Wolf Point Ranch

Texas, United States of America

Big budget courses open all the time to great fanfare. Why? Because the owners pay for the kind words and publicity! In the steady rollout of such expensive operations, the message was seared into the collective golfing psyche that great golf is expensive golf. Yet, nothing is further from the truth. In 2008, a course opened in southeast Texas. No one knew. Why? Because it was built for a rancher on his property to enjoy with his friends. No fanfare, no pomp and circumstance. Rather, here’s the kind of golf that stirs emotions and makes you glad that you actually play the sport. For those reasons, the lessons about its design and how it is presented on a daily basis are as powerful and as important to understand as any course opened this century. In all respects, Wolf Point represents ‘the back to the future’ of golf. The shame is that it flies so low under the radar while designs of “excess” garner great attention. Only if more ‘Wolf Points’ emerge will the game expand on a healthy, sustainable basis.

The tale starts in late 2005 when Houston-based golf architect Mike Nuzzo fielded a call from a rancher a few hours south who wanted to build his own private course near Carancahua Bay. The potential client’s desires were straightforward. He wanted a challenging and interesting layout on which searching for errant shots was rare. He intended to have his new home integrated with the course so that it would be afforded beautiful views of both the golf and property. After being forced to evacuate during Hurricane Rita, the Gulf of Mexico’s most intense tropical cyclone with 177 mph wind speeds, his home needed to be 20 feet higher than a hundred-year storm surge. Within those parameters Nuzzo was free to create eighteen holes.

After examining several of the rancher’s land holdings, they settled on the central portion of the main 1300 acre parcel that sprawled among the Texas scrub. The high to low point was a mere seven feet, so topography wasn’t a driving force. Instead, live oaks and Keller Creek were the dominant natural features. Nuzzo first focused his attention on the thousand yard Keller Creek that bisected this portion of the property and it eventually became the genesis for eight holes. This meandering stream affects shots in every manner possible from threatening drives at the 16th and 17th to approaches into the one shot 6th and par 5 14th. Nuzzo also created a 13 acre lake which generated fill to augment ground contours as well as to build the hillock for the residence.

The project cost was $3,000,000, of which $900,000 went toward irrigation. Construction took eighteen months. A phenomenon mid-way through the project occurred when a record 24 inches of rain fell in July 2007 right before grassing commenced. While some finished work was ruined, elsewhere anomalies arose. Intense rainfall transformed the 11th green and pronounced irregularities appeared on the sides of the turtleback green. Rather than rebuild, these permutations were slightly refined to make the green ‘mowable.’ Nuzzo loved the result and how nature had ‘melted’ his design.

To add playing interest to the relatively featureless landscape, 60 bunkers made their way into the final design. Breaking down their placement is fascinating and is the modern day equivalent of understanding a design like Woking Golf Club where ‘less is more.’ Nearly ½ of them can rightly be deemed central bunkers (i.e. they are completely encased by fairway). Half of the greens (1, 4, 5, 6, 10, 11, 13, 15, and 17) are without a bunker within 10 yards of the putting surface. Three holes (6, 10 and 15) are bunkerless. Two conclusions: of all the courses in North America which the author is familiar Wolf Point has the highest percentage of fairway bunkers and also features the lowest percentage of greenside bunkers of any top tier course. As a result, a typical round yields more lengthy fairway bunker shots than greenside splash recovery shots. The author can’t think of another course where that statement is true.

Liberal recovery options exist from the tight Bermuda 419 grass that surrounds most of the greens. In the finest links tradition, the pitch and run is crucial for success here. Overall, the putting surfaces are an eclectic set that defy stereotype. Some are canted to the side (the 4th, 6th, 10th, 16th), others to the rear (3rd, 12th and 13th), a few are high in the middle (the 1st, 2nd), while some rise up from grade to four or five feet at the rear (11th, 17th). Still, others possess swales (the 8th, 14th, 15th, 18th). In Volume 2 of The Confidential Guide, Tom Doak called them ‘the best set of greens in Texas.’

As seen from behind, the 4th green is sharply canted left to right but the short grass all around gives the golfer plenty of options.

