Lookout Mountain Golf Club

Georgia, United States of America

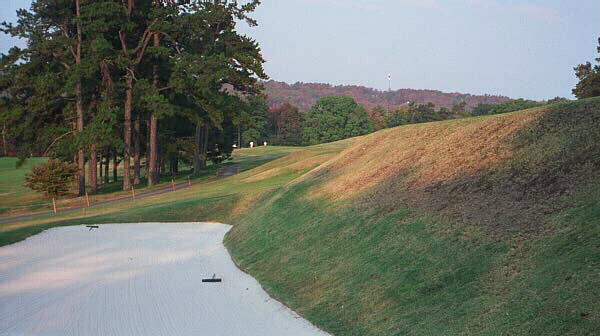

Raynor’s stairstep bunkers in a mountain setting

The revival of Lookout Mountain Golf Club is a story very much worth understanding.

Seth Raynor was at the height of his considerable powers when he passed away in 1927 at 50 years of age. He had projects across the United States, literally. From Hawaii to California to Florida, his talent had never been more in demand.

Prior to his death, Raynor produced numerous high profile courses that are highly regarded as classics to this day. Though not a golfer, his engineering background served him well and brought him much deserved recognition. For instance, few architects could have devised a way to pump the bay bottom to allow the construction of Lido GC. Also, the creation of the noted island Biarritz green at The Creek created much mention in technical papers.

So when Garnet Carter and Scott Probasco were interested in creating a golf course as the centerpiece to a 15 story, 300 room hotel located on Lookout Mountain, some 1,800 feet above the city of Chattanooga, they knew whom to call. The Fairyland developement (as it was called then) was to be a great mountaintop destination for the South, and beyond.

Upon seeing the site, Raynor’s immediate enthusiasm for the invigorating climate and sweeping views in all directions was partially tempered by the granite rock on or near the playing surfaces. His engineering skills would be put to good test here! According to historian George Bahto, Raynor routed the course three months before he died but never saw the ground broke. Charles Banks completed much of it but with about 25 other incomplete courses to finish (including Yale and Fishers Island), Fairyland never received the finishing touches such a unique site deserved.

With course construction costs nearing $400,000 (at the time, second only to Yale as the most expensive course built in the United States) and an ill-timed storm where eight holes were washed away after seeding, Raynor’s vision was to go unfullfilled. Starting with the Depression, Fairyland CC endured hard times and slowly fell from the public’s eye.

What a shame it would have been if such a site never realized its full potential! Pictured is the green for the 445 yard downhill opening hole.

So the story could well end, and Lookout Mountain would have joined the same sad fate as happened to so many classic courses in the United States (note: see Daniel Wexler’s recently published Missing Links). Thankfully, such is not the case.

Starting with a phone call that Brett Mullen, the Head Professional, made to Bill Coore in 1993, the Club began to realize that they had something special on their hands. Board members Doug Stein and King Oehmig formed a Raynor Committee in 1995 and, in order to best appreciate the opportunity at hand, they visited as many Raynor courses as possible. With such courses as Shoreacres and Chicago remaining true to Raynor’s work, they acquired a keen sense of their opportunity. As they noted in their Raynor Report to the club membership, ‘We have the spine-tingling privilege of playing golf on a masterwork by one of the ‘Grand Masters’ of American golf. But the reality is that we have an unfinished masterpiece.’

They continued to research the history of any alterations to the course. They interviewed King’s Dad (former Walker Cup captain and Bob Jones award winner Lew Oehmig), former greens chairmen, and even the man who ran the dozer in the early ’50’s when many of the greens were altered as they first converted the greens to bent grass. Importantly, they had Raynor’s original plans of the course on linen and some pictures of the original greens. These plans showed there to be 81 bunkers, covering a massive 266,000 square feet.

