Prestwick Golf Club

Ayrshire, Scotland, United Kingdom

Over 150 years after the Keeper of the Green Tom Morris Sr. laid out twelve holes, Prestwick still defines the essence of great golf.

The stamp and Morse code had recently been invented; the telephone and light bulb had not. The New York Times was a few months from being founded and Big Ben was eight years away. Yet golf was being played at Prestwick in 1851. Ever since, grand feats have been accomplished on these grounds including a three by Young Tom Morris at the original 578 yard first hole, with a gutta percha ball no less! A club of Prestwick’s pedigree would be a standout solely on a historical basis. After all, it hosted the first Open Championship in 1860 and twenty-four more (!) through 1925. However, it is far more than a historical footnote because a round of golf here today still embodies the very finest attributes that the game has to offer.

Indeed, what makes it so outstandingly fresh and invigorating to play here is that the club never capitulated to passing fades and fancies. Except for the odd occasion when it has been for the best to conform like agreeing to a standard of eighteen holes, the club has expertly avoided change for the sake (perceived) of remaining relevant. Other clubs might have lowered sand dunes here and there to eliminate blind shots, lessened the steep tilts of the ninth and seventeenth greens, given the golfer a more realistic target at the thirteenth, propped up the right side of the fifteenth green or the rear of the sixteenth. Not Prestwick. As a result, Prestwick reminds the golfer of no other course in the world. Its peculiarities are wonderfully all its own and the club should be celebrated for carrying forward the best playing values since the dawn of competitive golf.

Each and every round at Prestwick unfolds in a way that can’t be anticipated; both good and bad breaks occur with alarming frequency. How the golfer handles such moments, such serendipity speaks volumes. Fortune turns some golfers churlish and others steely. The point is that Prestwick tests the width and breadth of a man both physically and mentally. Such a thorough examination distinguishes a course and in the case of Prestwick where it has been performed so eminently for so long it signifies greatness.

To appreciate Prestwick today is to understand its three stage evolution. Under Old Tom Morris’s stewardship it began as a 12 hole course with holes zig-zagging across each other over 50 acres of some of the best landforms the game has ever seen. The second act began in 1882 after the game became standardized to eighteen holes when Prestwick’s long time professional Charles Hunter reconfigured the course and added six holes. He headed north of an old boundary wall that once ran behind today’s third green and gave birth to several of Prestwick’s most notable holes including the first, fourth, and fifth. Bernard Darwin – not surprisingly – described it best in 1910 when he wrote in The Golf Courses of the British Isles:

Nowhere is to be found a more beautiful stretch of what is called “natural golfing country.” The ordinary golfer, whose head is not too full of modern architectural ideas, would jump for joy on first beholding Prestwick. There is nothing subtle or recondite about it; it has a beauty which explains itself. There are great sandhills bristling with bents and little nestling valleys beyond them, a rushing burn, and a stone wall, and it is perfectly clear that a man was meant to hit the ball over them.

After the stretch of holes 7 through 11 came into its final form in 1922 with work by James Braid and Harold Hilton, the evolution was complete. At this point, all of today’s playing corridors and greens were in place.