Of course, such intelligent use of hazards and green contours lose their meaning if the playing conditions are soft with little roll. Enter Don Mahaffey, who Nuzzo immediately engaged in the project once it was greenlighted. Mahaffey managed construction and then stayed on as Greenkeeper. Having long railed against the excesses of American greenkeeping from over-watering to maintaining things that don’t impact the golf, Mahaffey finally had the perfect opportunity (i.e. the right owner, design, climate and soil conditions) to demonstrate his maintenance ideals. With a crew that ranges from 3 to 5 people and an annual spend that averages under $500,000 for the golf course, Mahaffey has overseen Wolf Point’s presentation for eight years. He expresses his thoughts about the luxury of being at Wolf Point and his ideals of greenkeeping:

Wolf Point definitely has some built in maintenance advantages as we only have about 1,000 rounds a year. Less traffic means less compaction from carts. No shotguns, tournaments, or full tee sheets mean we can get by with fewer employees. Yet, what separates us from most courses is we do not do anything extra to make the course “pretty”. A cattle ranch in our part of the world has a rugged appearance and we want that same look for our course; we find a lot of beauty in the natural hues our course offers vs a course that is managed to look evenly green. Every maintenance task we do is based on answering one question, ‘Does it make the golf better?’ Obviously mowing does, as do regular cultural tasks like vertical mowing or aerification. But we never irrigate or fertilize unless we have a good reason.

In terms of how he and his crew routinely achieve firm and bouncy conditions through the green, Mahaffey writes,

Another big advantage we enjoy is that my entire staff was here during construction and I managed the construction and made the agronomic decisions like how the greens were built. We wanted the ball to react exactly the same if it hit two yards short of the green or two yards onto the green. Many golfers say they want this, but what they usually do is use the green construction method out into the approach/fairway areas at great expense. We did the opposite, we brought the approach and fairway soil conditions into the green. We made this decision because we knew we would have limited golf traffic and we knew we want sloped greens with great surface drainage. Thus, we were OK with a push-up style of construction. We have good conditions for golf because that is all we care about, the playing of the game itself, and we have a client that encourages this approach. Having nothing to sell like lots, outings, tee times or memberships, and only focusing on that which makes the game more fun is why we have what we have.

While Mahaffey’s approach dangerously resembles nothing more than common sense, tragically, his approach to green keeping is the exception rather than the rule. Adam Lawrence, consultant and Editor of Golf Course Architecture magazine, is as well traveled as anyone in world golf. Having been to Wolf Point twice, he states bluntly, ‘The way Wolf Point is maintained gives the lie to any excuses you might ever hear from other courses as to why they aren’t firm. If Don can have that place playing like that, day in, day out, how come you can’t, with your big crew and your big budget, Mr. Super?’

Indeed, the author contends that a course’s ultimate responsibility is to provide fun, engaging golf while reflecting its own unique environment, and therefore, he considers Wolf Point to be among the handful of best presented courses in the United States. The author’s favorite Wolf Point story, of which there’s a scant few as less than 1,000 people have seen the course, centers around a two-day event. On the first day with the course and especially the greens brick hard and running as fast as 11, players moaned and groaned that there was no way to get close to certain hole locations. Approach shots aimed at the flag were routinely shunted aside, leaving players short-sided with faint prospects for an up and down. Rounds of 80 to 82 were commonplace among good players. The very next day, under similar playing conditions, those same players shot 73 to 75. They understood the course that much better and now appreciated where you couldn’t miss it, how to bounce shots in from the high side, and how to use the contours and short grass as their friend. People don’t come to east Texas, where Bermuda grass is king, expecting to need the imagination required to play links golf – but happily, and almost miraculously, such is the case.

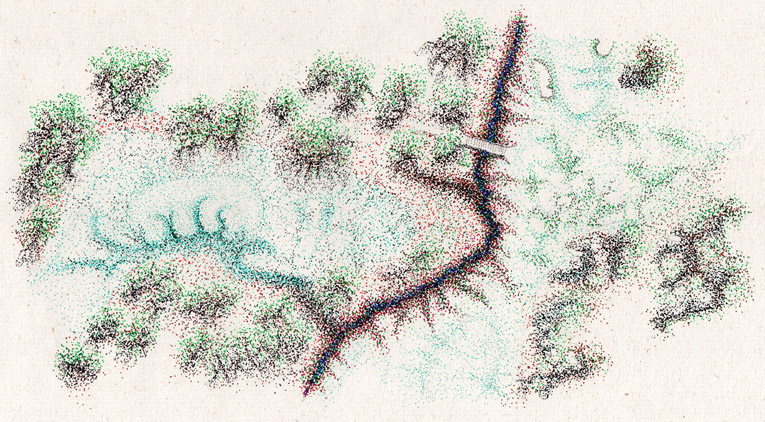

Here is GolfClubAtlas.com’s cover photograph + caption after my first visit here in 2012:

How the ball interacts with the ground is at the soul of good golf. The natural, random land conformations found on links are ideal but skilled artifice is needed for an inland course to enjoy the same playing attributes. In all the world, some of the most graceful man-made contours of the sort that are perfect for golf are found at Wolf Point, a Mike Nuzzo design in Texas. Appreciate the scope of contour in the photograph against the silhouette of Green Keeper Don Mahaffey.

