and Chicago are clear indications that Macdonald enjoyed starting his courses with the very best holes and perhaps Macdonald’s influence as an advisor to Raynor at Yale University can be seen in this regard. Raynor used the pond to re-create the angle of the out of bounds at the famous Road Hole at St. Andrews and created a Road bunker twice as deep as the one in Scotland.

The shorter reeds in the distance in this view from the fourth tee show where the lake intrudes back into the fairway, forcing golfers to steer left.

However, as this view from the fairway indicates, the Road green is actually a mirror image one, meaning that the golfer doesn’t mind coming in from the left portion of the fairway. Why was the green built on a left to right angle as opposed to the normal right to left one? Simple – the rock beneath the green site didn’t allow it.

Fifth hole, 145 yards, Short; Yale University’s recent tree clearing program greatly helped all four of its par threes. Here at the fifth, the built-up green once again seems isolated in a sea of sand. Nonetheless, photographs from the 1930s show that the front bunkers were once nearly twice as deep, requiring eleven steps from which to climb out. Also, the typical bold interior green contours found within Raynor’s best short holes aren’t in evidence here.

Though not as demanding as in the past, the fifth remains an attractive Short hole with its ‘hit it or else’ green.

Sixth hole,420 yards, Burnside; Though one of the less dramatic holes on the property, it is a fine example of Raynor’s command of angles, an attribute of which Pete Dye much admired and later emulated. A stream dominates the inside of this dog leg left and by the green, a large, rustic bunker once protected the full length of the green’s right side and extended well into the fairway. If the golfer successfully flirted with the creek, he had an uninterrupted view down the length of the green. If he bailed to the right on his tee shot, the resulting approach shot was more complicated as it had to carry this menacing bunker while at the same time coming at the green from an awkward angle. Unfortunately,the current right hand bunker is the single worst (i.e. poorly constructed and aesthetically out of place) bunker on the course. Until it is properly rebuilt, the strategic principles of this Leven hole are undermined.

Seventh hole, 375 yards, Lane; Raynor’s engineering skills were invaluable during the construction of Yale University and he used dynamite to great effect in the creation of the seventh and fourteenth fairways. Without the selective use of dynamite to create what would become the seventh fairway, the eighth and ninth holes might never have been built. As it is, the seventh fairway appears natural and unforced and the hole is capped off by a mammoth green which features nearly five feet of drop from its back to front as well as fascinating interior contours. All told, this green may well elicit more three putts than any other one on the course. Given its myriad of interesting hole locations, the golfer appreciates one of the reasons why Yale members never tire of playing their course.

The tall rock mound on the right extended across today’s seventh playing corridor when Raynor first walked the property, necessitating the need to use dynamite to create room for the seventh fairway.

Eighth hole, 410 yards, Cape; Bending left around a natural fall-off, the eighth is a world class hole that fails to get its due because of the large shadow cast by the ninth. Nonetheless, it remains the favorite of many a member in part because of all the ways that the hole plays throughout the year. Though the fairway is plenty wide, the approach is often times blind, unless the golfer places his drive in a precise area in the right center of the fairway. Of course, downwind and the same landform that can make approach shots blind can be used to chase a tiger golfer’s tee ball within forty yards of the putting surface. Conversely, when played into a stiff breeze off Long Island Sound,even the tiger is left with nearly a two hundred approach shot. Regardless of where one’s drive finishes, the approach is a delight as the golfer tries to avoid the deep greenside bunkers on either side (how deep? the bunker on the right is twelve feet deep and is the shallower of the two) while using the severely sloping Redan green to chase balls toward various hole locations. The eighth green complex embodies the concept of using the ground to get from point A to point B as is so often found in the United Kingdom. The American version of aerial golf of hitting and finishing at point A is infinitely less interesting/compelling.

Though the left greenside bunker is clearly a fearsome hazard, Raynor gives the golfer plenty of room to avoid it by playing to the right and…

…using this Redan kick board to sweep balls deep onto the putting surface.

The rolling nature of the eighth fairway is evident in this view from behind the green. Gauging where best to land one’s approach never gets tiring. For instance, this forward hole location calls for a shot that lands short of the green and then feeds left toward the hole. A back hole location could require four more clubs (!) into this forty-six yard deep green.

