Sleepy Hollow Country Club

New York, United States of America

Green Keeper: Thomas Leahy

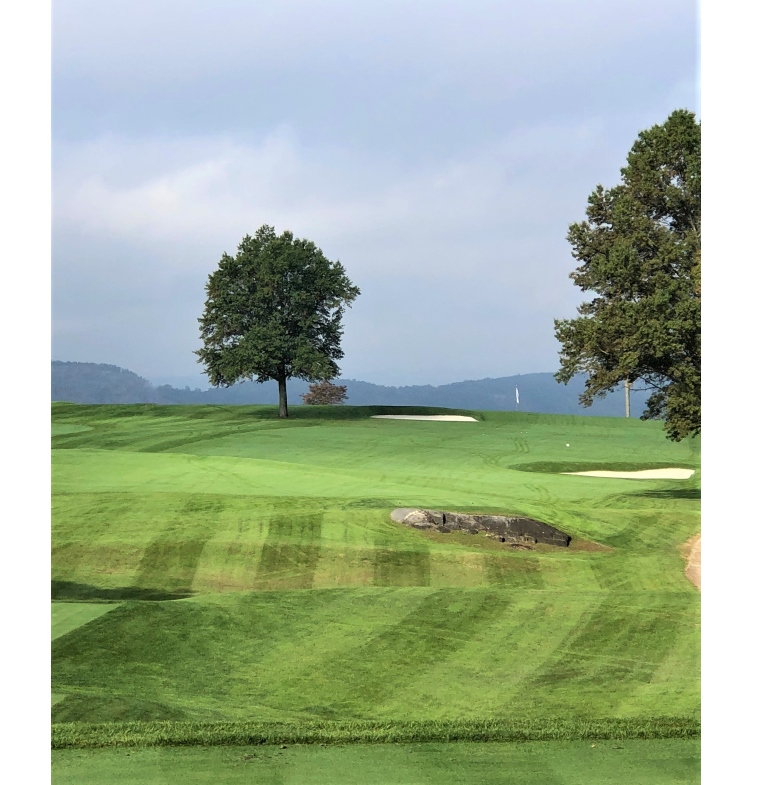

Charles Blair Macdonald’s work dominates the golf landscape as evidenced by the Punchbowl green in the foreground and the Short hole in back.

In 1911 when Sleepy Hollow was formed, golf course design in America was in its infancy. Neither Pine Valley nor Alister Mackenzie’s work existed. Oakmont, Merion and Pinehurst No. 2 had yet to evolve into the design masterpieces that we admire today. The standard bearers included The Country Club, Myopia Hunt, and Ewkanok. Indeed, Charles Blair Macdonald’s own recently opened National Golf Links of America staked its claim as the best in the country and that was soon followed by Piping Rock. Therefore, it was no surprise that a who’s-who group of businessmen headed by Cornelius Vanderbilt, John Jacob Astor and William Rockefeller called on Macdonald to build them the course.

What a setting they had too as it was located on a former Vanderbilt estate. Located an hour northeast of Manhattan, its 340 acres climbed up and over an embankment that afforded one-off views of the Hudson River where it widens to over three miles just north of the Tappan Zee bridge. Hook Mountain and the Palisades provide the leafy, rugged backdrop on the far west side but it is the historic, cobalt blue river that dazzles. Vessels today cruise up and down for commerce just like they have for over four hundred years. It is an integral part of American history and on its east side, Macdonald set about exposing the American golfer to classic United Kingdom features including a Redan (in this case, a reverse one) and a Punchbowl green.

Construction was slow due to the rocky environs and the course opened in 1914. Though it proved successful, hardly a decade has gone by where the golf wasn’t altered in some meaningful manner. In the 1920s, Tom Winton, a local architect, performed work when land that housed four of Macdonald’s holes was sold off. In 1930, A.W. Tillinghast increased the number of holes to twenty-seven when he created the first, eighth through twelfth and eighteenth holes and knitted them into Macdonald’s course.

