The Kittansett Club

Massachusetts, United States of America

… inland ones like the 12th with its intriguing old school bunkering, Kittansett epitomizes the bountiful charms of New England golf.

The Kittansett Club hosted the Walker Cup in 1953, just one indication of how long it has been held in high esteem. Indeed, many consider its stature second to only The Country Club within the golf rich state of Massachusetts. Yet, when the author first played the course in the fall of 1985, such recognition seemed more attributable to its romantic location than holes of character replete with interesting features. True, the celebrated one shot third lived up to its pictures but the others were more conventional than inspiring. That impression has thoroughly changed, thanks to a twenty-year, meticulous restoration project carried out by The Kittansett Club with architect Gil Hanse that has seen William Flynn’s design magic be returned to the course.

The transformation began in 1998 and can be distilled into three vital areas: tree culling, recapturing unique features and green reclamation. Prudent tree removal has seen the club re-establish its seaside connection that black and white photographs showed it once enjoyed. Large pockets of the property, especially the southern third where the peninsula narrows, were allowed to breathe as trees were removed near holes two, four, sixteen, and seventeen.

With the trees and brush removed, Kittansett once again takes full advantage of its dazzling location at the end of a peninsula. William Flynn’s routing keeps the golfer off-guard at this windy site as he set each of the five holes above at a right angle to the prior one.

In the mid-1990s the sixteenth (seen left in the photograph above) was enclosed by a wall of trees down the left that also formed a solid backdrop behind the green. Now, Buzzards Bay is in full view from the tee and the southern point is again open and seaside in nature. The hole’s playing merits have become starkly evident and only a fool would fail to recognize it for what it is: one of New England’s best holes. Not surprisingly, Hanse was proven correct when he told the board early on that, ‘Your golf course is so well designed and so carefully laid out that the removal of trees will only sharpen the focus on the design of the golf course. In so doing, all of the strategies, options, and punishments that exist simply in the layout will be more clearly revealed.’

Vegetation clearing also produced views of Buzzards Bay from many interior holes (namely five, six, eleven, fourteen, and fifteen) whereas none were afforded in the 1990s. Put another way, the golfer now sees the water from a majority of the course, eleven holes to be precise. Yet, such work is more consequential than ‘just’ enhanced visuals. Wind is more prevalent across all eighteen holes and the turf throughout has benefited from increased air flow and sun. When the holes were forested, the fairways were soft and the golfer was robbed of playing the kind of low running shots that this 1922 design encourages. After new drainage and tree removal, all playing options are again viable. In the members’ eyes, this has been the most dramatic improvement but like so many clubs, tree removal was the most contentious issue and the slowest to be embraced.

As trees came down, distinctive design features were either uncovered or recaptured, including many of Flynn’s novel grassed-over rock formations and cross hazards. Previously, several of the formations were shrouded by trees. No more! According to Hanse, ‘We removed hundreds of trees from the various mounds around the course. These were rock and debris piles from construction that Hood used as features to line many of the holes and as diagonal hazards on others. For the most part they had been swallowed up by the tree lines over the years. We cut back the trees and restored native grasses to the mounds for what is perhaps the most unique feature at Kittansett. When we got there you could barely see the mounds.’

Wayne Morrison, Flynn expert and co-author of Flynn’s biography entitled The Nature Faker, shares this on the design and build of Kittansett:

Kittansett is easily discernible as a Flynn design as the strategic use of shot testing, angles, bunkers and wind are very sophisticated and very much a part of his overall design portfolio. The site is spectacular from an aesthetic and weather impact perspective, but it proved disastrous in terms of the nature of the soil, accounting for the one-off nature of the course. The vast amount of rocks (see photograph below), many boulder in size, led to the necessary irregular and appealing looking mounding throughout much of the course, necessity being very much the mother of invention. Little option existed to move the rocks off property so the only answer was to mound them on site. The strategic use of such mounds was brilliant, as it was both economical and strategic. However, let me add that unlike nearly all of his other projects, Flynn’s construction crew was not involved at Kittansett (therefore, no Toomey-Flynn attribution is possible). Fred Hood deserves the credit for the overseeing the construction of the course and the low profile course that seems so at peace with its environment is due in part to his sensibilities and ingenuity.

