Old Town Club, North Carolina, United States of America

Maxwell’s use of the land and his uncluttered architectural style once again set the standard against which clubs in the Southeast and beyond are judged.

Some golf course architects start strong but fizzle. After pouring bright, innovative ideas into their initial work and creating a niche for themselves, they often become handcuffed by new clients who ask them to repeat. Uncommon is the architect whose best work is evenly spread throughout his career. Perry Maxwell from Ardmore, Oklahoma is that rare exception.

Opened in 1939, Maxwell’s The Old Town Club borrowed the best design tenets he had seen over the past three decades. That’s saying something as Maxwell was the man who built such national treasures as Prairie Dunes and Southern Hills, who worked on the best of the best including National Golf Links of America, Pine Valley and Merion, and whom Alister MacKenzie sought for his partner at projects like Crystal Downs.

Indeed, Maxwell got the Old Town project after Clifford Roberts recommended him to Charles Babcock, husband of Mary Reynolds Babcock. The Reynolds family was keen to form a new club as their local Ross course had become crowded. Maxwell drove from Augusta National to meet with Babcock and ultimately went on to build not only Old Town but also the Reynolds Park Golf Course for the city of Winston-Salem. These two courses completed near the onset of World War II essentially brought to a close the Golden Age of golf course design.

In a rare extension of luxury to an architect, Maxwell was offered his pick of 1,000 acres (!) on the Reynolds estate to place the course. One can only imagine how thrilled he was with the 165 acre bloc upon which the course rests today; it had it all. The beautiful topography is highlighted by several high spots that became the first, sixth, eighth and seventeenth tees. Meandering creeks accentuate the low points of the property and helped Maxwell find and build the best sequence of holes.

As seen above, this golfer must flight the ball to the uphill ninth green from an awkward side hill stance. Good players have long appreciated how Old Town’s topography separates the golfer from a range jockey who can only strike a ball well when given a level stance.

In Maxwell, the founders of the club had a man who provided a risk free enterprise. By that, I mean Maxwell was simply incapable of designing an indifferent course – or even hole – at this point in his career. He couldn’t possibly disappoint. The Midwesterner was not the gibbering sort but Sports Editor Nady Cates had this to say July 20th, 1939 in the Winston-Salem Journal: ‘The Old Town links, described by the designer, Perry Maxwell, as one of the seven finest in the nation, is rapidly nearing completion. Already the rolling, tricky course, with its watered fairways and greens, is taking on an appearance of rare beauty and symmetry in a setting unrivalled in this section for its grandeur. At almost any spot on the 18-hole layout one commands a sweeping view of the surrounding scenery….’

What??!! How can that be, you say? While Old Town has always enjoyed a loyal following, its presentation in 2010 engendered no such lofty affection as ‘…one of the seven finest in the nation.’ Obviously, a golf course is a living, breathing thing and courses built during the Golden Age have been around for seven plus decades. Much can change, especially at well-heeled clubs with ready funds. Many more examples exist across the country where clubs were poor – rather than good – stewards. Particular disasters occur when the routing of a Golden Age architect is altered to counteract the advances of agronomy and technology. Less serious, though still offensive, are comprised design features, sometimes done to ease maintenance. Green pads shrink, bunkers lose their character and of course, trees grow, sometimes becoming small forests and big problems.

How does all of this apply to Old Town in a northern suburb of Winston-Salem? Happily, this private club doesn’t seek the limelight and has no need or desire to stage a big event and prove something. Its members are more than content to enjoy the course with friends. This attitude means that the Perry Maxwell routing from 1939 is untouched and that’s good news. How good is it? According to golf architect Bill Coore, ‘Much of Old Town’s brilliance emanates from its routing. I’ve always said that any serious student of golf course architecture must first go to Old Town to see how Mr. Maxwell laid out the course over such an extraordinary piece of property. Given the hole movement and variety, (and the fact it’s still very walkable), that’s quite an accomplishment.’ That’s lofty praise from a man who has routed such gems as Sand Hills and Bandon Trails.

Old Town’s glorious playing attributes provided by Maxwell’s routing never left but some design features faded with time to the point where one couldn’t readily discern that he was playing a Maxwell course. That was the author’s overriding feeling on a rainy autumn day during a 1986 visit. The circular, shallow bunkers bore no resemblance to nature or Maxwell’s Midwestern values. The greens had shrunk, robbing the course of a number of its best hole locations. And of course, tree plantings obliterated the sweeping views and narrowed the scale and grandeur of a bold Maxwell design.