Both Macdonald and Tillinghast were giants in the Golden Age of golf course architecture. In fact, much of Tillinghast’s reputation for building superb parkland courses is based on his work here in Westchester County. Unfortunately for future Club boards, Sleepy Hollow had a mixture of holes from both titans. Even worse, the best work may well have been done by Winton as neither Macdonald or Tillinghast’s efforts were their finest. Macdonald’s contentious relationship with Rockefeller over tree removal soured him early-on with the project and Raynor was still learning his way under Macdonald, this being but their third project together. George Bahto, the legendary Macdonald expert and historian, summed it up: ‘In all, the course Macdonald and Raynor left the club with was moderate at best.’ Tillinghast helped when he pushed holes into the wooded portion at the high southeastern end but his holes lacked defining qualities. Aerials from the late 1920s and 1930s didn’t offer a hopeful road map. Thus, the conundrum the board faced was how to act as a custodian when it wasn’t certain what it was trying to preserve.

With no clear way forward, a green committee in the early 1990s hired a ‘name’ architect, and trusted his judgment. The end result was a ‘modernized’ course with mounds and small, sculpted bunkers. Within a decade, another architect was engaged to prepare a Master Plan in an effort to restore a sense of consistency to a course cursed with several competing design styles. Close inspection of this architect’s plan by the new green committee chairman, George Sanossian, and his committee developed concerns in several areas including maintainability and suitability. Ironically, some of the architect’s own references were critical of his work. After additional due diligence, the committee pivoted, shelving the Master Plan and posed the question of who could better guide them.

Of the several architects that were interviewed, the decision came down to Gil Hanse partnering with George Bahto or Ron Forse. Both architects recommended that the club proceed with unifying all eighteen holes in the manner of Macdonald as opposed to Tillinghast. After all, Macdonald’s courses found at N.G.L.A., Mid-Ocean, Piping Rock and Saint Louis Country Club are at similarly dated and prestigious clubs to Sleepy Hollow. Plus, it was deemed foolhardy to try to establish Tillinghast as the prevalent design style when a) it never was and b) four of his best original designs (both courses at Winged Foot, Quaker Ridge, and Fenway) are in close proximity to the Club.

Eventually, the green committee proposed the team of Hanse and Bahto, which the Club board approved. Undoubtedly, Bahto’s seminal book on Macdonald entitled The Evangelist of Golf provided comfort to the committee that they were getting the desired Macdonald expertise. The task then fell to Hanse and Bahto to implement the vision for the property that they had shared with the green committee during the interview process. This was by no means a restoration: Macdonald had not even built seven of the holes and those that he did were not feature rich (many lacked fairway bunkers for instance). Rather, this undertaking was to be a renovation of all twenty-seven holes utilizing the design principles and features employed by Macdonald at his best courses. Starting with the third nine, Hanse and Bahto demonstrated the bunkering style and scale that they wanted to re-establish on the main course. The results were enthusiastically received and they were given greater creative latitude when their work commenced on the main course in 2006.

An example of the work that occurred in 2006/2007 is found in how much more open the course became, with longer interior views afforded throughout. Above from left to right is the 14th green, the 13th in the far distance and the 4th green. Compare this 2007 view …

… to this one of the 4th in the fall 2005.

Much to the credit of everyone associated with the project, the work performed at Sleepy Hollow from the summer of 2006 through the fall of 2007 represented one of the great transformations from tee to green in the history of golf course architecture. From a lifeless course that people were indifferent to play, a ‘new old’ one rife with character emerged. Sleepy Hollow became a cherished invite as its one-off joys aren’t replicated elsewhere.

The Club didn’t stop there. By 2012, a small cadre of green committee and board members came to the conclusion that collectively, the eighteen putting surfaces remained a weakness. It wasn’t glaring – the big picture stuff was so compelling – but members including Michael Hegarty, George Sanossian, and Corey Miller started to agitate for going the final step and re-doing all eighteen greens, sympathetic to the Macdonald/Raynor school. When Sanossian approached Hanse about it, he was genuinely surprised and impressed. Back in 2005, Bahto had called for the greens to be done but he and Gil ultimately backed away as it would have been too much for the club to accept. Gridlock would have resulted. Now, after all the accolades and the members having enjoyed the uninterrupted use of their course for five years, the time seemed opportune to finish what they had started. As Hanse states, ‘In the first phase of the project, George Bahto and I pushed for a renovation of the Tillinghast holes (their routing was great but the feature work was uninspiring and repetitive with greens sloping from back to front, bunkers to both sides, and no fairway bunkers on all of the holes) towards holes inspired by Macdonald and Raynor. With the success of the first phase, the club leadership asked us to put together a plan of what a “complete” Macdonald/Raynor course might look like and our plan turned out to be one of the last things that George worked on before his passing.’

