Scottsdale National Golf Club

Arizona, United States of America

For those who cherish variety, The Bad Little Nine and The Other Course at Scottsdale National combine to provide Arizona’s finest playing experience.

Few people build a golf course. Therefore, few go through the process of hiring an architect and yet, imagining what the primary considerations are is not difficult. Two obvious ones are knowing that money will be well spent and that people will appreciate the result. Vital to the outcome is the interaction and chemistry between the owner and the architect, so the all-important question becomes: Who do you hire, knowing that everything that follows is a direct consequence?

The answer was once simple. From 1980 through 2000, a handful of name design firms enjoyed such clout to where each touched two hundred plus courses world-wide. When it came to big money projects, they essentially got all the work. In part, financing a project became easier by hiring a name. Interestingly enough, history hasn’t been too kind to many of those endeavors. To be fair, the vast majority of such projects centered around selling homes and when the residences went up, the fun went down. Plus, turns out when you hire a ‘name’, you hire his team, or one of his teams. The ‘name’ is busy traveling and keeping all his projects simultaneously on the go. Also, once the course is complete, you are now the proud owner of a course that might resemble ones elsewhere. Not so appealing, eh?

In this century, boutique firms emerged that do more hands-on, artisan work. Their total footprint might be 30 to 50 projects over a career. We are now twenty years into that movement and with many talented one and two man firms from which to select, the hiring process is anything but straightforward. Not many owners have the intestinal fortitude to give a young firm a chance given that tens of millions of dollars are at stake. One who did was Mike Keiser, when he gave an unknown (David McLay Kidd) the opportunity to build the first course at Bandon Dunes. Its success gave another relative unknown (Tom Doak) the opportunity to build a second course. Twenty years later, Keiser’s approach had changed resort golf in North America.

Few others have the wisdom/courage to take such chances but Bob Parsons is like few men. Whether founding Go Daddy or PXG, he has done it his way. In 2014, Parsons bought the Golf Club of Scottsdale. Shortly thereafter, he received a congratulatory email from Jackson Kahn Golf Course Design, a five year old firm. Its two principals, Tim Jackson and David Kahn, wished him well and informed him that they were hungry, local architects that would be delighted to assist in any manner with his new acquisition. Jackson and Kahn along with their friend Scott Hoffman had all trained under Tom Fazio and worked on several of his most acclaimed designs including Gozzer Ranch in Idaho, Pronghorn in Oregon, and the renovation of Shadow Creek. Jackson and Kahn set up their own firm in 2009 and to date, their highest profile win had been a redesign within the existing routing of the Dunes Course for the Monterey Peninsula Country Club.

Their email garnered them a face-to-face meeting with Parsons and the conversation quickly turned to what could be done with holes 15-18, which charged up and onto the mountain and made the course un-walkable. The fifteenth green especially was an unloved three tier creation where putts from the wrong tier routinely ended up sixty yards down the fairway. As Jackson and Kahn studied the design, they found lots of unused space between holes. They ultimately suggested to Parsons that the four holes be brought off the mountain. Additionally, they had found enough space to create a nine hole short course.

Parsons was intrigued. Though Jackson Kahn’s in-the-field experience was mostly under someone else’s banner, they appeared qualified. By hiring them, Parsons knew who he would be getting and who would be at work everyday. Plus, he liked the idea that he would end up with something original that differed from the other 185 (!) courses in the greater Phoenix/Scottsdale area. He was also aware of something that they weren’t: he was in talks with Lyle Anderson to acquire 223 acres of adjacent land.

Needless to say, when he broached the subject of building a new eighteen hole course and a nine holer, the firm was over-the-moon delighted. However, in one of their many follow-on meetings, they had a disagreement regarding the returning nines for both eighteen hole courses that ultimately had him saying thanks, but no thanks. Parsons then made several calls, including to another local architect, Bill Coore. Coore looked at the site but the timing was awkward. When he asked Parsons who else he was considering, Parsons mentioned Jackson Kahn and Coore responded enthusiastically, noting that he knew Jackson and was a fan of his work. He also mentioned that Coore & Crenshaw were ever so grateful for their very first opportunity and that every talented group had to start somewhere. Within one week, the project was Jackson Kahn’s! This wasn’t the first time that Bill Coore, ever the gentleman and with a wonderful eye for identifying talent, had gone to bat for another firm. Rod Whitman and Gil Hanse will tell you what a difference Coore has made to their careers in what is a cut-throat business.

Parsons secured the land from Anderson and Jackson Kahn quickly settled into routing 27 holes. They had precious few natural features from which to base holes; a few rock outcroppings and formations and some federally protected dry washes was it as the land was mostly flat and featureless. As they developed tentative plans, Parsons kept acquiring 5 or 10 or 15 extra acres here and there along the perimeter as a buffer. What a luxury this proved to be and the scale of the course kept expanding.

Parsons was after fun and variety and he defined that as every hole being memorable and free of outside intrusions. The architects pledged to him that no par would repeat. Also, to set the course apart from other desert courses, they wanted it to be walkable and for the experience to be a ‘quiet’ one. As opposed to being crunch, crunch, crunch off every tee, the course would enjoy continuous short cut from the first tee through the eighteenth green. Additionally, they envisaged creating the golfing ideal with holes rising and falling at least twenty feet to add to the variety/memorability.