What to do? That was the very question facing Dunlop White, Golf Chairman. An architecture student par excellent, USGA committeeman and past president of the Donald Ross Society, White knew what needed to happen – it’s the same story at most Golden Age designs. Trees need to be removed, playing corridors reestablished, greens pushed back out to their edges and bunkers restored.

The choice of who should do the work was unusually straightforward. It would be Coore & Crenshaw! Bill Coore grew up just thirty minutes south of the course in Thomasville and attended Wake Forest. He was even on their golf team for a season, which gave him access to Old Town on a daily basis for four years. His dorm was within walking distance of the course. Maxwell played an early influence on Ben Crenshaw as well. Like Coore, Crenshaw grew up playing a Maxwell design at Austin Country Club (Riverside) in Texas. This early exposure to Maxwell surely served as part of the foundation for what eventually became Coore & Crenshaw’s shared design philosophy.

How extensive was the work carried out by Coore & Crenshaw in 2013? Maxwell’s bunkers were restored to their approximate original dimensions and shapes and that constitutes ~110,000 square feet of sand and 9 fold increase in the linear footage of bunker edges. Old Town’s bunkers featured 35,000 sq. ft. of sand in 2010 and today their 77 bunkers display 110,000 sq. ft. (their size has more than tripled!). Over 25,000 sq. ft. of putting surface was recaptured. Fairways grew from 35 to a whopping 60 acres and now closely match the scale present in a 1939 aerial. Trees that inhibited an appreciation for the property gave way to open native areas that compliment and add texture to the site’s one-off topography. Along the way, 25 acres of bland Bermuda rough was mercifully removed. Tees were re-aligned to the wide fairways and cart paths removed or rerouted. The list goes on and on so much so that Old Town joins Pinehurst No.2 as Coore & Crenshaw’s most inspired restoration project to date. Rarely does a course experience such a remarkable improvement.

Gorgeous, sweeping long views are now afforded throughout the course’s interior. Above is the red outbound flag at the seventh with the massive bunker and yellow flag at the inward twelfth several hundred yards away.

Apart from the thinning of trees, most of the work was completed in a 10 month window. Dave Axland and Keith Rhebb did a fantastic job with the bunkers. Coore concentrated on the greens, and Quinn Thompson closed the deal with his detail work and nativeplantings. Accolades have greeted the restoration, pleasing no one more than Dunlop White whose research and behind the scenes club work paved the way for this exemplary outcome.

There was never any question that Coore would accept the project; he has long hailed Maxwell as one of his very favorites and acknowledged how influential Old Town was for his career. He has noted on many occasions, “Old Town and Pinehurst No. 2 served as the cornerstones for my early understanding of what extraordinary golf course architecture was all about.” Notoriously finicky about projects that hold interest, this would be a labor of love for Coore and it shows in the completed work as demonstrated below.

Holes to Note

(Please note: Two yardages are given, one from 7030 yards that the golf team at Wake Forest uses and another from 6280 which makes for a very charming course. Par is a tight 70.)

First hole, 425/395 yards; An opening hole should set the stage for what the golfer can expect the rest of the day and Old Town’s does that to the nth degree. A wide, tumbling fairway greets the golfer with flatter sections available to the better golfer seeking an advantage. Regardless, the golfer is likely to have to make fiddly little adjustments to accommodate the uneven stances dished up by the sloping fairway. Atop a rise, a superlative green awaits and like many greens here, one that even good players can putt off.

An inordinate amount of time was spent by Coore & Crenshaw perfecting the short right bunker. As it serves as the introduction to the course, Coore was insistent that its scale and presence command attention. Also worth noting is the appropriately colored sand which originates in the not too distant Yadkin River. Ultra-white sand would not have suited the property.

Second hole, 165/145 yards; Maxwell’s first course Dornick Hills and masterpiece, Prairie Dunes also feature one shot second holes. Throwing in a one shotter early was clearly something he enjoyed. As at Hutchison, Kansas, this one features a green that is wider than deep and places a premium on keeping the ball below the hole.

Yikes – here is a 2010 photograph of the second hole which bears little resemblance to a Maxwell creation.