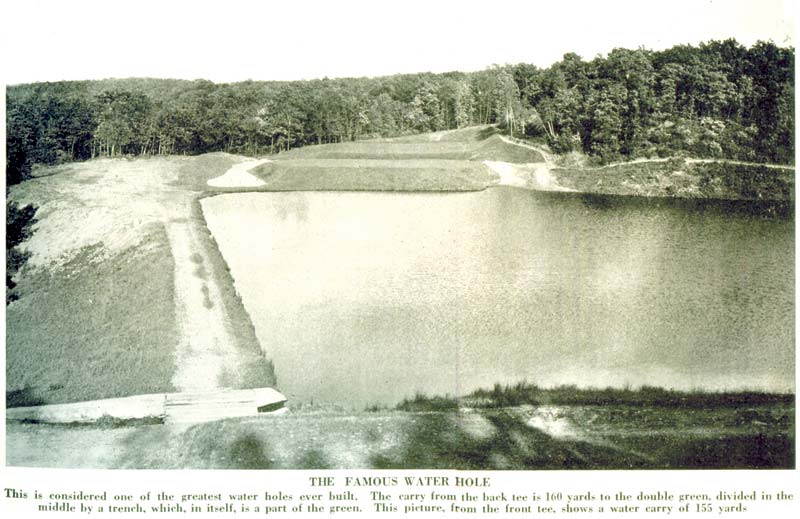

Ninth hole, 215 yards, Biarritz; The author’s favorite inland one shotter, the view from the tee will stay with the golfer until his dying days. The feeling one gets playing the hole the first several times is that of standing on a precipice hitting over an abyss to a green that is impossibly far away. The reality is only slightly more on a human scale with tee perched high on an embankment sixty feet above Griest Pond. On the far side of the hundred yard wide pond is one of the world’s largest single putting surfaces, measuring sixty-five yards from front to back and including a five-foot gully (!) through its middle. The sheer audacity of this 12,000 square foot green sets the hole apart in world golf as, after all, no further dramatics were really required given the heroic nature of the tee ball. In theory, the player is to use the front slope of the gully to help sling the ball to the back hole locations. Thus,as with every full length Biarritz, it should be mandatory that the hole be placed on the back half of the green the vast majority of the time as the tee ball is more varied and interesting. Indeed, when the hole is forward, and given the downhill nature of the hole, the tee ball is often struck with little more than a mid-iron. This robs the hole a tad of the excitement that must have been present in the days of hickory golf clubs when a five wood or long iron was required.

The golfer whose tee ball finds the rear portion of the green is left with this putt through the swale when the hole is forward – the ball literally disappears from sight during the course of the putt! The elevated tee is on the far ledge.

Yale University Golf Course

CT, USA

Tenth hole, 395 yards, Carries; Given the obvious difficulties of the fourth, eighth and ninth holes, one might be surprised to hear that many members consider this sub-400 yard hole to be the hardest par on the course. Despite the hole’s tee to green defenses, it is the violent green itself that leads many a critic to conclude that a more challenging uphill approach shot has not been built since Yale opened. Only the uphill approach to the second at Pine Valley compares.

If the golfer clears this embankment off the tenth tee, …

… he is faced with this steeply uphill approach shot. Two deep bunkers are at the base of the green complex, from which the dozen plus wood steps ascend.

Yale calls for a fascinating mix of aerial and running approach shots. The tenth green complex certainly calls for the former!

An ingenious putting surface, an approach putt from the back right corner can be played into a slot near where the flag’s shadow is and come to rest close to this front right hole location, having traveled more than twice the distance as the direct line.

Eleventh hole, 380 yards, Valley; The tenth through twelfth holes are laid over the most rambunctious portion of the property. The tenth is a roller coaster ride unto itself and it brings you to the eleventh tee, which is the high spot on the property. Aptly named, one’s tee ball must find the fairway in the valley some sixty feet below. Given the length of today’s technology, the mirror image Redan playing characteristics of the green are perhaps even more maddening than in Raynor’s day. Today’s tiger might be left with a fiddly fifty yard pitch over a deep front bunker to a green that runs away. Such a conundrum has riddled golfers at The Old Course at St. Andrews for years.

