Los Angeles Country Club (North Course)

California, United States of America

A new dawn has come to Los Angeles Country Club. Its regal North Course designed by George Thomas and Billy Bell has been immaculately restored and the club now prepares to host the biggest events in amateur and professional golf.

Golf originated by the North Sea on links land. As it gained in popularity, the game moved inland, first to the unique heathland belt around greater London and later to parkland settings. In the United States of America, parkland courses out-number all other forms of golf combined, including ocean, mountain, desert, and prairie courses. What’s surprising is that perhaps the single finest example of parkland golf isn’t found in a bucolic setting on the outskirts of a major city but near the bustling intersection of Wilshire and Beverly Hills in California. The vibrant setting for the North Course at Los Angeles Country Club is akin to a golf course in Manhattan’s Central Park: distant skyscrapers heighten the golfer’s appreciation of the tranquil beauty around him and the deer and the foxes (!).

Of course, back when George Thomas went to work on the North Course, it was in the country. Times have changed (!) but Thomas’s design values endure. To the author, what Thomas accomplished between 1925 and 1928 constitutes the greatest burst by an architect in the history of the game. During that brief span, and joined by his design associate Billy Bell, Thomas created Bel-Air, Riviera, penned the cornerstone Golf Architecture in America and then oversaw the complete rebuild of the North Course. Superlatives fail to do the man justice.

Born and raised on the east coast, George Thomas was influenced by the Philadelphia School of Design and especially its two design monuments, Pine Valley and Merion. By the time Thomas moved to Los Angeles in 1919, he had built several courses back east. In 1921, the Los Angeles Country Club sought to upgrade its two courses that had been laid out by several members including Ed Tufts and Norm Macbeth. At the time, the Englishman Herbert Fowler enjoyed one of the biggest names in the profession, having built several pre-eminent courses in England prior to World War I including Walton Heath and the complete revision of Westward Ho!. After World War I, his design services were in demand in America and his figure 8 routing and resulting holes at Eastward Ho! on Cape Cod showed great imagination.

He ventured west to Los Angeles by train. For reasons unclear, the 36 holes that Fowler laid out for LACC in the early 1920s weren’t of the same caliber as his top tier designs. Thomas even oversaw the construction of the North Course on behalf of Fowler, who returned to England prior to the North Course opening. As much as any man, Thomas knew of its deficiencies. In 1926, LACC agreed to host the inaugural Los Angeles Open. Harry Cooper, an accomplished champion, won with a score of seven under par but the powers that be deemed the course insufficient. The author can only surmise that it must have centered around a lack of strategy and Fowler’s predeliction for straight holes – and Thomas would have been relentless in pointing that out.

By that time, Thomas had completed Bel-Air (originally a phenomenal work of architecture running through canyons) and was finishing Riviera. Thomas had both the reputation and ability to convince the club to let him have a go at modernizing the North Course. Compared to Fowler, Thomas emphasized playing angles. His quote that ‘Strategy is the soul of the game’ says it all. Off Thomas went! Only two holes (the first and eighteenth) ended up occupying the identical ground as Fowler’s holes once Thomas was done. As a side note, Thomas let Fowler’s infamous seventeenth, a tiny 110 yarder played to a wicked sub-2000 square foot green, go fallow without altering its one-of-a-kind perched green pad. To the delight of all, Hanse Design brought back this hole as an alternate hole during their 2010 restoration.

Thomas had a love/hate relationship with Little 17. He went to comically painful lengths in his book to explain that he didn’t mess up with a left hole location during a big event, writing, ‘I never admired Macdonald Smith so much as when he proved to that crowd of golfers that the uncommon and tricky conditions existing could be met by the man who played with his head as well as his hands.’

As Thomas was an eloquent writer, we know the importance he placed on topography. Thomas could have well been describing LA North when he wrote in 1926:

To my mind, the most important thing in the Championship course is the terrain, because no matter how skillfully one may lay out the holes and diversify them, nevertheless one must get the thrill of nature. She must be big in her mouldings for us to secure the complete exhilaration and joy of golf. The made course cannot compete with the natural one; that is why we so often hear how superior the dunes of linksland are to inland courses, because inland courses are, many times, uninteresting and flat; but on the other hand, there are many inland courses which are as fine as the linksland by the sea.