The tempting comparison is to that of Shadow Creek in that the charge was to build something charismatic from a flat site but there was one main difference: Shadow Creek was intended to be an oasis while Parsons wanted his course to be true to the Sonoran Desert. Though he grew up in Baltimore, Parsons had long lived in Scottsdale, loved the area and his course was to reflect that devotion. Only vegetation native to the Sonoran desert would be utilized with the varietals of cacti comprised of saguaros, barrel tiny, jumping (or teddy bear) cholla, and staghorn cholla. Trees included Mesquites, Ironwoods, and Palo Verdes and they were augmented by low lying darker green shrubs like Creosote.

Earthwork contractor Constant Safe Work oversaw the 400,000 cubic yards of drill and shoot. Six hundred thousand cubic yards of ripple material was cut and bulked on site to build the mass terrain. Cook & Solis created the 30 foot deep, 23,000,000 gallon storage lake and set 20,000 tons of boulders. Once the earth works was completed, 110,000 (!) indigenous plants were field spotted by Pinnacle Design and Native Resources International installed them one at a time. That’s 90,000 1/5/15 gallon shrubs, 4,000 boxed trees, and 14,000 cacti which included some 1,200 saguaros. As if that wasn’t enough, two people with backpack sprayers then hand stained with Permeon all 20,000 tons of placed rock to instantly weather and age the look of the ‘freshly’ shot rock.

The real story isn’t that every inch was touched. Rather, it is the tasteful manner in which everything was assembled to create a special environment in which to enjoy the game.

The construction of the course itself fell to Landscape Unlimited. Of utmost importance, all the playing surfaces were sand capped, to the tune of 73,000 tons. One hundred and fifty thousand tons/110,000 cubic yards of total material was hauled to the site by 6,800 trucks, including the bunker sand and green mix. Thirty-eight miles of irrigation pipe were laid and 4,000 irrigation heads installed and enough irrigation wire (665 miles) was used to reach to The Golden Gate Bridge. To say this was quite the undertaking is an understatement.

While the above is truly impressive, remember that there is no shortage of ways to consume funds during course construction and still end up with something of no lasting merit. Tim Jackson sums up the project well when he says, ‘Resources alone don’t allow for great golf to be realized. There are many high profile, high dollar projects that fall short of the type of golf I think we would all consider to be engaging. Certainly, resources help, but it takes a tremendous amount of creativity as well to forge aesthetic, thought provoking golf from essentially flat terrain – and then completely hide the fact that you did so.’ So true, and you don’t have to drive far from Scottsdale National to realize the validity of those words.

… Jackson Kahn and Hoffman envisaged the short 140 yard 11th. They created its own secluded valley and raised green, which at 4,042 square feet is the course’s smallest target.

Today, the 11th is as pretty as a postcard, helped considerably by the random rock placements and indigenous plantings.

Work commenced August 10th, 2015 and was open for play on October 29th, 2016. The net effect is that one assumes Parsons instructed Jackson Kahn to find the ideal golf site in the greater Scottsdale area versus the truth of transforming featureless land that bordered his eighteen hole course. The irony is that those involved will never get credit for their work because it looks like they were given a dream site with which to work!

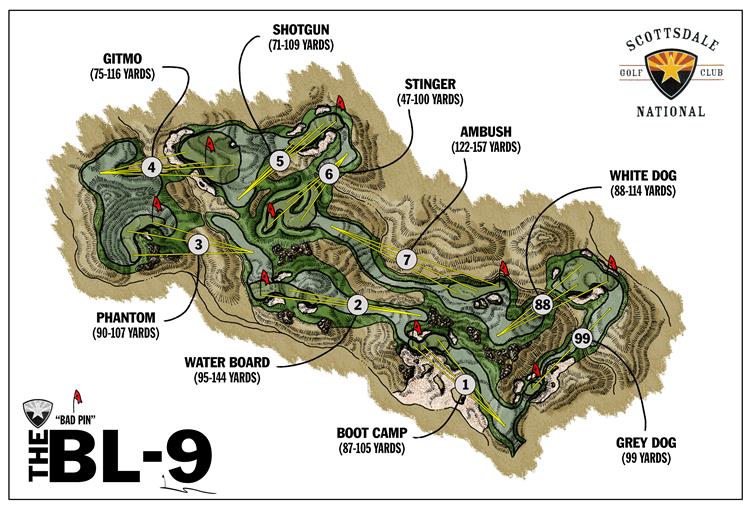

Included in this transformation were 17 acres for The Bad Little Nine. Measuring 972 yards, this par 3 course is something altogether more than a warm-up or warm-down round. Indeed, the architects pitched to Parsons, an ex-marine, that the nine should be in spirit like a marine obstacle course – and he agreed. Given how the obstacles are in your face, at some point, adversity will befall the golfer and the mental toughness that the player demonstrates in such situations defines the experience.