Here is the 2014 version. Note how much better the bunkers are integrated with the green. Throughout the course, Coore & Crenshaw recovered two to three feet of bunker depth, providing the necessary three dimensional qualities that all great bunkers possess.

Look at the day’s tricky back right hole location just over the rise. Less difficult is the walk to the next tee as it’s just behind/on top of the back bunkers.

Third hole, 430/370 yards; This early hole returns the golfer to the clubhouse, something Maxwell had seen done at Pine Valley. In fact, plenty of members get their golf fix by playing only this three hole loop. Between Maxwell and Coore, the features that lend this hole its playing qualities are where they belong: down the middle! A well crafted high right bunker interacts perfectly with a new one cut into a central mound 130 yards short of the green. Slotting one’s tee ball between these two is just the start as the green features what the members refer to as a ‘muffin’ near the middle of the putting surface. Such a Maxwell creation – a gentle rise or puff in a putting surface – provides many interesting hole locations, all in the most uncontrived manner possible. Pity more architects don’t follow Maxwell’s lead.

Some of Coore & Crenshaw’s most interesting – and varied – bunkers are found at Old Town. Note the attractive hard edges.

With width restored, Coore had the option to install central bunkers where needed. This one cut into a mound at the third has caused Webb Simpson to revise how he plays the hole from the tee.

Fourth hole, 525/515 yards; This is one of the best holes on the course to get off a good drive. Once over the brow of the hill, a well struck tee ball bounds happily along and makes the hole reachable – and it’s a thrilling shot because the approach is even more downhill than it is at Augusta National’s fifteenth. Similarly, both greens are pushed up from their surrounds but there’s a greater range of trouble here in the form of a jungle right and long, a creek 40 yards shy of the green and gnarly hay left. Most golfers have learned to bump it down the hill and be content with a level stance for a 100 yard pitch.

The easiest hole on the course has plenty of defenses for those who employ aggressive tactics. Nonetheless, the back to front tilt of the green can accommodate a long iron approach.

Fifth hole, 410/365 yards; Maxwell still enjoys a very devoted following to this day. It helps that three of his very best works, Prairie Dunes, Southern Hills and Crystal Downs are all very well presented. A true fan will step onto the fifth tee and immediately recall the fifth at Crystal Downs. Both holes are sharp doglegs left with deep bunkers cut into landforms on the inside of the dogleg. The hole at Crystal Downs is a bit shorter and as such, provides a greater range of outcomes but both are impressive drive and short iron holes.

Just carrying these bunkers on the inside of the dogleg is important as this sneak peek under the specimen oaks shows an eight foot deep greenside bunker that complicates approaches played from the right.

By 2000, the fifth green had morphed from subtle rolls to distinct tiers, a most un-Maxwell feature. Dave Axland worked and worked – and worked – to restore Maxwell’s puffs on the putting surface with great success, as seen above in this view from the right side.

Sixth hole, 190/175 yards; When you stand on this tee, you’d like to have your affairs in order as the going gets noticeably tougher for the rest of the round. One of the neat tricks about Old Town is that it oozes charm even when its challenge is severe. Old Town’s ultimate trump card is that it’s both great fun (ask the members) and a great test (ask the Wake Forest golf team alums). Epitomizing this is the sixth, whose green extends the fairway as a tongue of land that falls away sharply left, right and behind. While a lot of Old Town’s putting surfaces are on high spots and/or fronted by a creek, this putting surface (the largest one on the course at 6,600 square feet) enables a run on shot and plays an important role in rounding out the variety of shots required to play the course well.

Though the high tee in the corner of the property is sheltered, the sixth green is not and the putting surface bleeds away on all sides. Plenty of tee balls find the putting surface – briefly.

This newly created Coore bunker is actually forty-three yards shy of the putting surface and creates a blind area from the tee. While optically challenging, the golfer who judges the distance properly sees his tee ball tumble onto the open green.

