The Country Club

Brookline, Massachusetts, United States of America

America’s first country club wasn’t initially founded with golf in mind and it is still the site today for numerous other worldclass pursuits apart from golf. The pond behind the 3rd green was used by Tenley Albright in preparation for her figure skating gold medal performance.

The Country Club enjoys a glorious place at the heart of golf’s development in America. In 1882, it became the first club formed in America for the pursuit of outdoor activities. In 1894, it was one of five charter clubs that formed the Amateur Golf Association of America (later re-named the United States Golf Association). Finally, in 1913, fame was thrust upon it when it hosted the U.S. Open, which was won by the unknown American Francis Ouimet, He bested two British legends and sparked an interest in golf in the United States that has never abated.

Conversely, The Country Club’s influence in the development of American golf course architecture is more subtle, in large part because the design never had a strong central figure like Fownes at Oakmont, Macdonald at National Golf Links of America or Crump at Pine Valley. Indeed, the evolution of the course is a hodgepodge.

The first six holes were laid out in March, 1893 by three keen members Messrs. Hunnewell, Curtis, and Bacon. These holes started near today’s fifteenth and lo0ped counterclockwise around the clubhouse. While none of the holes or features are in play today, golf was underway! The Scot Willie Campbell was soon hired as the professional and he altered and expanded the course to nine holes. Even so, over the next several years, the vast majority of the members of The Country Club remained focused on their equestrian pursuits and only tolerated the golfers who clamored for more land. The slow pace of progress in creating a greater challenge prompted member Herbert Leeds to move on and create a more engaging course elsewhere. The members at the Myopia Hunt Club are forever thankful that he did so in 1896.

By 1899, the course at The Country Club had expanded to 18 holes, thanks in part to the acquisition of an additional 17 acres (the newly acquired land is where holes # 3-6 reside). The Country Club hosted its first U.S.G.A event in 1902, the Women’s Amateur, but the invention of the Haskell ball later that year meant that the eighteen hole course would need to be lengthened and expanded. No professional architect was employed and members, Messrs. Windeler and Jacques, spearheaded the acquisition of an additional 30 acres of land. In 1908, three more holes, 11-13 of the current members’ course emerged from this rock strewn, unwanted jungle that bordered the back of the club’s property. It was on this course that Francis Ouimet forever changed American golf. Finally, the puzzle was completed in 1927 when William Flynn added the Primrose nine, which contributes three and half holes to today’s championship venue.

Despite such a start or because of such a start, the course at The Country Club remains unique among American courses. Common with other Massachusetts courses like Charles River and Eastward Ho! that make the most of their distinctive New England topography, The Country Club doesn’t remind the golfer of any other course. Its greens are among the smallest targets in golf, and are almost one third the total size of the greens at Yeamans Hall, for instance.

The horse stable near the main clubhouse is a tangible reminder of the country pursuits that its members initially enjoyed.

If you have it, flaunt it. The Country’s prudent tree policy in recent years has opened up magical vistas across the course which proudly display the superb rolling New England topography.

The famous Composite or Championship course is the one that people are most familiar with through television and it is profiled below. However, it isn’t the one that the members play on a regular basis – that one is referred to as the Main Course. Later we will look at the three holes from the 6,600 yard Main Course that are excluded from the championship layout. They are quite good and deserve recognition.

Holes to Note from the Composite Course

Third hole, 450 yards, Risk/Reward; Along with those at Royal County Down and National Golf Links of America , this is the author’s favorite third hole in the world. The one of a kind topography sets a grand stage on which there is a latitude of seventy yards to accommodate golfers of varying skills – far right for the tiger who tries to carry the rock ledge and shorten the hole to well left and making the hole a three shotter. No player is forced to play the hole in a specific manner, rather the golfer is left to his own concept. Such an attribute represents the zenith of golf course design and ironically, no one man is given credit for its design. It came into form between 1898 and 1900, which was after Campbell had left the club for Franklin Park.

The tiger may attempt to carry the grassed rock ledge on the right online with the golfer in white in the distance. If successful, he is left with a short iron into the green. If unsuccessful, pain and woe in the form of knee high grass on the far side of the ledge will bring the over-confident golfer back to reality with a thud.

However, the rest of us will have this (scintillating) view for our approach, and be reaching for some kind of hybrid to mid iron.

