Wilshire Country Club

California, United States of America

After World War I until the Great Depression, the golf scene in Southern California was one of the most vibrant in the game’s history. Sandy soil, a rugged coastline and rolling land studded with canyons and barrancas were available in this sun drenched, golf-conducive climate. Great architects including Alister MacKenzie, George Thomas, Billy Bell, Max Behr, Robert Hunter and Norman Macbeth populated the state. Other legends, like A.W. Tillinghast, Herbert Fowler, and Seth Raynor were drawn to the west coast. Less is known about Norman Macbeth than most others because he was neither a prolific designer or writer and the passage of time has not treated his works well. Several of his designs met their demise during the Great Depression and others had their playing features greatly compromised. There has been little good news – until recently!

Kyle Phillips Golf Course Design’s restoration work at Wilshire Country Club has brought a renewed appreciation for Macbeth and his work. Situated on 104 acres, Wilshire is surrounded by landmarks, including the Hollywood sign high on the hill to the north and Howard Hughes’s former mansion bordering to the south. Beverly Boulevard now bisects the the property as does a barranca that runs perpendicular to that road. Macbeth’s utilization of the barranca on over half the holes defines the golf. Variety abounds and leaves no doubt about Macbeth’s top-notch ability and understanding of the finest design principles.

His background provides clues to his appreciation of golf design. Born near Royal Lytham & St. Annes, Macbeth became an ace player and in his younger days battled the best, including John Ball, Harold Hilton and Ted Ray. After a brief stint in India, he emigrated to the United States in 1907 and resided for a time in Pittsburgh where he became friends with the Fownes family. After moving to Southern California, Macbeth along with several other members of the Los Angeles Country Club created 36 holes at its new Beverly Hills address. His involvement in course design is hardly surprising as accomplished players have regularly put their stamp on courses. From Old Tom Morris to Bobby Jones, Jack Nicklaus and Tiger Woods, skilled players have often been considered expert on all matters golf. Macbeth’s undeniable masterpiece is Wilshire and it is the course where he lavished the most attention.

At the first tee golfers are immediately introduced to the barranca and deep bunkers that create much charm and peril throughout the round.

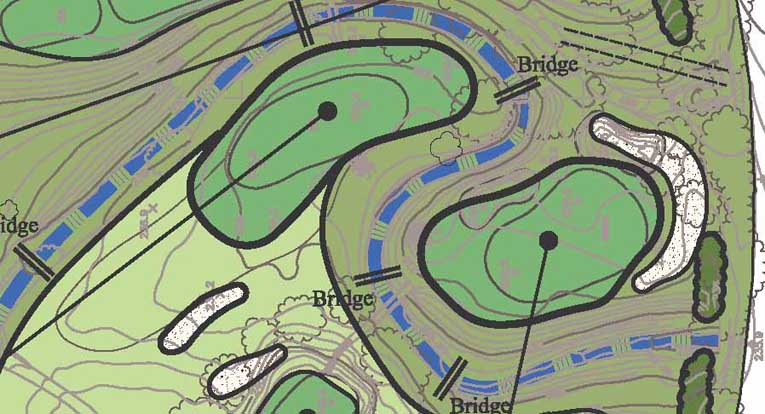

One assumes that the fiercely-bunkered Lytham and Oakmont courses influenced Norman because initially the bunkering at Wilshire was similarly blunt in appearance. Later on, the stylish efforts of MacKenzie and Thomas held more appeal and Macbeth saw to it that Wilshire’s bunkers so evolved. Still, it is MacBeth’s use of the barranca that makes Wilshire a design standout and nowhere is that more evident than at the third and fourth holes. Here, the barranca is especially serpentine and Macbeth capitalized on the design options. Witness the flags in the middle of the third and fourth greens; they are a scant forty yards apart on their respective peninsulas on opposite sides of the barranca. It is really a quite marvelous scene and the resultant shot values demonstrate that Macbeth subscribed to the strategic school of design. Terrain dictates play at the third where the natural grade of the land renders a green falling away toward the barranca (i.e.. left to right and away from the player). The ensuing hole requires a carry over the barranca but this par 3 guarantees a perfect stance and lie for the shot. Two dramatically different challenges are enjoyed in the space of a football field over a span of ten minutes!

The flag for the short par 4 third is in the foreground and the one for the fourth seen behind. Note the graceful lay-of-the-land architecture as the third fairway crests at the spot before bending right.