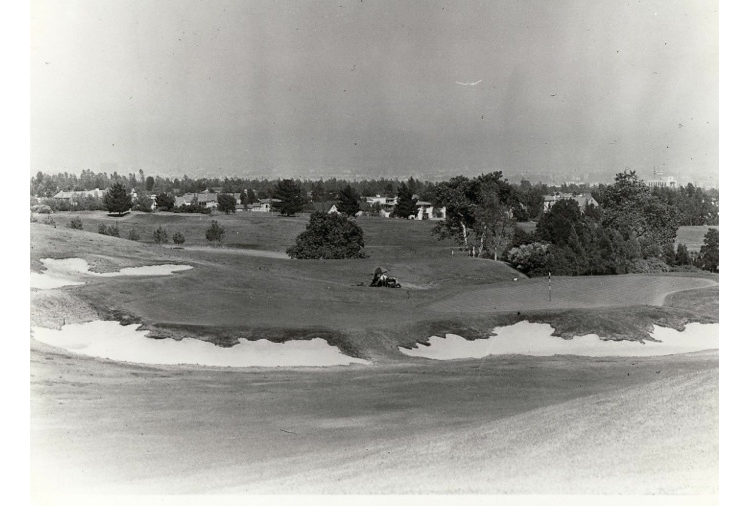

Of their Big Three designs around Los Angeles, the North Course occupied the best raw property for golf. Indeed, its diverse nature makes it one of the finest parkland sites imaginable and George Thomas’s 1927 re-routing took superb advantage of the numerous hilltops, valleys replete with washes, and ridges to create a series of distinctive holes that seem unique in world golf. As Gil Hanse puts it, ‘the course enjoys a perfect sense of place and balance.’

Coupled with Bell building the design features so well into the ground, they built a course that should have stood the test of time. Alas, Thomas passed away in 1932 during the Great Depression. Pearl Harbor and World War II followed and decades passed during which golf floundered. Even a club like Los Angeles Country Club isn’t immune to passing fades and fancies. By the 1990s, the course was plush and manicured. Verdant grass was a priority and the gnarly, sandy wash that was once a dominant feature of the front nine had been sterilized. Sensing the course had strayed from its Thomas roots coupled with a desire to save on water, the club pursued native areas in 2005. The unintended consequences were lost balls and grumpy members.

Having returned to LACC in 2003, General Manager Kirk Reese had a fresh set of eyes and appreciated that some form of action was required. He instigated restoration dialogue with the green committee and board. At the suggestion of local architect and author Geoff Shackelford whose books on Thomas including The Captain have long celebrated what made Thomas special even among other Golden Age titans, the club decided to call in Hanse Design. A series of eloquent presentations to the club by Hanse detailed what a special course they once had. Green Committee Chairman Don Rice worked with past Club Presidents Barclay Perry and Bob Cooper to steer the club in the best direction possible by making the scope of the project grander, not smaller. The end result would not have been so comprehensive if not for their help in pushing for detail items like bringing back Little 17 or tying the tenth fairway into the sixteenth fairway. Eventually, the club green-lighted work to commence, despite the unstable American economy.

Phase one restored the fairways bunkers, including those short of the one shot eleventh hole and was completed in 2009 to unfettered acclaim. LACC quickly proceeded with greenside bunker restoration, new tees, re-grassing, irrigation, the removal of shrubs/trees and re-establishing the wash. Such work was completed in October, 2010. Hanse thinks that ‘The two stage process of doing the fairways bunkers first followed by the rest gave the club leadership the confidence that we were on the right track. The membership buy-in was crucial as it eventually allowed us to get the second and eighth greens returned to Thomas’s positions.’ New Greenkeeper Russ Myers was integral to the overall success of the restoration and continues to refine and perfect the presentation of the course. Hanse expresses it more succinctly: ‘Overstating Russ Myers’s importance to the entire project is impossible.’