Macdonald theme features dominate the view in Jon Cavalier’s aerial. Traces of work by other past architects have been eradicated.

Hanse made several visits and everyone was in agreement to push for Macdonald features wherever possible. Ultimately nine greens (e.g. 4, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14) would be done in the fall of 2016 and the remainder the following year. All told, the greens went from being 135,460 to 145,200 square feet, an increase of over 7%. That isn’t the story. The biggest changes came to six greens (1, 8, 9, 10, 14, and 18), five of which were Tillinghast’s. Those greens account for over 85% of the green expansion but it is what they became that matters.

Take the first as an example. Typical of Tillinghast’s greens, it had evolved into one that was long and narrow with sides that had built up over time. Such a green can have merit but it was repeated too often across the course. Plus, it didn’t ‘fit’ any of the Macdonald templates. With Sanossian’s encouragement, Hanse ultimately settled on a 7,950 square foot Leven green complex. The much broader putting surface is rife with small undulations and puffs and surely possesses a dozen plus really fine hole locations while the old green had but three. Honestly, the new expansive first green is a thing of beauty, nowhere near as fiendish as the all-world first green at Winged Foot West but just as capable of making one pause and appreciate its creation.

So it went. The Tillinghast greens that didn’t engender Macdonald elements were transformed into ones that did. Two of the most dramatic changes were to the eighth which became a full-on Road Hole green complex and the tenth, the worst green on the course, was enlarged by 33% . Though the going was tough due to rocky surrounds, the tenth green now enjoys the scale to belong on a Macdonald course.

It is worth noting that eight of the greens (2, 6, 7, 12, 13, 15, 16, and 17) were already at the edge of their fill pads and weren’t expanded. Green committee member Corey Miller marvels at what Hanse accomplished: ‘Usually when work occurs to greens at classic designs, one of the mandates is to provide more “pinnable” areas. In that pursuit, interest and slopes are sacrificed. Meanwhile, Gil succeeded here in increasing green space and pinnable locations while also making the individual greens more compelling with more – not less – contour embedded into them. We couldn’t be more fortunate.’

When play resumed in the summer of 2018, a journey that started in the last century had come full course. With the greens as good as the rest of the course, Sleepy Hollow now has no known design weaknesses, as we see below.

Holes to Note

First hole, 420 yards, Leven; Macdonald’s course neither started nor finished at the clubhouse, which happens to be a house that Vanderbilt built for one of his daughters (note: his daughter didn’t like it, proving that it’s not always easy to be a Vanderbilt!). Tillinghast added the first and eighteenth holes, though the playing corridor for the two holes is not quite wide enough, given the slope of the land. Today’s first tee complex at the base of the mansion with the sight of the Hudson River in the distance makes any golfer itch to play.

Completely re-built, the 1st green is now a Leven and it is the first of many Macdonald features that the golfer encounters in a round at Sleepy Hollow.

Second hole, 370 yards, Climbing; The most difficult part of the property is the two hundred and fifty yard hill over which today’s second and seventeenth holes are routed. It is an abrupt, broad slope that had to be traversed to reach the best land. Since interest off the tee is modest; the key is to make the approach shot so compelling that the golfer is glad that he hiked up the hill. To do so, Hanse raised the right side of the green in 2006 and then protected it by creating an old fashion eight foot deep bunker around the front and right. The net effect is the short iron approach to the right hole locations is now one of the day’s nervier shots.

Third hole, 170 yards, Eden; Macdonald’s one complaint of the original version of the Eden at St. Andrews was that a golfer could play it with just his putter. He avoided that here as the third plays across a forty foot deep (!) ravine. Macdonald again uses a par three hole (the sixteenth) to traverse the chasm on the inward journey.

The required bridge from the 3rd tee to green is an indication of the site’s rambunctious topography.

One of the more startling transformations from the 2016/2017 work was the emergence of this Eden green. It increased in size by over 10%, expanding both to the left and right. The golfer above has his hands full trying to recover from the aptly named Hill bunker.

