Sunningdale Golf Club (The New Course)

Sunningdale, Berkshire, England

The open and exposed Chobham Common provided the perfect place to build a complementary course to Sunningdale’s famous Old Course. As seen above from the back tee on the sixth, long views are afforded across the countryside.

Framing what Henry Shapland Colt meant to golf course architecture is no mean task. Certainly, he was the dominant English architect of the Golden Age of Architecture and his large body of work did more to define golf in the United Kingdom than any other person. Canada, the United States of America, and Europe were also beneficiaries of his personal attention. A great teacher, this modest man’s personality was such that people enjoyed their interaction with him. As a result, the reach of his firm and his design partners extended to all corners of the golfing globe with Charles Hugh Alison in Japan, Europe, the United States, and South Africa and J.S.F. Morrison in the United Kingdom and Europe. Colt’s former partner Alister MacKenzie made his own immense impact in Argentina, Australia, New Zealand, Ireland and the United States as well.

As golf gained in popularity at the turn of the twentieth century, gentlemen desired to play the game closer to their homes/work and that meant building courses inland. Just like Winston Churchill years later, Colt proved to be right man during this crucial transition period when new course construction shifted predominately from links to inland. Though humble, he held strong views on golf course architecture and communicated those to the people around him. In particular, his ability to route courses over interesting landforms and to make inland hazards appear as natural as possible distinguished his work from his predecessors save for Herbert Fowler and Willie Park Junior.

Swinley Forest in 1909 and St. George’s Hill in 1911 are two standout examples and any club that has a Colt course is justly proud. However, of the approximately 200 courses with which his name is associated, one has the greatest connection: Sunningdale. Not only was he the Club Secretary from 1901 until 1913, he also oversaw major changes to Willie Park Junior’s Old Course. In addition, he designed and built the New Course in 1922 and later modified it in the mid 1930s. No doubt from 1901 to 1935, the very dates that some describe as the Golden Age of Architecture, Sunningdale Golf Club and Colt mutually benefited from their close relationship.

When Colt resigned as Secretary in 1913, he did so to board a ship to North America where he was already commissioned to build several courses. In addition to his splendid work in Canada, he spent a solid week at Pine Valley Golf Club at the beginning of June with its founder George Crump. According to historian Tom Paul, Harry Colt helped Crump immeasurably with the routing and left plans for green locations. Specifically, he solved Crump’s routing problem by getting Crump across the river with the creation of the daunting one shot fifth hole. From there, much of the rest of the routing fell into place. Upon concluding his visit to the sand barrens of New Jersey, Harry Colt arrived back in England on June 9th, 1913. A year later, Crump sent a beautiful leather-bound scrapbook of Pine Valley’s construction progress to Colt in England. Though Harry Colt never returned there, he must have been pained by the news of Crump’s death in 1918. Still, Pine Valley Golf Club thought enough of the firm of Colt & Alison that Alison was retained in 1919 to help finish the course.

In England, as the wretchedness of World War I subsided, another era came of age and that was of the motor car. Though Sunningdale was but an hour train ride from city centre, the popularity of the motor car helped spike interest in golfing activities in London’s heathland areas. Hence, the need for a second course emerged at the popular Sunningdale Golf Club and it is no surprise to whom the club turned. 169 acres were purchased from Lord Onslow and Colt’s design opened in 1922. According to Colt historian Paul Turner, ‘This was a big budget project, perhaps the biggest Harry Colt ever worked with in Europe. The New was a grand, sprawling course the day it opened and even featured a hole in excess of 600 yards. Also, it’s interesting to note that the New is one of the few courses that was built when Mackenzie was in partnership with Colt. Though the Good Doctor himself never lays claim to any credit, Joshua Crane makes reference to how MacKenzie assisted Harry Colt at Sunningdale.’

Granted, World War I intervened between Harry Colt’s time at Pine Valley and the creation of the New Course nine years later but the similarities between these two mighty designs are striking. What influence Colt’s week with Crump had on himself – let alone on Crump – is a matter of conjecture but both men deserve credit for their willingness to share ideas and their desire to have the best around them.

