Winged Foot Golf Club (West), NY, USA

Winged Foot West. No course besides Oakmont is so synonymous with the U.S. Open. The name immediately brings to mind images of long par 4s, dense rough, difficult greens and of course, the iconic stone and slate clubhouse built from the rock A.W. Tillinghast dug up while building the East and West courses.

Historically, Winged Foot’s West Course has been the most difficult venue for the U.S. Open. The course has hosted the national championship five times with a sixth coming in 2020, yet only two players have ever broken par over four rounds (Fuzzy Zoeller and Greg Norman at -4 in 1984) and the single round course record in a U.S. Open is 66 against a par of 70. Compare that to Oakmont, traditionally considered the most difficult venue in the country, which has yielded a winning score under par in six out of the last seven U.S. Opens it has hosted and was the first major venue to yield a score of 63 when Johnny Miller’s shot the finest round of the century in 1973.

Why is Winged Foot so difficult under U.S. Open conditions? The West Course does not possess the wind and terrain of Shinnecock, the ocean cliffs and small greens of Pebble Beach, or the ditches, bunkers and green speeds of Oakmont. Even the venerable Bethpage Black, arguably the most difficult tee to green course in the country after Pine Valley, had winning scores of -3 and -4 when it hosted the U.S. Open in 2002 and 2009, while Merion held her ground with a winning score of even par in equally soggy conditions in 2013.

Looking across from the 4th fairway to those of the 5th, 6th and 7th holes, it is remarkable how flat and devoid of natural hazards the front nine of the West Course is despite its legendary difficulty.

The point of the question is not to ultimately conclude that the more difficult a course is, the better it is. Golf architecture has thankfully evolved from that Robert Trent Jones mentality of the 1960s despite the fact that Golf Digest still includes ‘Resistance to Scoring’ as an input for their ranking of courses. Instead it is meant to answer why a course like Winged Foot West has been able to so successfully hold its own against the best players in the world for almost 100 years despite the remarkable advancements in technology and physical fitness during that same time.

The primary answer is of course the greens. Only Augusta National and Crystal Downs are in the same class with a set of 18 unique surfaces that contain all kinds of combinations of humps, ridges, spines and, of course, false fronts. The greens at Winged Foot are not simply divided into different leveled sections requiring the player’s approach to finish in an area of the green to have a chance. They are more like a continuous rolling ocean that requires keeping your ball below the hole as the first priority and then getting it close to the hole as a secondary objective when coming into the green.

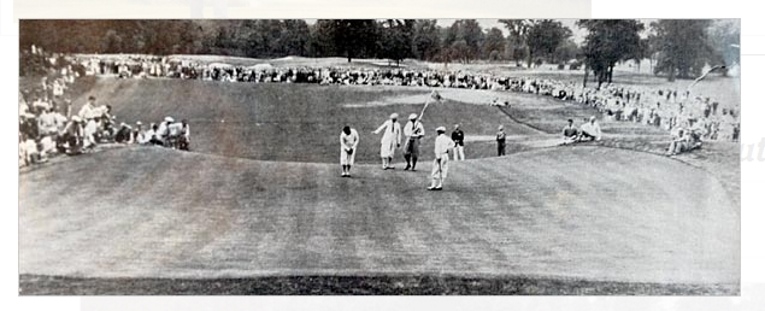

No matter how much longer the ball is allowed to become, the art of holing a pressure putt like the twelve footer Bobby Jones holed to get into a playoff during the 1929 U.S. Open will never diminish (the above photo is from the 36 hole playoff the following day, which Jones won by 23 shots). Note how devoid of trees the course was in its first decade of existence before a non-member donated 2,000 trees from his nursery to be planted in the 1930s. Phil Mickelson certainly would have preferred this setup in 2006.

The second order effect of Winged Foot’s treacherous greens is a great premium being put on driving the ball in the fairway off the tee in order to control distance and spin on the approach shot. This brings us to the secondary (and often overlooked) answer to the question of why Winged Foot is so difficult for the game’s elite players—doglegs. Given how exceptionally narrow the fairways are kept on the West Course, the player is forced to work the ball in both directions to hold the fairway on the many doglegs unless they prefer to lay well back and leave a longer second shot in. Draws are required on 1, 4, 5, 14, 16, and 18 while fades are preferred on 2, 8, 11, 15, and 17. Compare that to Oakmont where straight holes include 1, 2, 3, 5, 7, 9, 10, 11, 15, and 18 but the penalty for missing is much more severe.