Flynn’s imaginative design and Hood’s oversight of implementing Flynn’s ideas into the dirt turned Kittansett’s rocky conditions from being a negative into a positive.

Morrison notes how Flynn’s own drawings were very specific in calling for such mounds. In terms of their actual physical creation, it was Fred Hood (who owned the property and hired Flynn) who was on site and drove the construction process. Kittansett was Hood’s passion and Hood oversaw the presentation of the course for an additional twenty years until his death in 1942. Many of the world’s great courses evolved over several decades (e.g. National Golf Links of America, Oakmont, and Pinehurst No. 2) and Kittansett benefited from Hood’s devotion.

While Kittansett’s greatest natural blessing was its dreamy coastal setting, it didn’t possess roly-poly landforms of the sort that Donald Ross so frequently enjoyed in the northeast. Therefore, it was incumbent upon Flynn to add playing interest. He did so not only with the grassed-over rock formations but also with an elaborate bunkering scheme. Be it large cross hazards (we ignore the definition change of 2018 to ‘penalty area’ and continue to use the time-honored term ‘hazard’) that bisect fairways or small bunkers cut into mounds, Flynn employed hazards in every conceivable manner.

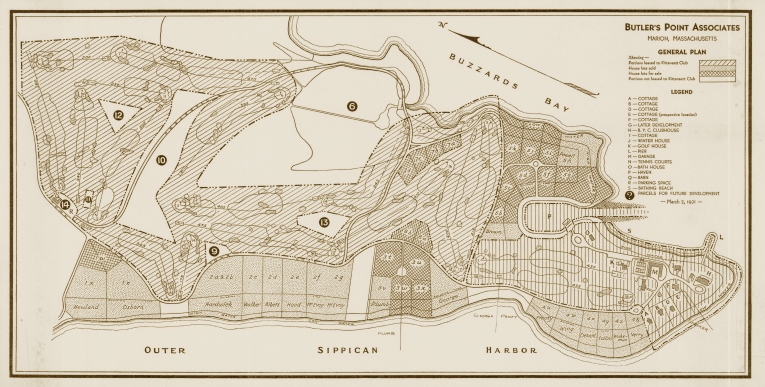

Morrison shares this original plan of the course that, among other things, shows the number of interrupted fairways and Flynn’s elaborate bunkering schemes.

Alas, over time, Flynn’s standout bunkering had lost its original size and rugged appearance, so Hanse and design partner Jim Wagner, working side by side with Green Keeper John Kelly and his crew, reconstructed every bunker to its original shape and size. Fine fescue sod was largely used for the bunker faces and wherever possible they kept patches of native grass, moss, and even rocks to add instant maturity. Three bunkers that had been lost were brought back: one to the left of first fairway in combination with the cross rough, another in the middle of the second fairway, and one to the rear of the fourteenth green. Not surprisingly, two of those three bunkers had been in the direct line of play. Another example comes at the ninth, where Hanse extended the bunker back some forty yards toward the tee. In 1998, the bunker was only greenside.

Flynn’s sandy waste areas aren’t too problematic from which to recovery and other times like the pit bunker on fourteen, the golfer isn’t guaranteed a full swing. Understanding which hazards can be challenged and which will produce a meek chip out is part of the art form of learning how to play Kittansett properly. Such knowledge isn’t revealed after just one or two rounds but rather with time.

Typical of Flynn, a number of fairways are interrupted by broken ground or sand (e.g. the first, second, ninth, seventeenth, and eighteenth) or cross hazards that sweep in from one side or the other (e.g. the sixth, seventh, tenth, twelfth, fifteenth, and sixteenth). 80% of the non-one shot holes are so configured. Such well-placed hazards make Kittansett – guess what – a placement course. In this day when modern courses feature 60+ yard fairways, it is a delight to find a design like Kittansett that identifies sloppy execution while rewarding tactical golf. Simply put, the golfer needs to find fairways to hit the intermediate size greens.