Though similar in length to The Cradle in Pinehurst, its purpose was different. It wasn’t built to cater to all, from youngsters learning the game to the elderly; in fact, its hazards are among the most penal the author has seen as a set. Particular favorites include several trench-like bunkers whereby a good stance and free swing are anything but a given. They remind the author of hazards captured in pre-1900 paintings of links like Carnoustie and Prestwick. The notion of ‘fair’ mercifully didn’t exist back then and as such, these bunkers are a reminder of days long gone where hazards lived up to their name and were things to be avoided.

This view is across the 6th toward the 5th green. Given the close proximity of the holes on The Bad Little Nine, an appealing sense of camaraderie is created for golfers that is often absent on large scale courses.

Hole to Note on The Bad Little Nine

Second Hole, 126 yards, Waterboard; Not unlike what Raynor did at Monterey Peninsula, Jackson Kahn take the golfer higher with each of the first three holes, with most flowing downhill thereafter. The problem here is that the back quarter of the green actually falls away from the player. Anyone who has played Oakmont knows the consternation that can cause and it is no different here.

Fourth hole, 104 yards, Gitmo; The greens vary wildly in size. This one at over 10,000 square feet is the largest while the last hole is less than 1/10 the size! However, that is not meant to imply that the fourth is somehow a breather. Just the opposite as along the right of the green is one of those appealing trench-like bunkers that narrows to less than two feet in width. Today’s routinely pampered golfer assumes that it is a birthright to enjoy a straightforward recovery shot but that notion comes to a crashing halt here. A nine holer with bland hazards and flat greens would hardly inspire participation; the task for Jackson Kahn was to provide temptation by striking the right balance between risk and reward. This large target with a particularly nasty hazard creates the perfect amount of playing tension.

The soft roll of the putting surface adeptly sheds slightly under-hit balls into the trench right of the green.

Fifth hole, 86 yards, Shotgun; Most conventional hazards sink into the ground but here, knobs rise two and three feet and pose a different set of problems. In particular, a clump of dirt was piled into the middle of the putting surface and grassed over. All the hole locations orbit around it and two things are apparent. One, the challenge of the hole clearly changes each day with the movement of the hole location. And two, the golfer is left wondering why this tactic can’t be applied on courses elsewhere?!

The clump in the middle works with the back right shelf to make this hole location a testy proposition.

Eighty-eighth hole, 88 yards, White Dog; With a short iron in hand, the golfer’s psyche tells him to attack! Maybe he bites off a corner of a dogleg on a two shot hole or perhaps he hits his second shot within 80 yards of a green on a three shotter. Regardless, he takes risks to be rewarded with a short iron to a green. That mindset can pay off when greens aren’t as well defended as they are here but don’t let the fact that you are playing a par 3 course provoke rash and unwise decisions. If anything, the golfer needs to be more tactical, not less, and make better decisions than he normally would on a regular length course. The need to be prudent is born out in the pictures below that show the far back left hole location on Challenge Day. Augmented by the view of Superstition Mountain in the distance, this hole is a favorite of many. Its sweeping green contours yield both the easiest location (front left and thoughts of a hole-in-one emerge) and hardest (back left and one might not finish) on the course. The golfer has taken ~30 minutes to reach this spot and clearly, he has needed to be focused from the get-go. Given the appealing pressure applied to his game and the compressed time between shots, he can be forgiven for wondering if there is a better use of his time in the state than these nine holes.

Challenge Day at Scottsdale National! If ever a picture captured the essence of each Friday afternoon’s Challenge Day, this is it. People prone to taking themselves and their precious game too seriously might self-combust.

The flexibility in course set-up is one of The Bad Little Nine’s great virtues. Move this hole location fifteen paces forward into the lower front bowl and the day’s average score falls by more than one full stroke.

Ninety-ninth hole, 99 yards, Grey Dog; At 900 square feet, this is the smallest green that the author has seen in North America on a quality course and it is made even smaller by its perched knob of a green pad. While the sixth green at the Isle of Harris in Scotland is similar in size, it is located in a semi-punchbowl where good news events can take place. Not here. In fact, this hole is so prickly that the first timer enjoys an advantage over the scarred member. There is no ‘safe’ way to play it, which makes it a fitting conclusion. Of course, too many such moments and the golfer with pride might shy away from The Bad Little Nine but here on the last hole, with everything at stake, the golfer yearns to execute. Hitting the minuscule target is tough for even wedge master Zach Johnson. What’s really tough though is your second bunker shot!

True, The Bad Little Nine can overwhelm a certain type of player but that is so by design. The owner wanted an obstacle course that would tax the player, even though the longest hole is a mere 153 yards. And that’s what he got, all without water. The ability to play the course frequently would sharpen not only one’s wedge play but also one’s ability to recover. Additionally, where to ‘miss’ the ball is crucial – long on the first, short on the second, right of the fifth, long left on eighth simply won’t do. Therefore, one’s ability to assess properly different situations including when/where to aim away from the flag is an underpinning of success. How many sub-1000 yard courses require such clear thought and crisp execution? Any?