Although seemingly devoid of strategy given the lack of hazards, participants in the U.S. Open at Winged Foot are required to make a decision starting with the first tee. A 3 wood will lay back closer to the bend in the fairway allowing for a straighter shot or even a fade, while a driver will have to be turned over by the right handed player to avoid the rough, but will allow for a short iron into one of the most difficult greens in the game. Factor in first-tee jitters and the result is the most difficult hole in relation to par on the entire course during the 2006 U.S. Open.

The treacherous greens combined with the narrow bending fairways and the final ingredient—deep bunkers left and right of every green except the last running flush up against the edges of the greens—present a challenge that requires shot shaping and nerve, not sheer distance. In the 2006 U.S. Open, Phil Mickelson had hit only two fairways during the final round when he reached the eighteenth tee, but it was that final miss that ultimately cost him the championship when the pressure was at its greatest.

Holes to Note

First hole, Genesis, 451 yards; Most descriptions of the first hole of Winged Foot’s West Course focus on two things 1) the hole is flat and 2) the green is diabolical. The second point is undeniable. Before the 2006 U.S. Open, all of the competitors were informed that the greens would be rolling around 12 on the stimpmeter (compared to 14 at Oakmont in 2016) except for the first green, which would be at 11 due to its severity. Clearly the fact that Jack Nicklaus had putted off the first green 32 years earlier in the first round of the 1974 U.S. Open had not been forgotten by the USGA. The first point, however, is a common optical misconception even though the decidedly downhill ninth hole runs back to the clubhouse parallel to the first hole. As a result of misjudging the gradual uphill nature of the first hole, players tend to come up a couple yards short of their expected carry distance into a green that demands precise distance control to the fullest extent.

The first hole was listed at 440 yards in the opening day program in 1923. Almost 100 years later it is only 10 yards longer and still one of the hardest holes in relation to par on the course. Expansion and some careful subtle shaping of the green by Gil Hanse in 2017 should allow this green to run at the same speed as the other seventeen in the 2020 U.S. Open.

Second hole, Elm, 475 yards; Ever since the loss of the Great Elm behind the 10th hole of the East Course, the elm tree standing sentinel behind the second green of the West Course has carried the distinction of being Winged Foot’s greatest living tree. The removal of an additional 300 trees during the 2016-2017 renovation further highlights the remaining specimen trees on the property while still keeping a traditional parkland ambience. A fade down the left side of the fairway provides the optimal angle to every hole location on this green, in particularly the more challenging ones on the right side of the green.

Even in 1923, A.W. Tillinghast found this elm tree so remarkable that he felt compelled to incorporate it into the framing of the second green and named the hole after it.

Today the Elm remains as grand as ever though it is nearing the end of its 150 year expected lifespan. Such is the sad fate that every old parkland courses must face with their specimen trees.

Third hole, Pinnacle, 243 yards; While not as long as Oakmont’s 8th, the third hole on the West Course when the back tee is used to a back right hole location can play up to 260 yards to a much less inviting green. The combination of length and a ridge running from the right center to back left portion of this green is enough to demand a draw or a fade depending if the hole is located in the left or right section of the green. However, the front center hole location is deceptively difficult given it is a narrow target between the bunkers with limited space to be below the hole without rolling down the false front. As a result, approaches tend to end up above the hole when the flag is in the front of the green, leaving a defensive birdie putt which often times can be hit right off the green if the player isn’t careful.

Consider the self-confidence Billy Casper must have possessed when he intentionally laid up on this par-3 in all four rounds of 1959 U.S. Open on route to victory. That is equivalent to a player like Jordan Speith laying up in today’s era. Such is the level of respect that must be given to the greens at Winged Foot when they are firm to avoid ending up with a putt from above the hole.