Fourth hole, 335 yards, Hospital; A hole full of possibilities. With the last seventy yards of the fairway heading downhill to an open putting surface, today’s tiger is tempted to have a go at the green from the tee. However, the green is tiny – a mere 2,130 (!) square feet – and recovery shots, especially from the rough, are difficult to get close. Such holes are fascinating in how they affect the better player who becomes frustrated when his expected birdie fails to materialize. Just like the tenth at the West Course at Royal Melbourne, the hole lends itself to a team match play format, when one man is sure to have a crack at the green.

This view is from the original (lower) fourth tee. Ouimet was terrified of this tee shot which might well have been the most feared in America until the rule change that allowed for unplayable lies. During the 1913 U.S. Open, if a contestant hit it into the bank, he had no choice but to play it as it lies. And play it … and play it! During stroke play, a miss off the fourth tee dashed any hope of placing well.

Ouimet walked up these steps from the lower tee. Hopefully, the club will reinstate the lower tee for occasional use.

In the late 1920s, William Flynn oversaw the addition and construction of today’s elevated fourth tee.

As part of his work since 2007, the club’s architect of record Gil Hanse masterfully massaged/sloped the land short of these bunkers so that tee balls feed into them. Thus, they play bigger than they look.

Big hitters that carry the right fairway bunker might get enough forward pitch from the ground for their tee balls to reach the putting surface.

Conversely, pushed shots, either from the tee or from the fairway, will find a string of bunkers eating into the side of the tiny pushed up green pad. Never overly big, the bunkers at The Country Club don’t always flash toward the middle of the putting surface. Awkward lies/stances are served up more often than bunkers elsewhere. That’s as it should be with hazards being hazardous!

Fifth hole, 495 yards, Newton; One of the quintessential holes at The Country Club, the fifth highlights the key design components that are featured throughout the course. These include the incorporation of distinctive landforms, bending the fairway, and fashioning the green so that its cant reflects its immediate surrounds.

The aim from this new tee constructed in 2011 is over the exposed boulder in the far hillside. Any farther left and the drive ends up in the rough.

This photograph poorly conveys the back right to front left cant of the green that feeds into the slope behind. Putts that break four to six feet are often had here. The photograph does better at illustrating an important maxim for play here: take a caddy! The tilted greens at The Country Club are nuanced and have befuddled good putters for generations.

Seventh hole, 195 yards, The Oldest Hole; Ironically, this is both the best preserved Campbell hole from 1894 and the hardest hole in relation to par at the last U.S. Open (1988). Its fascinating double plateau green is set at a 45 degree left to right angle to the tee, making a high fade preferable. When the hole is on the front plateau, the golfer must land the ball short of the green and it is in this area – the grounds just short of the greens – that Green Keeper Bill Spence and his crew prepare especially well. The turf is uniform and its firm condition enables the golfer to bounce the ball onto this green here, as well as the 1st, 3rd, 4th, 5th, 8th, 9th, 14th, and 15th holes. Given that the holes were designed over 100 years ago when the ground game was king, there would be a complete disconnect between how the holes were intended to be played and how they play without Spence’s excellent work on this oft overlooked area. Too many classical courses in the United States are compromised when water from the fairway sprinklers overlaps the greenside ones to create soft aprons and approaches – not at The Country Club.

The course is not noted for its one shot holes; indeed, it only has three. This is the best, praiseworthy and featuring the oldest double plateau green in the United States. Today’s hole location is on the forward portion.

Note how much more exposed (and inspiring!) the seventh hole is today compared to its more conventional and parkland appearance above in 2002.

Eighth hole, 380 yards, Corner; In the beginning, The Country Club leased 105 acres, which they purchased a few years later. Over the next twenty years, they acquired an additional 70 acres in various bites. A final tract of 55 acres in 1923 made the Primrose nine a reality. In 1904, the eighth green butted against the corner of the property, hence its name.

This strategic sub 400 yarder rewards thoughtful play. The green is open and best accepts shots from the right. Alas, that is where three fairway bunkers are located. Laying behind them into the swollen right side of the fairway is worth consideration.