Fifth hole, 435 yards, Panorama; As a private club, Sleepy Hollow enjoys limited play. Thus, Hanse/Bahto were free to re-create Macdonald’s interesting diagonal tee shot from a tee in close proximity to the fourth green. After the uphill tee ball, the view from the crest takes one’s breath away as expansive views of the Hudson River and its verdant valley are now afforded thanks to the tree clearing beyond the green. One of Sleepy Hollow’s great attributes is that it resists being categorized. Most consider it to be a parkland course but what parkland course affords such long views?! Macdonald deserves the credit for the greens (e.g. 2, 3, 5, 15, and 16) and tees (e.g. 4, 6, 16, 17) that unveil such moments, as Bahto wrote, of ‘pronounced grandeur.’

This drone shot highlights how Macdonald brilliantly placed five green sites in a compressed area along both sides of a ravine. Going around the clock, there is the 16th, 15th, 5th in the foreground, 3rd and 2nd greens.

Sixth hole, 475 yards, Lookout; One of the more perplexing elements in the Macdonald/Raynor adaptation of classic design features is where they elect to place the Principal’s Nose bunker complex. As is well known, the original is found at the sixteenth on The Old Course at St. Andrews and its position influences the golfer’s thinking on the tee. Does he dare fit a driver between the Principal’s Nose in the left center of the fairway and the out of bounds right? Should he lay back or perhaps go long left? Stuart Paton replicated this dilemma perfectly in 1901 when he added his famous bunkers to the fourth fairway at Woking Golf Club in England. Curiously, Macdonald never did the same. Starting at the eleventh at National Golf Links of America, he frequently placed the Principal’s Nose fifty to eighty yards from the green of long par fours. Raynor in turn copied him at such holes as the first at Yeamans Hall and the sixth at Chicago Golf Club. The author truly doesn’t understand the thinking behind such placement. A far preferable implementation is here on this reachable par five hole where Hanse/Bahto handsomely constructed the Principal’s Nose complex sixty yards from the green. As such, golfers that don’t go for the green in two are left with a real conundrum as to where to place their lay-up.

A wonderful addition, the placement of this Principal Nose is thoroughly original to Hanse and Bahto and creates indecision for those that lay-up.

Seventh hole, 220 yards, Redan; Downhill reverse Redans rarely work well. Downhill means the tee ball is coming in at too steep an angle to properly release and follow the land’s contour. Additionally, a properly played fade doesn’t release as well as the draw that a Redan calls for. However, Macdonald brilliantly saw a unique opportunity to get past both drawbacks, given the pronounced left to right slope of the hill where the seventh cascades.

Given the steepness of the slope that feeds onto the green from the left, the Reverse Redan at Sleepy Hollow functions better than any other the author has seen.

This view from back right highlights how the fairway can be used to kick tee balls onto the putting surface. At 8,600 square feet, it is among the course’s biggest greens.

Eighth hole, 490 yards, Road; After holing out at the seventh, golfers in Macdonald’s day progressed to today’s thirteenth tee as Macdonald didn’t route holes on the section of property where today’s eighth through twelfth holes reside. Tillinghast built these five holes in 1930/31 in part because greenkeeping practices had sufficiently progressed over the prior two decades to address the drainage concerns that held back Macdonald. By 2005, tree growth had narrowed the eighth, making it appreciated only for its sheer difficulty as opposed to more important playing merits. In Stage One, Hanse opened up the playing corridor and captured a marvelous hump within the fairway that sends balls scuttling in every direction. In Stage Two, he cleared even more and introduced the Road Hole green complex. To the author, the work done here best summarizes the huge strides made in Stage Two as 1) the Macdonald thesis was expanded upon with strategic options flowing from the green back to the tee, 2) the approach was made immeasurably more engaging, 3) on the off chance that you should miss (!) the green, the short game interest was wildly improved, and finally 4) the additional clearing continued the process of improving/firming the turf while opening up yet another gorgeous interior view. All of a sudden, the golfer doesn’t mind being removed from the dominant ridge line and ravine.

The right half of the hump in the foreground was under tree branches in 2005, making the 8th a dreadfully dull exercise in straight hitting. With the exposed land form now kicking balls every which way, the hole was re-invigorated despite the limited interest held by the green.