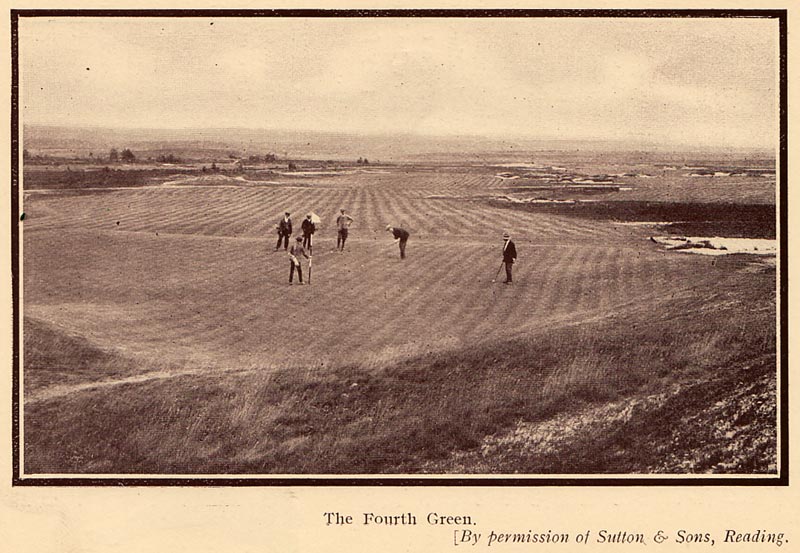

The following three black and white photographs were dug up by Neil Crafter in Australia and are provided here courtesy of Paul Turner. The one above is a view from behind the fourth green of the New Course and shows Colt’s handiwork on the open sandy site.

Never an easy task to open beside one of the standard-bearers of the game, the New Course nonetheless immediately found its own voice. From the start, comparisons with the Old were made but the broad shouldered hitting required on the New proved a fine complement to the cunning charms of the Old. Nonetheless, in the 1930s, the stretch of holes from the sixth to the tenth came under review. According to the club’s well researched centenary book by John Whitfield entitled Sunningdale Golf Club 1900-2000, when Harry Colt designed these holes he was to a large extent tied to the land near the stables, as at that time all the cutting and carting was done by horses; now that work could be done by tractor it was possible to go further afield.

In particular, members complained of mountaineering in this four hole stretch and noted architect Tom Simpson was brought in to provide a solution. Club Secretary Stephen Toon summarizes what then occurred:

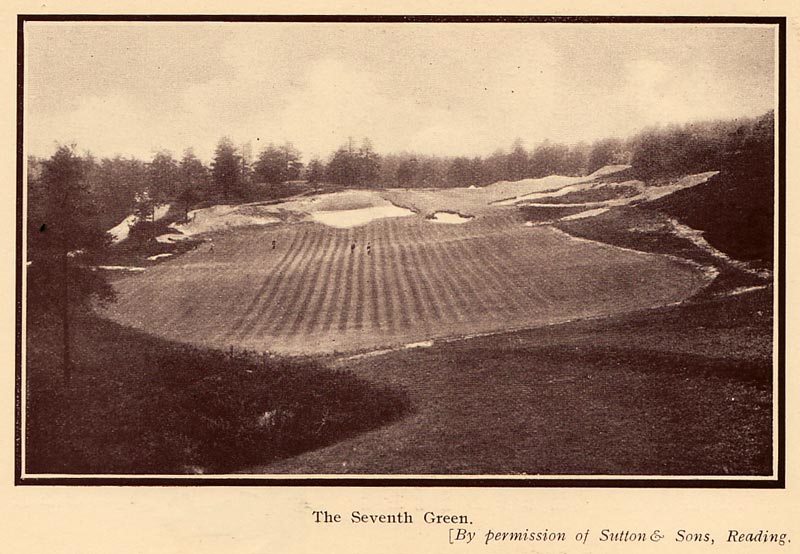

In the early 1930’s, Tom Simpson built four new holes to replace the, eventually, to be abandoned Harry Colt holes. Simpson had been employed on the original construction. These holes ran in a clockwise loop staring at the 6th. HOWEVER after 4 years these too were amended by Harry Colt, in consultation with Morrison. They revised the loop and played them anti-clockwise, as they are played today. Interestingly, the Colt holes remained playable and were very popular with many Members. An entry in the Suggestion Book in 1937 reads: that the holes 7, 8, 9 and 10 of the new course [note the use of the lower case at that time] be brought back into play. The Secretary of the day Major G. G. M. Bennett – replies: The Committee does not approve of this suggestion. This sparks an energetic response from Members who found the Committee’s reply discourteous. It was noted that the suggestion to keep the original Harry Colt holes in play had the largest number of signatures of any suggestion in the history of the Club. The Committee then agrees that the ‘old’ holes may be played ‘occasionally’ which appeased the Membership. So for a number of years, there were two routings in play – the original Harry Colt routing and the revised Harry Colt / Morrison routing.

Colt’s original seventh was found well right of today’s sixth hole in the Longdown section of the property and was on some of the hilliest land. Yet, the appeal in how Colt utilized the natural grade is undeniable!

While the work carried out to this four hole stretch was the most dramatic ever undertaken on either course, the key is that Colt (or one of his partners, in this case J.S.F. Morrison) ended up doing it. Woe is the architect that tinkers with a Colt course, given that his work is likely to be inferior as his feel for the land will be more heavy-handed than the master Colt’s. As holes six through ten play today, they happily co-exist with the other thirteen holes and indeed the sixth is one of the game’s greats.

From a design perspective, the course as it stood in 1937 is largely the course that is played today, though much work was required to bring it back into form after World War II. Nonetheless, courses are living, breathing things that change and in this case, firs and other hardwoods were allowed to take hold and grow, altering the character of the New Course. Instead of being the more expansive course, it played like the Old between corridors of trees. The heather that was so pervasive in Colt’s day receded. Realizing this, the club took steps. In the January 2011 Feature Interview with Club Secretary Stephen Toon and Manager of the Grounds Murray Long, they discuss how the club returned the New to a more open state. With trees down, the wind once again rolls across Chobham Common and is a factor in the day’s proceedings. The turf is firmer and most important from the members’ perspective, they enjoy two very different courses from which to choose.

Holes To Note

Second hole, 170 yards; One reason Colt courses are beguiling to play year after year is that Colt never gave away too much information on the tee. Be it hitting over the brow of a hill (ala the eleventh hole here) or sheltering the view of a green behind a knob (ala the seventeenth), Colt’s courses always keep the golfer guessing. Take this uphill one shotter for instance. With the green some dozen feet above the tee, Colt could have afforded the golfer a view of the entire putting surface – but he elected not to. Indeed, he built a back left plateau that provides some of the most vexing hole locations on the course. Not until the golfer gets near the putting surface does he have any certainty as to the true fate of his tee ball, which helps keep the hole/course fresh round after round.

Very little of the second hole’s putting surface is visible from the tee, thus making it problematic to gauge exactly where the day’s hole location is on the 32 yard deep green.

Third hole, 410 yards; Colt was one of the first architects to appreciate how important the ground in the front of the green was. Read what he wrote in 1920, a year before beginning construction on the New: The entrance to the green, that is to say the portion of the fairway free from hazards on which the approach shot should pitch, should be an object of considerable care in construction. Thirty years ago this point was almost invariably ignored, and even at present time it has not received the attention which it deserves. The consistency of the turf should be such that there is practically no danger of the ball being kicked to one side, or of being unexpectedly pulled up or shot forward. Whether the approach be good, bad, or indifferent, it should receive the treatment which it deserves and should obtain the amount of run which its trajectory and spin indicate. One of the best examples of a putting surface seamlessly tied into the ground around it occurs here and the potato chip waves in the putting surface are things of enduring beauty. Many of the other greens are more overtly defended but never underestimate how much a green like this helps the overall variety and challenge of any course.