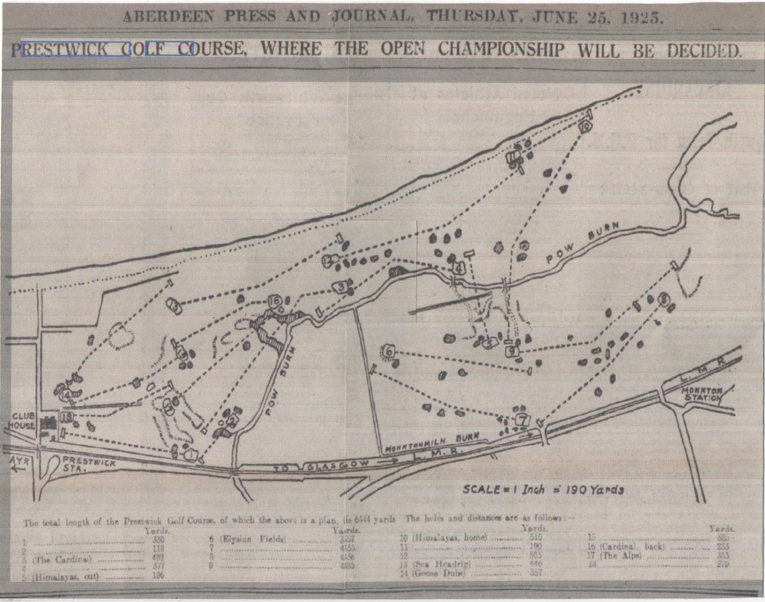

Old Tom Morris’s great great grandson Melvyn Morrow provides this 1925 diagram from the Aberdeen Press and Journal.

While the first stage lasted 31 years and the next 40, the holes now in play have been so for more than 90 years with only tees being pushed back. Throughout this three-act saga Prestwick regularly identified the most complete golfer. The winners of the Opens and Amateurs held here are a who’s who of champions: Old Tom Morris, Young Tom Morris, Harry Vardon, Willie Park, and John Ball are multiple victors, and Willie Park Jr., Laurie Auchterlonie, James Braid, and Harold Hilton also entered the winner’s circle at Prestwick. The list goes on to include the 1952 Amateur champion, Harvie Ward, certainly the best amateur and perhaps the best player of his day. The phrase ‘Champion Golfer of the Year’ was born here – and it’s easy to see why!

Old Tom Morris’s original twelve hole course was confined to a compact area owned by the Earl of Eglinton. Fortunately, it was superlative land and Old Tom Morris’s work allowed Prestwick to establish a formidable reputation from its origin. Many sterling holes arose within these mighty, choppy dunes and six of Old Tom’s greens are still in use to this very day.

While the sandy turf is equally delightful north of the wall, the landforms are more restrained. Hence, the holes that fall over this broad, graceful tract are more conventional with one exception (as we will read later). Sometimes wrongly vilified, the stretch of 6 through 10, all 2-shotters, deserves its own commentary. Averaging a whopping 455 yards, these five holes aren’t what make Prestwick beloved but they play a vital role in insuring that it remains a varied and enduring test for the world’s best amateurs. A walk among them reveals holes of character and great challenge. The sixth features a green that is partially obscured behind a hillock with a steep embankment behind. The seventh, eighth and ninth vaguely triangulate and house nearly one-third of Prestwick’s 102 bunkers. Especially memorable are the steeply pitched back to front green at the eighth and the wicked left to right side slope at the ninth green. With its tee high on the Himalayas range providing views out to the Isle of Aaron, the tenth is the most scenic.

Influenced by his mentor Old Tom Morris, Charles Hunter wasn’t afraid to create wicked slopes and contours within his putting surfaces. A green like the ninth with its sharp fall off to the back right becomes particularly devilish at today’s green speeds.

High on the dune, the eleventh tee is the closest point to the Firth of Clyde and the long three shot twelfth takes the golfer back south of where the wall once ran. From there, the golfer plays home over the some of the game’s most hallowed turf.

Built in the 1920s, the eleventh hole is a collaborative effort between James Braid and Harold Hilton that features a canted green from right to left. When the wind blows off the firth on the right, the need to properly flight and shape one’s tee ball becomes paramount. Links courses pose such time honored tasks and great golfers rise to the occasion.

The Royal Troon clubhouse is seen to the north from the eleventh tee. Hunter also played a role in that famous course’s design evolution.

Prestwick hosted the last of its twenty-five Open Championships in 1925. Soon thereafter, the world became a gloomier place from economic woe and global conflict. After WWII, the bulldozer became integral to golf course construction. Land was shaped and shaped … and shaped. At some point, certitude became the goal; if a golfer hit shot A, he would get result B. Golf became formulaic and banality followed.

