Inverness Club

Ohio, United States of America

The golfer heading to the Inverness Club passes flat city block after flat city block. Little does he suspect the treat he is in for!

When golf was initially played here in 1903, the course was well removed from Toledo and truly out in the country. Yet, the land with its river valleys, plateaus and unique landforms was so compelling that it made the trolley ride well worth it. Local Bernard Nichols is given credit for the nine holes, though one must presume that Inverness’s first club president, the fascinating S.P. Jermain, had a hand in the design as well. Jermain is one of golf’s great, untold stories. His resume includes the creation of Toledo’s Ottawa Park in 1899, the seventh municipal course in America. In 1907, he condensed and simplified the Royal & Ancient’s rules into the ‘American Code of Golf’, which helped novices on this side of the pond understand the rules that governed play. In the early 1920s, he was vocal in calling for matches between the United States and Great Britain, contests that eventually became known as the Ryder Cup!

What a friend of Inverness and the early game! He helped find today’s site and his clear understanding of its attributes is evident from his description of Inverness in the June 1920 issue of Golf Illustrated:

In this spirit began and continued the development of those dune-like-formations which possessed a soil most favorable for the growth of the bent grasses characteristic of the sea-side links. While now far inland, the waters of that vast ocean which followed the subsidence of the glacial floods had, in those ages long past, here flowed and ebbed, creating the remarkable natural golf conditions which place Inverness in a unique position as an inland course. As a rich legacy of the ages, a sandy loam predominates throughout Inverness region with a clay sub-soil, whereby the moisture is ideally retained.

Bobby Jones famously extolled that there is ‘golf, championship golf and major championship golf.’ His comments were largely about the mental challenges for a competitor but can be applied to clubs and their golf courses. Inverness throughout its illustrious history has hosted major championships and this affinity has shaped not only the culture of the club but also the nature of its golf course. Without this penchant, the 18 holer at Inverness might be just another pleasant, compact, Midwestern retreat. However, the requirements of major championship golf have made it something entirely more elaborate.

The club initially acquired eighty acres and the first nine holes played in and out of the river ravine. They measured 3,115 yards and the nearby corn field was identified for a second nine. According to Inverness’s very readable centenary club history penned by Dave Hackenberg and Mel Fultz, W.J. Rockefeller assisted Nichols in the construction and became the long-standing, influential Green Keeper at Inverness. Rockefeller apparently oversaw the addition of more holes in the mid-1910s but Inverness was still not ready for championship golf. That began to change in 1916 when Ross was invited to submit plans for an eighteen hole course that would be fit to host the best. Work proceeded over the next two years with a big, hands-on assist from Rockefeller. The existing holes were completely re-vamped and the nucleus of today’s course was born. In part because of a clubhouse fire in 1918, it is unclear to this day what existing corridors Ross might have utilized. What is certain is that additional land was secured including that which houses today’s imperial fourth and seventh holes, so those are categorically Ross creations. When Ross finished his work, the two nines started on the west side of the clubhouse and finished to the east. Chris Buie, author of The Early Days of Pinehurst, shares the architect’s sentiments about the merits of returning nines:

One of the desirable shapes for a piece of golf property is that of a fan. It gives you the opportunity to place your clubhouse in the center or handle of the fan and lay out two loops of nine holes each on either side of the handle. The 1st tee, the 9th green, the 10th tee and the 18th green are then all right in front of the handle near the clubhouse. You can play 9 holes without cutting in on other players. When the course is crowded, players can be started on either tee #1 or #10, which greatly relieves congestion. This layout affords another rather pleasant feature, as members can stop after 9 and have refreshments.

Jermain and other founders of the club appreciated what a big event would mean for their hometown and persuaded the United States Golf Association to bestow the 1920 U.S. Open to Inverness. The New York Times reported in 1920 that Ross …‘gave personal supervision to the most minute changes, such as the widening of a trap, the lowering or raising of a bunker and the mowing of long grass.’