The removal of vegetation opened vistas so that all golfers now freshly appreciate the scintillating property with which Thomas and Bell had to work.

The bunker restoration process worked as follows: Gil Hanse, Jim Wagner and Geoff Shackelford staked out the old bunker areas, which were generally larger than what had evolved. Hanse would get on the dozer to find the lost bunker or shave down years of build-up. Wagner did the detail work creating the new form and then Shackelford worked with Hawk Shaw Construction in stacking the sod to give the bunker faces an evolved appearance that mimicked Bell’s work. This is an old course and the restoration would feel like a failure if the bunkers appeared ‘new.’ So successful was the project, that the bunkering (placement and aesthetics) and use of hazards here rivals those at the best parkland courses in the country including Oakmont and Merion.

Bunkering at the wide but shallow twelfth green is an example of the work that was accomplished, creating a natural, rugged quality appreciated …

… in this close-up. Hard to imagine that the bunkers are less than five years old in the photograph above!

Central to the success of any restoration are: How well thoughtout and complete was the scope of the project? How good was the in-the-dirt work? How much were the worst holes/features improved? By all measures, the restoration of the North Course at Los Angeles Country Club ranks at the top with the very best, including Gil Hanse’s own transformational work at The Country Club, Sleepy Hollow, Quaker Ridge, and the East Course at Winged Foot.

Holes to Note

(Please note: the Long Tees on the North Course measure over 7,200 yards and provide as strict an examination as any parkland course in the country. Indeed, the North Course may well be the hardest course in the state on a calm day. Both it and the Bell tees of ~6,600 yards are referenced below.)

First hole, 580/545 yards; Thomas groused, ‘We hear complaints of anything and everything that keeps poorly executed shots, which were played without proper thought, from reaching a situation as advantageous as that secured by another man who has carefully planned and placed his ball.’ Clearly, the man had little time for people who displayed a sloppy approach to the game. More than any architect alive or dead, Thomas’s work required the golfer to think and continually weigh options shot after shot. As a result, the author puts George Thomas among the handful of all-time greatest architects, so the fact that LACC once started and ended on such weak notes never made sense. Of course, the answer lies in how the first and Home holes had evolved. Once grand in scale, the two holes had become artificially separated by rough and a row of spindly trees. Today, the golfer stands on the first tee and sees an ocean of short grass shared between the two fairways as he prepares to tee off under the watchful gaze from members in clubhouse directly behind. Reminiscent of the Old Course at St. Andrews, the connected fairways extend 135 yards (!) in width. Instead of a burn and Valley of Sin, sprawling bunkers and angled greens lend the two holes here their strategic interest.

Note how the green bleeds away back left, forcing golfers to try to get past in two the right front bunker that is eighty yards short of the green.

Second hole, 490/440 yards; At the heart of any restoration is returning the holes to their original form, though allowances such as additional tees and fairway bunkers can be made to counteract changes in technology. In 2005, the front nine suffered mightily from three greens that were not in Thomas locations, namely the second, sixth and eighth. All three were put back by Hanse Design which helps the North Course now lay claim to being the most pure example of Thomas’s work. The second had been turned into a par five by moving the green right nearly 100 yards and uphill from its original spot on the far side of a barranca. As seen also at Riviera, Thomas thought an easy par, hard par was the ideal start to a round. As these back-to-back par fives played in 2005, most players had a wedge into the first and a wedge into the second. Thomas courses always featured more ebb and flow between holes, which is part of their enduring charm. A lack of monotony is a chief aspect to keeping a courses ‘fresh’ in players’ minds with the North Course being a prime example of Robert Hunter’s dictum that a course should not ‘have holes of similar character follow each other.’ That core principal was violated when the second green was moved. Nonetheless, the club board faced a tough decision in restoring its location because the eighth green had been pushed back thirty yards and occupied roughly where the old second green had been. Committed to Thomas’s legacy, the board ultimately gave Hanse Design the go ahead to restore both green sites. A contentious issue, time has shown it was the proper decision. The give and take of not only the first two but the first eight holes was markedly improved and a slew of 1/2 par holes now greet the golfer.