The reclamation of the green pads was the final piece of course’s metamorphosis to a thinking man’s course. Over 13,500 square feet have been recovered to date and appealing interior contours revealed like the back of the fifteenth green. Still, as things stand now, the greens only average 4,683 square feet in size. Throw in some wind and they indeed become tough targets to find consistently. More green fine-tuning is underway, especially in regards to between the green collars and bunker edges. As false fronts have been restored such as on holes seven, eight, ten and seventeen, an appreciation of the ground game has only mounted. Seeing the ball interact with the ground and slowly roll this way or that is an underpinning to sea-side golf.

As seen from the right of the 15th green, Hanse reclaimed putting surface around the high right and back. This back hole location didn’t exist five years ago. At 6,460 square feet, it is the largest green at Kittansett. To put that in perspective, it might be the smallest green on a well presented Raynor course!

Several of the course’s most vexing hole locations have been returned (back right on eight, back left on fourteen) and more will be unveiled as the work continues. The knob sixteenth green saw the putting surface extended to the very edges of the green pad where its soft shoulders effectively make the green behave as a smaller target!

The culmination of Hanse Design’s work and Kelly’s greenkeeping has reignited an appreciation for Flynn’s distinctive design. Instead of narrow playing corridors through trees, Flynn’s work is once again something much more multi-dimensional, intricate, and exhilarating, as we see below.

Holes to Note

First hole, 450 yards; Opinions as to what constitutes an ideal opener fall at either end of the spectrum. Some prefer ‘a gentle handshake’ to ease into the round. To the author, the problem is that if you mess it up, things could rapidly unravel. Far better to tackle a bit of bruiser, like the first at Kittansett, where even if a bogey is carded, no real harm is done. As is repeated throughout the round, hitting the fairway off the tee provides the foundation for clearing a cross hazard with one’s second. The first normally plays in a left to right crosswind and yet the left third of the fairway is the ideal spot from which to approach the green. Thus, the player who can shape the ball enjoys an acute advantage at Kittansett, which is one of the reasons why the Old Guard love playing here. Suffice to say, the player who hits a low controlled draw down the first is likely to prove a worthy opponent.

This view down the 1st conveys an important fact: Kittansett represents one of the game’s finest strolls as it possesses the ease of walking a heathland course void of hilliness, coupled with the thrill of being in a coastal setting (note the plethora of seagull feathers).

Second hole, 445 yards; The first two holes sum up the construction philosophy for the entire course and highlight what the golfer can expect: low profile tee pads, lay-of-the-land architecture tee to green, any mounds created are invariable within the playing corridor (not haplessly placed on the sides where they don’t influence play), and an intermediate size green built up in part for drainage reasons. Additionally, ground game options dominate throughout. Unlike the first hole, length is not the primary issue at the second as it generally plays downwind. Rather, can the golfer successfully judge how far short of the 4,198 square foot green to land his approach? It is a timeless question that the golfer never tires of solving and to do so, he must fit it between two front greenside bunkers.

Above is a common sight at Kittansett in that the golfer needs to carry broken ground with his approach. Additionally, note the lack of framing around the green, which is located but a few paces from Buzzards Bay. Keen judgement and steely nerves are required to chase after back hole locations.

Third hole, 165 yards; Apart from the obvious, what the author enjoys about this world famous hole is the random treatment that befalls tee balls. The typical summer wind is left to right and many a golfer misjudges its effect, especially early in the round. Hence, the green is frequently missed. One tee ball can land on the beach and gain a perfect lie on a slight upslope where the recovery splash is straightforward and a par the result. Another might land in a heel print on the beach and that player might struggle mightily for a bogey. Such serendipity is as nature would have it and how each man reacts is telling.

Ironically, the course’s most famous hole uncompromisingly calls for an aerial approach; every other green allows for a run-up. Yet, such is the one-off, compelling nature of the 3rd that it is no wonder why it leaps to mind when thinking of Kittansett.

Seen from the edge of the green back toward the tee on the point, the golfer can only hope that an errant tee ball finds a good lie on the beach.