Fourth hole, Sound View, 461 yards; Two facts about the fourth are rarely known. The first is that that the hole, as stated in the 1923 Opening Day brochure, is “appropriately named Sound View” because the Long Island Sound to the south was visible at the time even from this most northern hole on the property. The second fact is that the green was originally a biarittz style “that is like a piece of paper bent in the middle” but was eventually filled in due to maintenance difficulties sometime in the 1940s. 1929 U.S. Open footage shows Gene Sarazen putting out of this swale (1:03 into the clip). Similar to the large bunker on 17 East, it was decided not to restore this unique feature of the hole unfortunately during the recent restoration. An often overlooked feature is the out of bounds hidden directly behind this green which served as a powerful combination with the original swale and still has some influence on club selection by players today when the pin is in the back of the green.

With both the left and right bunkers having recently been moved 25 yards down range, they become a factor for the elite player again while amateurs now have plenty of fairway to lay back short of them before the downhill approach.

A beautiful opening day picture (hence the hole number sign at the back of the green) illustrating just how severe the swale was originally, particularly on the left. Also note the wicker basket flag stick which was used in the early days of the club’s existence.

After the swale was filled in during the 1940s, it became clear the hole needed defense of another kind so the left and right bunkers were wrapped around the front corners, turning a hole that favored the ground game to one that required an aerial approach.

During the restoration which included the installation of USGA greens, a record was taken of the archeological footprint of the fourth green to document just how wide and deep the swale was originally. Hopefully, after the 2020 U.S. Open, restoring this unique feature similar to the 13th green at Tillinghast’s Somerset Hills will be taken back under consideration.

For now at least the bunkers have been returned to the sides of the green and the approach left wide open for a running shot on this downhill second shot as was the original design intent.

Fifth hole, Long Lane, 516 yards; The same yardage as Augusta’s famed 13th, but lacking the risk reward required of a great short par-5. Unfortunately, the property line runs directly behind the tee, so the hole’s yardage has not changed since opening day and never will unless the home behind it is acquired by the club to add the extra 20-30 yards necessary to be a short par-5 in the 21st century. As a result it will be played as a par-4 for the first time in the 2020 U.S. Open while the 9th hole will return to being a par-5 for the first time since the first U.S. Open at Winged Foot in 1929.

Turning back to the south for the first time, the player will likely face a new wind direction on this tee and is encouraged to draw the ball off the far bunker around the corner to give the amateur a shot at getting to the green in two shots.

Many players in the 2006 U.S. Open said their goal was to be only +1 after the first four holes on the West Course and then try to get back to even over the next three holes. With the fifth playing as a par-4, that first birdie opportunity will now have to wait until the sixth hole. Obviously par is just a system of accounting and does not change who shoots the lowest score to win in the end, but for the greatest players in the world who are used to shooting well under par in every tournament they play, being a couple over par after five holes can serve as a stern test of a player’s mental fortitude and patience which is the hallmark of the exam that is the U.S. Open.

Sixth hole, El, 321 yards; A short par 4 that should be studied and discussed as much as Riviera’s famed tenth. The template is so simple with a lone bunker on the left side of the fairway which opens up the back section of this “L” shaped green for which the hole is named. A creek that winds its way around the left side of the green provides risk to those going for the green from the tee and a challenge to those who have a poor angle from the right side of the fairway and consider bailing out left to avoid the front bunker.

A picture from Opening Day which now hangs in the Grille Room. Note the width of the fairway approaching the green, the low profile of the bunker and how much of the green is visible from this ground view in the fairway.

Over the years the fairway became tightened, a bunker on the left was added unnecessarily to add difficulty to a hole that was meant to be a half-par hole, and years of play from the right bunker had built the lip up several feet and obscured a majority of the green from view during the approach.

Change this hole to black and white and stage a few players wearing plus-fours and it would be difficult to tell this isn’t a picture from Opening Day. Advancement in technology and fitness will have players attacking this hole very differently from the days when Ben Hogan laid back with a 5 iron so that he had a full wedge in to control the distance and spin of his approach. However, it provides a great change of pace from the strenuous test of the first five holes.