Fourth hole, 475 yards; The longest two shot hole on the course is used as a transition hole, transporting the golfer from the treed portion of the property out toward Chobham Common. When members remark that the New requires more powerful driving than the Old, they may well be thinking of this as example #1 as the heather crowds in from both the left and right. Only a drive that finds the fairway offers a chance for the golfer to reach the green benched into the hillside.

What a view down the fourth fairway! Dogs are family members and the fact that they are welcome on golf courses in the United Kingdom is but one reason why it is the best country in the world for golf. Very few clubs of the stature of Sunningdale allow dogs in North America in but another example of how the game is lessened when it leaves the United Kingdom.

This view back down the fourth shows how the hole plays as a switchback: A fade is ideal from the tee while a draw works best on one’s approach.

Fifth hole, 185 yards; As inspiring as any inland par three in the game, the fifth once again mesmerizes golfers, as well as photographers and painters, every bit as much today as when it first opened thanks to the intelligent tree program that the club undertook on the New beginning in 2005. Once again, the green sits as an exposed knob high on the far hill and the golfer will surely feel if there is any wind about. Short is no good, left is worse and note how close the two right bunkers edge into the green. Given that every golfer starts with a perfect lie from the tee, Harry Colt felt that the hazards could be snug to the putting surface on one shot holes.

Even by Colt’s own high standards for building timeless one shotters, surely the fifth at Sunningdale New is at or near the very top. Comparisons between Pine Valley and Sunningdale are never more acute than here.

Sixth hole, 510 yards; When today’s sixth through ninth holes were added into the mix by Colt, Alison & Morrison in the 1930s, an additional thirty acres were acquired bringing the total acreage of the New to nearly 200 acres, which is a very large tract of land and one of the reasons that the New has been described as ‘brawny.’ Also, steel had by now replaced hickory as the preferred shaft and Colt’s firm could factor that in when building this heroic hole (perhaps that’s one reason why this hole stands up better to time than many of Colt’s par fives?). As with the last hole, the sense of expansiveness and of unbound glory that Colt surely felt when he routed it has been fully restored in recent years courtesy of Sunningdale’s tree program. Even as recent as 2004, some of the hole’s grandeur was masked behind hardwood trees along the inside of the dogleg that served no purpose other than to undermine the tremendous scale that this portion of the property enjoys.

Just like its famous sister course, rest assured that the New Course features plenty of great holes too. Pictured above is the mighty sixth from the tee as it sweeps to the right.

Appropriate for a reachable par five, the sixth green complex is a hard one to hit and hold as it falls sharply away at the front, left and right. The modern tiger may well try and reach the green in two but that is far different than carding a ‘4’.

Eighth hole, 400 yards; Given the terrain and natural vegetation, there wasn’t a tremendous call for a lot of man-made hazards (i.e. bunkers). Better than perhaps any architect before or since, Colt knew when to leave well enough alone and not muddle up a picture with extraneous clutter. On the first nine holes, only nineteen bunkers were required – and none on this hole. Couple a fine drive over a sea of heather with a green that is benched from short left to back right into a hillside and the ground presents all the challenge that is needed.

Ninth hole, 460 yards; The best holes always reflect their natural surrounds and the ninth perfectly captures the rambunctious nature of this portion of the property. Initially, Colt was reluctant to lay out this hole in 1921/22 as the far hill crest was a bit too far and the hole a bit too much for hickory golf. When steel shafts took hold in the early 1930s, Colt became comfortable that this hole was manageable for a wide range of playing skills.

Looking back up the hole from behind the green, one gains a perspective as to how much the ninth fairway tumbles downhill.