Seventh hole, 445/345 yards; Maxwell’s time with Alister Mackenzie at Crystal Downs again seems to rear its head. On this long, uphill hole the golfer might reasonably expect an ample target for his second shot but like the cruel thirteenth green at Crystal Downs, he encounters one of the smallest, most tilted putting surfaces on the course. It’s a mere 3,240 square feet. According to White, ‘Variations of undulation and contour are at the heart and soul of this course. It’s the distinguishing bedrock of both our fairways and greens. They deserved stature and presence, so we literally unveiled these distinctive features that had long been plugged-up by trees and obscured by their long morning and afternoon shadows. We brought them to life! Undulations and contours are helpless if the golf ball does not react to them. In turn, sun and air movement helped dry out the turf, and an aggressive topdressing program firmed up our playing surfaces. Today, Mr. Maxwell’s undulations and contours once again have visual and physical relevance.’ Well said (!) and the seventh is a superb example.

Short grass and width provide options but the hole still demands exact ball striking. The ideal progression is up the high left side of the fairway where the good golfer carries the bunkers long left to shorten the approach. Balls hit center or right of center are shunted further right by the terrain, progressively worsening the approach angle.

Before the restoration, this was the cramped view from the seventh tee and the land was robbed of playing such a significant role.

Golden Age architects excelled at cutting bunkers into natural upslopes. So do Coore & Crenshaw! This zoomed view also shows how much more accessible the green is from the left than the right.

Eighth hole, 415/380 yards; The word ‘links’ is so ill-advisedly used these days that it has lost meaning. There are links in Las Vegas for goodness sakes! Nonetheless, it is quite interesting to note that Perry Maxwell himself (a humble family man with no marketing ability) referred to Old Town as a links. For sure, its land and the way that he incorporated the landforms provide a number of links-like situations where you land your ball at Point A to end up near Point B and there are several drives like the one at the eighth where you don’t see the ball finish.

Lanny Wadkins offered one of the great lines of all time. When asked how often he used the library at Wake Forest, he responded with words to the effect that he used it every single day — to draw his drive off its steeple on the eighth hole at Old Town!

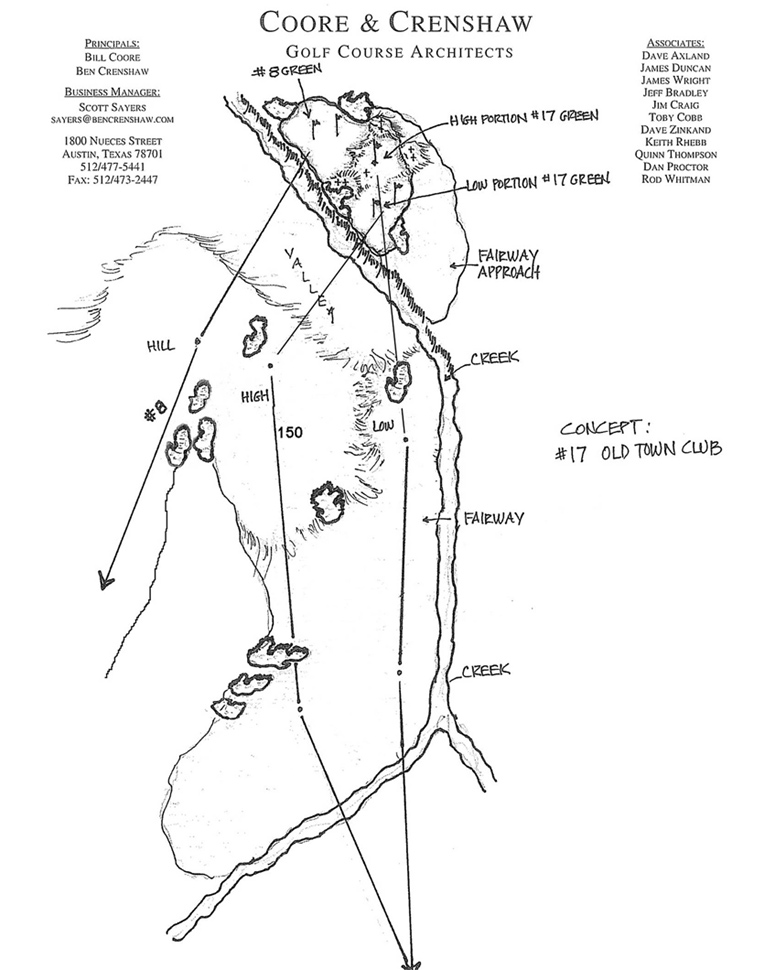

Speaking of links, Maxwell’s 1919 visit to Scotland played an enormous role in shaping his views of what constituted good golf. St. Andrews and its rippling contours were natural favorites. Initially, Maxwell had the eighth and seventeenth greens close but not touching. It was Clifford Roberts who chided him for not building a Double Green in view of his appreciation for St. Andrews. Maxwell responded with the one and only Double Green of his career. Not surprisingly, it had shrunk dramatically over time so that Coore’s restoration more than doubled its area to a whopping 16,700 square feet. Numerous interesting hole locations abound.