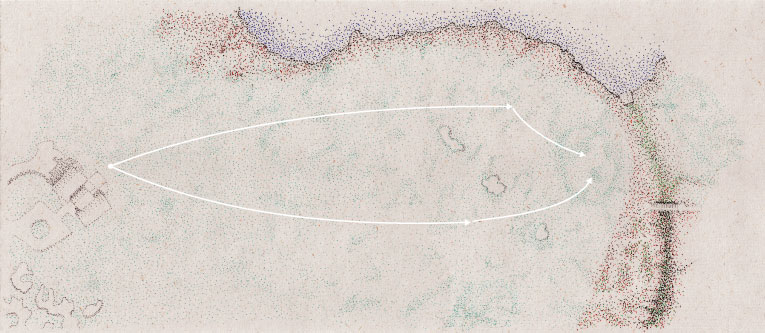

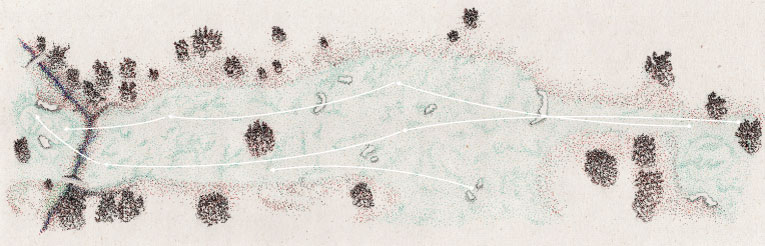

That photograph of Don Mahaffey walking up toward the Home green summarizes the charms of a game here. Nuzzo’s routing with its ever alternating hole directions capitalizes on the firm playing conditions and the ever present wind off the bays and Gulf of Mexico, whose salt water is within smelling distance. Nuzzo takes the golfer on four loops in which the rancher’s home is cleverly used several times as a backdrop. The fourth green returns the golfer to close proximity of the first green, the fifth thru eighth form another clockwise loop, the tenth and fourteenth fairways brush against each other in opposite directions and the fifteenth thru eighteenth constitute a final counter-clockwise loop of sorts. Indeed, the first and second are the only consecutive holes that play in a similar direction. Nuzzo’s inspired cloverleaf routing maximized the very visible Keller Creek as well as the invisible but equally important wind.

While wind renders yardage meaningless (indeed, no yardage is given on the scorecard!), Nuzzo strived to make each hole enjoy a 20 yard or more difference from any another. The par 3s frequently play ~150, 170, 190, and 210 yards, for instance. Fans of the Stanley Thompson chart in George Thomas’s Golf in America will realize that the holes at Wolf Point form the ideal diagonal as seen below.

The top chart represents the yardage per hole; note the appealing variance from one to the next. The bottom chart shows the eighteen holes arranged from shortest to longest, again scoring strong in variety.

A final point about this unusual project, when you head to the first tee, you don’t. There are no tees, not a single set of tee markers exists and the teeing grounds are nearly indistinguishable from their surrounds. Wholly appreciative of this concept, the author also thinks that the aerial view below is most illuminating because the course is largely indistinguishable from its surrounds. This is the highest form of architecture and maintenance in that the course melds with nature and vice versa. Artificial delineations are just that and dilute a player’s connection to nature. In this regard, the course reminds the author of one of his all-time favorite links, Royal North Devon.

This aerial of Wolf Point shows a highly appealing mix of colors found in its molten playing surfaces. Emerald green fairways would look (and play!) heinous against the Texas landscape.