Ninth hole, 515 yards, Himalayas; Appropriately named, this might well be New England’s finest three shot hole. Alas, it will be function as a two-shotter for the 2013 Amateur! Similar to the third, its fairway twists and turns past a rock ledge, a tempting carry for the tiger who be left with only a mid iron to the elevated green. A world-class course – by definition – must possess world-class golf holes and the third and ninth are two such holes. Another prerequisite is that the course must reflect its surrounds and one play of the ninth leaves the golfer no doubt that he is in New England.

The view from behind the ninth hole shows not only the rock ledge that must be carried but also the creek 360 yards from the elevated tee of which the drive must stay short.

Tenth hole, 480 yards, Stockton; Ouimet noted that the course was ‘subtle.’ Considering its old world charm, one might assume that today’s course has been in play ever since 1899. That’s just not true and in fact over ten architects have worked on the golf course during the past century plus, trying to tweak the course toward perfection. Recently, Hanse added a pair of bunkers at the right edge of this fairway. Previously, the golfer smashed a drive over the crest of the hill and received a big scoot forward. Now, he needs to be wary of the perfectly placed new bunkers. Not only do they defend the portion of the fairway that offers the most level stances, they create the perfect tension with the left greenside bunkers ahead.

Though they may look like they have been there since 1899, these bunkers were built in 2010. Wonderfully realized by Hanse, they make the hole much more strategic. Head Professional Brendan Walsh considers it to be one of the best sleeper holes on the course.

Eleventh hole, 450 yards; No club is more tightly tied to the United States Golf Association than The Country Club. In addition to being one of its five founding members in 1894, The Country Club has produced six U.S.G.A. presidents. In preparation for the 1957 U.S. Amateur, a decision was made to combine the first and second holes of the Primrose course into a long par four with a forced carry over water for the approach shot. Even with the addition of this new hole, the pundits expected record low scoring in the 1963 U.S. Open. Like Merion in 2013, they were proved sadly wrong; nine over par played off for the title in 1963.

The medium long par four first and par three second on William Flynn’s Primrose nine are combined to create an unsympathetic 450 yarder (Flynn’s first green can be seen in the foreground short of the water). As Arnold Palmer can attest, driving in the fairway is paramount. On this hole he registered two 7′s that cost him the 1963 U.S. Open championship.

As seen from behind, finding the bending, rumpled fairway through century old specimen trees is no mean feat. Adding to the challenge is that the fairway is blind from the tee.

Twelfth hole, 625 yards; Wait until the 2013 U.S. Amateur contestants see this hole! It previously played as a two shotter in big events but the club and the U.S.G.A. became disgruntled that the fairway ran out 310 yards from the par four tee. While not an issue at the last big event (the 1999 Ryder Cup), technology and agronomy have conspired to make 300 yard plus drives common at the highest level of play. Having golfers lay back off the tee on a long par seemed wrong so it was decided to create a beast of a par five. Like the previous hole, a premium is placed on getting in the fairway. Otherwise, mounting the forty foot ridge found some 150 yards short of the green becomes highly unlikely. This hole makes its debut on television August 2013 and it might well be the greatest par five hole that only a few people have ever seen.

Bring it on! Like it has since hosting the 1902 U.S. Women’s Open, The Country Club stands ready to defend par and identify the best player. A 300 yard drive leaves a steeply uphill 225 yard carry to reach the fairway at the crest of the hill.

As seen from behind, the golfer hopes to reach the upper plateau in two to set up a straightforward pitch for a cherished birdie. Conversely, the golfer who misses the fairway off the tee is likely left with a blind hybrid third shot from back where pars are gratefully appreciated.

Thirteenth hole, 435 yards; A somewhat unusual sight greets the golfer on the tee: a straight playing corridor where the flag and entire putting surface are visible from the tee! To this point in the round, that’s only been true at the eighth hole. Various design ploys keep the golfer off balance at The Country Club including tee balls over ridges and crests, fairways that move in one direction or the other, elevated green sites and sometimes greens hidden from view. Here, the fairway bends slightly from left to right and shaping a fade into the fairway is highly satisfying. Brookline has always been considered a ‘placement’ course first and foremost and it’s no wonder that tacticians like Julius Boros and Curtis Strange fared so well here.

William Flynn designed this hole and it opened for play in 1929, just when steel shafts were beginning to replace hickory. The Country Club couldn’t have hired an architect with a better design ethos to meld his new work with the club’s existing eighteen holes. Flynn’s touch always appeared light on the land and he favored canted greens as opposed to ones with wild interior contours. No doubt, the Scot Willie Campbell and all those who preceded Flynn would have approved.