Seventh hole, Babe-in-the-Woods, 167 yards; Although it is the shortest hole on the course, the elevated green at the seventh prohibits the player from being able to see its surface and judge the hole location by eye (veteran players will note its location while walking down the 6th fairway through the trees). The hole is further complicated by the “woods” surrounding the hole which make it difficult to judge the wind that is hidden above the tree line and will surely impact a short iron approach. However, if the green is hit in regulation there is a great chance for birdie, for this is arguably the flattest green on the course despite its short length.

A classic pushup green that Tillinghast created out of an otherwise pedestrian landscape, which again begs the question—why aren’t there more courses like Winged Foot? Coming after the short par-4 sixth, players in the U.S. Open will have an opportunity to make a move during this stretch, but a loss in concentration can swing it quickly the other way as Johnny Miller learned in 1974 when he took four shots to escape from the right bunker as the defending champion.

Eighth hole, Arena, 493 yards; To be honest, this is rarely anyone’s favorite hole, but that is due to its poor maintenance over the years rather than its design. Trees planted on the inside corner of the dogleg have grown to the point where there is little chance of hitting the fairway with a driver from the white tees without driving straight over them, making the hole play unlike any other at Winged Foot. Perhaps there actually is still some carryover of the “hard is better” mentality today and is why the #1 handicap hole is kept this way?

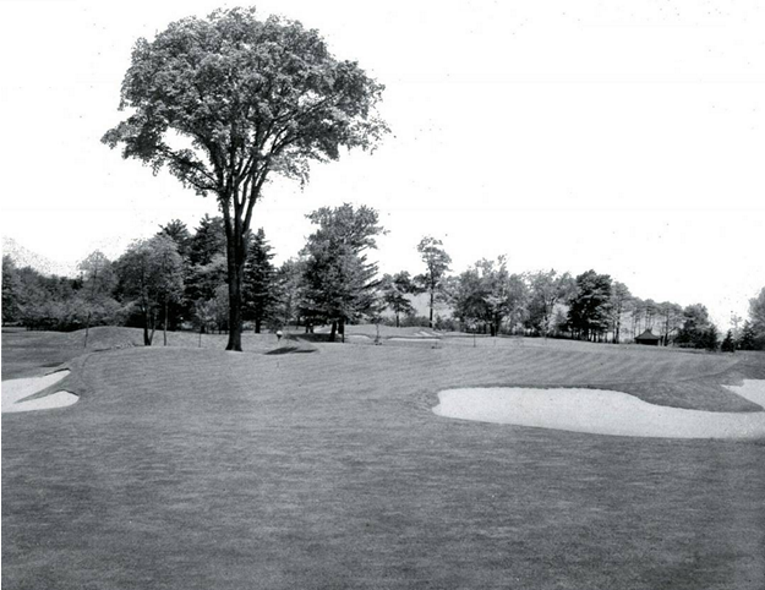

This view from the back of the seventh green provides the best vantage of this dogleg right. The green in the middle of the picture is the 16th on the East Course, while the green for the 8th on the West Course is on line with the two controversial trees to the left of the cart path. Removing these trees would not only reveal a beautiful pair of elms hidden further behind them, but also normalize the drive and frame the hole better off the tee where first time guests are often unsure of where the hole is going.

The Opening Day program states “The fairways are generous. They average more than 55 yards in width. In some places they reach 65 yards.” That is evident in this wonderful oblique aerial from 1925 which illustrates the width of the 8th hole (top middle) coming out of the woods and extending almost into the second fairway to the right.