Tenth hole, 410/400 yards; Another example of how routing matters, Maxwell draped the fairway over the land that disappears over the brow of a hill. If you look at the tree lines left and right you’ll see that Maxwell didn’t disturb the land one iota. A modern architect armed with heavy dozers might have altered the crests of the hills to ‘improve’ sight lines. If so, this hole, 4, 8, 12 and 13 would have been shamefully robbed of their inherent charms. Maxwell’s innate appreciation of the land is demonstrated again at the green where the putting surface follows the high left to low right inclination of the surrounds.

At 3,160 square feet, the tenth green is technically the smallest target on the course. Yet, it’s a nifty approach with the golfer given several ways to work a ball close to the hole location – including letting the land do the work for him.

Eleventh hole, 220/180 yards; Some folks constantly yearn for the ‘good ol’days’ – in fact the good old days at Old Town are now. Coore & Crenshaw’s work combined with O’Neil Crouch’s superior greenskeeping practices make Old Town the best it has ever been. Take this hole where Maxwell beautifully and seamlessly let the fairway feed directly into the putting surface. All skill sets can enjoy it. However, several decades ago, a berm was added above the creek bank to keep water from overflowing. As a result, the ground in front of the green on this long par three was usually soft and spongy. The green could only be approached through the air. Enter Dave Axland, who cored out the approach, brought in a sandy topsoil mix and massaged the grade of the ground so that the entire area in front of the green plays fast and firm. Now, Maxwell’s full vision for this hole is revealed.

Though the eleventh lays peacefully upon the ground, a lot of work was required to ensure that it plays as well as it looks.

Twelfth hole, 455/415 yards; Old Town’s stature within the state of North Carolina and within Maxwell’s portfolio is elevated by three superlative holes on the back that share a common design trait. The holes are here, fourteen and seventeen and though straight, they are multi-optional. Here, some golfers beat a ball along the high left side as it provides for a one club shorter approach. The rub? The approach is blind. Other golfers aim for the middle and allow the tilt of the fairway to drift their tee ball into the lower, flatter quadrant of the fairway. From there, a good amount of the putting surface and the flag is visible even as the sideway roll has robbed the tee ball of forward distance. Each and every day the golfer is greeted with the same wonderful question: How shall I tackle this hole today? Such a pleasant conundrum keeps the course fresh round after round, year after year, generation after generation.

Most inland courses lack topographic interest found among the random landforms so plentiful on links courses. Not so here as the distant directional pole suggests. Links lovers will be reminded of Rye or Brancaster.

The largest bunker on the course occupies the hillside left of the green. Its presence is felt throughout much of one’s round and it took Coore & Crenshaw nearly three months to complete. One could be forgiven for thinking that we are in Maxwell’s beloved Midwest.

Fourteenth hole, 340/315 yards; This is the gorgeous little sister with whom everyone falls in love. Maxwell perfectly benched a sliver of a green into the hillside, creating a teaser where generations of golfers have struggled. A skilled fade off the tee allows the golfer to look down the length of the green and approach from green level. Much more fairway exists left but that relegates the player to the lower ground and a disadvantaged angle. This drive and pitch with timeless qualities ranks as Maxwell’s best sub-350 yarder that the author has seen.

From the right side, this pleasant view encourages bold thoughts of a pitch and putt birdie. Take note of the rear bunkers however. Coore and Axland wanted the golfer to see ‘alligator eyes’ emerging from behind the green. Voila!

From the left, the golfer needs to make sure his ball reaches well onto the putting surface as otherwise…

Fifteenth hole, 250/190 yards; Most people prefer downhill par threes. To say that a weakness of the course is that the first three par threes all play downhill is to sound like a grumpy old man. True, the author likes uphill par threes and so did Maxwell based on holes like the tenth at Prairie Dunes and the eighth at Southern Hills. There are none like that at Old Town but to compensate Maxwell created this very long one shotter where he exploited the creek on the left to great effect.