When all is said and done, it is a par 3 course and you are free to ‘go for it.’ You can be handsomely rewarded by flirting with disaster or savagely punished and it highlights what a pity it is that so many courses – par 3 and otherwise – feature milquetoast hazards and greens that fail to inspire and capture the imagination. The key thing heading in is that you will either possess the ability to laugh at your shortfalls or you will learn to have the ability to laugh at your shortfalls by the end. After all, if you don’t have a sense of humor, for goodness sake, don’t play golf, which humbles even the very best.

The only notable design aspect lacking on The Bad Little Nine and its tightly defined targets is a lack of ground game options. Of course, given that each hole averages 108 yards, so what? Plus, that wasn’t the mandate. Nonetheless, walking the 100 yards from the ’99th’ green to the first tee of The Other Course, the first time player might wonder if more of the same is in store. The answer is ‘no’ and much to the credit of Jackson Kahn, the opposite holds true as they built something with wildly different playing characteristics while still remaining true to the Sonoran Desert.

In fact, The Other Course features shots tailored for the ground game. Even better, Parsons endorsed not over-seeding The Other Course. Therefore, when the Bermuda fairways go dormant heading into the playing season of early November, the fairways become ‘white lightening’ and ground game options flourish. This is how a club should be run and the golf structured. The original course (now called the Mineshaft) is over-seeded with rye and features the sort of target golf that made Arizona famous world-wide. The Bad Little Nine is its own, spuddy creation and The Other Course is altogether different again. The three distinct offerings cover whatever challenge a member is seeking that day.

Desert Forest, the Grand Dame of desert golf, made a name for itself by not over-seeding for the first four decades of its existence. Alas, it succumbed in recent times and started to present its course in the conventional manner with rye grass in the winter. According to several past members, the course (and club) lost a bit of its identity when that occurred. Parsons’ The Other Course stands out for offering dormant Bermuda fairways in the greater Scottsdale area. Dormant Bermuda is an ideal playing surface as it can be quite bouncy-bounce under dry conditions. Arizona provides that very thing and with limited play (and therefore limited carts), The Other Course is perfectly suited for that playing surface.

The author played here in mid-October, just before the Bermuda became dormant. Nonetheless, the fairways were fiery and all shots available to the player. Kudos to Green Keeper Rick Holanda and his crew for the job they do. Interestingly enough, Kahn and Hoffman recommended Holanda for the project. They first met him in 2007 at Shadow Creek and Holanda went on to oversee the Bermuda grow-in of a high profile Fazio course in Brazil. Hiring the architect is one thing but without the right Green Keeper, the pleasures from a design can be muted. Give Parsons credit for getting both hires right, as we see below.

Holes to Note – The Other Course

Second hole, 545 yards, Harris Hawk; The concept of strategy – of making each shot matter relative to the next – was at the forefront of this design. Without it, the course would fail to hold Parsons’ interest round after round and the project would be deemed a failure. Of course, making every hole require its own set of thought processes is no mean feat. At the second, a protected wash acts as a central hazard as it stretches across the fairway some 150 yards from the green. Carrying that in two is the goal but just finding the 70 yard wide fairway beyond isn’t enough. The golfer needs to pay heed to where the hole is located on the 9,000+ square foot green, as we see in the photographs below.

When the hole is left, the golfer needs to lay up long right and vice versa: when the hole is back right, the golfer needs to lay up short left. It’s the …

… classic X pattern with the day’s hole location determining which side of the fairway one should approach the green. Indeed, the proper layup spot can shift by ~50 yards from one day to the next and instilling the course with such playing angles was crucial to the project’s success.

The cantankerous back right hole locations are jealously guarded by the false front and are pricklier to get near than the front and central hole locations. Short grass and ground game options are already making their presence felt.

Third hole, 200 yards, Bobcat; This is the first of six one shotters, each nicely spaced in length from the others. From the 6,777 set of tees on which this profile is based, the six holes measure from shortest to longest the following yards: 134 – 145 – 158 – 171 – 200 – 215, ensuring a broad range of clubs will be used. As a side note, every course has shifting moods as the sun moves across the sky but that seems to hold particularly true at Scottsdale National. Landforms that are 3 and 5 and even 20 miles away become illuminated by the rising or setting sun. The eye can’t help but wander and soak in the different desert hues and colors. Such attractive long views afforded while playing The Other Course aren’t by chance. Jackson Kahn and Hoffman didn’t route the course from a computer; they were continuously on site, tweaking the playing corridors to showcase as many of the distant peaks and mountain ranges as possible.

As seen early morning, the eye rotates between the attractive golf scene in the foreground and the Mazatzal Mountains 12 miles in the distance. A very special thank you to Gary Kellner of Dimpled Rock Photography for the liberal use of his striking photographs that populate this profile.