The Raynor Committee’s chore was now to find the right architect to sell the project of completing Raynor’s vision to the membership. Eventually it came down to Brian Silva, whose enthusiasm and knowledge of old classics would help convince the membership this was indeed the right path to pursue.

The first stage centered around restoring many of the bunkers on the original Raynor plan. With less than 20 bunkers remaining, and many of them even having been relocated to the wrong spots, the ambitious plans called for almost 50 fairway bunkers to be added that were shown on the Raynor plan but never installed by Banks.

As Brian Silva notes, ‘Given that many of the bunkers are perpendicular to the shot and have very imposing cross bunkering characteristics, it was never going to be an easy sell to the membership.’ Brian appreciated that ‘there are lots of projects where courses re-build all of their bunkers and add a few here and there, but I can’t say that I’ve heard of one where over 50 new fairway bunkers were installed while all the others were deepened/re-orientated in a way to make them play tougher.’

The sincerity with which the Raynor Committee went about gaining support from the senior membership forms nothing short of a ‘how-to’ model for other clubs to follow. In the end, the Long Range Plan was approved and work commenced in 1997. In addition to the bunker work, a number of tees were rebuilt and the imaginative green contours on the Alps and Double Plateau greens were recreated as best as possible from available information. The course re-opened for play in 1998 ahead of schedule and under budget. Stage Two involves restoring many of the greens to their original dimensions. For instance, by reclaiming the front left portion of the ninth green or the front right portion on the fifteenth green, intriguing hole locations will be brought back into play. Again, the original Raynor plan was invaluable in helping them to determine just how far to extend these ‘wings’ of the green.

Also, some of the more subtle interior green contours have been lost to heavy top-dressing and dragging with topsoil, which was the common practice after WWII for several decades. In addition, when the greens were converted to bent, they were done in circles in the center of the green pads, much as happened at Yeamans Hall. As Stein notes, ‘Hopefully, the greens will be fully restored at some point in the not too distant future.’ By doing them to USGA specifications, the greens will retain a firmness even in wet weather that allows for lower shots to be bumped in and chased back to certain hole locations, as Raynor intended.

The back to front pitch of the restored Alps green is similarly terrifying to that at Prestwick.

Further exciting plans exist. The Biarritz green may be brought forward to include the swale, the Short hole may once again become an island green surrounded by sand, and the Sahara bunker will front the Alps green. If those three highly distinctive Raynor holes obtain their full glory, along with recapturing some of his unique interior green contours, then Lookout Mountain will be Raynor’s most dramatic course – and be an unfinished masterpiece no more.

Holes to Note

Second hole, 430 yards; Originally the thrilling Home hole, this downhiller is visually dramatic off the tee with the golfer needing to skirt seven massive fairway bunkers that are in clear view – four bunkers line the inside of the gentle dogleg left with another three on the far side. The approach is to a typically (and wonderfully) gigantic 6,900 square foot Raynor green, whose back to front pitch places a preminum on keeping the approach below the hole.

Fourth hole, 225 yards; A Biarritz hole of the highest order, with the right bunker as deep as twenty feet (or as Brian Silva points out, the green is as high as twenty feet). Raynor’s drawings clearly indicate that the five foot swale was not initially intended to be kept as green but hopefully, the current Club Board can convince the membership to extend the green some forty yards toward the tee.

This daunting bunker guards the right side of the Bairritz green.

Fifth hole, 390 yards; A blind drive to a left to right sloping fairway is actually the easier of the two shots. The approach is to a ‘dustpan’ green (it is not quite a punchbowl as the front is open) with a fearsome amount of back to front pitch. Anything above the hole is dead; conversely, anything short of the green is likely to be gobbled up by a fifteen foot greenside bunker. What’s a golfer to do?