After a short walk from the third green the golfer is treated to this view of the 9,775 square foot fourth green.

Macbeth wrote in Pacific Gold and Motor in 1920 that Wilshire ‘… has one supreme virtue – that of naturalness; those narrow, winding stream-beds where the clumps of willow grow were put there by the hand of Nature herself, who, if she be not so cunning is at any rate infinitely more artistic than any golf architect.”

Macbeth gave back to the game, serving on various golf associations most of his life as well as the USGA green section in its nascent period. Turf was a special interest and he went so far as to build initially double greens for each of the one shot holes at Wilshire to experiment with what grasses worked best. There is no doubt that he would be delighted with the new strain of Tif-Dwarf 419 Hybrid Bermuda that was planted during the 2008 Phillips restoration. It provides tight playing surfaces which helps the course emulate the links brand of golf that Macbeth admired.

Macbeth’s Wilshire (actually located in nearby Hancock Park) was widely admired and big events, including four Los Angeles Opens, came here. Of course, time moves on. Oil wells once seen in the distance were replaced by homes and the widespread acceptance of the automobile lead to the creation of Beverly Boulevard which now divides the front and back nines. The game progressed from hickory to steel and eventually titanium while trees and shrubs grew – and grew. Wilshire’s defining features – short grass, scale and strategy were badly compromised in the process. Cramped holes that required straight hitting and not much else became a shocking departure from what initially existed. Something needed to be done and most fortuitously the Club hired Phillips who was fresh off his stellar work at the California Golf Club of San Francisco.

Bold action was required and that is what Phillips does best. Wilshire needed the strategies that Macbeth had imbued into each and every hole recaptured. Doing so would enable Wilshire to reestablish its unique identity in the competitive golf landscape of greater Los Angeles. Since there is so little Macbeth architecture, his work at Wilshire stands out and appears startlingly fresh. The player doesn’t feel like he has seen such holes before or played a similar course. Kyle Phillips Golf Course Design needed to polish this tainted gem and restore the luster that folks like Bobby Jones enjoyed here.

The keys of a successful restoration were accentuating Macbeth’s use of the stream, restoring firm playing conditions and recapturing the strategic elements of the bunkers. Huge strides were made so that, yard for yard, Wilshire once again packs a punch and makes demands of the golfer in the appealing manner that defined the Golden Age of golf course architecture. On this course measuring just over 6,500 yards, a golfer must think and play like a chess master and not an automaton.

Golf historian, ardent Macbeth admirer, and long-time southern California resident Tommy Naccarato frames it this way:

Many modern architects have asked me what it is about Wilshire that makes it so enticing to golf architecture fanatics. Well, the first thing I recall thinking on my first visit there – before its most recent renovation – was just how links-like the course seemed despite years of tree growth and urban sprawl. It was unlike that of any other great course in the Los Angeles basin, which no question is due to the credit of Mr. Norman Macbeth, one of the truly magnificent character-personalities in Southern California golf history. When Macbeth came to Los Angeles, he brought with him a wide range of golfing talents and experiences to an area that had very little knowledge of how a golf course should really look and play. With the sport reaching fever proportions in 1919, Wilshire’s founding members backed Macbeth’s every move on an oddly shaped rolling ranch property through which a burn-like creek meandered. With a knowledge of golf course architecture learned on the links of Great Britain, Macbeth found an ingenious routing – one which artfully incorporated the burn-like creek into almost all of the holes in varying directions – which has changed very little to this day. Aside from a tremendous amount of unnecessary tree growth, which is now being rectified, the way in which the creek was altered due to the Los Angeles basin’s Great Flood of 1938 is the only really obvious change to the course from its origins. My great hope is that someday the stars will align and the club will figure out a way to work with the local authorities to restore the burn-like creek to how it originally played around holes 3, 4, 16 and 18. If this were to ever happen, I truly believe that the architecture of Wilshire’s golf course would be on a par with the architecture of the courses at the Los Angeles Country Club, Riviera and Bel Air.

Let’s find out what makes this a one-of-a-kind layout.

Holes to Note

Second hole, 525 yards; A sure way to appreciate an architect’s chops is to see what he does on flat land. MacBeth’s creation of a single mound left of the angled green combined with a trough right is the golfer’s introduction to Macbeth’s engaging form of strategic golf. The mound simulates a dune and Macbeth placed it to angle the line of play. The golfer who can hug the right sees down the length of the green while those that shy left face an increasingly awkward – and sometimes blind – shot into the green.