Also, it is worth noting that each par 3 at Old Town faces a different direction, and each builds in distance.

Golden Age architects were the masters of the give and take. After the short fourteenth, Maxwell comes back hard at the golfer with this daunting one shotter. A draw is a handy shot to possess as it can find Maxwell’s opening on the right and bounce well into the green.

Sixteenth hole, 365/360 yards; Maxwell’s imaginative routing ‘discovered’ this distinctive hole. When faced with the abrupt shoulder of a hill, what did he do? He placed the fairway on the highest ground, requiring the golfer to climb this massive landform. Thankfully, the hole’s length makes it manageable and the approach to the perched green is quite attractive. Befitting this length hole, the green has two distinctive Maxwell rolls that place a premium on finding the proper portion given that day’s hole location.

The view from the sixteenth can be disconcerting. The restored short bunker isn’t in play but it breaks up the view nicely.

With natural green sites like this, Maxwell didn’t have to create extraneous features for the hole to become an enduring challenge.

Seventeenth hole, 630/555 yards; Some of the author’s favorite par fives in the world – the sixth at Pebble Beach, the eighteenth at Yale, the second and thirteenth at Cabot Links – possess a ridge that must be scaled with the second shot. Do so, and a birdie may be at hand. Fail and the odds of even par are stacked against you. This hole joins that distinguished list.

This long view taken in the fall by Dunlop White shows the large bunker complex left that must be avoided off the tee and the central hazard ahead that one must pass with the second.

Eighteenth hole, 445/370 yards; Silas Creek along the seventeenth is the lowest point of the second nine and the uphill Home hole returns the golfer to the well positioned clubhouse high on the hill. The drive is into the crest of the hill but the ascent is more gradual and less daunting than at the ninth. Only the longest, best placed tee balls will afford the golfer a view of the putting surface. Most of us just see the top of the flag fluttering which is problematic as Maxwell saves some of his finest interior contours for the Home green.

The ninth and eighteenth holes share a common teeing ground. Rather than clutter up the area with a bunch of closely placed tee markers, the inspired decision was to use only one set and have them broadly placed. It works wonderfully well at a private club like Old Town where the number of full rounds is less than 15,000 per year.

Note the distinctive double greenside bunkering at the right front of the eighteenth green. The golfer’s ball is at the apogee of its arc and dropped softly beside the hole.

Though golf courses come in all shapes and sizes, their ultimate quality is dependent on the adherence to a few basic tenets. One is routing: how well does the architect incorporate the site’s features into the playing characteristics of the holes? The more abundant the natural features, the more distinctive the course will be if smartly employed by the architect. Another primary factor is the design details, namely the placement and construction of hazards as well as the variety found in the green complexes. Added to these two cornerstones of design are such things as general setting/surrounds and the variety of shots required. The evaluation of these variables is a good way to gauge a golf course.

The thing about Old Town is that it now scores uniformly high across the board in all meaningful categories. The course and its presentation have little weakness but in what amounts to a methodical and relentless march toward perfection additional refinements are on-going under the watchful eye of Dunlop White and Coore & Crenshaw. New vistas are being exposed across the interior of the property, fairways refined and more Bermuda rough eradicated.

The results are dramatic and the result of a thoughtful, measured process. The club properly placed its faith in a dedicated and knowledgeable golf chairman who hired the right people. After countless site visits and armed with historical data Coore & Crenshaw created a strategy and process to restore the features of Maxwell’s original bold ideas. The extraordinary results here and elsewhere are the product of a well-constructed vision shared by a respected club leader + the right architect + an engaged greenskeeper. This is the template for the most successful transformations that this country has seen, including here at Old Town, California Golf Club of San Francisco, Sleepy Hollow, Los Angeles Country Club and St George’s on Long Island. No miracles occurred at any of these places: just good, smart work and it’s a pity so many other clubs move in small, half measures.

Coore, in his usual way, strikes a deferential tone when speaking of his hero, Maxwell. He says ‘I can only hope we did work that Maxwell would be proud of.’ I’ll tell you this – there can be no doubt.

The End

![The Park, West Palm (Lit 9) [2023]](https://golfclubatlas.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/IMG_7092-2-scaled-500x383.jpg)