If the golfer doesn’t get away a cracker of a drive, then his thoughts surely should turn to how and where to lay up on this par 4 1/2.

The newly restored second green once again occupies its rightful space inside the elbow of the wash. Same too for the eighth green which is once again 40 yards behind the second green, just as it was in Thomas’s day.

Third hole, 400/400 yards; Though many modern architects might flatten the landing area, Thomas and Bell did not as they treated natural fairway contours as integral with the hole’s strategy. In this case, the golfer may elect to forgo distance off the tee in order to gain a flatter stance for his approach. If so, he is left with a mid-iron approach to a green strikingly bunkered front center. Given the visual intimidation of this Bell bunker, many golfers are long with their approach, which provides its own challenge as the green races away from back left. According to Shackleford, ‘Recapturing the green sizes, and thereby some of the best hole locations, was one of the biggest components to getting the character of the course back. Thomas’s green contours were never more than just extensions of the land, however he did love to create all sorts of wings and and caverns to have the option to set courses up in interesting ways. Obviously, the entire third green, which is kind of a starfish now with holes in front and back left/right took that green from being a circle to having the potential for radical day-to-day variety.’

This view highlights the hole’s rolling topography and how each golfer above faces a decidedly different angle/approach.

As seen from the high left side, the third green is the largest putting surface on the course at nearly 9,800 square feet and is shaped like a tooth with Bell’s famous fronting bunker eating into the front middle.

Looking back down the third fairway, the juxtaposition of man and nature is nowhere more acutely felt than Los Angeles Country Club.

Fourth hole, 210/200 yards; Thomas wrote, ‘One shotters are most important. In these holes one gets a keener interest on the tee shot than the others, because it may be played to the green by most men. To my mind, five one shotters are not too many.’ And so there are five one shotters at LACC, where a full gamut of shots from downhill to uphill, from a short iron to wood are required. This one kicks off the quintet and to appreciate how the aesthetics have changed in the past five years, look no further than the before and after photographs below.

Thomas placed this hole here for a reason, namely to take advantage of the wash. Today’s green complex looks like it organically rises out of its surrounds as compared to …

… this version from 2005. While the shot/goal remains similar, the ‘before’ hole is indistinguishable from countless downhill par 3s around the country while the ‘after’ hole properly reflects the hole’s distinctive natural environs.

Over a playing season the golfer once again encounters a wide range of recovery shots on the handsome fourth.

Sixth hole, 335/320 yards; Before the restoration, this was a simple drive and pitch hole as meaningful options didn’t exist. Plop the ball down the hill, wedge on and go from there. Straightforward stuff with a lot of pars and some birdies. After the restoration, a myriad of decisions confront the golfer. As a result, this hole has again become the multi-dimensional gem that Thomas installed and produces a range of scores. Give Hawk Shaw credit here too for being such careful shapers as they first picked up on the change in sand at the green site. Sure enough, the Thomas green pad was a good 10 feet lower than the present one and Hanse Design quickly set about returning it to its initial elevation. Hanse notes that ‘… by slowly peeling away the layers, we could trace the contours of the both the old second and sixth greens, which was a first for me. It was a very neat process, one that we enjoyed immensely.’

… some members have concluded that the best play is to go long off the tee, past the hole, and then pitch back toward it as seen above.

As seen from behind, 40 yards of fairway extend from the green on a direct line back toward the tee. Dare the tiger try and make the carry? Under 4,000 square foot, the sixth green represents the smallest target on the course.