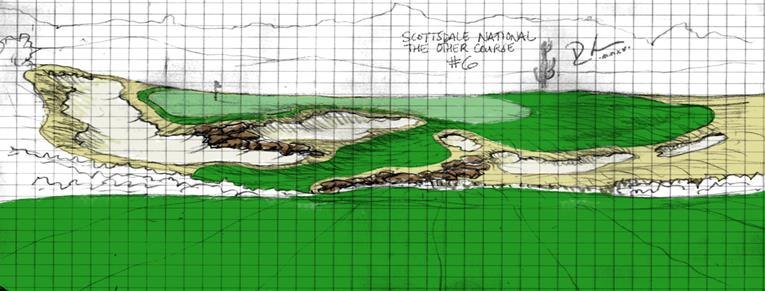

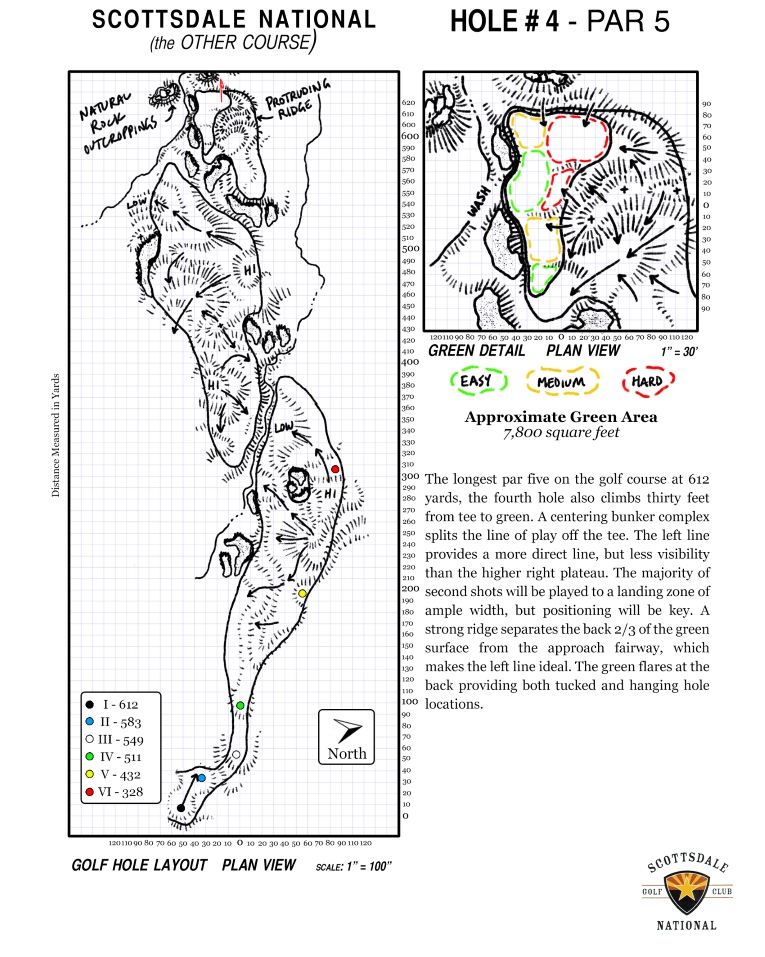

Fourth hole, 555 yards, Mule Deer; Look at the initial drawing below. What’s not to like?! Tick through the admirable design features: lumpy fairway, central hazards, playing angles, green bunkered on only one side, and a ridge that creates a punchbowl effect on the other. Add them together and good golf qualities were breathed onto what was previously a benign desert floor. The punchbowl created back right is an unusual – and potentially player friendly – feature to find in desert golf. Its use of short grass to both help and befuddle the player makes this one of the author’s handful of favorite holes. In fact, it is worth pointing out that all of the three shot holes are included under Holes to Note. Most modern architects labor to come up with just one or two appealing three shotters per course; Jackson Kahn came up with six (!) at Scottsdale National.

At ground level, the architects provide lots of short grass right though often times, the golfer needs …

… to stay left. This view from back right of the green captures the novel punchbowl feature now found in the Arizona desert.

Fifth hole, 475 yards, Buzzard; After Parsons obtained the primary land block, he acquired smaller parcels around its perimeter and some of these parcels possessed natural topography, such as here where a fifteen foot foot rise existed across a shallow valley. So what did the architects do? Nothing, other than to make sure they incorporated the landform into the hole to create a fine, blind tee shot. Once over the hill, one of the great creations unfolds: the monster 21,000 square foot fifth green. Isn’t it interesting how so many world-class long two shotters – Sea Headrig at Prestwick, the sixth at Royal Melbourne, the opening holes at both Oakland Hills and Winged Foot, etc. – end at savage greens? Modern convention has too many of today’s architects playing it ‘safe.’ Here, on the longest two shotter on the course, the architects built arguably the course’s wildest green – and history says they join good company in so doing.

Many of the great all-time architects struggled to break 80 on a consistent basis. Nonetheless, being a great player doesn’t preclude one from being a great architect. Tim Jackson, David Kahn, Scott Hoffman, and design associate Calan Hoppe play to a combined handicap of 1 (!). Above, they test drives from the 520 yard back tee of the 5th.

This aerial highlights the natural landform that was exposed and captured within the confines of the 5th playing corridor. The club’s expansive buffer is also evident.

The entire 5th green fits in the photograph largely because it is taken from 160 yards away. The fact that the green rises over nine feet from front left to back right hints at the magnitude of this spectacle, which is made even more herculean by the absence of framing.