Courses built in the 1960s and 1970s were much of the same muchness. The marked exception was Pete Dye’s work; Crooked Stick, The Golf Club and Harbour Town established a new direction in architecture. These courses featured railroad ties, greens that came in a variety of shapes and sizes and quality golf that didn’t rely on length. Where did Dye develop these concepts, which bordered on revolutionary? Dye’s revelation came during a visit to Scotland in 1963 with Prestwick making a dramatic impression. Prestwick’s reach remains as persuasive today as ever. When he was building Cabot Links on the west coast of Cape Breton Island in Nova Scotia, golf course architect Rod Whitman was influenced by Prestwick’s classic features. For instance, Whitman freely acknowledges that the humpy bumpy terrain left of the third green at Prestwick was fresh in his mind when he shaped similar mounds left of the par 5 sixth green at Cabot.

And so it is and always has been: Prestwick dramatically and vitally influences the direction of golf course architecture. Only a handful of other courses can claim such a prominent role. Beginning with the seminal work of Old Tom Morris, Prestwick has always led. It contains EIGHT holes that have made a major impact on architecture (read below) – 99.99% of courses have none. Think about that!

Holes to Note

First hole, 345 yards, Railway; Only at Prestwick can a hole built in 1882 be considered new! Like the opening shot at Royal Liverpool it’s best that one gets the first swing done with before thinking too much, less paralysis set in. The famous stonewall, denoting out of bounds to the right, induces the most fear. So too does the fact that there is no practice field. The first swing is likely to be a stiff, cramped effort. Strong players might hit as little as a mid-iron off the tee. That’s the beauty of the course: you can never take anything for granted. Far too many courses enable the golfer to always reach for the driver. Less thought and care are required at such courses and the mindless golfer is allowed to settle into a comfortable routine. Not Prestwick! Ahead, the green is indicative of Prestwick’s ultimate trump card: a superlative set of varied putting surfaces. Some are severely sloped and others, like the first, feature imaginative random rolls and contours, none of which were shaped by heavy equipment. While Old Tom Morris’s greens (the 2nd, 3rd, 13th, 15th, 16th and 17th) are the best, Charles Hunter deserves credit for the manner in which his greens gracefully tie in with those of his predecessor.

When compiling a list of best first – and nineteenth – holes, Prestwick’s opener surely deserves mention alongside Machrihanish, Pine Valley, Hoylake and Mid-Ocean.

The natural tendency is to shy away from the wall with one’s tee ball but that leaves a crummy view of the green. An American visitor once inquired why they had built the course so close to the airport. The polite member only rolled his eyes.

Third hole, 535 yards, Cardinal; The Cardinal and Hell Bunker at St. Andrews have been in play for over 150 years, forever establishing the merit of placing central hazards directly in front of the golfer. A.W.Tillinghast did it best on par 5s with his famous Sahara hazards featured at Pine Valley, Baltimore Country Club, Baltusrol Lower, Somerset Hills, Bethpage et al. The premise is classic: put your ball in the fairway in order to navigate large central hazards on your second and set up a pitch to a smallish green. In this way, all three shots are tested and each in a different manner. A.W. Tillinghast was smart enough to follow Old Tom Morris’s lead. If only more architects did the same!

The dreaded sleepered Cardinal bunker bisects the fairway 160 yards from the green. Clearing it in two is imperative, which was no small chore for its first fifty years when the gutta percha ball was in use. Even though the much longer rubber core Haskell ball came along at the turn of the twentieth century, the golfer still needs to execute because of Old Tom Morris’s excellent placement of this uncompromising hazard.

Set in a field of humps, the green is an elusive target with depth perception particularly problematic. Give Morris credit for not employing bunkers or better defining the target.

Fourth hole, 415 yards, Bridge; Considered by some to be the first dogleg in golf, the fourth has long held an esteemed position in the game. Macdonald might have considered it a Cape Hole because the same water hazard threatens both the tee ball and approach shot. As with most holes at Prestwick, its full challenge is more nuanced than obvious. To wit, the Pow Burn is there for all to see but it’s the cant of the fairway to the right and the front left to back right tilt of the green that flummox the best decade after decade.

James Braid added this bunker in preparation for the 1908 Open, accentuating the dogleg right nature of the hole. Because of the Pow Burn, the golfer doesn’t sense that he has just transitioned into the calmer portion of the property.