Fourteenth hole, 535 yards, Quarry; The Country Club is a cunning course in the sense that the better golfer can always seek an advantage. Only the sixth and fifteenth holes play in a straight line from tee to green, otherwise the holes, like this three-shotter bend one way or another. A long tee ball over a unique grass covered excavation mound shaped like a horseshoe may bring the green into reach but the elevated green has the most back to front pitch on the course. Wedge shots spinning off the green (and even down the hill) in the 1999 Ryder Cup were a common occurrence.

This unique horseshoe mound must be carried off the fourteenth tee. It indicates where a quarry once was.

As seen from the side, approach shots that come up just short will likely roll thirty yards back down the hill.

Fifteenth hole, 490 yards, Liverpool; As played for the 2013 U.S. Amateur, this hole caps off the hardest six hole stretch with which the author is familiar. Beginning at the Himalayas ninth, the golfer plays six brutally long holes, all two-shotters except for the monster three-shot twelfth. What a daunting stretch, regardless of high tech shafts and forgiving 460cc club heads.

Liverpool historically played 435 yards for the last several big men’s events. Hanse added a new tee in 2011, lengthening the hole by some 55 yards. This championship tee fits in well because the 5,250 square foot green is the largest on the course and is open in front.

Seventeenth hole, 370 yards, Elbow; The most famous hole at The Country Club has played as great a role as any hole in the country in determining the outcome of matches. Most great holes challenge the golfer in at least two different ways and that is the case here. Vardon was undone when he drove into the fairway bunker that guards the inside of this dogleg left. His bogey coupled with Ouimet’s birdie gave the eventual champion a comfortable three stroke lead walking up the eighteenth. Countless others including Jacky Cupit have suffered similar fates by getting tangled up on the inside of the dogleg. Cupit’s drive skipped through the bunker, drew a horrible lie in the grass and weeds from where he pitched out, hit on and then three putted! His double bogey wiped away a two stroke advantage and he ultimately lost in a play-off to Boros. At the two-tiered green, great deeds have been accomplished including birdies by Ouimet and Boros on the 71st hole of their championships and Justin Leonard’s miraculous long putt that broke the heart of the Europeans in the 1999 Ryder Cup. The only guarantee at The Country is that the hole location will be on the top tier on the Sunday of a major event. Finding it might well be the most exacting shot on the entire course. Faldo thought he had managed to stay just on top of the 675 square foot plateau in the 1988 U.S. Open only to see his ball roll well back to the lower level. Curtis Strange then hit a wonderfully controlled nine iron to the small target before succumbing to three putts from less than twenty feet. The pressure is amazingly concentrated on this sub 375 yard hole. Pity that there aren’t more holes like this that play a prominent role late in the round at other courses. Holes of this length seem particularly adept at exposing frayed nerves.

No wonder the hole is named Elbow. Do you play a long iron out straight ahead or challenge the dogleg off the tee? That very question has puzzled golfers for over a century. The right to left tilt of the long but narrow green is an important element to factor in as you play the hole.

The inside of the dogleg left seventeenth is well protected by bunkers and rough. The shadow across the narrow putting surface denotes the beginning of a rise to a minuscule back plateau. Over is death.

Other bunkers have been subsequently added to protect the integrity of the inside of the dogleg. Since becoming involved at The Country Club, Hanse has added eleven bunkers to the course. After staking them, he turns the task over to Bill Spence and his talented crew for the actual construction. The green crew’s in-the-dirt work provides a flawless, aesthetic cohesive quality to the bunkers throughout the property, something that didn’t always exist here.

Eighteenth hole, 435 yards, Home; No man can walk up this Home fairway and not be moved by the sense of history and all the great players and events that have preceded him. However, the hole itself is highly memorable thanks to its heavily contoured putting surface which flares up in the back and the massive cross bunker that fronts the green. Architecturally, the hole is also noteworthy for being so splendidly laid out over dead flat land (in fact, the fairway used to be part of the racecourse). The golfer must find the fairway from the tee because an approach from the rough is not likely to carry the cross bunker and hold the firm putting surface. While modern architects pride themselves on giving all levels of players a way to play a hole, this hole makes for a wonderfully uncompromising finish, the kind of old fashioned finish that one expects from a place like this.