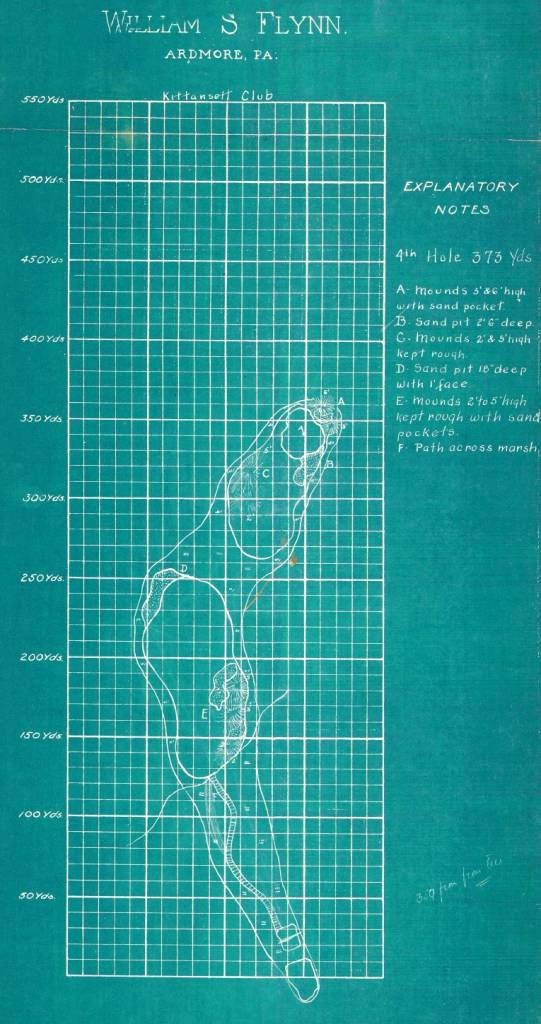

Fourth hole, 375 yards; In a manner similar to St. Andrews, the first and last holes emanate and return to the clubhouse across a shared field, some 115 yards wide. That was sufficient for Flynn to place two playing corridors but nowhere near wide enough to have considered returning nines. Therefore, Kittansett enjoys a venerable out and back routing. A knock against such a configuration is that the wind punishes one way while the player rides it in the other. If the holes don’t shift directions, then the golfer can too easily establish a bead on the wind and play his shots with growing confidence. To avoid that, Flynn provided holes that either dogleg or bend sufficiently to require the golfer to make continual adjustments. Indeed, the fourth kicks off a quartet of holes that ‘elbow’ from tee to green. However the wind impacts you on the tee, it is guaranteed to bother your approach shot differently.

This handsome mound was once treed and gives way to a typical Kittansett green: open in front, intermediate in size, and dropping off three feet in the rear.

Fifth hole, 445 yards; Here’s a textbook example of a central hazard adding great interest with a large bunker literally splitting the fifth fairway and being located precisely where the golfer wishes to place his drive. Oddly, while The Old Course at St. Andrews has a multitude of such hazards, modern architects have been reticent to employ them. Beginning in the 1960s with man able to shape the earth in any manner possible, an odd notion took hold that the fairway was meant to be a ‘fair way’ that extended trouble free from tee to green. This appalling break from the Golden Age and the writings of Tom Simpson and others saw hazards placed to the sides and the task merely to drive it straight. Classically, the central hazard is a quandary, carried in certain winds, layed up to or skirted to the left or right under other conditions. The fifth’s central bunker presents those very appealing and perplexing options. It is another of Kittansett’s charming features that emphasizes that one is playing a Golden Age design.

Sixth hole, 425 yards; During construction and per Flynn’s direction, Hood grassed over several piles of rock and debris to produce a unique diagonal hazard on the inside of this dogleg right. By being in the line of play, such mounds actually dictate strategy. Hanse made the feature relevant again by extending the low profile tee backwards to pick up an additional 30 yards. Such a move was not a mindless attempt to add length for length’s sake (like Riviera’s twelfth hole) but brought a specific feature back into play. Indeed, the new tee actually shortens the green-to-tee walk from the prior hole, so this was a shrewd move on two counts. All told, Kittansett measures 6,935 yards in 2019 as compared to 6,545 yards twenty years earlier.

By pulling the tree line well back from these mounds at the 6th, and restoring the fairway beyond, the golfer now seeks an advantage by carrying them from the tee. In the 1990s, every golfer was forced to play left. This is but one example of how playing angles have been reintroduced.