Seventh hole, 290/235 yards; Thomas opined that ‘…the truly Ideal course must have natural hazards on a large scale for superlative golf. The puny strivings of the architect do not quench our thirst for the ultimate, and as part of such topography we must include sufficient area.’ The last component of that quote centers around sufficient space and the sensible tree/shrub management program that LACC embarked upon in 2010 has had the effect to highlight LACC’s extraordinary terrain. Here at the seventh, we find ourselves secluded in a lovely valley at the low point of the property which embodies the first part of the quote and the need for natural hazards. Great design boils down to the skill of the architect to incorporate a property’s attributes into the final design, hole after hole … after hole. While a wash with its eroded walls and native vegetation makes for a fine hazard, it becomes especially fine if it runs diagonally across the hole (think thirteen at Augusta National). Thomas did just that at the seventh.

As seen from behind, the thirty yards of fairway on the side of the green becomes evident. A 290 tee from above the sixth green exists that makes this patch of fairway quite a consideration. Thomas’s concept of ‘a course within a course’ comes to fruition when the back tee is coupled with the back right hole location as the only way to access it is from the fairway short of the green.

Eighth hole, 535/535 yards; This is the third 1/2 par hole in a row, a true design rarity/accomplishment. The tiger dearly wants to strangle a ‘4’ out of this double dog-leg as the green was moved forward 30 yards to its original Thomas location but doing so is another matter altogether. The rub is the left to right sloping fairway which frequently dictates that the second shot be played with the ball below the player’s feet, just when he would like to draw the ball – a difficult task. Those in attendance at the North Course re-opening in the fall, 2010 still marvel at the low draw Fred Couples played from the hanging fairway lie to reach the green in two. Alas, most of us have to be content with a pitch to this right to left sloping green. Few clubs have the courage to shorten a hole as part of a restoration; give LACC full props for doing so.

Considering the course’s location amid a teeming urbanscape, there are a surprisingly number of quiet moments during one’s round. Crossing the bridge over the wash at the eighth is among them.

The Thomas mounds and Hanse bunkers left and the hillside on the right place an appropriate premium on accuracy at this 4 1/2 par.

As seen from behind, the eighth is a superlative switch back hole which requires a fade off the tee and a draw for one’s second. Thomas left the green open in front to reward those with the uncommon ability to execute the tandem plays.

Ninth hole, 180/180 yards; Golf is played across the barranca on six of the first nine holes. Half of those times occur at the one shot holes whereby Thomas affords all golfers a perfect stance/lie on the tee from which to make the forced carry. More importantly, note the variety in how Thomas incorporated the wash. At the downhill fourth, it is a fronting hazard. At the level seventh, the wash is set on a diagonal. And here at the uphill ninth, the gulley is well short of play, bothering only the duffed tee ball. Talk about text book – and it didn’t happen by luck. In 2005, this oval-shaped green afforded a simple row of middle hole locations. Hanse Design recaptured nearly 25% of putting surface and returned the green to its original dimension of 6,635 square feet, primarily by expanding the green at the front, back left and along the right. A minimum of four great locations were recovered in the process with back left hole locations requiring as much as four more clubs than the front one seen below.

This view from behind hints at the 44 yard depth of the newly restored green as well as how much lower the tee is. Indeed, the ninth generally plays a full club more than the first timer imagines. This front hole location is sneakily fiendish (and didn’t exist in 2005), as most golfers are left with a dastardly quick putt from above the hole.

Tenth hole, 410/385 yards; Not every hole can be a strategic marvel but every hole can/should be interesting to play and this one scores well in that regard. The landing area is a huge knob into which Bell carved two wonderful bunkers. From anywhere near them, the golfer is more or less level with the putting surface and is afforded a comforting view for his approach. The shorter, more direct line left off the tee and away from the bunkers leaves the golfer in a valley below the green with a stunted view of what he needs to accomplish. How best to play the hole? Each golfer must make up his own mind – and that makes the tenth interesting.

Thomas draped the holes across the land in every imaginable manner possible. Flat courses can’t begin to compete.