The short bunker was employed to perfection to confuse and obfuscate. On a tour of the course as it was taking shape in the dirt, the architects brought Parsons to this fairway some 220 yards from the green. The forms were in place but there was no grass nor bunker sand nor flag. They asked Parsons how far they were from the green center. He guessed 150 yards and when informed of the delta, he was intrigued to the point where he asked what it would take to continue the optical deception. One thing they suggested was an abnormally large flag and to this day, the flag on the 5th green is 3 times (!) the size of a normal flag.

Sixth hole, 170 yards, Dragon Fly; More than any architect firm with which the author is familiar, Coore & Crenshaw popularized the concept of a boomerang green. George Thomas was a fan too as this type green – wider than deep with a bunker pinching into its middle – inherently renders a number of interesting hole locations. This version though is the rare time that the author recalls seeing it deployed on a one shot hole.

At over 13,000 square feet, the uber-wide 6th putting surface makes greens on most other courses look dull and tedious. Today’s right location is deceptively annoying, thanks to a false front.

Note the interesting change that occurred in the field, namely how the central front bunker shrunk in size. The small pit seen in the first photograph above is assuredly harder from which to recover than the large swath of sand originally contemplated.

Seventh hole, 385 yards, Gray Fox; As previously noted, variety was baked-in at the start by the architects’ pledge to Parsons that no par would repeat. Yet, that could be superficial if the targets and asks of the golfer were somehow similar, regardless of par. Let’s examine the past four greens to determine if variety permeates. There is the sunken fourth green, a punchbowl of sorts that measures just over 5,700 square feet which is followed by the monster fifth high on a plateau that is almost four times (!) larger. Then the one shot sixth with its imaginative horseshoe green. What follows? The second smallest green on the course, a teardrop shaped putting surface barely over 4,000 square feet. It is a fitting end to this drive and pitch hole as the petite target looks even more undersized after the prior two colossal greens. Was Parsons’ request for variety and memorability honored? Yes. Interestingly enough, when pressed for an answer, both David Kahn and Tim Jackson nominate the approach here as one of their two or three favorite shots of the round. Yes, the holes on either side feature more ‘spectacular’ qualities but the exactitude of this sleeper approach shot grabs many an unthinking player.

Hitting the diminutive 7th green is made even more elusive by the fact that the golfer is likely to approach it from a sidehill stance.

Eighth hole, 540 yards, Road Runner; There are hundreds of desert courses, the vast majority of which the student of architecture need not bother seeing. Only a handful including Apache Stronghold, We-Ko-Pa, and Talking Stick provide classic design features and the student delights in observing how such features were transposed to the desert environment. Scottsdale National joins that short list and this hole exemplifies the Golden Age axiom of ‘defending par at the green.’ Having said that, merely replicating Golden Age design principles would not have yielded the kind of originality that Parsons sought. The principles needed to be applied with creativity and one look at this green with its gull wings and sunken front cavity confirms that they were. Though a majority of the playing season features less than a club of wind, when it blows, it comes from the west, which means this hole is downwind. One of the architects joined seven players from a top ranked ranked college golf team during their round here. They had the course to themselves and were playing as an eight-some. Played from the back markers, dead down gale, they all drove it over 400 yards, leaving them ~150 yards in. The flag was on the high left plateau and the architect advised everyone to aim for the middle of the green, two putt and head to the next tee content with a birdie. Alas, prudence rarely follows a 400 yard drive and the ace players chased after the hole. The common outcome was that most hit the putting surface only to see their balls bound into the waiting back bunker. One of the seven secured his birdie. The eighth – the architect – played for the middle of the green and got the only other birdie.

Given the firm and fast conditions as provided by Green Keeper Rick Holanda, the golfer should find himself in range of this roller-coaster green in two.

The ball at the base of the green was struck from 240 yards out, landed short, climbed to within 20 feet of the hole for what would have been a potential eagle putt, tittered, then … rolled back. The ensuing three putt highlighted that par had indeed been defended at the green.

Ninth hole, 145 yards, Catfish; By the end of the front nine, the golfer assumes that each view from the tee will be compelling; long forgotten is the fact that the land was flat and featureless. And sure enough, standing on the ninth tee and looking across the valley at the green tucked in its own amphitheater, the big picture stuff is once again enthralling. However, what about the golf itself? Just how good is the shot itself? That’s what matters – regardless of the course’s origins, we are here to play golf and is the golf as compelling as the environment? Once again, the answer is yes.

One of the course’s most fun shots is on offer today. Specifically, the golfer can play his tee ball high right of the green and watch his ball deaden, take the slope, and then trickle sideways close to the hole.

Tenth hole, 535 yards, Gila Monster; Restraint plays a vital part in great architecture. If the architect crams too much into every moment, the golfer’s senses numb. This ‘trap’ of trying to dazzle must have been acute for Jackson, Kahn and Hoffman. First, they reported to one man and they surely wanted to impress. Second, with Parsons’ resources, the three had everything at their disposal. What about a 40 foot waterfall? What about this and that? Any and everything could have been built. Yet, they didn’t and one of the best examples of putting the golf first occurs over the last fifty yards of the tenth hole. A reachable par five, the potato chip, wavy green is surrounded by short grass with the nearest bunkers ten paces removed from the putting surfaces. True, the bunkers play bigger than they are as gravity feeds balls into them. Nonetheless, the green complex doesn’t scream at you – and the course is all the better for it.