That changed in the fall of 2016 when the 8th green was expanded from 6,100 to 8,400 square feet and …

… became the very definition of a Road Hole green complex. Hanse took considerable time to float in and massage the interior contours so that they would properly feed a drawn approach to this left hole location.

Ninth hole, 425 yards, Knoll; Sleepy Hollow features both violent (as Bahto termed it) land movement as well as more demure moments, such as found in the previous fairway and this one where ~ seven foot, human scale land forms effect play down the center-line. A tee added by Hanse fifty yards back provides intrigue on the approach shot, which is now frequently blind from the base of a hill.

Tillinghast was wise to push into this part of the property as it afforded some fine, graceful fairway movement. The newly created Knoll green is swathed in morning sunlight.

As seen in the fall of 2005, the green complex was dull and lifeless and featured a Tillinghast green that offered a limited number of central hole locations.

Today’s Knoll green features more interesting perimeter hole locations, paired well with the tension created from deep, flat bottom Macdonald-esque greenside bunkers. Green Keeper Leahy came up with the shrewd idea to present the front bank as rough, which makes the Knoll aspect more pronounced.

Eleventh hole, 435 yards, Ichabod’s Elbow; Courses built in the 1910s were rarely replete with interesting playing angles as too often, their playing corridors were straight. That changed in the next decade and of course this hole didn’t originate until 1930. The tee ball at eleven is a fine diagonal one and acts as handsome addition to the course’s overall challenge as it bends around the rocky brow of a hill. Always seeking to enhance (or is that enhanse?!) the strategy wherever possible, Hanse and crew pushed out the back right corner of this green pad in 2017 to create one of the course’s most treacherous hole locations.

Once bland and void of interest, the greenside bunkers at the 11th are among the deepest on the course and make chasing after this newly reclaimed back right hole location particularly problematic.

Twelfth hole, 535 yards, Double Plateau; Over two hundred yards was added to the course as a part of the 2006 work. Amazingly, the overall green to tee walk was reduced. One way Hanse and Bahto accomplished that feat was here, where they created an entirely new green complex, nearly one hundred yards closer to the next tee than Tillinghast’s configuration. In the re-design, the twelfth became a par five sweeping to the left and replacing Tillinghast’s long, straight par four. Presented with the opportunity to build a new green, Hanse and Bahto constructed one of Macdonald’s favorites, a Double Plateau. Another benefit of converting the par four twelfth into a par five which calls for a finesse approach was that it broke up the series of tough two-shotters at holes eight, nine, eleven, and thirteen. Now, the golfer gets to ‘thrust’ versus ‘joust’ with that sense of give and take being a hallmark of Golden Age designs.

Give Green Keeper Tom Leahy and his crew enormous credit for maintaining the area between holes nine and eleven to showcase the property’s rugged charm. Shunned as claustrophobic in 2005, this section is now prized by many for its composition of rich textures.

Thirteenth hole, 410 yards, Sleepy Hollow; Bahto wrote, ‘When we began there were few or no fairway strategies on the course, so we used our best estimations of how these men would rebuild this course today into a thinking man’s Macdonald style golf course.’ Of the eighteen fairway bunkers added during the 2006 redesign, none were impaled upon the landscape. Rather, Bahto spent days walking the course, getting to know the subtle rolls and ground permutations. A case in point is the thirteenth, where he cut a long cross hazard into the ridge line. Much to the Club’s credit, they allowed Bahto total access to the property throughout the scope of this project, allowing him to capitalize on the site’s natural attributes. Great clubs do great things and they made Bahto an honorary member two years before he passed. He told me it was one of his greatest honors and richly deserved as no one did more to shed light on Macdonald’s contributions to architecture than Bahto.

A strategic gem thanks to Bahto’s bunkering scheme, the 13th is one of the star holes in the mid-section of the property. Pre-2006, fun at Sleepy Hollow was confined to the holes along the ravine and the great views. Now, the best golf is evenly spread throughout the round.