Fifth hole, 230 yards, Himalayas; Though it feels and plays like one of the original twelve holes, the Himalayas didn’t become part of the mix until 1882. Hunter has never received proper credit for the genius of adding a hole that melds so well with the spirit of the originals closer to the clubhouse. When it opened, the Himalayas required a wood to cover the 175 yards with a gutta percha teed on a pinch of sand. Thanks to an expanded set of tees the hole still commands a healthy blow over the 35 foot dune into the unknown. Traditionalists squeal with delight while the narrow minded, thin-waisted professional recoils in horror. ‘This isn’t fair’, he screams! ‘I can’t see what I am supposed to do!’ Yet, long after all the modern courses with their elevated tees and perfect visuals fade from memory, Prestwick stands tall. A well-struck shot at any time on any hole gives the golfer a warm glow of having done well. The Himalayas has the added benefit of providing the golfer with a few minutes between striking the ball and rounding the bend of the hill to discover his fate. The sanguine golfer moves briskly to see if his true strike might be lying stone dead near the hole. That sense of anticipation, that hope, similar to Christmas morning is unmitigated joy. Such moments are sadly absent on conventional one-shotters burdened by perfect optics.

Any links course without a bell is unlikely to be worth its salt. As seen from behind, this hole’s ‘fair’ aspects rarely get mentioned: the putting surface is some fifty yards beyond the base of the hill and is open across the front. If you want unfair, you’ll have to wait until the thirteenth, fifteenth or seventeenth greens!

Thirteenth hole, 460 yards, Sea Headrig; This is the author’s favorite two shot hole in golf. Why? In addition to its outstanding golf qualities, the hand of man is undetectable. When Old Tom Morris brought this hole into being in 1851, heavy equipment was non-existent. Nature’s random, wind-swept landforms of human size and scale are perfectly preserved and presented along the hole’s entire length. Old Tom smoothed over a top of a dune (some say not near enough!) and created one of the world’s most despicably clever green sites. There is not a bunker (i.e. a man-made artifice) within 170 yards of the green because none is required – the landforms as massaged by Old Tom are plenty. After Allan Robertson’s death in 1859, no one better knew what constituted good golf than Old Tom Morris. Unshackled by convention, he created a hole that remains both merciless and infinitely fascinating, attributes that modern architects are seldom able to pair. Thanks to a shared fairway with sixteen, the golfer can play Sea Headrig year after year without losing a ball but at the same time it is also likely to play the most over Old Man Par of any hole on the course.

The thirteenth fairway is shared with the sixteenth. In fact, this golfer is in a bunker made famous by exploits from the sixteenth hole. As his tee ball finished close to the bunker face, the golfer has no choice but to pitch out. He is still left with a third shot of 160 yards into the infamous Sea Headrig green complex.

Sorry Alister MacKenzie, Augusta National and Cypress Point. The author picks Sea Headrig as his favorite thirteenth hole in world golf. The essence of golf has and always will be how the ball reacts along the ground. There is no better example than the thirteenth green complex at Prestwick.

One definition of truculent is ‘aggressively defiant.’ If ever a green complex could be deemed truculent, it is this one.

Fifteenth hole, 355 yards, Narrows; Aptly named, the plunging fairway is the hardest to find on the course. Grass covered hummocks abound and the fairways disappears over a ridge. Even the golfer who is playing well can become unsettled at the prospect of launching a tee ball over such obvious trouble to an unseen, convoluted fairway. Dislodging a golfer from his comfort zone is the object of any good design and Prestwick succeeds at this with flying colors. The approach is nearly as frustrating as the top of the flag is all that is visible on a green that produces numerous three putts.

The twisting narrow fairway is blind from the tee. The tee ball needs to clear the bunker in the foreground and avoid two more farther ahead along the right.

Golfers who think a green should be receptive will have a conniption after they climb the final ridge and gain a view of the fifteenth putting surface. The drop from high left to low right is over four feet.