Seventh hole, 545 yards; An auspicious moment is reached at the seventh as the golfer turns his back to the bay. How much will he regret the inland foray? If it is ‘considerable,’ then the architect has failed. Happily, for the author, the answer is ‘not at all.’ In fact, the loop from seven to twelve has become a favorite section. It begins here with the monumentally improved seventh, previously claustrophobic with trees pinching in from both sides. Today, its expansive nature and intelligent bunkering pattern make it a highlight of the round and a three shot hole where the second is once again meaningful.

The second shot on too many Golden Age par 5s is fairly commonplace, with the need merely to advance the ball. That is not true at Kittansett, especially the 7th where the above bunker intrudes into the proceedings 170 yards from the green and …

… farther ahead, a long cross hazard cuts across the left half of the fairway some 100 yards shy of the green.

Eighth hole, 210 yards; Kittansett’s routing enjoys more than a passing resemblance to The Old Course. The first and last holes play across a shared field, there’s a ‘crook’ near the turn and two one shotters (eight and eleven at both venues) that go in opposite directions to navigate a tricky part of the property. At Kittansett, Flynn expertly used the eighth to get the golf into the property’s far corner and eleven to adroitly navigate out. Both holes emphasize Flynn’s philosophy of placing hazards directly on the intended line of play. Over a full playing season, it would be interesting to see how the one shotters play compared to one another. While the third is the most famous, it might well prove to be the ‘easiest’ of the quartet, which is saying something. One of the best hole location that resulted from the green reclamation is found here where Hanse expanded the back right plateau.

The long one shot 8th shows a favorite design ploy of Flynn: a short bunker pulled 30 to 40 yards off the putting surface on holes that are approached from 200+ yards.

Tenth hole, 350 yards; Flynn designed Kittansett in the age of hickories. When he positioned a superb diagonal row of grass-covered rocks in the fairway, he did so at the appropriate distance for the equipment of the time. No surprise to find the farthest and tallest mound must be carried to achieve the optimal angle into the green. However, the far mound was only 190 yards from the back tee, and with today’s equipment, the rock formation had lost its strategic importance. Sliding the tee back farther wasn’t an option so in the fall of 2019, Hanse Design essentially picked up and moved the rock formation an additional 50 yards away from the tee. As the tee ball plays uphill, members will have something new to mull over during the 2020 season; carrying the newly located mounds is no longer a given. No doubt Flynn and Hood would approve of the move as the mounding works in perfect concert with a pair of bunkers along the right to give this short two shotter bite off the tee. Hanse Design did the same at the sixth, pushing that diagonal formation back as well. Combined with their work here at the tenth, it is a sterling example of Kittansett’s design being as relevant and challenging this century as it was last century.

Eleventh hole, 255 yards; Interestingly, the two greens with the boldest contours are found on one shot holes that exceed 200 yards in length, here and at the eighth. Meanwhile, modern architects tend to reserve their wildest greens for short holes. Talk about a different approach! At Kittansett, its two most severe greens make their respective holes much more than long slogs as the invariable recovery shot is often both fascinating and delicate.

… a bullet three wood that just carries it sends one’s ball scampering down the slope and onto the open green. Today’s hole location is front left but when it is back right, using the slopes to access such hole locations is richly rewarding.

Twelfth hole, 440 yards; If it wasn’t for the third hogging the spotlight, the twelfth would be much better known as it is a master class in playing angles, featuring an impressive fairway bunker that pushes the golfer right, from where he has to carry a cluster of mounds and bunkers. The golfer who stays left is rewarded with a simpler approach and better optics.

Flynn expertly positioned the bunker in the foreground between the tee and green. A quandry is presented as the closer the golfers stays to it, the easier his approach shot. As he shys right, the hole becomes progressively more difficult as the bunker complex farther ahead obscures a view of the green.

The high backsides of the bunkers are evident in this view back down the 12th. In some ways, the bunkers remind the author of those at Walton Heath in that the bunker walls are built up versus the bunker floors being built down.