As seen during grow-in, the triangular 10th green middle left floats in a sea of grass. Meanwhile, the tightly bunkered 11th plays in its own corridor and couldn’t be more different.

Eleventh hole, 135 yards, Blind Squirrel; Tim Jackson, David Kahn and Scott Hoffman are grateful for what they learned while working for Tom Fazio and they certainly appreciate the role that aesthetics play in the overall experience. Thus, the three men spent a lot of time on the composition of each hole. Parsons got what he bargained for in that the three men were on site 6 1/2 days out of the week during the fifteen month build process. That kind of time on site directly led to many postcard worthy moments and more importantly, to so many holes that play as good as they look, including here.

The architects seized advantage of the opportunity to build a tiny target, knowing that the course would likely receive less than 5,000 rounds per annum. A hole like this would be a poor fit on a heavily trafficked resort course.

Twelfth hole, 395 yards, Coyote; Desert golf can be fairly straightforward: hit it anywhere but the desert! Therefore, it is refreshing to find a course like The Other Course where the golfer is given gobs of short grass and the question shifts from what not to do but rather can the golfer discern what to do. The twelfth is one such hole and it descends worry-free downhill to one of the course’s widest fairways, stretching 130 yards (!) from side to side. Not that there are any cramped moments at Scottsdale National but this is an especially fine time to swing out. Of course, complications ensue. One is the lumpy fairway, where the more level lies are afforded only to those that steer right of the green off the tee or lay-up short down the left; those that bomb away directly at the flag are guaranteed a hanging lie. Additionally, the hole location on the triangular green has a great deal to say as to where one should place the drive. Essentially, the twelfth is wildly irritating in that the architects provide more than ample room and in so doing, they analyse the golfer’s mind. The resulting report card is often unflattering.

The day’s hole location dictates what part of the immense 12th fairway the player should seek from the tee.

Fourteenth hole, 470 yards, Javelina; Was all the earth works warranted? That is tantamount to asking, did it create a special environment and did it add to the golf? As to the first question, the photographs included in this profile speak to that. As for the second question, the golfer standing on the fourteenth tee sees a sloping hillside with a small pit carved into it. A big thump with the driver will have the golfer over it and if he is bold enough to clear the highest point of the slope, he is rewarded with the ideal angle into the green, which is of the pushed-up variety. Putts from above the hole jangle the nerves of even the smoothest putters. From flat land emerged a memorable blind drive over the brow of a hill and another green pad that rewards proper placement. Did the earth works enhance the golf? You bet.

… as that line leaves the golfer looking up the spine of the green, as captured in this photograph from Gary Kellner’s drone behind the green. The hard, offset nature of the front left bunker works in concert with the tee ball to create the hole’s playing interest.

Fifteenth hole, 600 yards, Rattler; The word ‘journey’ cuts both ways. Depending on the state of one’s game, it can mean something long and arduous or if by some miracle the swing is cooperating, it can portend a grand adventure. So it is here with the golfer hoping his game holds up in the later stages of the round as he needs to hop, skip, and jump across various features on this admirable, rambling three shotter that bends left off the tee and heads toward Cholla Mountain. The fifteenth exemplifies that hazards directly in the line of play are far more satisfying to conquer than those meaninglessly found on the sides of fairways as on so many other desert designs.

If successful, the final task is a pitch over a federally protected 404 natural wash. Of note, the first four par 5s are quite receptive to running approach shots from ~240 yards out while the final two feature greens that are sealed off across the front.

Sixteenth hole, 160 yards, Yellow Jacket; The sixteenth tee happens to be one of the prettiest spots on the property to the point where the golfer may be lulled into a false sense of comfort with harebrained decisions soon to follow. After all, the hole isn’t terribly long and the green is over 9,000 square feet. What could go wrong? Several things. The imaginative use of islands in the great fronting hazard stimulates less than straightforward recovery play. Having lost that battle more than once, the member naturally steers away. Yet, the oblique angle of the green to the tee makes it a more slender target than one realizes. A shot that drifts just a bit long is carried away by short, tight grass, leaving the golfer an uphill chip … to a green that speeds away … toward the very hazard he sought to avoid. It is a great match play hole – and it is aptly named too – as the hole can sting.

The last of the six one shotters is every bit as hard as it is handsome. It is no accident that the green pad was built up just the right amount to show off the Superstition Mountains in the distance. Weaver’s Needle is the jagged point left of the flag.

This October 2018 photograph shows how the desert floor plantings have filled in nicely in just a few years.

The green is big and the bunker is larger but it is the slope away from the green on the left that can undo the player.