Sixteenth hole, 290 yards, Cardinal Back; Several great pairs of consecutive short two-shotters exist. The eighth and ninth at Cypress Point and the seventh and eighth at Sand Hills spring to mind. The fifteenth and sixteenth at Prestwick are in the same class and have the benefit of playing wildly different from one another even though they head in the same general direction. While the tee ball is exacting at the fifteenth, the sixteenth fairway rubs against the thirteenth and much more latitude is afforded. Yet, the sixteenth green features the boldest interior contours on the course, including a back bowl that sucks balls to the rear. Two of the most perilous bunkers on the course are found at sixteen where Willie Campbell’s Grave lies fifty-five yards short left of the green and mirrors the backside of the Cardinal front and right. Modern architects struggle mightily to build holes of this length that provide a similar test. Far too often they resort to water as a crutch. The beauty of the fifteenth and sixteenth at Prestwick is that the art of the recovery shot remains intact.

Crumpled links land of the highest order – the sixteenth fairway at Prestwick. This photograph is taken eighty yards from the green and Willie Campbell’s Grave is seen on the left. No guarantees for a level stance are provided for one’s pitch. This is proper links golf after all!

For a hole that measures less than 300 yards, the sixteenth causes an uncommonly great amount of woe. Just ask Willie Campbell who saw his bid for the 1887 Open Championship disintegrate here when he made an eight.

Seventeenth hole, 395 yards, Alps; Often copied, but never bettered, Prestwick’s Alps remains the original and best. It duly impressed C.B. Macdonald who incorporated it as a template hole into his best designs. Indeed, some aficionados of the third at National Golf Links of America consider it to be the finest hole on that course – yet it doesn’t surpass its namesake. Great pressure is put on the player to hit the fairway so that he can then carry the alpine thirty-foot dune. The approach is uncommonly exacting. The great seven feet deep Sahara bunker fronts the green which at only 22 yards deep is the shallowest target on the course. Additionally, the putting surface features a severe roll at its back. The tension created between the deep Sahara and the nasty back to front pitched green puts the screws to the golfer just when the pressure of his match is at its peak. In this regard, it is reminiscent of the penultimate hole at St. Andrews, another Macdonald template.

Does the golfer have what it takes to hoist his approach shot high over the Alps and find the putting surface? That very question has been posed to golfers for over 160 years. The challenge remains as fresh today as when Old Tom devised the hole in 1851. The hollow in front of the Alps is known as the Slough of Despond. It fronted the seventh green on Old Tom Morris’s course, which was to the right.

One of the greatest views in golf is afforded from the top of the Alps. The golfer has no view of the putting surface should his approach land in the massive Sahara bunker. Recovery from behind the green is even more problematic.

The gentle Home Hole might ease the pain from the damage inflicted over Prestwick’s famous final four-hole loop. Upon returning to the clubhouse, and after a sip or two of Kummel, the golfer is bound to think back over Prestwick’s long history. Perhaps a tinge of regret will emerge that the stone wall that ran forty yards in front of the twelfth green is no longer. The club elected to take it down sometime in the 1920s. That’s a pity but because there is so much to cherish, one ultimately finds it hard to imagine that Prestwick, or any other course, could have better withstood the changes to the game from the gutty to the Haskell and from hickory to steel. The course’s mix of quirky features and stout holes provide a perfect blend that asks every imaginable question of the golfer.

Sir Peter Allen has it right in his book Famous Fairways published in 1968 when he wrote, Prestwick ‘… is to me much more than a museum of what golf was like sixty years ago; I find it still a wonderfully subtle and exacting links. True, there are a lot of old-fashioned features, like wooden sleepers in the faces of some of the bunkers, blind shots, and tiny greens with protecting humps and hillocks which may kick your ball away, often unfairly, which can’t appeal to the lordly professionals of today, whose appetite for money, provided by you and me, makes ever-increasing demands that the tailoring of the game and the courses should suit them rather than their patrons, lest they should have to learn to adapt their play to the conditions.’

Space constraints and logistical considerations have obviated any chance that Prestwick will host another Championship. A benefit of that reality is that the course will be spared the tinkering that the Old Course must suffer from time to time. Standing tall and pure, Prestwick remains an anchor for the best that golf has to offer and a beacon for others to understand the origins and principles of the grand old game.

The End

![Cabot Highlands (Castle Stuart) [2016]](https://golfclubatlas.com/wp-content/uploads/2008/12/Castle-Stuart-Golf-Links-500x383.jpg)