A round here is tantamount to enjoying a walk in the unspoiled Texas countryside. The more frantic your life, the more you will appreciate what a blessing this quiet solitude represents. John Paul-Newport certainly thought so when he visited:

Wolf Point is like the greatest backyard in the history of the world. Front yard, too, since the owner’s house sits in the middle of the course, elevated on landfill from construction. The house is very nice and modern but not the kind of fancy you might expect to accompany a personal course, such as at Sunnylands, the Annenberg estate in Palm Springs, California. Wolf Point was not designed to impress, it was designed to be a relaxing, comfortable place to spend time (not a primary residence) and to be able to walk out the door and play golf whenever you want. The day I visited, the owner (whom I did not meet) was playing with some local guys who drove there in an old Toyota Corolla. As a native Texan, I instantly bonded with the land and vegetation on the course and the creek that winds through the property. The design makes good use of that creek and the few other topographical features. I loved the bump-and-run Scottish aspect of the course, the rugged bunkers and the strategic but not penal character of the holes. My favorite single thing about Wolf Point was being able to choose where to tee off on each hole.

Holes to Note

First hole, 285 yards; Getting play away smoothly was not a prime consideration; the course averages 2 rounds per day! Yet, every first hole has a duty to whet the appetite and entice. This one is ideal in both respects. Acres of short grass extend to the right (well out of the diagram below). No ‘rough’ is in sight from the slightly elevated tee off the hillside of the residence and the green lies straight ahead past three shrewdly placed diagonal bunkers. Depending on the wind, one of the three is seemingly always in play; put another way, you would place your tee ball in one of those three spots if not for the darn bunkers. Strategically, the green opens up from the left as the green cants left, but that necessitates driving nearer the 13-acre lake.

First time players beat the ball long right. After all, why not? Yet, the green’s right to left slope is pronounced enough so that most second time visitors drive the ball left.

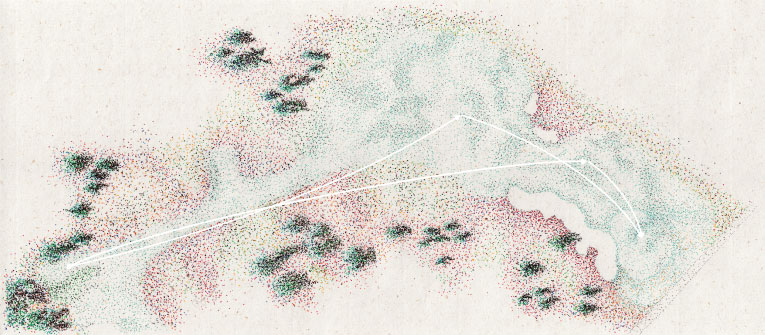

Second hole, 410 yards; In keeping with the owner’s desire to avoid the tedious search for stray shots, wide fairways were a must but avoiding monotony was the trick. Width can easily equate to a thoughtless bomber’s paradise if playing features aren’t placed within the fairway. Just look at the photographs below to see how Nuzzo and Mahaffey created golf of great interest from flat Texas land.

What a pure golf vista, with the rumpled second fairway punctuated with random bunkers. The sight of your tee ball bouncing up 12 or 14 feet in the air off the firm Bermuda fairway completes the picture.

As seen from the right, the second green is largest on the course at a whopping 12,600 square feet but the tiny 100 square foot Lion’s Mouth bunker is so well placed as to receive more play than any other greenside bunker on the course. When the hole is left, the drive must be left and vice versa.

Third hole, 530 yards; This long fairway stretches beside a fence line for one of the paddocks. As such, left constitutes the only hard edge on the course as otherwise the rest of the design is truly free form. Nuzzo uses this edge to perfection, as the only way to reach the green in two is to hug the left where some of the tallest rough on the property resides. Be it the first or second shot, the more the golfer shies away from the challenge, the more complicated his subsequent shot becomes. Nuzzo is quick to acknowledge how Tom Doak and Bill Coore’s work has influenced him and several of the design tenets found on the third at Coore’s Talking Stick North are evident here.

A faultlessly bunkered hole, the third hole tempts the tiger to take the bold line down the left to reach the green in two.

The golfer who plays safely right with his first two shots faces this approach to a green that rolls away from him. It is worth noting that sometimes camels (yes, camels!) are in the paddock behind the green. FYI, the fairway extends thirty yards BEYOND the green, a clear display of the confidence Mahaffey has in his crew presenting bouncy-bounce golf.