Seventeenth hole, 300 yards, Butterfly; The initials for The Other Course are T.O.C., which also happen to be the ones for the The Old Course at St. Andrews. Aesthetically and chronologically, the two couldn’t be more different but from a design philosophy perspective, similarities are rife. Both enjoy memorable hazards that punctuate wide fairways and immense, rolling greens. The first and last fairways are shared. Both are spacious enough to allow all caliber of players to enjoy themselves by tacking around the hazards, and the art of the recovery shot is alive and well. The set-ups are enormously flexible: when hole locations are moved to the more vexing perimeter locations, even the tiger struggles at both. The penultimate hole at T.O.C. in Arizona reminds the author of an amalgamation of the irritating qualities of the drivable tenth and twelfth holes at St. Andrews. One would like to think that a three could be had but more times than not, that proves to be wishful thinking. What a great place in the round to find a hole of this length.

The start of the gigantic central bunker is 60 yards from the front edge of the putting surface. Meanwhile, …

At a whooping 15,535 square feet, the 17th green poses the same time honored challenge as those at St. Andrews and Yale, namely, can the golfer get his second shot close when the target is so large?

Eighteenth hole, 570 yards, Mountain Lion; As we have seen numerous times, the three architects delight in providing temptation with the fruit just out of reach. The final drive is fittingly blind over the crest of a hill and sure enough, that implies that the tee ball will receive a helpful scoot forward, thus bringing the green within reach. As he crests the hill, an alluring scene unfolds below with the green nobly offset by sand and rock, the PXG clubhouse in the near background and the Mazatzal Mountains and Four Peaks in the distance. And yet … now what? The golfer might be within reach of the green with a 3 wood but almost assuredly, he will be striking the blow from a slightly downhill stance. Muddling matters, the green is tightly bunkered front and left and the putting surface is one of only a handful that measures under 6,000 square feet. Should one have a go? Perhaps, especially as an up and down isn’t unreasonable from the front bunker. Creating further uncertainty, the architects smoothed over a patch of fairway some 80-100 yards from the green. A near perfect stance is afforded there and the pitch is within most golfers’s ability. Which tactics – aggressive/attacking or thoughtful/prudent – are better rewarded over a playing season? The jury is still out. One thing is for sure: the tempting questions it poses are a microcosm for the rest of the design and highlights why this is a course that you would like to play all the time as you can’t help but enjoy your chess match in the desert with the architects.

As seen from 240 yards out, can the golfer get enough height off with his second to hold the green? Or …

What a day of golf. The Other Course couldn’t be more different than The Bad Little Nine. It is ‘inclusive’ architecture whereby literally everyone can have fun while The Bad Little Nine thrives on its pugnacious nature. Good on the owner for wanting two distinct offerings and on the architects for seamlessly delivering. A drink by one of the fire pits concludes an exhilarating time.

Given the backdrop of being built from nothing, comparisons to Shadow Creek are unavoidable, especially given the Jackson Kahn relationship with Fazio. Kahn and Hoffman even worked on the 2007 renovation of Shadow Creek. Big picture, similarities abound in that both are feats of engineering whereby a beautiful golf environment arose from a flat, featureless landscape. Rick Holanda was the Green Keeper at both. Two strong-willed owners each got what they wanted. Neither Shadow Creek nor Scottsdale National are crowded and even if they were, the golfer is more times than not cocooned in his own playing corridor while still enjoying views of distant mountains. In terms of differences, the holes at Scottsdale hit the ground in a greater variety of ways. When the architects had a rare chance to naturally find an ‘up and over’ hole like at the fifth, they did. When they didn’t, they created many fine blind drives including at the eighth, fourteenth, fifteenth and eighteenth. Additionally, there are more central hazards at Scottsdale National. At the greens, the putting surfaces at Scottsdale National are more diverse than those at Shadow Creek but that’s true over almost any course one can name. After all, how many courses feature greens that range in size from 4,000 to 21,000 square feet, where two of the greens (e.g. the fifth and eighth) have changes in elevation more than a man is tall, where one is a semi-punchbowl (e.g. the fourth) and where another features a horseshoe configuration?! Overall, out of ten rounds, the author would divide his time seven rounds at Scottsdale National and three rounds at Shadow Creek.

What lies ahead for Jackson Kahn? Hopefully, plenty as they marry an appreciation of strategic golf to aesthetics. Kahn’s favorite architect is Mike Strantz who took chances and didn’t pander to everyone’s sensibilities. Kahn points out that all great holes from the Road Hole to eight at Pebble Beach feature unconventional elements and that architects need to take chances. Kahn notes, ‘While we are very appreciative of what has gone before us, our goal isn’t to replicate what has already been done. We strive to put our own stamp on things and if we are successful, perhaps others will ultimately want to borrow from our work.’ That kind of creative mindset has the author keen to see what follows.

Hats off to Parsons for giving Jackson Kahn such a grandiose opportunity. Few people would have had the guts to trust a young firm with such a massive undertaking. Just like PXG makes ‘clubs unlike any other’, Jackson Kahn created courses unlike any other – and golf wins.

GolfClubAtlas again thanks Gary Kellner with Dimpled Rock Photography for the use of his photographs throughout this profile.

![The Park, West Palm (Lit 9) [2023]](https://golfclubatlas.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/IMG_7092-2-scaled-500x383.jpg)