Fourteenth hole, 415 yards, Spines; It’s a sad day when a hole that measures over 400 yards is considered ‘short’ but that’s the mess we find ourselves in with technology. Nonetheless, this clever placement hole is made by its green. At one point, it was the smallest on the course, measuring a scant 17 paces across and was the only putting surface under 6,000 square feet. An aerial photograph captured just how much it had shrunk since Macdonald’s day. Before he passed away on March 18th, 2014, Bahto had secured a black and white photo whereby the fourteenth green’s distinctive contours were clearly visible; it was the only photograph from which they could glean long gone contours. Therefore, during the 2016/2017 work, Hanse was especially keen to install the visible pair of ‘rails’ that protruded in from the rear of the green. A multitude of interesting hole locations now exist thanks to these novel spines and dictate strategy back to the tee.

Note the two spines that pierce the 14th green. As the putting surface is hidden from view on the tee, be mindful to take a quick peek at the fourteenth after holing out at the nearby fourth green to determine where the hole is located … and therefore, where the drive should go.

Fifteenth hole, 500 yards, Punchbowl; Only a handful of modern architects would build this hole today; more is the pity as it is a fantastic Alps/Punchbowl, right up there with the fourth at Fishers Island for exhilaration. Sometime after World War II, it was converted to a par five of 520 yards with a tee well back up the hill from the fourteenth green. The majority of members were left with a pitch into the vast punchbowl green, a terrible waste as such a shot mutes the fun of using the land’s downward slope to trundle one’s approach shot onto the green. By moving the tee closer to the fourteenth green, not only was another long green to tee walk reduced but the fifteenth was returned to the par Macdonald intended. Once again, the golfer must finely gauge how to use the land on his lengthy approach shot. Such a laudable design attribute is lacking on most heavy clay-based courses but not here.

The short right and long left bunkers sit perfectly upon the sloping land. At over fifty yards in width, the fairway is appropriately one of the widest on the course. Though the approach is blindly aimed at the flag pole, the thrill of…

…scampering to the crest of the hill to see where the ball lies within the punchbowl is undeniable. Once again utilizing the ground contours short of the green are crucial to playing the hole well.

The round builds and builds with the unquestioned highlight being the sight of the Punchbowl and Short greens juxtaposed against the Hudson River. Few inland courses can compete with such unabashed glory.

Sixteenth hole, 150 yards, Short; This Short has been returned to its original preeminence. Taking a poor picture from this tee is impossible, which is fortunate as scores of pictures are taken from it on a weekly basis! Just fifteen years ago, the green was hemmed in by trees and suffered from artificial mounds and small bunkers that were incongruous with the grandeur of this magical setting – the hole looked fussy. Mercifully, Hanse and Bahto’s work compliments the natural wonder. Coupled with the wind and some of the best interior green contours on the course, this is far more than a glamour hole and the 10,500 square foot putting surface elicits more three putts than any other, thanks in part to the classic horseshoe imprint that was restored in the back middle of the green in 2017.

No hype required. The tee and green are located along two ridges, separated by a ravine. Not that it matters for all eyes go beyond.

Pre-restoration this was a cluttered hole whose man-made features distracted the eye from what really mattered.

The shadows on the green show its contours and help explain why this hole location is quite difficult.

As seen from behind, the restored ‘thumb print’ to the Short green shows the club’s commitment toward uniting all 18 putting surfaces with Macdonald attributes.

Seventeenth hole, 445 yards, Hudson; Giving a hole that falls this sharply downhill good golfing qualities is difficult. Hanse and Bahto worked well with what the terrain offered, focusing their attention on the green site and building a long serpentine bunker that works in perfect concert with the fairway’s left to right cant. The penultimate hole at Gullane No. 1 falls similarly and one wonders if Macdonald paid heed to such during one of his visits to nearby North Berwick? This hole was Macdonald’s Home hole.

Staying left off the 17th tee is of paramount importance on this positional hole. The fairway won’t help as it delights in shunting the ball right.

Eighteenth hole, 425 yards, Woodlea; The Home hole plays nearly forty yards longer than its yardage suggests as both the tee ball and approach are played uphill and get little roll. A monstrous amount of time and effort was spent on the greenside bunkers and site drainage to give golfers more fairway for their second shots in 2006. So good is the work that no one would ever guess that nearly one thousand cubic yards of fill was imported. Just as important, Hanse completely recast the green in 2017, making it bigger and creating a wicked false front by raising the putting surface. It isn’t the best hole on the course but it is emphatically the hardest.

Vanderbilt’s former estate house was known as Woodlea and was designed by Stanford White. It has served as the clubhouse for over eight decades and provides a suitable (!) backdrop to events on the Home hole.