Fifth hole, 425 yards; While the impressive Inferno bunker complex, cut into the hillside, dominates the eye from the tee, the real scene stealer lies ahead. Sixty yards and in from this green are found the property’s finest natural contours, vestiges of when the creek was wider. Each evening after construction, the crew gathered near the tree below for some cleansing ales. They talked about the day’s accomplishments and what lay ahead while soaking in these glorious random landforms. Ultimately, the task of imitating those random bumps, humps, and hallows across much of the property fell to Jacob Cope and Joe Hancock, a task at which they excelled.

These grounds served as the template for the intriguing yet low profile contours found throughout the property.

Typical of the rest of the course, the fifth fairway is wide but the challenge stiffens at the green.

Sixth hole, 190 yards; Nuzzo’s approach to architecture is illuminated here where he desires to do something original without borrowing too closely from holes done elsewhere. A natural shelf green-site practically screams “Redan” but Nuzzo opted out because the requisite bunkering would have artificially altered the ground too much. Instead, only a small knob was added at the right front of the green.

Keller Creek makes its presence felt at the one shot 6th, leaving no reason to clutter the hole with bunkers.

Seventh hole, 350 yards; Canadian golf course architect Ian Andrew visited Wolf Point in 2016 and left mightily impressed by how the course rewards bold, attacking golf that is properly applied. Andrew elaborates, ‘Right from the outset Mike lets you think you can hit it anywhere. Brimming with confidence you initially take huge free swings. A couple of holes later you realize you’re not going to have much success unless you learn to play to the appropriate places. There’s just no access to the green from the wrong side. And as the round unfolds the miss played from poor position gets worse and worse costing you more and more shots. What at first felt like complete playing freedom, slowly evolves into a subtle and complicated chess match figuring out how to access those damned greens. While half the greens feature strong slopes, dictating approach angles, the other half are among the most severe greens I have ever played. Where other greens have rolls and broad swales, these greens feature sharp ridges and narrow serpentine valleys. I’ve never seen a tighter set of strong undulations. On others sharp transitions are placed so tight to pin locations that the margin for error is very small … on an approach putt. It’s a course where set-up can take it from fun to frustration with too many tight pins. But there’s lots of great courses that fit the same description. In my mind, where it worked, it was brilliant. There were a few where I wondered if it was crossing the line between being on the edge and simply asking too much. But then again, what’s wrong with that when you put the greens in context with the rest of the course. The fairways are generally really wide, the bunkering is limited, it’s not overly long and there are limitless ground options around the greens. That balances out the demand placed at and on the greens. There are so many opportunities to score, that it balances out some intense pressure occasionally put on your game. It all works.’

Nuzzo’s visit to Royal Melbourne left an indelible impression, as it so often does. One take away was the concept for this hole, which enjoys loose similarities with the eleventh on RM’s East Course.

Andrew was mesmerized by the 7th green and writes, ‘There were greens like the 7th where I felt each contour was a master stroke. The severity and intrigue in the front was balanced wonderfully with the wider spaces and grander flow in the back. It’s a green I wish I built.’

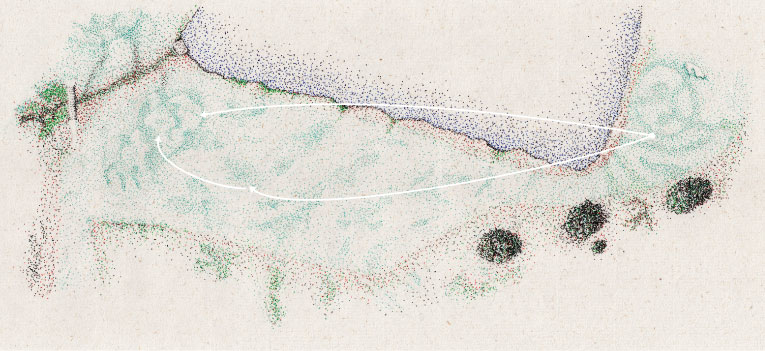

Ninth hole, 585 yards; In contrast to how most architects might have declared this to be the course’s ‘signature hole,’ the ninth worried Nuzzo the most with its crescent fairway bending right around the 13 acre lake. It needed to belong to the course’s overall fabric, not feel like it was borrowed from a water-laden Florida course. Local farmers dug out the lake and built up the nearby hillock where the owner’s residence is perched (along with the first tee, ninth tee, fifth fairway bunkers and the Double Green for the eighth and eighteenth). Just the sight of water causes some consternation on the tee shot but the second is nervier as the fairway runs tight along the lake for the last 180 yards. Complicating matters is how the landing area is compressed by a mound on the left that houses two bunkers. Its origin is interesting. The author had made a faulty assumption that the two to four foot swales, dips, and hollows throughout the course had been inspired by The Old Course. In fact, Nuzzo’s first visit to St. Andrews occurred toward the end of construction with a main takeaway being how large mounds knife into the thirteenth fairway on The Old Course. He loosely borrowed that concept for the complex here to give the second shot added interest.