History has marked this as a crossroad in golf; great American players like Bobby Jones and Gene Sarazen emerged while the English legend Harry Vardon would soon call it a career. Ted Ray won the tightly contested event, in part because of how he dominated Ross’s curling, risk-reward (now defunct) seventh hole. Rather than play safely to the right, Ray, known for his prodigious length, took a short cut, strangling a birdie each round. Though Ross’s seventh was fraught with trouble for those that strayed left, the hole could be had – even in 1920 with hickory golf clubs.

Inverness regularly sought and was granted U.S.G.A. championships including the open in 1931, 1957 and 1979. For each of these events Inverness strived to improve their golf course so that it would remain a major challenge. On each occasion preeminent designers were employed to enhance the Ross layout. In the late twenties, A W Tillinghast did some bunker and green work ahead of the 1931 national championship. Dick Wilson added and modified a dozen plus bunkers to test the world’s best in 1957. George and Tom Fazio were called in to make ‘minor tweaks’ to the severe slope of the seventeenth green in anticipation of the 1979 championship . Their visit extended much farther after they suggested ways to reduce the congestion near the eighteenth tee where a number of greens and tees converged. After much discussion, the board endorsed the Fazios’ plan to condense Ross’s sixth, seventh and eighth holes into one (today’s eighth) and to build three new holes (third, fifth and sixth) on additional property at the southern end.

At the time, The Ross Society had yet to be born, The World Atlas of Golf was only just about to emerge and Golden Age works were not heralded for what they stood for. The Club did what countless other clubs did during that time period: they pursued false measures of length and difficulty at the expense of the heritage of the design. It wouldn’t be for another 30 years that the club would have the stomach to wrestle with additional change, so contentious had been the creation of the Fazio holes.

Yet, the tide turned in 2013. While the cost would make him gasp, Ross would be thrilled with the results of the Club’s $2 million renovation that year, another indication that the club is willing to invest to attract major championship golf. All the tees, fairways and greens were re-grassed with Pure Distinction after then greenkeeper Steve Anderson had tested more than a dozen strains of bent. This tight dense turf provides optimally firm conditions for the June through September playing window. That’s crucial for a club like Inverness who desires to host the world’s best every decade or so.

This aerial captures the extensive work that was carried out in 2013 to the playing surfaces at Inverness.

Importantly, while the work was being performed, new fairway lines were established. Either the fairway lines were expanded (as seen above left where the thirteenth fairway now extends to the left bunker) or bunkers were edged into the fairways. As a result of this work and other enhancements, the collection of Ross holes at Inverness surely rank with his best in terms of appearance and playing qualities. After just a year, Anderson regularly achieves firm playing surfaces that were previously possible only with very favorable weather. The mix of shots required – from high soft floaters to low bullets – constantly rotates on the undulating playing fields.

After the work was complete in 2013, one glaring issue still remained: the Fazio holes simply didn’t fit with the Ross ones. Despite the holes all featuring the same style bunkering, the course’s reputation was permanently hobbled by their presence. Further action was required for Inverness to reclaim its exalted position as among one of Ross’s handful of finest designs. And that’s where architect Andrew Green enters the narrative. As we will read below, he boldly ventured into section of the property that Ross hadn’t, in part because the Club didn’t own the land at the time. Gone were the glaring foibles and in their place emerged holes that look like they belong and are consistent with the Golden Age design themes

Let’s examine the panoply of pleasurable holes that now constitute the Inverness Club. As you will see, its world-class holes are no longer bogged down by poor, ill-fitting ones and that makes this collection of eighteen holes formidable indeed.

Holes to Note

First hole, 400/385 yards; The golfer is introduced straightaway to Inverness’s unique topography with the golfer needing to negotiate not one but two valleys. Immediately, the theme is established for driving the ball in the fairway. If you don’t, how and where to lay-up becomes problematic much more so than at most courses where a standard punch out suffices.