The tactician weaves his way right past several of Wilshire’s 130 bunkers to gain this view of the putting surface. Howard Hughes’s mansion is in the distance.

This trench along the right of the green is a unique feature. It represents the author’s favorite sort of challenge: Recovery is possible but requires a deft touch.

Third hole, 345 yards; As is nature’s want, the land tilts toward the barranca that runs north to south through the property before reaching Santa Monica Bay. The result is a most pleasant movement within these fairways. There are elevation changes of 8 feet or more at holes 3, 8, 9, 14, 16 and 18. Nothing too hilly mind you, just the kind of undulation that is well suited to the game. How Macbeth deftly incorporated this subtle grade into the design of the third is noteworthy.

The horseshoe stream borders the third green on three sides. These first light golfers will likely finish in three hours and could be at their desks by 10:00 am.

Fourth hole, 170 yards; As mentioned, two separate greens were originally installed at each of the one shotters. Later on, the fourth became one green and during the restoration, Phillips proposed and the Club agreed to restore it to a nearly 10,000 square foot massive green. Its size creates a startlingly diverse array of shots and anything from a wedge to a 4 iron may be required during a full playing season. Before World War II, four greens measured over 9,000 square feet. This was clearly a strategem that Macbeth embraced and he employed it at every type hole imaginable: the drive and pitch third, the par three here, the par five sixteenth and finally at the mighty two shot eighteenth. One thing can be said about Macbeth: the man could build great golf holes.

Fifth hole, 380 yards; The barranca impacts play on thirteen holes (1, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 11, 12, 14, 16, 17, 18). Even more impressive is the varied manner in which Macbeth utilized it. For example, it circles around the sides and back of the third green while it fronts the fourth. It’s similar at sixteen and eighteen where it fronts one but snakes around the sides and back of the other. Drives left and right are menaced at 12 and 17, approach shots at 4 and 16 and both drive and approach shots at 8 and 18. Here at the fifth, the barranca slashes diagonally across the fairway to take a position left of the green where it swallows a pulled approach. Without doubt, the barranca is the property’s most unique feature and Macbeth’s astute routing took maximum advantage of it.

The barranca isn’t the only hazard at Wilshire. Kyle Phillips transformed the bunkers from oval and two dimensional to something altogether more meaningful, as seen above behind the fifth green.

Seventh hole, 140 yards; While the expanded fourth green is the largest putting surface on the course, the seventh represents the smallest making the heterogeneity of these one shotters a highlight of the outward side. Hitting the green from the tee is difficult enough but recoveries, especially from one of the deep greenside bunkers might be more challenging. Only a fool – or a man already desperately down – chases back right hole locations. Pity that this vicious little hole falls on the front nine; late in the round, it would be a pivotal and maddening part of any match.

Ninth hole, 430 yards; Macbeth was not a fan of blind approach shots as Wilshire attests but the occasional blind drive was part of his repertoire and witnessed here. Thank goodness the hillside has never been altered and fortunately it was a Brit who routed the hole and preserved its uncommon character. Cresting the hill provides grand views of the nearby art deco El Royale hotel and the iconic Hollywood sign four miles distant. Squeezing an approach shot past the left bunker and onto the rolling green is one of the day’s most satisfying shots.

Tenth hole, 155 yards; A highly respected one shotter, this hole was built by Macbeth but not until the 1930s. Originally, there was a dogleg right par 4 that bent around the side of today’s clubhouse. During the Depression the club sold off some land prompting Macbeth’s construction of this banana-shaped green. Over 40 yards long, it narrows to a mere seven paces (!) at its waist and in the prevailing left to right breeze presents a daunting challenge.

The green’s unique configuration requires a nine iron to a front left hole location and a mid iron to a back right one. Like the fourth, such diversity is uncommon for a inland one shotter.

Eleventh hole, 365 yards; A variety of reasons exist why a course might measure ~6,300 yards. Most commonly it’s a lack of three shot holes but that’s not the case here. Wilshire length is what it is because of its large number of sub-400 yard two shot holes. There are seven in all and this is the author’s favorite. Thanks to Phillips’s artful bunkering this hole has never appeared better if compared to original photographs. Today’s green speeds exacerbate the problems posed by the putting surface’s severe back to front tilt; fifteen feet below the hole is advantageous to eight feet above. A true position hole.

Second only to the seventh as the smallest target, the eleventh green appears as an island in a sea of sand.