Like all the holes at Wolf Point, the ninth features a copious amount of playing angles. The sudden, highly visible introduction of the lake causes heart palpitations.

The idea is to get the ball in the hole and the above photograph breams with possibilities how best to do that.

Tenth hole, 270 yards; Even after the rigors of the ninth, the golfer is still accustomed to room off the tee at Wolf Point. Therefore, the sudden requirement to play out over the edge of the lake is intense. Tom Simpson, a fan of the periodic insertion of out of bounds to jangle a golfer’s nerves, would certainly approve of this tactic as the lake serves the same purpose. While the risk for taking the aggressive line is high, so too is the reward. Indeed, the author witnessed Nuzzo drive the green, where his eagle putt grazed the hole.

The bold line over the lake can yield an eagle putt or a golfer muttering as he prepares to tee three.

Considering that this was dead flat grazing ground, overstating the merits of the random humps and bumps and swales is impossible. These ground contours tie the ninth and tenth seamlessly to the other sixteen, non-lake holes.

Thirteenth hole, 475 yards; Look at the diagram of the hole’s last 100 yards: why can’t there be more green complexes like this?! Obvious trouble looms front left but oceans of short grass relent right and long to create numerous options worth considering back in the fairway. A huge flaw in American architecture from the 1950s through 1980s was the deadly, dull monotony where golfers faced putting surfaces pitched toward them. The same challenge presented ad nauseum robs any design of the sacred attribute of variety. At Wolf Point nothing is obvious and the golfer is constantly forced to contemplate how he might best play his subsequent shot. The golfer’s mind is actively engaged throughout the round as he constantly evaluates choices, something that is patently not true at most modern courses.

As seen from behind, this photograph highlights the green’s wonderful front to back slope off the fronting left mound/bunker. What the photograph fails to show is all the short grass that extends well beyond the green. Recovery shots are far less frisky if the approach is long as the green’s tilt becomes the golfer’s friend.

Fourteenth, 560 yards; Ten of the course’s sixty bunkers are found here, including a neat top shot bunker 100 yards from the tee. Additionally, a grove of live oaks occupies the left central part of the fairway some 130 yards from the green. Finally, Keller Creek cuts in front of the green and snakes up its right side. There are three different obstacles to overcome/avoid and how refreshing (but sadly unusual) it is to find all three where they matter most: in the middle of the playing corridor.

How invigorating to find obstacles down the middle as opposed to worthlessly down the sides as seen on other modern courses.

Fifteenth hole, 170 yards; Creating varied playing interest on a relatively flat property is no small feat. Pete Dye built a small mountain at the 5th at Long Cove and again at Old Marsh but the author has never thought that tack fit with the rest of the course. Here, the view from the tee is innocuous: a bunkerless, deep, nearly 10,000 square foot green. Though the hole appears featureless, it is not. World top 100 GOLF Magazine panelist Noel Freeman still screeches with indignation about the ‘crazy’ left bounce his ball took here. The culprit? Hidden off-shoots from Keller Creek that were incorporated into the putting surface, creating three foot hollows and swales that delight in dragging shots away to the left.

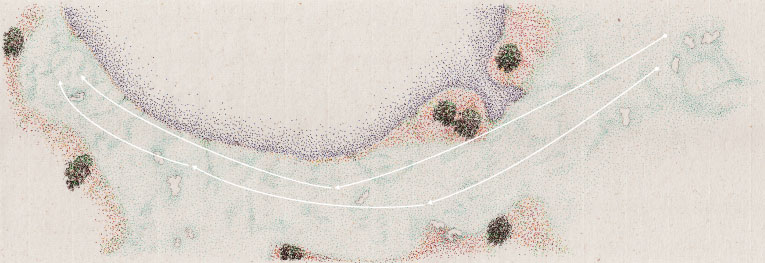

Sixteenth hole, 360 yards; Three two-shotters conclude the round and they couldn’t be more different. This hole leads the golfer into one of the prettiest pockets on the property with live oaks and Keller Creek circling around the back of the green.