Thirteenth hole, 390 yards; Since the 2008 financial crisis, restoration work has been a dominant theme in North America as clubs sought to get their biggest asset (i.e. the golf course) in order. Exceptional work has been done coast to coast with scores of courses dramatically improved. Yet, there aren’t too many instances where a hole goes from being in the bottom third pre-restoration to rising into the top third post-restoration. Kittansett potentially has two (!) such holes as the seventh and thirteenth join the sixteenth as most improved in the eyes of the author. Flynn designed the thirteenth as a teaser position hole, bending right past a series of attractive bunkers and mounds. The tiny, narrow green was ringed by sand and was best approached from the inside of the dogleg. In 1985 when the author was first here, the hole lacked merit; it was tree-lined to the point that approach shots from the inside right of the fairway were walled-off, necessitating a rifle straight drive to the outside of the dogleg. Only that one shot would suffice and that is the definition of uninteresting architecture. There was no deliberation as to what club to hit from the tee, where to place the ball in order to best access the long oval green or any worry about wind, which the forest muted. Today, the golfer enjoys multiple angles and club selections from the tee. Hoisting one’s short iron approach is no bargain either as the deforested hole/green is only sixty yards from the bay. Kittansett’s sub-400 yard two shotters (e.g. the fourth, tenth, thirteenth and seventeenth) play an integral role in making Kittansett a delight to play on a frequent basis.

This view from inside the dogleg was once of tall, thin, undistinguished trees. Now the fairway again doglegs around a marvelous bunker and mound complex.

As seen from behind, the miniscule 2,966 square foot 13th green is a vexing target to find, even on a calm day.

Fourteenth hole, 185 yards; Generally, this one shotter plays downwind. When the hole is in the front or right portion of the green, the play is straightforward but if the hole location is back left, the hole calls for an exacting draw. Too long or a little short leaves a pesky pitch from sand or long grass.

The kidney shaped green affords hole locations as hard or as easy as the club desires. The restored back bunker is barely visible above, and is the course’s deepest greenside bunker.

Sixteenth hole, 410 yards; A panoramic view of great beauty unfolds from the tee and stands in stark contrast to the wall of evergreens to the left and behind the green that masked the coastal setting when Hanse arrived in 1998. From a design perspective, the real marvel is found over the last seventy yards: a pair of bunkers pinch the fairway from either side and stand sentinel over a Biarritz style swale that swoops down before rising to the small bunkerless green, perched some four feet from its surrounds. This green complex enjoys design characteristics of Macdonald as well as Ross’s infamous turtlebacks at Pinehurst No. 2.

The two bunkers well short of the raised green pad muddle one’s depth perception and make hitting the 4,282 square foot green all the more difficult.

The prospect of an up and down from around the 16th green probably constitutes wishful thinking more than reality.

Seventeenth hole, 390 yards; Typically played into the prevailing wind, the seventeenth often times – shockingly – requires a long iron or utility club for the approach. That the approach shot is from an uneven lie to an elevated horizon green does little to assist the golfer in successfully finding the putting surface. As at St. Andrews, the penultimate hole is perhaps the course’s sternest test while the Home hole offers consolation. It’s the author’s favorite kind of pacing for a finish.

As seen from this aerial looking back down the 17th, the fairway is bisected by wetlands some 300 yards off the tee. An approach from the right portion of the fairway is ideal.

Kittansett’s allure as a feature rich design has been re-established as the club’s restoration project nears its final stages. Its appeal stands in marked contrast to many modern designs. At some point this decade, architects started pandering a bit much to the player by offering excessively wide fairways. Lost was the need to play positional golf and hit less than driver on the odd occasion. Additionally, as modern greens expanded to match the course’s scale, a variety of fiddly little recovery shots were replaced by the monotony of long putts. Somewhere in the mix, the pendulum swung too far with one playing style (the bomber) becoming favored over another (the tactician).

Kittansett is different and strikes a better balance between tempting the player to play boldly while still meting out a penalty for rash tactics. Pressure is applied on the tee, as the golfer is keenly aware that a missed fairway diminishes the prospects for hitting the intermediate size green. Errant approaches don’t miraculously find such targets but rather leave a variety of interesting recovery shots. In short, no one playing style is favored at Kittansett. The thinking golfer who positions his ball well off the tee invariably has the option to chase a ball onto the green. As such, Kittansett represents the rare design that is a delight through all stages of life. At the same time, this much is for sure: the golfer who develops the composure and skill to play well here will find that his game travels well anywhere in the world.