Over 120 years ago, the hillside beneath the iconic primrose colored clubhouse was populated by gentlemen and ladies watching horses gallop around a cinder racetrack.

Today, this view up a former polo field shows the dogleg left nature of the Home fairway with its famous fronting greenside bunker in the distance.

Up until the 1960s, the horse racing track was directly in front of the massive bunker that walls off the Home green. The Men’s locker room is in the building behind and there hangs a copy of the charter signed by Chicago GC, Newport, Shinnecock Hills, St. Andrew’s and The Country Club that created the U.S.G.A.

So there you have it – a walk around the Composite Championship Course in sequence with par noted as the course will play for the 2013 U.S. Amateur. The back nine stretches to almost 4,000 yards, which is quite the contrast to the golf first played across these hallowed grounds with a gutty. The need to place long drives in proper positions to open up the canted greens that are surrounded by rough and sand is as exacting a proposition as at any parkland course in the world. No doubt the club’s ability to substitute holes from Flynn’s nine is quite the luxury and has afforded the course the means to withstand the onslaught of technology in a most elegant and seamless manner.

Ouimet’s 1913 U.S. Open preceded Flynn’s work so all of the holes from the Clyde and Squirrel nines were used. It is worth noting that Ouimet won over the following sequence of today’s member holes: 1-8, 11,12, 13, 9, 10, 14-18. No matter the sequence of holes The Country Club has always remained true to its New England heritage.

Before finishing it is worth exploring the holes from the Main Course that are now left out for big men’s events.

Holes to Note from the Main Course

Second hole, 290 yards, Cottage; The members play this as a quaint little two shotter and it serves as the perfect foil between the brutish first and third holes. Big boys in big events see it as a 190 yard one shotter to a green set at an oblique angle to the tee. The author quite likes it as a short two shotter. Certainly, the shallow green is none too receptive and the hole falls across some lovely rolls.

A hybrid off the tee might leave this deceptively tricky approach. Though it looks charming, several factors conspire against the golfer with this back left hole location. Specifically, the green falls toward the left rear into a newly created bunker. Today’s right to left wind helps a poorly considered approach shot find trouble.

Ninth hole, 425 yards, Paddock; This is the first hole played on the members’ course completely eliminated on the Open layout. From an elevated tee, the drive is into the side of a hill from where the golfer is left with a blind approach to a green that falls away. A twenty-foot drop off is only three paces behind the green. Given the firm playing conditions that Spence attains, the golfer who has missed the fairway knows that he must land his approach some 10-20 yards shy of the green. Anything stronger and the ball will scoot across the green and plunge into the deep grassy hollow.

Tenth hole, 325 yards, Maiden; Agronomically, the course is the healthiest it has ever been. A strong argument can be made that the course is also at its peak design-wise as measured against any other point in its nearly 13o year history. One reason is the work that Hanse did to this hole, moving the tee some thirty-five yards closer to the ninth green, improving the hole visually and strategically. According to the Chairman of the Men’s Golf Committee, Chris Kryder, “#10 represents the first major change to any hole since the completion of the Primrose in the 1920s. When we began implementation of the Hanse plan in 2008, this was really a lynch-pin because it accomplished two fundamental goals. We were able to improve the weakest hole on the main course, and simultaneously open up acreage for expansion of short game practice. Given the location of this change, the aesthetic improvement was enormous. Gil has noted that the (former) first tee/tenth tee/practice green complex, cramped and cluttered by non-specimen trees and such visual barriers as chain-link fence and brick drinking fountain, provided a ‘very poor introduction to a world-class golf course.’ We now have a cohesive and stunningly beautiful beginning. And #10 has become a fine, short par four – integral to the pattern of ‘great shorts’ complementing ‘hard longs.’ The term ‘old-fashioned’ has good connotations (e.g. molasses cookies) and bad (e.g. getting spanked by a ruler at school). The Country Club has a decidedly old fashioned feel to it and that is purely in the positive sense. Hence, it is almost a relief to find this very old school hole among the twenty-seven. While some might call it a “drive and a kick”, the hole gains status based on a manufactured mound that blocks the view of the putting surface from the fairway and confounds the approach. According to Wayne Morrison and Tom Paul in their Flynn opus,” The Nature Faker,” Flynn had a role in giving this green its decided left to right cant. A curious design element exists at three of The Country Club’s shortest two shotters, namely the second (played as a two shotter on the Main Course), fourth and here: all three fairways expand to become the widest among the twenty-seven holes. In so doing, the player is given options, which serves to create indecision. For that reason, the author admires the unusual design tactic!