The green’s right to left cant means that squeezing one’s tee ball close to the creek makes it easier to control one’s ball once it lands on the green.

The left edge of the sixteenth green is four feet lower than the right. Approach shots played from the right side of the fairway routinely release across the green while those played from the left can use the slope to help brake and hold their approach.

Seventeenth hole, 460 yards; To appreciate how Nuzzo’s worked in simpatico with Mahaffey, and how the design and presentation glorify one another, take a look at the last fifty yards of this hole. Two Spectacle bunkers punctuate a slight ridge some thirty yards before the putting surface and create an unseen ‘dead’ area. Back some 200 yards in the fairway, the golfer is unclear what his eyes are telling him. Without disfiguring the landscape, the architect has cleverly avoided providing perfect optics while creating confusion in the golfer’s mind. Such resulting visual uncertainty à la the sort found countless times across The Old Course helps Wolf Point retain mystery and allure for the owner, round after round, day after day. And for those who only get to play the course once, the sight of seeing your approach disappear over the two bunkers in the foreground before eventually scampering up onto the raised putting surface is not something you are likely to forget anytime soon. In the end, Wolf Point plays exactly how Nuzzo and Mahaffey envisioned her, largely because they were in all the details, from Mahaffey into the deign and shaping to Nuzzo into the maintenance.

Chasing after back hole locations is dicey as the firmness of the turf and the pushed up green pad encourage balls pulled left to find Keller Creek.

Eighteenth hole, 330 yards; The most accurate definition ever of a Home hole, the playing corridor crosses Keller Creek and bends right to finish at a green benched into the hillside upon which … you guessed it … the owner’s home rests. This handsome backdrop lends a sense of occasion to the last but it is the tumbling fairway fifty yards and in to the open green that enchants the old trooper. No more fitting conclusion can be had for both design and presentation than a hooded punch 7 iron that bumps the ball along the ground. Of course, watching it trundle and disappear before emerging onto the plateau green might be dispiriting as you realize you soon be returning to golf back home that is far less exhilarating.

What a great hole location – just a few yards too strong and the ball disappears into the four foot swale.

Built for three million dollars, the design reminds the author of other favorites like Rustic Canyon, Wild Horse and St. Andrews Beach where great design and great economics co-exist. Nothing has been more poisonous to the health of the game than how ‘expensive’ became linked to ‘good golf’ in the 1990s. If only more developers and owners could play here before formulating their plans, the game would be infinitely better-off.

Adam Lawrence has long sounded the merits of Wolf Point and he nailed it when he penned:

When I visited Wolf Point the first time and wrote it up for GCA, I said that I thought it was the best debut course by a modern architect I had seen, but I pointed out that I hadn’t seen Bandon Dunes, an obvious contender. A few years later, Mike asked me to write a testimonial for him for some job he was pitching for; I repeated the ‘best modern debut’ quote, and added that in the meantime, I’d been to Bandon, and given the choice, I’d rather revisit Wolf Point [Jonny Davison’s Heritage course at Penati in Slovakia is a subsequently-seen contender for that title too]. What is remarkable about Wolf Point is that, more than literally any other course I have seen, it uses the lessons of the Old course at St Andrews; that contour is the soul of golf, and that you don’t need massive contour for great holes. It’s so low profile that it must be a pig to photograph well, except perhaps in perfect early morning or late evening light, when you can capture the contours. But also, Wolf Point is a living, breathing case study for how golf should be built in this day and age. No large scale earthmoving, except for the lake, and that was really to build the house (and they even found a creative, low cost solution for that too). The genius of Mahaffey; without him it would not have been built for three million bucks, and it wouldn’t be maintained the way it is, for the price it is. I once asked Mike, if this was a public course, what would you do differently? We both thought about it, and the truth is that only the teeing concept would have to change. If we had a couple of hundred Wolf Point inspired courses around the world (ESPECIALLY IN DEVELOPING MARKETS) golf would be in a much healthier place.

Well said! Moving forward, it is nice to know that fun, engaging courses can be built on not great land for not a whole lot of money. The sooner golf world embraces the lessons espoused at Wolf Point, the better.

The End

![The Park, West Palm (Lit 9) [2023]](https://golfclubatlas.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/IMG_7092-2-scaled-500x383.jpg)