Located seaside, the short game area is a welcome addition as the player is likely to miss more greens in regulation at Kittansett than normal.

GolfClubAtlas.com very much thanks Todd Richins for the use of his photographs throughout this profile.

5th hole, 410 yards; A text book example of the benefits of central hazards adding interest to a hole, two bunkers are found in the fairway just where the golfer might wish to place his drive.

The right bunker in particular was expanded to its original size and once again now grabs the eye of the golfer on the tee and forces him to make a decision. Note the rough edges around the bunker.

6th hole, 390 yards; An unique diagonal hazard off the tee, Hood grassed over several piles of rock and debris on the inside of this dogleg to the right. While the stronger golfer can make the 230 carry over this hazard, Hanse has plans in with the Club to establish several new back tees, the 6th being one of them. The addition of such tees is not a mindless attempt to add length for length’s sake (as at Riviera’s 12th hole) but is being selectively proposed to bring such specific hazards back into play.

These grassed-over rock and debris piles are once again a distinctive feature of the design.

10th hole, 345 yards; Two new bunkers were added by Hanse to the course, one of which is found on this hole some twenty paces from where Flynn had originally placed one. Hanse’s bunker is at the 235 yard mark from the tee while Flynn’s is at the 215 yard mark. The twenty yard difference is obviously brought about by the never ending gain in technology and once again, the golfer has to contend with the grassed over rock formation in the fairway which pinches the fairway toward this pair of bunkers.

Golfer’s initially steer away from the grassy formation in the fairway only to find themselves in one of the now two bunkers that line the right of the 10th fairway.

11th hole, 240 yards; Interestingly enough, the two greens with the boldest contours are found on one shot holes that exceed 200 yards in length, here and the 8th. Such an approach is long gone from most modern architecture where ‘fairness’ seems to rule the day. As it is, these two severely tiered greens make their respective holes much more than just a long slog as the invariable recovery shot is often fascinating.

The left side of the 11th green is three feet higher than the right side and working a ball on to the lower right shelf is one of the most enjoyable shots on the course.

12th hole, 395 yards; One of our favorite two shotters in New England, the 12th features an impressive fairway bunker that pushes the golfer to the right, from where he has to carry a right hand greenside bunker. The bold golfer who plays down the left side of the fairway is rewarded with a simpler approach.

Most golfers shy to the right from this bunker, and from there the hole gets progressively tougher.

16th hole, 400 yards; When Hanse arrived in 1998, the wall of dense evergreens to the left and behind the 16th green masked its links setting. A contingent within the Club had mighty reservations regarding felling those trees but in the end, down they came. And now the sweeping views of Buzzards Bay is often praised by those same members as the most dramatic improvement. The challenge of the hole is increased as it is further exposed to the elements where the golfer is again asked to hold a small, raised target.

Believe it or not, Buzzards Bay was barely visible from this green in 1998.

17th hole, 395 yards; Considered the longest sub 400 yard hole in New England, the 17th often plays into the prevailing wind and as such, requires a long iron or even wood for an approach from even the best player. The fact that the approach shot is from an uneven lie to an elevated horizon green does little to assist the golfer in hitting it.

The general questions posed at Kittansett are how can the golfer best a) hold the small greens and b) use the wind to work the ball toward the hole locations. Certain hole locations make the course a bear and are no doubt used when Kittansett hosts important events. Other locations make for a more straightforward proposition. This degree of flexibility is admirable and comes without Flynn/Hood ever having to resort to any goofy features.

The one shot 14th generally plays downwind. When the hole is in the right front of the green, the play off the tee is straightforward. When the hole location is back left, the hole calls for an exacting draw. Too long and the golfer will find himself in a newly created/restored back bunker.

Flynn/Hood’s design at Kittansett enhanced the general rugged New England features through their innovative grass formations and ragged bunkering. In addition, the greens are exacting targets that require the golfer to invent shots as required by the wind. With its variety of features and links characteristics fully restored, Kittansett once again provides the kind of challenge that every true golfer relishes and demonstrates that such golf can still be played on this side of the Atlantic.

![The Park, West Palm (Lit 9) [2023]](https://golfclubatlas.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/IMG_7092-2-scaled-500x383.jpg)