A cluster of bunkers divides the first and tenth fairways. The good news is that if you find the first fairway, you likely enjoy a level stance for …

Second hole, 485/395 yards; Of the thirteen par fours only this one, its parallel cousin at eleven and the ninth play over flat land from tee to green. Despite their lackluster terrain, all three are very fine holes. A distinctive nest of bunkers handsomely enlarged by Arthur Hills in 2013 separates the second and eleventh fairways. The presence of the irregular, grassed-faced bunkers has been amplified by tree removal, part of Inverness’s ongoing tree management program. Just a decade ago, Inverness was forested, robbing people of an accurate impression of the land’s beautiful rolls. Green actually pushed Ross’s green back some sixty yards in 2017 in order to guarantee the success of the next three holes.

…from the rear, the new green that extending the hole looks, acts and plays like it belongs on this Ross course.

Third hole, 275/195 yards; In a master design stroke, Green decided to replicate much of the playing features of Ross’s old one shot eighth but he so on an entirely different piece of the property. What he extinguished was a much hated one shotter that had been installed in the late 1970s and included a pond. The notion of an artificial pond being added to a classic 1910s Ross course had been nails on the chalk board for years to traditionalists. It has been completely wiped away and indeed Green’s par 3 shots off at a 90+ degree angle from the old one. Good riddance to that chapter and welcome to one that begs for a finely gauged running approach.

As seen from the side, the third green is open in front and narrows toward the rear, making back hole locations particularly troublesome.

Fourth hole, 515/385 yards; The second most hated feature to make its way into this course after the pond at three was a creek on the outside of the old dogleg fifth. That’s right – the outside, which ruined any hope that the hole would ever feel apart of the fabric of a Golden Age course. Again, full props to Green for having the vision to find and route this tough shotter in such a manner that the once offending creek is now on the inside of this dogleg left.

Sixth hole, 465/430 yards; Is it harder to reach this monster in regulation or to two putt its exuberant green? Regardless, you get the point. Similar to the first a carry over a valley is required on the approach shot but almost certainly with a long club. One can only imagine how few members hit this green in regulation during the days of hickory. As spectacular as it is large, the putting surface features a high point front right with frightening slopes racing away left and rear. Featuring only two par fives and three par threes, Inverness’s reputation hinges on the quality of its two shot holes. By the time he has reached the fifth tee the golfer is cognizant of why that is. Jermain opined, ‘From a mashie niblick to a spoon or brassie the second shot at Inverness is the crucial test.’

The concept of covering this kind of terrain and holing out on this viciously contoured green in a mere four shots is alien to the author.

Seventh hole, 480/435 yards; An epic hole that once again follows the prior brute just as it did in Ross’s day. This pair constitutes the most difficult back-to-back two shotters on any Ross course with which the author is familiar. They are like following the fourth at Seminole with … the fourth at Seminole! In fact, information exists to suggest that par for each hole was determined daily with the one played into the wind listed as a ‘5.’ The 1931 U.S. Open program accurately summed it up: ‘A remarkable golf hole, picturesque, naturally protected, the hardest par four at Inverness, and recognized by any authority as one of the best on any course in any country.’ The author racks his brain trying to thinking of any two world class par fours of such uncompromising quality that are back to back and all he can come up with in world golf are 8-9-10 at Pebble Beach and 10-11 at Augusta National.

Can the golfer carry the brook and open up the elevated green from the right? If not, the approach is likely blind over the left mound eighty yards short of the green.

The seventh is a prime example of an architect incorporating diverse natural features. A brook threatens off the tee and a hillside for the second: what more do you want from inland golf?!

Eighth hole, 585/520 yards; The old eighth was the author’s favorite Fazio hole, which had been created by merging two short Ross two shotters that no longer made sense – nor were safe – for the modern game. Green improved upon the hole when he lessened the degree of the dogleg by pushing the green forty yards right from Fazio’s location. Any lingering sense of abruptness is now gone and like two of Ross’s holes (e.g. the first and the sixth), the golfer needs to find the short grass off the tee to seamlessly cross the valley with his second shot. It’s a fine position hole and the 9 handicapper needs to understand that the usual sloppy tactics he employs at most three shotters will meet with harsh results here.