The diabolical 5th green complex

Sixth hole, 125 yards; Perhaps the most intimidating Short hole in Raynor’s portfolio, the green is perched on granite and is the consummate island target with eighteen foot drop-offs right and long. The object is simple: hit the putting surface or else. Such was always Macdonald’s intent for his Short holes and Raynor pulls it off brilliantly here. Interestingly enough, one of the complaints about the greens at Fairyland in the late 40’s and 50’s was that they were ‘surrounded by these steep slopes, and some of them looked like top hats.’ Thankfully, such green complexes as at the sixth were too formidable to be bulldozed by less well informed committees.

The intimidating Short hole – hit the green or else!

The eighteen foot drop-off is best appreciated from a distance.

Tenth hole, 565 yards; An ingenious three shot Cape hole that follows the sweep of the hillside from high right to low left. Seven fairway bunkers dot the way but not handling the sloping fairway is generally what keeps the tiger golfer from getting a ‘four.’

Genuine fairway bunkers (!) on an American course – these dot the way along the 10th, as seen from the 13th tee. Before the restoration, the Cape hole had no such bunkers.

Eleventh hole, 400 yards; A spectacular Alps hole, with the blind, boldly contoured green aligned to the mountain peak in the far distance. The thrill of scrambling to the top of a hill to see where your approach shot has gone is something that modern architecture sadly lacks.

Thirteenth hole, 200 yards; In a unique touch, this Redan plays downhill some 25 feet. Distance judgement is tricky but crucial as the deep bunker behind the green was faithfully restored and is no place to find oneself. Silva is particularly pleased with the removal of a flash bunker that had been installed at some point right in the right side of the kick-back area and how they reworked ‘the approach of the Redan to get a better Indy 500 turn at the right front of the green so that folks can play the appropriate shot to the green.’

Imagine the ruined playing characteristics with a bunker high right of this Redan green vs how it now appears!

Seventeenth hole, 395 yards; Patterned loosely after the eleventh at National Golf Links of America, this Double Plateau green must be seen to be fully appreciated. Silva says ‘we compared notes on double plateaus we had seen – Chicago, Essex County and Hackensack, among others – and combined this information with members’ pre-flattening recollections of the original seventeenth in our re-design.’ Silva’s research paid off handsomely and numerous interesting hole locations make this hole. The back hole location is used every fourth day and is a fine example of an architect dictating that a low trajectory, running ball is optimum. Also, Silva’s attention to aligning the grass face of aforward bunker near the tee to that of the fairway bunker in the distance that is really in play is to be commended.

Notice the high left plateau, followed by a dip and then the back plateau with the day’s hole location

Eighteenth hole, 385 yards; Banks considered this the finest hole on the course from a ‘technical golfing standpoint.’ By that perhaps he was referring to the risk/reward element of the tee shot. The extreme sides of the fairway offer the more level stance to approach the green and the better angle but that is exactly where the trouble lurks. On the left side of the fairway were bunkers/broken ground and on the right side, the out of bounds stakes for the public road threaten. For those who play it ‘safe’ and head down the middle with their tee ball, an awkward stance with the ball above your feet will greet the golfer and make getting the approach near the hole on this contoured green difficult indeed.

Banks considered this hole perfect from a ‘technical golfing standpoint.’

This is the final point that must be made of the challenge at Lookout Mountain: more so than even Yale, the golfer battles uneven stances for his approach shot. Mind you, nothing that is silly but rather just enough to test a golfer’s true knowledge of his swing.

The setting of Lookout Mountain GC is unique in the world of golf, and so can be the course. Much work has been successfully done already to return the Raynor features to this course, but work remains. The Board, Brian Silva and Superintendent Mark Stovall are working hand in hand. Trees are being felled, vistas are opening up, native fescues are being encouraged to give the course additional texture. All in all, it is one of a handful of most exciting reclamation projects in golf. With the right attention to detail, its success will yield a course of uncommon pleasure for golfers of every level – and a must-see for all Raynor fans.

![The Park, West Palm (Lit 9) [2023]](https://golfclubatlas.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/IMG_7092-2-scaled-500x383.jpg)