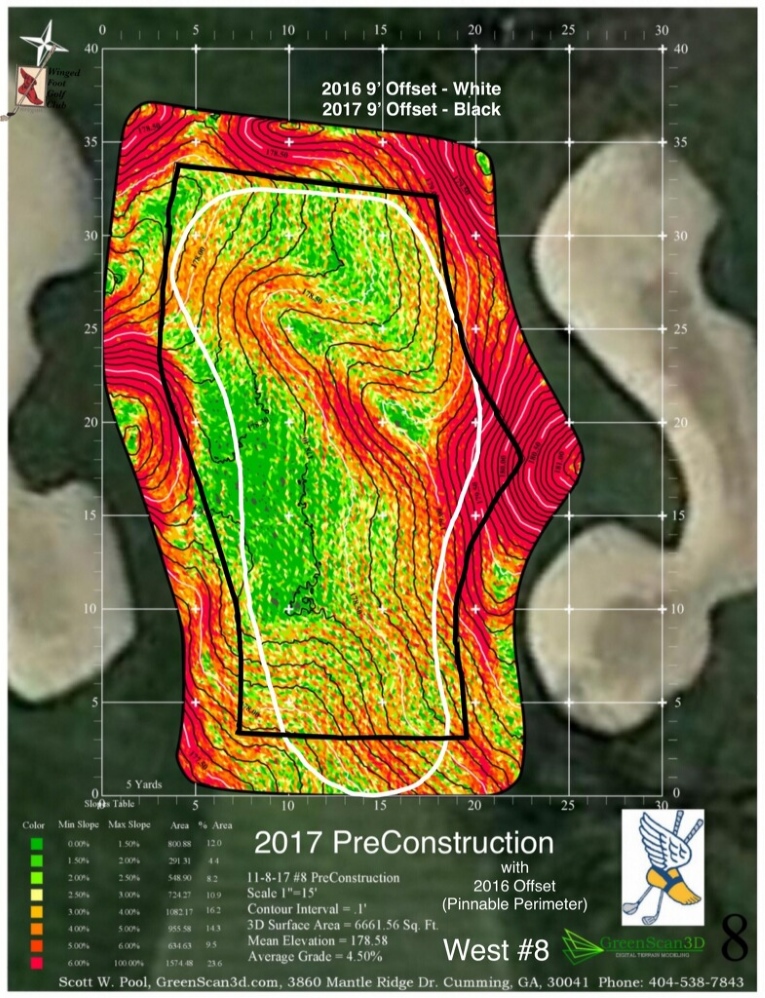

A final scan of the eighth green after it was converted to a USGA green to ensure the contours were returned to within 1/100th of a foot during the restoration. Under U.S. Open conditions the green areas represent useable hole locations. The white line marked the border 9 feet inside the edge of green (i.e. the area for hole locations) and the black line is the new 9 foot border. You can be certain that the newly captured green area in the top left corner will be used in the 2020 U.S. Open. The contour lines here also help demonstrate the rolling ocean nature of Winged Foot’s greens mentioned earlier.

This is how the new back left hole location will look as players prepare to hit their approach shots. Keeping the drive down the right side as much as possible without clipping the trees will be critical in order to have a chance of getting the second shot close.

Ninth hole, Meadow, 572 yards; Besides the short sixth, the player has been asked to shape tee shots left and right on every drive to hold the fairway. The straight sightline of the ninth fairway from an elevated tee can therefore look like a bowling alley if the wind is up. A drive landing in the fairway will run and give most players a good chance of going for one of the largest greens on the course in two.

This view from the new back tee (formally the back tee for 17 East) will measure 575 yards and restore the ninth as a par-5 in the 2020 U.S. Open. With bunkers added down the right in the landing zone, each player who hits this fairway will pickup at least a half shot on the field both from the additional roll and the ability to control their ball coming into the green during the second shot. If the Osage Orange tree on the right is kept, this hole may become a fade hole as well due to the offset angle of the new back tee.

Winged Foot Golf Club (West Course) pg ii

Tenth hole, Pulpit, 194 yards; Like the famous 10th at Riviera or 5th at Pine Valley, Winged Foot West is blessed with having its “signature hole” next to the clubhouse where it can be admired without having to set foot on the course. While Tillinghast is often quoted as claiming 10 West to be the “finest par-3” he ever built, there is no specific reference of such beyond early board meeting minutes where it was reported that the architect admired the hole for its exceptional quality. However, there is no denying it is one of the greatest par-3s in the world, primarily due to its remarkable green. Much like the 3rd, the hole location dictates the challenge of the day, be it front middle with only 30 feet of width between the bunkers, behind the left bunker calling for a high draw, or the rarely seen back center with out of bounds awaiting those who get too aggressive trying to carry the center ridge line. While the right bunker is notably deeper than the left, it is almost always the preferred miss given the majority of the green tilts from left to right, allowing for a better chance of holding the green on the recovery shot.