The exhilarating view from the elevated eleventh tee captures some of the rugged charm of the New England landscape including the granite face below which Raynor placed the left fairway bunker. Drives in the valley near there leave the best angle into the long green.

In all of world golf, there are not four greens with more spectacular interior contours than the ones found from the seventh through the tenth at Yale. As a follow-on to those four, Raynor wisely opted for a more subtle green here at the eleventh. However, don’t be fooled: its high front to lower back tilt has its own bedeviling playing qualities.

Twelfth hole, 400 yards, Alps; Since Green Keeper Scott Ramsey’s arrival and since Yale started spending the appropriate care and attention on this treasure of a golf course, this is the single most improved hole. Roger Rulewich did a fine job in re-creating the deep Alps bunker in front of the green and in rebuilding the bank before it. Set across tumbling land, this is one of the three or four finest Alps holes in play today.

This view from behind the Alps green hints at the recently restored deep bunker that now fronts it. Before Rulewich’s work, two small bunkers of no consequence were in front of the green.

Thirteenth hole, 210 yards, Redan; Though a striking Redan with postcard qualities, its playing characteristics are somewhat diminished because the hole is both downhill and Yale struggles to present firm and fast playing at this sheltered green. Thus, the needed release of a tee ball from right to left across the green that makes any Redan hole great is often times found wanting here. If anything, on a downhill Redan, the green slopes need to be more pronounced than usual given the steep descent of the tee ball. Here, the slope and right kick board are too muted. Given the boldness of the Redan green at the eighth, the author would not be surprised to learn that this green has been softened/tinkered with over the years.

If the thirteenth enjoyed firm playing conditions (and the damn cart path were relocated!), watching a tee ball play out and roll right to left across its huge putting surface would be one of the most rewarding shots on the course.

This view from forty yards short hints as to how relatively flat this Redan green is and that it doesn’t possess a sufficient right to left cant.

Fourteenth hole, 365 yards, Knoll; A first rate bunkerless Knoll hole, Raynor constructed the right side of the fairway to be considerably lower than the left, allowing the golfer to sling a power fade off this created bank to propel a tee ball closer to the green. A short iron approach is quite handy as this relatively small, firm green is a tough target to hold from a hanging lie well back in the fairway.

This famous wood carving was once three rows of trees deep into the right woods. Now it can be seen from the fairway as the golfer walks past.

The elusive built-up fourteenth green seems tiny relative to many of Yale’s greens and that’s because it is. At twenty-four yards in depth, it is easily the shallowest target on the course.

A view from the fourteenth green back down the fairway shows the bank in the fairway that Raynor created.

Fifteenth hole, 190 yards, Eden; Many of the greens have been enlarged and returned to their full size under the initial work accomplished by Ramsey. One of the most successful such instances occurred here where twelve feet of putting surface was recovered along the back and left. Now the green enjoys a ferocious amount of back to front tilt in keeping with the original Eden hole at St. Andrews.

The view from the tee shows how much of the left and back slope of the Eden green has been recaptured. Beforehand, the green was nearly a flat oval devoid of much playing interest.

Sixteenth hole, 555 yards, Lang; A tale of two halves. The drive is one of the more interesting ones on the course as the golfer tries to play a draw off a pronounced landform in the right middle of the fairway to get a forward kick. If successful, the green is within reach on one’s second. Unfortunately, the last fifty yards of the hole is deadly dull, especially compared to all that has gone before. The primary reason for this let down is that Raynor’s green was moved thirty yards back and to the right from its original location. No one is clear who or when the work was done and the merit of the work is confined to placing the green site on higher ground. Raynor’s original green ringed by three bunkers was near a low-lying that time proved was prone to flooding and drainage issues. Hence, restoring Raynor’s green location is perhaps not practical. However, by all means, more thought and attention needs to be given to the last fifty yards of the sixteenth. At a minimum, the green complex should be made to look like it belongs on a Raynor course. Perhaps a proper Road Hole green that plays from right to left would fit nicely onto the existing site? Indeed, though Yale was built in the age of hickory golf clubs, technology has moved on and the variety of the course would benefit from picking up a long hard two shot hole on the back nine. As it presently stands,the seventeenth is the only two shotter on the back over 400 yards. Played from Raynor’s tees to today’s green yields a hole in the 475 yard range,a type half par hole that the course doesn’t presently have. In so doing, some will howl that would make the par 69 but the course from the regular tees was in fact a par 69 in Raynor’s day.