What shall the golfer do from the tee? Play a hybrid safely to the right of the fairway bunker? Perhaps, a three wood to carry the bunker for the sake of finding the widest part of the fairway and leaving only a short pitch? Regardless of the tack off the tee, the object of the second is to hit one’s approach below and right of the day’s hole location.

Twelfth hole, 130 yards, Redan; The author laments most the exclusion of this drop shot par three for big men’s events. There is nothing terribly fancy about it and it is certainly in reach for all golfers but the wee 2,260 square foot green proves an elusive target. This hole has not been used for big men’s events beginning with the 1963 U.S. Open. However, it played a pivotal role in the 1913 U.S. Open, the most historic championship held here. Hard as some may find to believe, this hole extracted ’4s′ from Ray and Vardon in the epic playoff. Only Ouimet had the chops to par it. Further, there might not even have been a play-off if Ouimet hadn’t double bogeyed it in the fourth round!

No doubt about it: the ninth, tenth, and twelfth holes of the members course are not throw-aways but veryfine golf holes in their own right. The Composite Course picks up required muscle when the wedge approach shots to the tenth and twelfth holes are replaced by two long, bruising holes from Flynn’s Primrose nine. Still, for everyday play, the members’ course deserves to be known far and wide based on its own merits. In particular, the give and take within the course (for instance, the half par fourth and sixth holes nicely complement the difficult third and fifth) ensures that the members always look forward to their next go around the course. The downside! The fact the Ouimet won on a different course than Boros who won on a different course from what the amateurs will play in 2013. This creates an uncertainty as to what one means when he expresses deep admiration for The Country Club. Like the members at Royal Melbourne who possess various Composite courses, it’s a good problem to have!

People talk about a new Golden Age of architecture, one that commenced in the 1990s. These modern courses feature wide fairways and wild green contours and lots of short grass surrounding the putting surfaces. They are all well and dandy but if anything, they help one appreciate The Country Club all the more. Challenge players with well-routed holes past interesting landforms, fast and firm playing conditions and small greens and that course will identify the best. Great courses produce great winners and there was no greater win than Ouimet’s in 1913. Interest in golf in America surged after his championship and no one has meant more to the game in America than Francis Ouimet. An entire country rallied around this humble man who forever set the standard for gentlemanly conduct to which we all strive. His exploits as both a great golfer and human being will be forever heralded.

So it has been now for 100 years since his win and The Country Club continues to bring forth the very best that the game has to offer. It is after all The Country Club, no qualifier necessary.

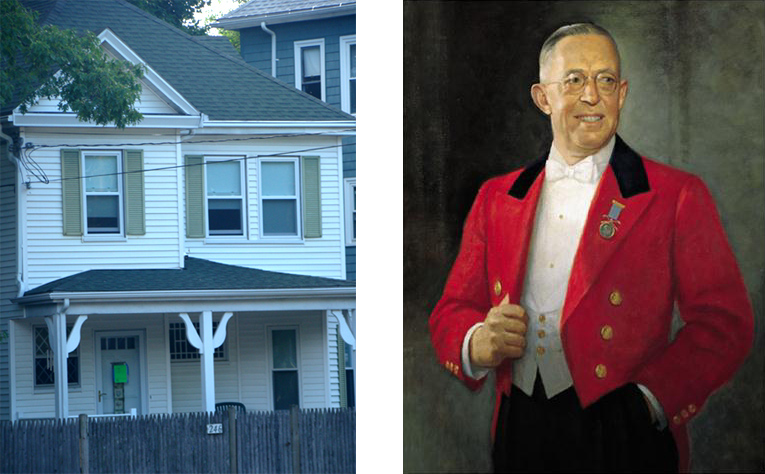

The Brits do things especially well from time to time. One example occurred in 1951 when they selected the man born in this house to be the first non-Brit to Captain the Royal & Ancient Club at St. Andrews.

The End

![The Park, West Palm (Lit 9) [2023]](https://golfclubatlas.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/IMG_7092-2-scaled-500x383.jpg)