Twelfth hole, 405 yards; Sandy Tatum, whose father was a founding member, has played many rounds at Wilshire over the decades and felt that over that time the largest change was the loss of contact with the barranca. While playing after Phillips’s work, he exclaimed on this tee how nice the barranca’s presence was again. Local ace player Michael Robin notes ahead how short grass confounds around the pushed-up green, representing a nice change of pace from the two prior highly bunkered greens.

Note the width of the twelfth fairway. As recently as 2007, a wall of trees hid the barranca down the left making the hole one dimensional. Note the pushed-up green and the channel of short grass that runs left of it.

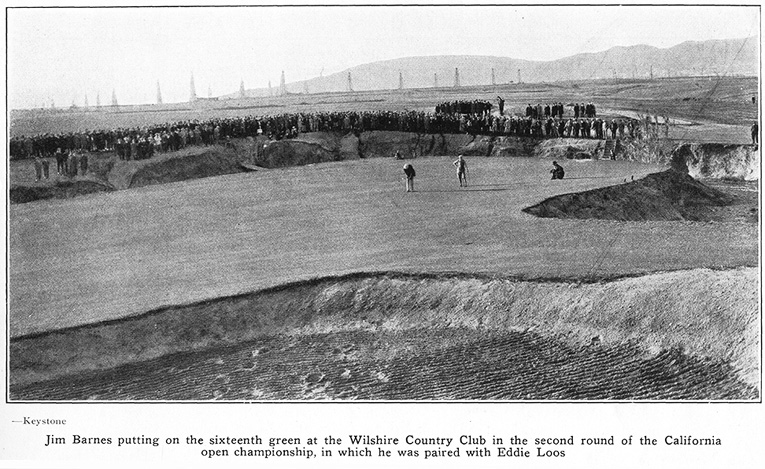

Sixteenth hole, 555 yards; What a hole this must have been in its infancy when hickory golf clubs dominated play. The barranca was wider and even more intimidating and two strong woods plus a solid mashie-niblick were required to cover the distance. Situated on a large peninsula within a bend of the barranca, today’s green still expresses a disdain for sloppy golf but Macbeth’s commanding scale and the naturalness of the green’s position is less apparent.

Note the sheen of the tight, new Tif-Dwarf 419 Hybrid Bermuda turf that was laid down in phase two of the restoration; congratulations to Green Keeper Doug Martin for presenting such superb playing surfaces conducive to good golf. Macbeth would be pleased in the manner in which balls run out, sometimes until they are unceremoniously dumped into bunkers such as these down the left of sixteen.

The sixteenth green is nestled into a soft ‘U’ of the winding barranca. Everything on the far side of the barranca was once putting green making it visually quite striking – and different. Macbeth wasn’t afraid to build trench bunkers around the back of greens, as we see above.

As seen from behind, the sixteenth green is still formidably defended even if the putting surface no longer occupies all of the peninsula.

Using both aerial and ground photos from the 1920s, Kyle Phillips Golf Course Design recreated the Macbeth Course for the Club in 2006. This section highlights Macbeth’s use of the barranca as well as the original massive size (and their proximity to each other) of the sixteenth and eighteenth greens.