Ninth hole, 465/345 yards; Ross courses built in different decades possess charming anachronisms. One such feature is found greenside here where dirt was pushed to create left and right mounds into which Ross cut bunkers. It’s seen at other pre-1920 Ross designs like Wannamoisett but rarely thereafter when he tended to build his green pads taller and cut the bunkers into their bases. The ninth plays along the flat border of the property and the mounds furnish the green complex its visual interest. When played from the back markers, it’s a daunting second shot to one of Inverness’s famous intermediate sized greens. This putting surface is even smaller than the course’s average of 4,360 square foot, in part because Ross built it as a green to defend a reachable par 5. In an example of how the game has evolved, the hole is nearly the same length as it was for the 1920 U.S. Open but it’s now a par 4! Out of bounds is a scant fifteen paces left and behind the none-too-big green.

The golfer is cocooned from outside intrusions everywhere at Inverness except for the approach into the ninth where various non-golf activities neighbor the green. Nonetheless, the golf is so could, it is one of the author’s favorite holes.

Tenth hole, 395/350 yards; Tee to green, the first and tenth holes occupy the same compelling terrain. Both tee balls are over the same valley to the same plateau but then the two holes suddenly become quite different by virtue of the green placements. At 2,500 square feet, the tenth’s putting surface is the smallest on the course but with enough movement to elicit a 3 putt at the absolute worst time. See the 1993 PGA playoff for details. Not only were aesthetics greatly enhanced when Hills streamlined the first and tenth tees into one huge complex but the tenth seamlessly picked up 25 yards of additional length.

While the expansive first green on the right is placed high on the far bank, Ross slotted the tiny tenth green at the base on the left.

Twelfth hole, 170/135 yards; How an architect builds a one shotter across flat land is telling. Master architects who successfully did so include George Thomas at the fifteenth at Los Angles County Club, Seth Raynor with the eighth at Camargo and Ross here. The necklace of five bunkers that hangs around the sides and front of this green obscures the putting surface from the tee. That’s worrisome because a long spine divides the green into left and right portions and life is much better if your tee ball rests on the same section as the day’s hole. It’s the only surviving Ross par three and reeks with character. Juxtaposed as it is to the unfortunate third only magnifies that ignominy.

Thirteenth hole, 515/485 yards; Hugely underrated, this 1/2 par hole is laid over scintillating topography. Maybe it doesn’t get the love it deserves because it often plays as the easiest hole relative to par during stroke play events. Such dismissive logic has never applied to the thirteenth at Augusta National, so …. why should it here?! The green rivals the seventeenth for the most brutal back to front slope on the course. Consider the stylishness and exemplarity of the four green complexes that start the inward nine and how the approach shots vary: a downhill pitch to the island tenth green, the open eleventh that is glued to the ground, the cleverly bunkered twelfth and the pushed-up thirteenth green with its wicked slopes.

Shadows mask how convoluted the landforms are in the hitting area. Getting a good strike from such an awkward lie (and potentially reaching the green in two) is the hallmark of talent.

The golfer’s lot in life greatly improves if his approach scales in two the embankment 50 yards shy of the thirteenth green.

As seen from the left side, golfers can be easily ‘de-greened’ if their first putt is a little frisky from above the hole. Interestingly, A. W. Tillinghast built this green for the 1931 US Open. It is a rare but great example of how hosting a major event actually improved a Ross design.

Fourteenth hole, 485/410 yards; Inside the clubhouse, the walls are replete with photographs of golfing greats and tournament lore. Those fortunate to play here become keenly aware of Inverness’s place in history and a hole like this that feels like a step back in time should be savored. Vive la différence, this lay of the land hole is the type no longer seen on modern venues, complete with an intermediate size green that is open across the front and at grade with the fairway. Links golf, anyone?