Ben Hogan famously described the tenth as a “3-iron into somebody’s bedroom”. Technology has reduced that 3-iron to a 7-iron for today’s professionals, although there is a possibility that a temporary back tee will be built for the 2020 US Open to put a long iron back in the professional’s hands. Being the only hole to play Southwest on the entire property, the angle of the wind is typically a new challenge for players as they make the turn.

Eleventh hole, Billows, 384 yards; After experiencing the pedestrian landscape of the front nine, the rolling fairway of the eleventh—where something “volcanic has happened to the terrain” as the Opening Day program describes it—begins to incorporate the added difficulty of uneven lies to Winged Foot’s examination on the back nine. The removal of trees left and right along with significant fairway expansion around both fairway bunkers has brought options back to this short par-4. With the advancement of technology it will be interesting to see if the longer hitters will choose to hit driver up to within 50 yards of the green even if it risks ending up in the rough or second fairway bunker, or if they just lay back short with an iron off the tee for position and leave a wedge in.

The ideal position is at the bottom of the slope in the fairway short of the left bunker which leaves a flat lie and 125 yards to the center of the green. Getting to that position, however, requires a ball landing on the right half of the fairway to avoid getting kicked into the left rough. The fairway beyond the left bunker where the player is standing is somewhat crowned making it exceedingly difficult to hold off the tee with a driver.

Twelfth hole, Cape, 633 yards; A true three shot par-5 to complement the more getable par-5 ninth for the professionals. The second three shotter is a long dogleg left around a line of trees protecting the inside corner and thus requires the tee shot to be played down the right side challenging the fairway bunker in order to have a clear look at the green.

This hump in the fairway had served as a back stop against the longest hitters getting too much roll out on this par-5 for many years. However, in the 1997 PGA a young long hitting Tiger Woods was able to carry it on the fly and send his ball careening forward to the corner of the dog-leg. With only a 7-iron needed in for his second, the hole was stretched from 540 to 630 yards for the 2006 U.S. Open to make this architectural feature relevant again.

One of the early stages of creating a USGA green is the installation of a French drainage along the length of the green as seen here at the 12th. At the same time, the front left bunker is being reshaped to fit the new green expansion. It is remarkable to see the 18 inch lip along the back of the green that demonstrates just how far down this process requires the crew to dig. Don’t try this at home!

A view of the finished product from the same angle. Given the USGA’s penchant to move the tees around in the past ten years, expect the tee to be moved up a couple times on this hole in the 2020 U.S. Open when back ledge hole locations like the one above are used. The left bunker now wraps halfway around the back of this green providing a real hazard for those who go long trying to get home in two.

Thirteenth hole, White Mule, 219 yards; Playing in the exact opposite direction of the third hole, this second long par-3 ensures that the player’s long game is tested during the round regardless of the wind direction. With the front third of the green too severe for a hole location, the hole is almost always in the back half of this green making it play even longer than the distance on the card. Recent widening of both the fairway and the green allows for a running shot when conditions are firm and the hole is playing downwind.

Of the par-3s on the West Course, the thirteenth was the most in need of restoration. The hollow of a filled in fairway bunker on the right side remained, the lip of the right bunker had risen several feet over the years making recovery shots from it completely blind, and the rough line had advanced several yards into the left side of the green limiting hole locations.

With the green fully expanded, the USGA will have several challenging hole locations at their disposal now, none more so than the back center shelf which will make hitting the back right shelf on the sixth hole at Augusta National during the Masters seem easy in comparison. With a firm green and exposure to the wind, this tee shot will be the most demanding for U.S. Open contestants and a fantastic place for those who know the course to spectate and appreciate the abilities of the greatest players in the world.

Fourteenth Hole, Shamrock, 452 yards; Unlike any other U.S. Open venue, the last five holes of Winged Foot West are par 4s and none of them would be considered a birdie opportunity. On top of that, 14, 16 and 18 ask for a draw of the tee while 15 and 17 demand a fade. Many mistakenly believe this hole is named Shamrock after the left fairway bunker, but in fact the Opening Day program again reveals the truth that it was actually named after the shape of the green which Gil Hanse restored to its original design.