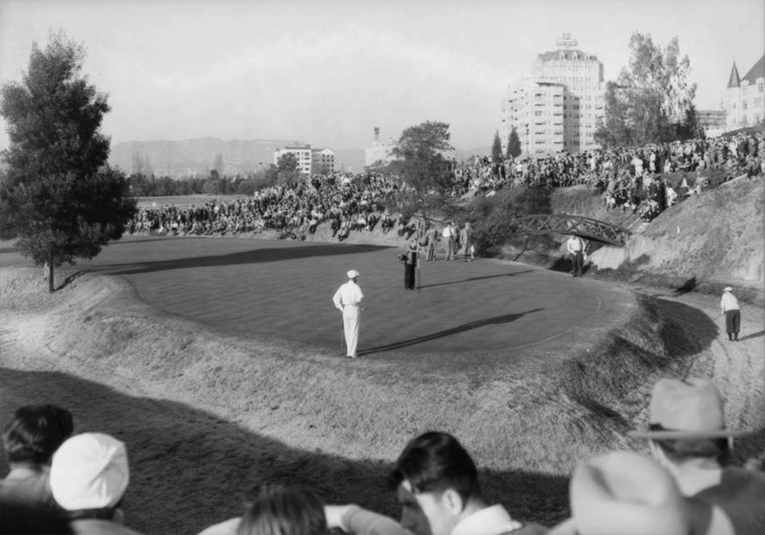

Eighteenth hole, 440 yards; Like Merion, Wilshire demands careful, well judged irons for most of the round and then closes with a beast. Kyle Phillips’s Lead Design Associate Mark Thawley notes with admiration that in its day this gnarly barranca was ‘… surely one of the greatest hazards in American golf.’ Unfortunately, a’ hundred year storm’ deluged the region in 1938 causing wide spread damage to this barranca and the waterways in general. In came the Army Corp of Engineers and while the water network was stabilized, the concrete used by them is a poor substitute for Mother Nature. Much of the aesthetics and some of the strategy was lost. Despite a host of challenges, legal and otherwise the club is considering a restoration of the barranca to its wider, natural state and an enlargement of the green to its original 60 yard length. Let’s hope!

One of the best holes to emerge from the Golden Age is the Home hole at Wilshire. Los Angeles stands proud in the background but the eyes of an old trooper are more likely to be drawn to the mesmerizing color of the turf and fairway contours in the foreground.

The same barranca that threatens off the tee is crossed on one’s approach shot before looping alongside and behind the green. It is the very definition of a well routed hole.

The immense eighteenth green seen in all its glory in 1933 highlights Macbeth as a standout thinker …

Two years after the horrific storm did so much damage to his beloved sixteenth and eighteenth holes, Macbeth passed away. He was another bright ‘point of light’ that migrated from Britain to America who established and nurtured the game of golf. Macbeth shined most brightly here at Wilshire Country Club and it is altogether appropriate that it be preserved and treasured as a monument to what he gave the game.

Naccarato muses:

An aspect about Wilshire that I really enjoy is the history of its membership and the people who visited there frequently. Howard Hughes, the late Billionaire of whose drive and genius I am an ardent fan, was a Wilshire member whose passion for golf was born in Pasadena, where the sport had become fashionable in this region. As his love for golf grew, Hughes’ patience for the game’s difficulty unfortunately did not, which from all accounts was probably the only thing that held him back from being an excellent player. According to his biography, Hughes maintained his Wilshire membership until the day he died, despite becoming a recluse and not having been seen in public for a great many years! I am a hopeless romantic when it comes to golf and Los Angeles, so it’s easy for me to dream about all of the characters Hughes may likely have crossed while at Wilshire….Max Behr, who was also a Wilshire member, MacBeth himself, and, who knows, maybe even a visiting George Thomas! Whenever I look up at Hughes’ former house above the 8th green and 9th tee, I catch myself thinking about a scantily clad Kate Hepburn or Ava Gardner standing out on the balcony, cajoling the Billionaire to hurry up and come home, or of Hughes, much to the chagrin of club officials, landing his plane on the nearby 6th fairway! I then look over at the 9th tee and see a vivid picture of Ben Hogan asking his caddy at which letter of the El Royale Hotel sign he should aim his tee shot! And, yes, that’s the very same hotel at which a certain man at the highest level of the U.S. government purportedly romanced a famous Hollywood blond bombshell! The club recognizes and embraces its history as much as, if not more than, any other club, which gets big points from me. I just love that the club honors its golf designer by annually hosting what is unquestionably one of Los Angeles’ most popular local golf tournaments, the “Macbeth Invitational”, and uses the patented Hughes Tool Co. drill bits as tee markers!

Drill bits make for distinctive tee markers but mind your frustration as they don’t treat driver heads well.

What’s going on at Wilshire is important. More courses built in remote locations won’t drive the game nearly as much as improving courses situated close to one’s home and work. Such courses are often hemmed in by urbanization and lack the capacity to expand and counter technology. That doesn’t bother the author in the least. Golf is meant to be played in 3 hours or less and the amount of ground that a golfer can comfortably walk during that time is in the 6,200 to 6,400 yard range. Wilshire length exceeds that but given the close green to next tee proximity it is one of the quickest walking courses west of the Mississippi. Wilshire represents golf where it matters the most and demonstrates in spades what fun and how engaging a game can be had on a course well under 7,000 yards. Wilshire and its glorious past are the way forward.

GolfClubAtlas.com thanks Tommy Naccarato for the vintage photographs found throughout this course profile.

![The Park, West Palm (Lit 9) [2023]](https://golfclubatlas.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/IMG_7092-2-scaled-500x383.jpg)