Seventeenth hole, 435 yards, Nose; Though the golfer only has two holes to go, he still has well in excess of 1,000 yards to play. This two shotter enjoys a Principal’s Nose feature sixty yards short of the green and one of Raynor’s favorite green complexes – the Double Plateau. C.B. Macdonald, Raynor’s mentor and a consultant here at Yale, first employed this combination of bunker and green complex at National Golf Links of America in 1909. The original purpose of the Principal’s Nose bunker at the sixteenth at The Old Course at St. Andrews was to create two different playing corridors off that tee. Raynor never went to St. Andrews and thus never observed for himself the bunker’s original purpose. Hence, he blindly reproduced the Principal Nose bunker and Double Plateau green as per NGLA at many of his subsequent designs. As at Yeamans Hall, the Principal Nose bunker complex here provides visual deception for approach shots as opposed to providing strategy off the tee.

Though the ridge has been lowered some nine feet since Raynor’s death, the sharply uphill tee ball remains full of challenge.

From back in the fairway, the Principal’s Nose bunker complex obscures half of the high left plateau of the putting green. Getting an approach shot to chase to the far back hole locations is an art form.

As seen from behind, the seventeenth green features a high left and back plateau. To best access this day’s lower forward hole location, the golfer needs to drop his approach shot past the Principal’s Nose bunker complex and have it roll near this hole location.

Eighteenth hole, 620 yards, Home; Though controversial, this sprawling three shotter is the perfectly impossible ending for this innovative design. It is difficult to describe other than to say the hole plays over and around a mountain. For the past several decades, the alternate lower right path was effectively not an option as tree growth had narrowed the right fairway to under fifteen yards in width. According to Ramsey, the right fairway was ”…was 8-10 yards wide from the hill to the tree in 2003. Now it is 21 yards of fairway and 8-10 yards of rough to the tree line. We continue to incrementally recapture more fairway from the rough as we improve irrigation and drainage. Hopefully, we can get to 25-30 yards of fairway and continue to make it a really viable option.’ This course richly deserves a unique ending and this hole delivers like few Home holes. Indeed, the author puts it forward as the best Long hole that either Raynor or Macdonald built due to its originality as well as its optional playing routes (i.e. for the same reasons that the fourteenth at the Old Course at St. Andrews is a standout).

Step one off the tee is to slot one’s tee ball between the near ridge on the right and the far left one. A good drive allows the golfer to scale the hill in the background and take the short route home.

This view from behind the green shows the alternative routes of Yale’s Long hole with the shortest way being to come in from the high side of the fairway (i.e. above the white Yale flag). However, options now abound thanks to the excellent tree clearing work down the golfer’s right of the hole.

Much work has been accomplished at Yale since 2003 and much work remains. However, the golfer of today is once again keenly aware that he is playing a very special course with Yale being a rare example of an architect successfully working with severe terrain. Raynor struck an exciting balance between challenge and fun in part by ensuring that the landing areas and the green targets were ample. Indeed, one of the course’s principle defenses is similar to that of the Old Course at St. Andrews: the size and the contouring of the greens mean that the better golfer may well hit fifteen greens in regulation but suffer thirty-six plus putts to retard a good score. Depth perception becomes difficult when the golfer needs to carry a ball forty yards deep (!) into a green just to begin to get near a back hole location. The challenge of getting an approach close to a hole on a massive green has never dimmed at St. Andrews and the United Statesequivalent is found here at Yale. And remember: nobody, including professionals, practices one hundred foot putts.

Like St. Andrews, Yale reminds the golfer of no other course. To call Yale the best university course in the country is to do it an injustice. Yale remains to this day a colossus in design and a landmark achievement. Congratulations to the University for beginning to realize this and for starting to maintain and present it in the manner in which it deserves.

The author wishes to acknowledge and thank Dr. Geoffrey Childs for his photographs and contribution to this course profile.

The End

![The Park, West Palm (Lit 9) [2023]](https://golfclubatlas.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/IMG_7092-2-scaled-500x383.jpg)