Eleventh hole, 275/225 yards; The architectural merits of this famous hole equal the one-of-a-kind view and it’s a mystery where Thomas/Bell gathered all the fill to create this mammoth push-up green, which is elevated nearly twenty-five feet at the rear from its surrounds. Bell’s graceful tie-in of the massive green pad with the hillside on the left is nothing short of stellar. Watching the drama unfold on this Reverse Redan is great sport. Considering its length, many golfers still play it as Thomas intended by hitting the ball short left and having it bounce onto the putting surface. Figuring out how to access the front hole locations will drive the amateurs crazy during the 2017 Walker Cup and the professionals bonkers during the 2023 U.S. Open. So too the putting – is the putt downhill or uphill?

A large cache of aerial shots helped Hanse Design. This is one of the rare pre-1930 ground photos that they found and it served as a template for the Billy Bunker style they emulated.

As seen in 2005, the bunkers had become sculpted and manufactured in appearance. Something needed to be done.

The first phase of work was completed in 2009 and returned the bunkers to a form that would make Thomas and Bell proud.

The second and final phase saw to the removal of shrubs, undergrowth and some trees. For the first time in decades, members and their guests could appreciate both the special property and the special architecture.

Thirteenth hole, 470/430 yards; The rolls in the land here are of the sort not found on other parkland gems like Winged Foot West and Riviera and made the perfect canvas for Bell’s stylish bunkers to both dictate play and enhance the beauty of the surrounds (this statement is not made lightly as the Playboy Mansion is past the thick hedge behind the green!). MacKenzie, Tillinghast and Thomas are unmatched at creating long two shotters that are a delight to play. At the thirteenth, the golfer should carry his tee ball as high and as long left as possible because the green – yet again – opens from that angle. An ill-conceived bunker added front left in recent times undermined Thomas’s strategic intent; Hanse Design’s swift removal of it was a welcome event.

The carry to reach the plateau in the fairway is shorter down the right but that leaves an obstructed approach shot. Better to seek the left side off the tee.

The ability to bounce balls in from the left is one of the best shots recovered during the restoration.

Fourteenth hole, 600/530 yards; Ever prescient, Thomas seemed to have an answer for everything. Take par fives, which are especially vulnerable to changes in technology. He has the first hole, which in one of his versions of ‘a course within a course’ plays as a par 4 to a front hole location. The double-dogleg eighth confounds golfers to this day and then we have here. Long hitter can attempt to reach the hole in two by knocking his tee shot over the bunker at the inside corner of the dogleg. The price of failure is crushingly high though, as the ground falls abruptly right toward out of bounds. As Hanse admiringly notes, the fourteenth green ‘…just hangs on the edge and the slightest miss likely means the ball ends up somewhere bad.’ Shackelford also cites this as an all-time favorite green and it is no surprise that this cunning three shotter is the favorite hole of several members. By the time the professionals come here in 2023, there is no telling how high and how far they will hit the ball. Regardless, this green complex will be more than ready to defend Old Man Par.

The fourteenth fairway turns right along this series of sunken pits to a green fiercely protected by the contours of the land.

Shackelford appreciates how the fairway sweeps left to right, yet the green goes front right to back left. It is certainly a design ploy of which we would like to see more. Even a mere pitch to the newly recovered right hole locations (like the one above!) is no bargain. A miss slightly right or long courts disaster as the ball might tumble as much as 50 feet downhill.

Fifteenth hole, 135/135 yards; Thomas’s design talent is evident on many levels: routing, variety, strategy, the list goes on. This hole stands front and center in demonstrating his genius because it was built on dead flat land without a shred of character. There was nothing. Yet, this connector hole needed to be built to display the character rich fourteenth and sixteenth. Three bunkers and a lengthy crescent shaped green conspire to create a one shotter with dramatic playing qualities that allow the fifteenth to hold its place alongside the other exemplary one shotters. On a big, brawny course like here (and coincidentally, Riviera), what a delight to find a short hole thrown into the mix late in the round.

The range of one shotters here is second to none capped off by this little beauty. Hanse considers this one of his favorite holes on the course, largely because it is ‘… a ton of fun to play on a regular basis.’

The challenge goes well beyond hitting the green, which is 43 yards in length. The little mound that was restored in the middle left of the putting surface ups the ante and 3 putts loom for the player who doesn’t find the correct section for the day’s hole location.