In the 2006 U.S. Open an unusual north wind had the fourteenth play as the most difficult the first two rounds and shorter players like Corey Pavin and Mike Weir complained about not being able to carry the left bunker and having to hit a 19-yard wide fairway to the right of it instead. Now that bunker has been moved 25 yards further out and a right bunker added as well but the fairway has been expanded so the hole should play fairer in 2020 regardless of wind while still providing a risk reward advantage for those who challenge the left bunker and catch the downslope. Surprisingly, many claim this to be this to be their favorite driving opportunity on the course despite the landing area being blind. A remarkable design solution and again one worth further study.

Several bunkers were added over the years around this green, most notably the one on the front left which changed the shape of this green. The back portion of the green had also been flattened to try and accommodate more hole locations as a result of losing the ones in the front left. Note again the excessive amount of rough between the right bunkers and the green pre-restoration as well.

Removal of the non-original greenside bunkers and restoration of the fairway bunker, which had to be estimated based on old aerials, was half of the restoration of this hole. The other half of was the removal of more than ten trees behind the green, making the green a horizon green against the back woods so that depth perception is now difficult to judge on the approach. Keep in mind that players were expected to judge distance simply by eye back in the 1920s, not off a sprinkler head or with a range finder.

Fifteenth Hole, Pyramids, 426 yards; The author’s favorite hole on the course and one whose properties Tom Doak featured in his book “Anatomy of a Golf Course”. Once again this Western border of the property provides exceptional topography for golf as illustrated below, but its name derives from the huge piles of dirt that were compiled prior to shaping a green site with over five feet of elevation from back to front.

By extending the fairway out and shifting it to the left, Gil Hanse brought more risk reward to the tee shot at the fifteenth. The USGA has tried to exaggerate this further by bringing the right rough in for the 2020 U.S. Open (seen in dark green in these photos). Somewhat reminiscent of the 5th at Merion, a drive that is long and down the left near the hazard will not only be rewarded with a shorter approach from a flat lie, but also provide a better angle to most hole locations.

Looking back down the fairway toward the tee it is easier to understand why Ben Hogan preferred to lay back off the tee to the top of the hill to gain a level lie with no elevation change on the approach instead of driving his ball down closer to the creek leaving an uphill approach from a hook lie. It is doubtful that today’s professionals will show such restraint…perhaps some will be so daring as to attempt carrying the creek altogether?

This pre-restoration picture of the back of the green illustrates how much of the green pad had become consumed by rough over the years. Incredibly the back right hole location was still used as the Sunday hole location in the 2006 U.S Open even before it was expanded 25 feet. Unfortunately it cost Jim Furyk a three putt bogey on route to a runner up finish by one stroke.

Now fully restored, the fifteenth rejoins the first and eighteenth among the world’s truly remarkable green complexes. Creativity is encouraged here not just on recovery shots but also putts where there are as many as four lines of play for those who have enough imagination!

Sixteenth Hole, Hells-Bells, 490 yards; A beautifully framed tee shot particularly after the back tee was extended an additional twenty yards ahead of the 2020 U.S. Open. Like many of Tillinghast’s doglegs at Winged Foot, playing to the outside of the doglegs affords the better angle rather than challenging the inside corner as players instinctively try to do.

Making the final turn back to the clubhouse, this par-5 converted to a par-4 asks a player to open up with a big draw without clipping the trees down the left.

Trees are often the most controversial part of any master plan to restore or renovate a golf course. While 90% of those removed go unnoticed by the membership, ones as prominent as the two guarding the left side of the 16th green become a source of contention. At the very least it should be agreed that the trees have overgrown their original purpose (if Tillinghast indeed intended them to be there at all) and should be trimmed back to allow approaches for a hole that even most amateurs now take a shot at reaching in two.

Seventeenth Hole, Well-Well, 469 yards: A new back tee stretching this hole 30 more yards also makes the drive even more difficult as the hillside obscures much of the landing area making the trees on the horizon line the aiming points. A fade down the left will kick forward and down the left to right banking fairway leaving a flatter lie and better angle from the right side of the fairway into a left to right sloping green which calls for a draw.

Prior to Gil Hanse’s restoration, trees down the right obscured the green from the tee and often made it difficult for first time visitors to discern where the hole was going from the tee (much like the eighth). Tee shots finishing in the bunkers were forced to play out sideways back to the fairway.