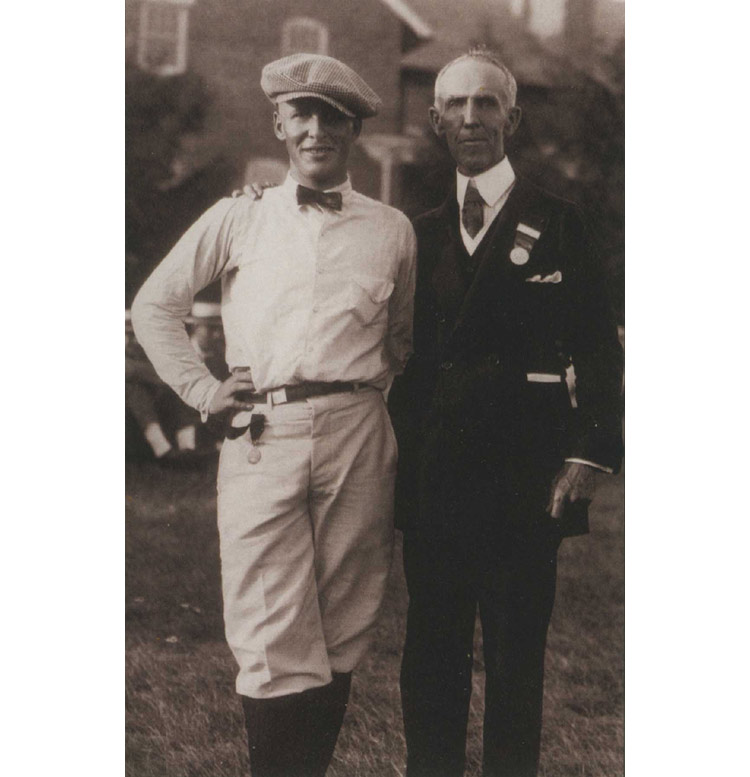

Antiquated features include this gnarly, ‘carry me or else’ 30 foot embankment off the tee. No problem for the dapper Ted Ray though!

This unique 75 yard long horseshoe bunker separates the fourteenth and fifteenth fairways. Its slender nature produces nasty lies, difficult stances and muttering golfers, who are reminded that bunkers are indeed hazardous.

Fifteenth hole, 470/415 yards; Straight drivers of the golf ball tend to enjoy a bigger advantage at Inverness than at most courses because wayward drives leave onerous recoveries over hill, dale and trench. Streams and or depressions are found 20 to 80 yards short of numerous greens including the first, fourth, fifth, seventh, tenth, fifteenth and seventeenth. Little wonder that Greg Norman threatened here in 1986 and 1993 and that the final scoreboard at the 1979 US Open included some of the game’s straightest drivers and best tacticians: Hale Irwin, Jerry Pate, Gary Player, Larry Nelson, Bill Rodgers, Tom Weiskopf, and David Graham.

The approach to the fifteenth is one of the most attractive on the course and is best enjoyed from the fairway.

Sixteenth hole, 410/395; The nature of Inverness’s mostly rectangular property is that its north/south axis is approximately twice as long as the east/west limb. As such, a slew of parallel playing corridors constitute the bulk of the routing. Yet, this is obscured by the ever-changing manner in which Ross utilized the river valleys. Here the challenge is direct: the golfer needs to get away two rifle straight shots. Like putting where no good golfer likes to be told that a putt is ‘dead straight’, one prefers ‘cutting it off that tree’ or ‘drawing off this bunker.’ They don’t exist at sixteen and that contributes to making this one of the harder fairways to hit consistently. Unless the golfer gets a clean strike on the ball as afforded from the tight fairways, he is unlikely to gain/maintain satisfactory control on his approach into this sloping green.

Note the clean entrance, the reclaimed back wings and Ross’s exquisite contours. Pity modern architects don’t build such greens.