Sixteenth hole, 505/435 yards; Brilliantly routed, the sixteenth plays along the spine of a hill, with the tenth hole in the valley to its right and the eleventh in the valley to the left. As at the fourth at Rye Golf Club, the challenge boils down to hitting the ball both far and straight in two shots, a distinct weakness of most golfers! The confident, bold player on the top of his game delights in finding such a hole that repels the timidly/feebly struck ball. What a hole this most have been in the age of hickory golf as it would have required two stout blows. The same once again holds true as this hole now boasts a back tee of 505 yards.

Played high along an ever narrowing finger of land, the sixteenth asks the golfer to squeeze his tee ball past the left bunker and then avoid the right bunker eight yards shy of the putting surface.

Seventeenth hole, 455/410 yards; The course ends with three two shotters though the golfer may hardly realize that fact as they are all so different. From the elevated tee, the golfer is afforded a grand look down the fairway as well as peeks of the wash that borders the right side of the fairway. The green complex (i.e. the diagonal array of greenside bunkers combined with the angled putting surface that is broad rather than deep) favors the golfer who flirts with the wash off the tee.

Both breathtaking and strategic, the seventeenth asks the golfer ideally to first hit a fade off the tee and then a draw into the green.

This day’s hole location is one of the more reasonable ones. The same can’t be said when it is moved just beyond the far left bunkers! Note the bridge behind that climbs to the eighteenth tee.

Eighteenth hole, 500/415 yards; The Home hole is played over the same vast field as the first but headed toward the clubhouse. Without any natural features Thomas was on his own to liven the proceedings – and like the fifteenth he and Bell were up to the task. The fairway elbows left over an expansive Bell bunker and the winged green best accepts shots from the outside of the dogleg. An exception occurs when the hole is in the back right portion and then the golfer’s interests are better served from the left side of the fairway. Every good player at the club notes the day’s hole location before they commence their round and leave the first tee.

The Home green is canted and open in front to receive shots played from the outside of this slight dogleg left.

Good things happen when Gil Hanse and Jim Wagner come to southern California and see Geoff Shackelford. Witness their work together at Rustic Canyon some thirty miles away, which the author ranks among the handful of most enjoyable public courses in the country. Not just by coincidence, Rustic Canyon embodies many of Thomas’s design tenets, a sure sign of the admiration that the three have long held for The Captain. Pity other architects haven’t as readily embrace the work and writings of George Thomas. He was convinced that the best of golf course architecture was yet to come. Yet when you look at his work around southern California, you might well conclude he got more right, more often than any architect before or since. His ‘course within a course’ concept of playing from certain tees to specific hole locations with par sometimes changing remains as advanced and forward thinking today as when he detailed it in 1927. Regarding their work, Hanse sums it up nicely when he states, ‘At the end of the day it is Thomas’s work and we were just happy to be putting it back. I can tell you this though: By the end of the project, we were all much better golf course architects having worked at LACC and learned from Thomas. In fact, I took parts of what I saw and tried my best to transpose some of the ‘course within a course’ concepts into the Olympic Course in Rio.’

Thomas never got a Cypress Point or Pebble Beach site upon which to work. Yet, remember his quote at the start of this profile where he notes that ‘… there are many inland courses which are as fine as the linksland by the sea.’ How true did that statement turn out here?! On the North Course, the two received the best property they ever worked on with its abundance of natural features laced throughout and they capitalized on it to perfection in the later stage of their partnership. Save for the Old Course at St. Andrews, this parkland course may well exceed the golf required at all the other British Open rota courses. As such, Thomas’s fully restored North Course represents the pinnacle of parkland design and now Golden Age restoration.

Separated by a bank of roses from the first and Home holes, the Colonial Georgian clubhouse basks in the California sunshine as it lords over play.

The End

![The Park, West Palm (Lit 9) [2023]](https://golfclubatlas.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/IMG_7092-2-scaled-500x383.jpg)