Now the fairway extends over to the bunkers and the removed row of trees tempt players to go for the green on the second from the bunkers instead of being forced to pitch out sideways.

The seventeenth green had shrunk a lot like the thirteenth over the years with the left rough line creeping several paces into the green. Given the left to right slope of the green and the narrow fairway approach, it was incredibly difficult to access hole locations on the left side of the green without one-hopping it out of the rough.

Here is an intermediate stage of the USGA green construction process where a rock layer is laid above the drainage and then locked into place with a polymer solution before the USGA sand mix is poured in. This picture provides a great contrasting image to the one prior of the amount of expansion this green received both on the green itself and the fairway opening into it.

Eighteenth Hole, Revelations, 460 yards: Arguably the greatest inland finishing hole in the world and deserving of a name of biblical proportions like “Revelations”. Winged Foot was certainly fortunate to have Bobby Jones win the first U.S. Open here in 1929 so early in the Club’s existence. But time and again the West Course’s finishing hole has been the story line of the U.S. Open from Hale Irwin’s 2-iron from 220 in 1974, to Greg Norman’s 40 foot par putt leading to Fuzzy Zoeller’s “surrender” in 1984, to Phil Mickelson’s heartbreaking collapse after being one shot ahead with one to play in 2006. Historic moments have happened on this finishing hole because of the thought, execution and nerve it demands of the player when the pressure is at its greatest.

Winged Foot’s long time historian Doug LaRue Smith famously said “Golf is Winged Foot and Winged Foot is Golf”. There is no better way to express the feeling that comes over you walking up the eighteenth, whether it be in a friendly match or the final round of the U.S. Open on Father’s Day.

The eighteenth is the only green on the West Course with bunkers on one side and is one you have to see to believe. Expect hole locations along the left (front, middle and back) requiring a drive down the right near the bunker, before the “Bobby Jones” hole location is used middle right on Sunday in 2020.

Winged Foot West is sometimes described by first-time visitors as a slog of indistinguishable long par fours. However, while it is true that as a par 70, nine of the twelve par fours are over 450 yards, the course is also very balanced with par 3s of 167, 194, 219, and 243 yards, a short and a long par 5 of 572 and 633 yards, and a short par four on each side (321 and 384). Furthermore, a 450 yards hole can be played as a 3-wood and a 9 iron for some of the today’s longest players. Compared that to former head professional Claude Harmon’s 1974 tour of the West Course he did before the U.S. Open that year where he described the first hole as “playing about 450 yards, slight dog leg right to left and should be played as a drive and a 2 or 3 iron.”

Erin Hills played over 7800 yards in the 2017 U.S. Open as a par 72 with five par fours playing over 500 yards in an attempt to put driver back in the hands of the competitors. It did, but the wider fairways allowed the players to hit their go to shot shape off almost every tee and still hold the fairway. That strategy will not hold at Winged Foot in 2020 where players will have to find fairways in order to score on the greens by shaping tee shots in both direction or laying back with a shorter club without challenging the doglegs.

While technology has improved distance it has also improved agronomy and that may also be on display in 2020 as well. Thanks to the installation of USGA greens with Sub-Air, it will take a lot of rain to soften the greens at Winged Foot which provides the true challenge for the game’s elite. The 2017 PGA at Quail Hollow was a great example of this where rain softened fairways made the course play long but Sub-Air kept the greens quite firm making approaches from the rough incredibly challenging.

Both courses at Winged Foot outperform the land that they are on as much as any in the world and for that reason they should be on the short list of required courses for architectural study. While the game would benefit for many reasons if the ball were rolled back 80% including pace of play, economic cost and environmental savings, putting more thought into the creation of thoughtful green complexes and less on length and hazards would provide more enjoyment for players of all abilities without sacrificing challenge. Not every player can carry the ball 290 yards, but everyone has the ability to be a good putter and that will always be the greatest equalizer in the game in matches between a David and a Goliath.

![The Park, West Palm (Lit 9) [2023]](https://golfclubatlas.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/IMG_7092-2-scaled-500x383.jpg)