Tenth hole, 215 yards; Given that this hole provides plenty of fine golf today, the golfer is shocked to learn that the tee was initially ninety degrees to the left and up high on the ridge line all the while playing to this same green. It was a famous hole in its day and Peter Pugh and Henry Lord thought enough to include a black and white photograph of it on the back dust jacket of their book entitled Creating Classics The Golf Courses of Harry Colt (as a side note, a stunning photograph of the fifth is on the cover). The right to left tilt of the green and the manner in which the left greenside bunker chews into the putting surface gives the hole its playing qualities from today’s tee which now has been in use for seventy-five years.

One of the best greenside bunkers on the course is the one that eats into the left and acts as a magnet for any ball that gets near it.

Eleventh hole, 445 yards; Colt was quick to talk about strategy and the use of dogleg holes (as he later perfected at Royal Portrush) was a preferred method for giving the good golfer something to do. Here, a well placed draw can shorten the approach shot by as much as fifty yards versus an opponent who plays out to the right where the ground only serves to kick the ball farther right and away from the green.

Colt liked to place his bunkers on a diagonal to the line of play such as this one found to the right of the eleventh fairway. Is there any more handsome hazard in golf than a Colt bunker draped in heather?!

Twelfth hole, 395 yards; Colt was an expert at using natural landforms for green placement. In addition, he was a big fan of plateau greens and these two come together spectacularly well at the twelfth green complex. Bizarrely, at Tom Simpson’s suggestion, the greens at both the fourth and twelfth holes were briefly played to lower green sites in the early 1930s. Why Simpson would have even suggested such is hard to imagine as both of these greens are among the most attractively situated on the course. As the course plays today, the pacing of the greens and what they ask of the golfer is excellent: The eleventh as seen above is pushed up several feet from its surrounds, the twelfth sits high on a plateau, and the thirteenth is glued to the ground. Such variety helps insure that no one ever tires of playing the New.

As the sun breaks through overhead on the twelfth tee, it is no wonder that some golfers consider heathland golf to be their favorite, even ahead of links.

Not many holes under 400 yards pack the character and punch that the twelfth does. Nothing good comes from missing the green to the left, as the golfer above is about to find out much to his chagrin.

Thirteenth hole, 560 yards; The inevitable comparison between the Old and New yield but few agreements. Two are that the New is the bigger course and also that the New is more exposed to the winds. This hole is a case in point when one learns that it measured over 600 yards (!) in the mid-1920s, making it the only true three shot hole on the property. Simpson brought the green back some fifty yards in 1934 as he thought the flat ground around where the green now resides made the pitch a particularly tough one to judge. Time has shown he was right.

This zoomed in perspective from the tee captures the central hazard one hundred yards from the green that dominates the strategy on one’s second shot.

Fourteenth hole, 190 yards; This picturesque hole with its secluded tee box occupies one of the prettiest spots on the eastern edge of the course. In studying the photograph below, it is interesting to note how much Colt built up and framed to the right of the green. Certainly, the mounds help turn the hole from front right to back left to the golfer on the tee and such framing is more evident later in Colt’s career than in the beginning (the bold features found outside the second green is another example). Thanks to the mounds, anything blocked right is perdition and this is a great tee ball to get right.

The five shotters on the New are a definite strength of the course. As at the second, note the bold mounding that Colt employed.

Fifteenth hole, 430 yards; Where an architect elects to capture a landform within a playing corridor goes a long way in determining how a hole plays. For instance, a tee perched on the highest point has a dramatically different effect than when the green occupies it. In this case, the most dominant landform in the form of a ridge slashes diagonally across the fairway 100 to 120 yards from the green and where one’s tee ball finishes relative to it determines what kind of view of the green one has (perhaps some, perhaps none).

Drainage ditches and a pond on the inside of the dogleg make the fifteenth play longer than its yardage.

Sixteenth hole, 395 yards; Out of bounds comes perilously close to the inside of the dogleg as this fairway bends to the right. Certainly the two tiered green best accepts shots from the right but only the supremely confident and skilled golfer finds himself in the right half of the fairway more times than not during a playing season. On such a big, expansive course, the fact that out of bounds is introduced at such a crucial time in one’s match makes for a real play on nerves. Commenting on diagonal green bunkering schemes such as the one found here, Colt wrote, ‘The longish carry, also, played up to the green over a cross-hazard, should on no account be omitted, as there is a neck-or-nothing thrill about it which is scarcely equaled by any other stroke, and which is enjoyed by golfers of any handicap, although playing it from very different ranges.’