Seventeenth hole, 475/385 yards; How holes evolve is intensely interesting. A 1931 aerial that hangs inside the professional shop shows this hole being more linear in nature. Today it bends around a handsome, steep-faced bunker that chews into the left fairway. Squeezing a tee ball between it and the far right bunker is one of the most demanding – and satisfying – tee shots on the course. Dick Wilson apparently added the island and enlarged the left greenside bunker, creating a 50 yard long monstrous yet striking hazard. In their own way, the last two holes remind the author of the finishing two at The Old Course at St. Andrews. At both courses, the penultimate hole is the longer/harder of the two and plays to a vicious green that seems ill-conceived to receive a lengthy shot. Surprisingly, the seventeenth green is under 3,500 square feet, making it the third smallest target at Inverness.

Considering its fierce slopes, a prudent leave is often just short of the seventeenth green. Long or right can leave the golfer inconsolable.

It can’t be overstated: Inverness occupies gorgeous property that has been enhanced for more than a century.

Eighteenth hole, 360/300 yards; The Home hole is memorable for a host of reasons that include it being the only hole to play in a valley as opposed to across one. A range of options exists off the tee, depending on what kind of club you are most comfortable with hitting to the green. If the hole is left, the golfer tries to stay right off the tee and vice versa when the hole is right. Head Golf Professional Derek Brody considers the most difficult hole location to be back right. Miss it right, and you are in the trough, a wonderfully unique steep walled depression. Placed beneath the clubhouse windows and porch, this feature makes for great theater. The ever-hopeful golfer conjures up (generally only in his own mind though!) some kind of a miraculous recovery while the members look on with all-knowing pity. The front left bunker from which Bob Tway holed his miracle shot may be more famous but the green’s tilt and trough are the star features. This sub-400 yard closer and standout Ross green complex create a perfect conclusion to a singular experience.

This zoomed view shows the playing angles. For right hole location, Brody prefers to position his tee ball near the far left bunker.

This view from behind hints at the green’s severe cant. Any approach that just misses right finds the cruel two foot trench that has broken so many fine men.

Though the Club has altered the course over the decades, one tenet that hasn’t budged is the club’s insistence that golf be a walking sport. As well as anyone in America, Inverness supports the Chick Evans Caddie Scholarship Program. They have upwards of 225 locals at the ready June through August enabling a one caddie to one bag ratio.

History at Inverness is entwined with that of American golf and the ascendency of the golf professional. Golf professionals were first invited into the clubhouse here and gifted the club its iconic grandfather clock in 1921. The inscription captures the essence of the people and the Club:

God measures men by what they are

Not what they in wealth possess

That vibrant message chimes afar

The Voice of Inverness.

The actions of the current membership indicate that Inverness continues to embrace major championship golf and is able to strike a balance between tradition and the modern game. Adjectives like ‘tree-lined’, ‘narrow’, and ‘testing’ belong in decades past. Today’s golfer is looking for something more exhilarating. He wants to be tested mentally as well as physically; he needs options to mull over and playing angles to consider. Recent events at Inverness have had the first and tenth tees reversed so that creative challenges are brought to bear on those two holes. In addition, a popular spot for the eighteenth tee is near the 300 yard mark where it promotes a blend of heroic and tragic results. Inverness is once again on the move, and for all the right reasons.

In 1920 S.P. Jermain proclaimed: ‘Inverness has today many acres of most beautiful, deep and velvety turf, a delight to the eye and a joy to tread. Truly can it be emphasized that it was “a golf course—predestined.” Its pioneers deeply realized that here could be built a truly great course and withal one of much natural beauty, for indeed the maximum happiness in golf requires both.’ The current custodians in Toledo have insured that these words resonate loud and clear.

The author gratefully acknowledges the use of the Club’s and member Dave Ukrop’s photographs.

![The Park, West Palm (Lit 9) [2023]](https://golfclubatlas.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/IMG_7092-2-scaled-500x383.jpg)