Here is what the author wrote in 2007:

‘Though the above course description may sound perfect, work still remains. The tenth is now out-of-place with its all-water carry to a rock-lined green. Perhaps the tenth at Chicago Golf Club, which also plays over a pond, can serve as a model. C.B. Macdonald first built the hole at Chicago in 1892 and it is one of the few holes that his protege Seth Raynor elected to keep when he re-did the course in 1922. Ben Crenshaw calls it ‘one of the most fun to play’ because its imaginative green contours of two shallow bowls divided by a ridge create so many interesting hole locations. Indeed, such a move by the Club would solve the only other remaining weakness of the course, which is that the interior green contours are presently good without being great. Added character to a few greens such as the tenth in keeping with Macdonald’s style would complete the course’s return to the upper echelon of the small, select family of Macdonald courses.’

Such reservations were completely addressed in 2016 and 2017. The course is now homogeneous to the Macdonald school of design, everything from tee presentation to bunkering schemes to putting surfaces and strategy. True, Tillinghast deserves his fair share of credit for providing seven of today’s playing corridors but there is no doubt that his holes are the most engaging that they have ever been thanks to Hanse’s work. Sleepy Hollow has joined forty or so Golden Age courses around the world that are better today that they have ever been. Its path to get here was anything but simple and required great patience. Golfers, now, are free to appreciate a wonderful variety of holes in a setting devoid of outside interference. Its holes along the ridge line are among the most exhilarating in inland golf and the supporting cast is infinitely stronger than it was just a few years ago.

Of course, one thing the reader might well wonder is how did Sleepy Hollow pull off not one but two highly successful rounds of work to their course over the past dozen years? Most clubs can’t get it right once, let alone twice! A few elements came together. First, Hanse is the master of membership meetings and his calm, polite demeanor instilled confidence in the fall 2005 to the membership that this was a man to whom they could trust their course. Second, starting on the third nine was a low risk maneuver to introduce the members to what was being proposed. Like most memberships, if they like what they see, they can quickly become supportive and embrace the undertaking. From there, the architects enjoy more freedom in the field. That pattern is exactly what happened at Sleepy Hollow, which helps to explain why the work on the main course turned out so well. Third, in Michael Hegarty first as Vice President and then President, and George Sanossian who was Green Chairman the majority of the time, there was continuity of club leadership liaising with the architect. Sanossian states, ‘When we started the work in 2006, we all got along great, there was a lot of positive energy but knowing how construction projects usually go, my concern was that we wouldn’t feel this way about each other when the project was completed and what a shame that would be. Happily, my concerns were merely that – and to the contrary, at the end of the project there was more respect and admiration among the team members than there was at the beginning.’ Many American clubs have a term limit for the green chairman yet most clubs are lucky if a ~ dozen members truly study and appreciate golf course architecture. Thus, quickly cycling through those that are knowledgeable seems like lunacy, especially as it goes hand-in-hand with changing directions and overspending. Ultimately at Sleepy Hollow, a small group of dedicated professionals and members came together to work on something they each regarded as very special, becoming friends and partners in an endeavor that in a slow, methodical manner, teased something remarkable from the landscape. It is patently not an oversimplification to state that when people enjoy the company of those with whom they work, joy can be found in the end product.

The top twenty courses from the Macdonald school of design are a special lot and include many of the author’s very favorite courses worldwide. Collectively, they represent the architect’s original design intent as well as any group of courses. Here’s the thing: when the author first saw Sleepy Hollow in 1985, it wouldn’t have even been on that list. Now, it would be in the top five, and that is after all the other courses have also had top flight work done to them. Talk about a transformation! It highlights the importance of exactly what good stewardship can mean to a club. Though Sleepy Hollow will never be the toughest or the most famous course in Westchester County, traditionalists have every reason to consider it now as inspiring as any course in the area for a game and should head straight there whenever possible.

GolfClubAtlas very much thanks Jon Cavalier for the use of his wonderful aerials in this profile. Please be sure to follow Jon and his work on Instagram @ linksgems for the best photographs in golf.

![The Park, West Palm (Lit 9) [2023]](https://golfclubatlas.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/IMG_7092-2-scaled-500x383.jpg)