Seventeenth hole, 170 yards; The penultimate hole on the New Course represented ‘build a hole’ time for Colt as he didn’t have any natural features with which to work. Given this freedom, it comes as no surprise that the built-up green complex represents the perfect foil to the preceding one shotter. Whereas the fourteenth begs for a draw, this hole sets up perfectly for a high fade and in marked contrast to the fourteenth, the back and sides of this green feature clean lines with little framing to comfort the golfer.

At twenty-six yards, the seventeenth green is not a particularly deep green and the years have proven it to be an elusive target.

The opening and Home holes lie just east of the eighteenth of the Old Course. That they would start and finish in that broad playing corridor is essentially the only restriction that was placed on Colt when it came time to build the New. Initially the holes played in reverse (i.e. the first tee was near today’s eighteenth green and played back up today’s eighteenth fairway toward near the tee and the eighteenth played down the first hole to a green at the base of today’s first tee). Colt reversed the holes in 1927 and that’s how they have been played since. Indeed, the first might well be the toughest par on the course and the character of the Home hole has been enhanced in recent years by the work done to the bunkers that guard the last fifty yards of the hole.

Having repaired to the famous clubhouse, talk invariably turns to comparing the New with the Old. All the great writers have weighed in on the debate over the past ninety years. Few had the way with words as Patric Dickinson and read what he wrote in A Round of Golf Courses a few years after World War II:

Many people believe Sunningdale Old Course to be the finest inland golf course in England. I am among that number, but qualify the statement by saying, “Wait till the New Course is really in good order again” – as it will be by the time golfers read these words. The two courses are in great contrast. The Old Course winds among trees for most of its way. I do not mean that trees border the fairway, but that the course wears a loose cloak of trees and strides along freely in its heather-mixture within them. The New Course is open; a wild Spartan, utterly different from its neighbour. Only once does it take shelter; otherwise it is open-necked, tough and athletic. I believe it will be a great course. I’m not trying to put supporters of the Old Course into a rage, no; but when both courses are there, if ever an inland championship is to be played – here, I think, is the venue.

Certainly, The Old Course has several holes (namely the third, eleventh, and twelfth) that made major impacts on subsequent golf course architects. Built at the turn of the century, Willie Park Junior’s ability to make the man-made hazards look natural was revolutionary at the time and set a new design standard for inland courses. In fact, it is fair to conclude that the Old Course has had more impact on golf course architecture than the New. In addition, given Jones’s perfect round on the Old in 1926 as well as by virtue of its continuing to host the preponderance of televised events, the Old is also historically more important than the New. However, that is not the same as saying the Old is a better course. Clearly, both the one and three shot holes on the New are better than those on the Old. Yet, no sane man will ever dispute that the twelve two shot holes on the Old are among the game’s best. Hence, the debate has no end in sight and will rage on for years to come!

The sixteenth on the Old is but one of an extraordinary set of two shot holes found on that course. The members are indeed fortunate!

In discussing the two courses, perhaps it is best to leave it as to how well they complement each other. While each has its own distinct personality, they both bring out the best of their natural surrounds. Let’s leave with some words from Colt who wrote, ‘The architect’s earnest hope is, without doubt, that his courses will have the necessary vitality to resist possibly adverse criticism, and will endure as a lasting record of his craft and of his love for his work.’

Surely there is no finer testament to his skill as an architect than Sunningdale.

The End

![Minchinhampton (Old) [2016]](https://golfclubatlas.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/Minchinhampton-500x383.jpg)

![St. Enodoc (Church) [2017]](https://golfclubatlas.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/St.-Enodoc-500x383.jpg)

![Sunningdale (Old) [2014]](https://golfclubatlas.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/Sunningdale-Old-Course-500x383.jpg)